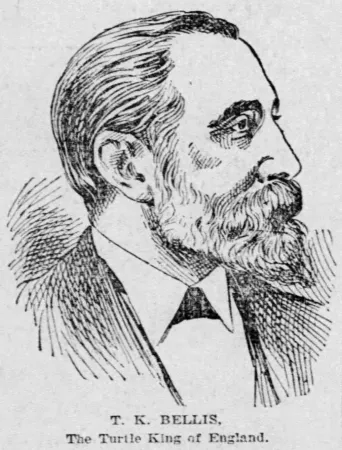

Ransacking nature and building up a fortune by satisfying the cravings of a selfish elite; Or, How an industry dominated by T.K. Bellis Turtle Company Limited of London, England, nearly obliterated a true marvel of the sea, Part 1

I have never tasted turtle soup, my reading friend, and do not plan to. Ever. Such a sentence may seem like a strange introduction to this issue of our all encompassing blog / bulletin / thingee but there is method behind the madness. Speaking (typing?) of madness, you may wish to note that this article will deal before long with the greedy madness behind the monstrous evil known as the Atlantic slave trade, but we are not there yet.

For a few decades now, sea turtles have been some of the most beloved sea creatures on Earth. (Hello, EG and EP!). As you know, these elegant and peaceful reptiles have been roaming the oceans for quite some time before Homo sapiens came along and began to f*ck things up. Yea. The fossils of the oldest known genera, Desmatochelys, were found in 120 000 000 year old rocks, and the truth is that these 2 metre (6 feet 6 inches) long animals were probably not the very first sea turtles. After all, the oldest known turtle, Proganochelys, ambled along on terra firma about 210 000 000 years ago.

And if you think Desmatochelys was big, yours truly has news for you. About 75 to 80 000 000 years ago, had you swum in the Western Interior Seaway, between Laramidia and Appalachia, in what is now North America, you might have come across the odd Archelon, a chelonian which might have reached a tip of nose to tip of tail length of up to 4.6 metre (15 feet) and weighed up to 3 200 kilogrammes (7 000 pounds). I kid you not.

Incidentally, any male Homo sapiens dumb enough to entertain the idea of turning an Archelon into soup would have realised pretty darn quick that he had bitten off more than he could chew. Indeed, that hapless twit might have become a tasty lunch.

Mind you, that twit might also have come across sharks measuring up to 8 metres (26 feet), not to mention short-necked plesiosaurs (pliosaurs) as well as mosasaurs, multi-tonne carnivorous reptilian beasties which could reach length of up to 18 metres (59 feet). Beasties which could have swallowed him whole without so much as a hello, or goodbye, but I digress.

What can I say (type?)? I really like to read about Earth’s fauna in ancient times, as you might have guessed by now, but back to our tale of woe – and T.K. Bellis Turtle Company Limited of London, England.

The founder of that firm, Thomas Kerrison Bellis, was born in England, in February 1841. He moved to London around 1856 and found work with merchants whose business interests were in the West Indies / Caribbean. Bellis presumably first heard about the sea turtle trade while working for them. Whether or not he remained with that firm or moved to other firms whose business interests were in the West Indies was / is unclear, at least to yours truly.

In any event, Bellis came to realise that the way the sea turtle trade was organised was quite inefficient. Indeed, again, that trade had been quite inefficient pretty much since day one. That day seemingly dawned at some point in the 17th century.

Sea turtles were really common in the Caribbean at that time and that is where the crews of European ships learned from the indigenous peoples of the region that the meat of these animals was quite edible. The ability of sea turtles to survive for quite long periods of time in captivity made them an ideal source of fresh meat during oceanic voyages. That discovery was in all likelihood made well before the 17th century, actually, if only because these indigenous people had been almost obliterated by the Spaniards during the 16th century.

The sea turtles in question were primarily green sea turtles, peaceful vegetarian sea creatures, omnivorous during their youth, which often achieve a length of 1.5 or so metre (5 or so feet) and a weight of up to 190 kilogrammes (420 pounds) – if humans did not capture them first and prematurely end a life which could last up to 90 years.

As sugar production took off in the 17th century, mainly on Caribbean islands controlled by England and France, green sea turtles were an easily accessible / cheap source of meat for the countless enslaved Africans who toiled endlessly, and died, in those hellholes.

A potentially controversial comment if I may. Salted cod originating from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland was another easily accessible and cheap source of meat.

As their slaves were exploited onto death, the wealthier and wealthier b*st*rds who owned them gradually discovered a taste for turtle soup. Slurped at their tables as a sign of their opulence, that dish soon made its way across the Atlantic Ocean, where it retained its high status.

This being said (typed?), no one seems to know when or where turtle soup was first served in England and Europe. According to some, the time and place were 1711 and London. According to others who do not have a year to propose, the place was Bristol, England, one of the oldest slave trade harbours in that country. King George II, born Georg August of house Hanover, reportedly enjoyed some turtle meat with his family as early as 1728.

The first known written instructions detailing how to cook (stew? roast? boil? bake? etc.) a green sea turtle might have been made available to the multitude in 1732, I think, by an English naturalist / botanist, Richard Bradley, in his The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director in the Management of a House, and the Delights and Profits of a Farm.

What was it about turtle soup that fascinated the English so much, you ask, my reading friend? A good question. I wish I knew. The Spaniards and Portuguese certainly had access to turtle meat but were not too thrilled by it. The French showed some interest but the best hunting spots were under English control. Who knows, the world renowned characteristics of English cooking might have played a part in activating that fascination.

This being said (typed?), at least one set of instructions detailing how to prepare a sea turtle was penned around the early 18th century by a botanist / coloniser / explorer / landowner / soldier / writer, Jean-Baptiste Labat. Some light can be shone on the character of that wealthy slave-owning French Dominican missionary, yep, a slave owning Roman Catholic missionary, by stating that, in 2023, 285 years after the death of that ineffable individual, in Martinican Creole, the term pèrlaba, in English think fatherlaba, apparently described an evil spirit. Wow…

It was in the late 1740s, or the mid 1750s, however, that turtle soup per se slowly entered into legend, with the inclusion of a recipe in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, one of the best-selling recipe books of the 18th century, written by famous English cookery writer Hannah Glasse, born Allgood.

Turtle meat seemingly acquired that same status as a result of the publicity surrounding a couple of 1754 banquets organised in London by the First Lord of the Admiralty, the political head of the Royal Navy, Baron / Lord Anson, born George Anson, one of them offered to members of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge.

Mind you, by then, Anson had already if indirectly changed the way the English elite saw sea turtles. You see, my reading friend, A Voyage round the World, In the Years 1740-1744, the very well received first hand account of a circumnavigation of the globe headed by then Commodore Anson, published in 1748 by his official chaplain, Richard Walter, waxed almost lyrical about the meat of sea turtles, the crews’ sole source of nourishment during a period of 4 or so months. It was assuredly better than the meat of penguins or iguanas.

And no, the voyage in question was not a journey of exploration. That 1740 mission had for objective an assault against Spanish possessions and ships in the Americas. By the time Howe returned home, in 1744, with 1 of the 6 Royal Navy ships he had left with, 90 % of the men he had started his mission with were dead, mainly from scurvy. The hold of his ship was, however, filled with Spanish silver coins. Anson’s share of the loot turned him into a very rich and influential man. Heck, he was a national hero. What the Spanish government thought of Anson cannot be repeated here.

And yes, the Avro Anson coastal patrol / advanced training aircraft operated by the Royal Air Force and more than 25 other air forces around the globe, including the Royal Canadian Air Force, was named after Baron Anson. The justification for that otherwise unnecessary statement is the fact that the breathtaking collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes an Anson.

You did not think that the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, a glorious institution if there was ever one, would be mentioned in this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, now did you? As was pointed out in the past, given that there is most certainly a will on my part to mention that incomparable museal institution as often as (in)humanly possible, you can bet your knickers that I will do my very best to find a way to do it, but back to our story.

By the second half of the 18th century, the turtle soup craze had reached such a height that some / many ships were fitted with tubs containing seawater in order to “improve” the comfort of the sea turtles, and reduce the number of fatalities, thus increasing the profits of the merchants involved in that trade. Indeed, it has been suggested that several ships were actually built for the turtle trade.

As you may well imagine, not everyone who wanted to keep up with the Joneses could afford to serve turtle soup. Thus was born, no later than the early 1750s, the dish known as mock turtle soup. The ineffable main ingredient of some / many versions of that English concoction shall remain nameless. Look it up online. If you dare.

Let us be blunt, the sea turtle had snob appeal. That very appeal led a number of British satirists to associate the consumption of sea turtle meat with cupidity, gluttony and an absence of self control. Some even linked that consumption with the savagery of slavery, the peculiar institution which made more than a few members of the British / English merchant class obscenely wealthy – and millions of African slaves obscenely dead.

As a white male Homo sapiens, I can only wonder to what extent the foundations of the current wealth of Western European and North American countries were built on the exploitation of people who were just as human as me, but back to our story.

As fascinated as many Britons were by turtle soup, it was not the British national dish, however, contrary to what wrote one of the first food reviewers and restaurant critics on planet Earth, Frenchman Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de la Reynière, in the early 19th century, quite possibly in one of the annual editions, published between 1803 and 1812, of a popular and witty if controversial and scathing work, L’Almanach des gourmands. Worse still, Grimod de la Reynière might, I repeat might, have confused turtle soup with mock turtle soup. Goodness gracious / bonté gracieuse.

Incidentally, would you believe that, no later than the early 1860s, at least one English firm began to produce produced canned mock turtle soup?

In turn, at least one American meat packing firm began to produce canned sea turtle products around that time. And yes, there were also a lot of people among the American elite who consumed sea turtle products, especially turtle soup, and this right into the Gilded Age / Belle Époque and beyond.

Various types of British canned and bottled sea turtle (and mock sea turtle?) products were displayed at the International Fisheries Exhibition and International Health Exhibition held in London in 1883 and 1884. Around that time, at least one of the firms involved in that production actually warned its customers: “Beware of imitations.”

In the United States, food processing giant H.J. Heinz Company Limited produced canned mock turtle soup no later than the 1930s. The nature of the main ingredient of that particular product has so far escaped me, but back to the Gilded Age / Belle Époque, a period which was neither gilded nor belle for the huge majority of people on planet Earth.

Before we get there, yours truly would be remiss if I did not point out that the Mock Turtle was / is a melancholic character in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the world famous 1865 novel by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, an English author, mathematician and poet better known by his pen name, Lewis Carroll.

As the years turned into decades, countless green sea turtles captured in the Caribbean crossed the Atlantic Ocean to feed the wealthy and mighty elites of the United Kingdom and elsewhere. A significant percentage (up to 1 in 4, if not more?) of these animals died during the trip. And if you think that was bad, please note that, on one occasion, in the fall of 1903, no less than 120 of the 150 turtles carried on one ship died.

The human predation mentioned in a previous paragraph had an all too familiar consequence: populations of green sea turtles plummeted. That plummeting had an equally familiar consequence, courtesy of the law of supply and demand so familiar to the regulars of London’s business district: the value of a live green sea turtle skyrocketed. No later than 1861, the first year of the 1860s you will remember, no soup available on the posh tables of London, either private or public, cost more than turtle soup.

It was / is a safe bet that green sea turtle hunters only got a tiny fraction of the moolah that British importers raked in with shovels. Ahh, capitalism. Is it not wonderful?

Mind you, the fact that, as early as the 1760s, turtle soup became a standard feature in the huge annual banquets hosted by the Right Honourable Lord Mayor of London since the 13th century, and remained so for many decades, at least until the end of the 1930s in fact, certainly contributed to the plummeting of green sea turtle populations.

Incidentally, the mayor in question was not / is not the mayor of the capital of the United Kingdom, a position which came into physical existence in May… 2000. Nay. The Right Honourable Lord Mayor of London was / is the mayor of the City of London, a small area centered upon the business district of the English / British metropolis, but back to our topic. Again. Sorry.

And yes, there were many people who thought that the food served in London’s public establishments was badly cooked. And do not get them started on the quality of the service, or lack thereof.

Before I forget, some establishments whose sea turtle meals were particularly popular with London muckymucks, George Painter’s Ship and Turtle tavern for example, had tubs where these animals were kept alive to satisfy the needs of wealthy Homo sapiens who were feeling peckish. Mind you, Londoners who had the financial means to do so could buy a turtle from people like Painter, and have it, well, err, processed.

Speaking (typing?) of public establishments, the earliest local reference to turtle soup that your truly could find in Canadian newspapers was in October 1832 and…

Yes, I do realise that Canada did not exist in 1832. There were, however, several British colonies / territories in what was commonly called British North America, namely the British Arctic Territories, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Rupert’s Land. The Columbia Department / Oregon Country, on the other hand, was a disputed piece of land on the west coast of North America that the United Kingdom “shared” with the United States. Can we go back to 1832 now, my nitpicking reading friend? Thank you.

The earliest local reference to turtle soup that your truly could find in Canadian newspapers was in October 1832. That month, in the largest city of the Province of Canada, Montréal, a hotel owner by the name of Patrick Swords offered that dish to whoever could pay for a bowl. The one green sea turtle killed for the occasion had been obtained “at considerable expense and trouble” in New York City, New York.

Incidentally, Sword’s hotel seemingly became, in January 1834, the first building lit, if only in part, by gas in what was then the Canada East portion of the Province of Canada and what is now, in 2023, the province of Québec. The gas in question was of course coal gas / lighting gas / town gas. The installation of all the required plumbing in the bar, confectionary and inner reception room was made possible by the close cooperation of Montreal Water Works Company.

A brief aeronautical digression if I may. In July 1821, the English aeronaut / balloonist Charles Green made the first flight ever made in a gas balloon whose envelope was filled with coal gas. That lighter than air gas, although rather less efficient than hydrogen, was more readily available and significantly cheaper. And yes, it too was flammable. From 1821 onward, coal gas was widely used by aeronauts / balloonists on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. It is well worth noting that Green was / is one of the most famous aeronauts of the 19th century.

You did not think that the Canada Aviation and Space Museum would be mentioned a second time in this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, now did you? You will of course remember my intention to mention that incomparable museal institution as often as (in)humanly possible. Consider this a confirmation of that statement. End of digression.

And end of the first part of this fascinating article about T.K. Bellis Turtle, the British leader of an industry which nearly obliterated a true marvel of the sea.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)