Come on, PB, light my fire. Try to set the ice on fire: A peek at the American firm Woolery Machine Company and some of its ideas and products

Hello there, my reading friend. Given the less than balmy weather in a certain northern corner of the northern hemisphere of planet Earth, yours truly thought that a topic like the one on offer today, in this edition of our heart warming blog / bulletin / thingee, would be most appropriate indeed.

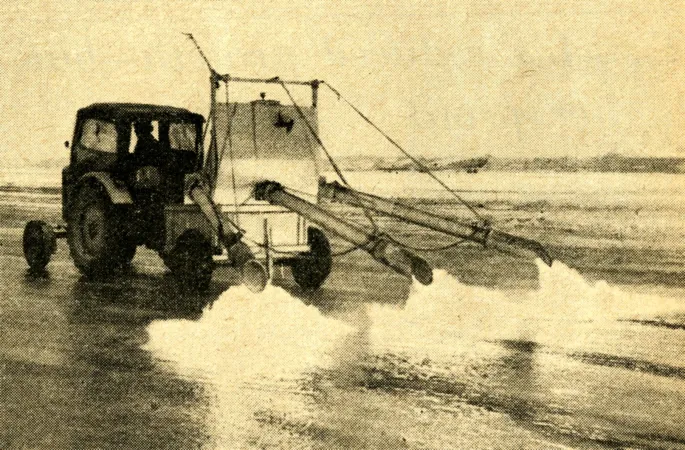

Let us begin with a quote, which consists of the brief text which accompanied the photograph above.

At Cologne-Wahn Airport an American-made ‘flame-throwing’ device has been used to free runway surfaces of ice before sanding and grinding began. – Designed by the Woolery Machine Co. of Minneapolis, it uses some [500 litres] 110 Imp. gal [132 American gallons] of diesel fuel per hour.

Fascinating, is it not? You will of course have read the two-part Ingenium Channel article put online in April 2018 which examined the use of jet engines to remove snow from airport runways and railroad tracks. And yes, there will be a test.

You will no doubt be delighted to learn (read?) that the first test in an airport of the device developed by the Woolery Machine Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota, was held no later than February 1949, at Wold-Chamberlain Field, the current Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport in… Fort Snelling, Minnesota.

Aircraft and ice do not mix well, and this either in the air or the ground. Sand spread on icy runways and / or taxiways does not necessarily work as well as sand spread on icy roads and sidewalks. Back in 1949, the air blasted by the ginormous propellers of airliners blew off that sand soon after it was spread. In any event, said sand rarely embedded itself in the ice on the runways or taxiways.

Some airport authorities tried to heat the sand before it got spread but that did not work too well either, as the individual grains of sand had a chance to cool down between the heating and spreading.

In early 1949, faced with up to 5 centimetres (2 inches) of ice on its site, the management of Wold-Chamberlain Field decided to try something new. It contacted a well known local firm, Woolery Machine Company of Minneapolis, which had a piece of gear of great potential.

Perhaps a tad surprised, or not, the firm agreed to help. Before long, one of its Model PBs was on site. It was quite the sight. After all, the trio of burners of that device were mounted side by side and covered a 4.6 metres (15 feet) wide area. The quite spectacular flames which came out of them had a temperature of about 1 150 degrees Celsius (about 2 100 degrees Fahrenheit).

Acting on suggestions made by someone, the airport authorities tried 2 de-icing methods:

- The driver of the tractor which pulled the Model PB drove over an icy runway to melt the ice. The driver of a sander drove behind him and spread sand on the wet ice, which froze back, locking in the sand.

- The driver of a sander drove over an icy runway and spread sand over it. The driver of the tractor which pulled the Model PB drove behind him, heating the sand which literally fused within the ice.

Door number 2 proved to be the better option. Within 2 hours, a 1 830 metre (6 000 feet) long and 27.5 metre (90 feet) wide runway was ready for action, providing fine braking conditions for both takeoff and landing. Pilots were delighted. So was the airport’s management.

Incidentally, the second option allowed the driver of the sander to spread his sand faster, and this without having to keep an eye of the Model PB and the rather intimidating / dangerous flames shooting out of it.

The operation had required about 380 litres (about 85 Imperial gallons / 100 American gallons) of fuel oil and about 22 675 kilogrammes (50 000 pounds) of sand. A quick calculation revealed that each square metre of runway received about 450 grammes of sand. In Imperial terms, each square foot of runway received about 1.5 ounce of sand.

At US $ 20 an hour, which corresponds to about $ 325 in 2023 Canadian currency, the Model PB was not exactly cheap but it worked. Indeed, the sand stayed put until the ice on the runway disappeared.

What was this wondrous device, you ask, my curious reading friend? Well, it was a Woolery Model PB weed burner. Yes, yes, a weed burner. Actually, it occurred to me that you might want to see that piece of gear. And here it is…

The Woolery Model PB weed burner used to melt the ice on at least one runway at Wold-Chamberlain Field, Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Anon., “Air Transport – Weed Burner ‘Sands’ Runway Ice.” Aviation Week, 14 February 1949, 35.

You will of course have noted, my smart reading friend, the similarities between the 1949 Woolery device and its 1963 counterpart, shown in the photograph at the beginning of this scintillating issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

What burns me, no pun intended, well maybe a little, is that I cannot find a single article on the airport work done by devices produced by Woolery Machine between 1949 and 1963.

The fact that the firm was mentioned almost 15 years after its initial experiment and in a British weekly magazine of all places, namely The Aeroplane and Commercial Aviation News, hinted at some work in more than one place. Especially since the article in said British weekly magazine stated that a Woolery device was seemingly in regular use at Cologne-Wahn or Köln-Wahn airport, in West Germany, in 1963, an airport which serviced both Cologne / Köln and the city of Bonn, which happened to be the capital of West Germany. And you have a question.

Who on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth needed a weed burner the size of a Model PB in 1949, you ask? Why, a railroad company of course. And hear lies a tale. Now, do not be a cry baby. It is only a brief tale. And afterward, there will be candy, cake, balloons.

Just kidding.

A gentleman by the name of Horace E. Woolery made his appearance in May 1911, in a Norwegian American weekly newspaper. I kid you not. Decorah-Posten / Decorah-Posten og Ved Arnen of Decorah, Iowa, was published between 1874 and 1972. Aimed at Norwegian Americans, that publication eventually became the most successful Norwegian language newspaper outside Norway, but back to our story, and 1911.

By that time, Woolery had, it seemed, just obtained a patent for an internal combustion engine. As far as yours truly can tell, Woolery was born around 1875. In 1911, he lived in Fairmont, Minnesota. At some point before or after that date, Woolery founded a small machine shop and foundry, quite possibly / likely in Fairmont. Realising that his firm had grown as much as it could in that small city, Woolery moved to Minneapolis. Using all of his meagre capital, he acquired a small workshop and got to work.

Mind you, another version of the story had Woolery join the staff of Fairmont Machine Company of… Fairmont at some point around 1908-09 – and remain so employed until at least 1914. Indeed, two American patents bearing the name of Woolery as inventor were in fact assigned to Fairmont Machine.

You see, back in 1907 or so, a small machine shop located in Fairmont had begun to produce a small internal combustion engine which could be used in a variety of venues. That business was incorporated as Fairmont Machine in 1909. That very year saw the first installation of its engine on a number of trolleys / trikes / track-maintenance cars / speeders / section cars / railway motor cars / railroad speeders / quads / putt-putts / jiggers / inspection cars / draisines / crew cars, in other words small powered railcars used by track inspectors and work crews to move about.

Fairmont Machine became Fairmont Gas Engine and Railway Motor Car Company in 1915. Renamed Fairmont Railway Motors Incorporated in 1923, the firm became a North American leader in the speeder industry. Would you believe that it set up a Canadian subsidiary, Fairmont Railway Motors Limited, in Toronto, Ontario, in October 1929? But I digress. Sorry.

In any event, Woolery founded Woolery Machine no later than 1916. Indeed, the presumably founded that firm some time before that date, and… How can yours truly make such a bold statement, you ask, my reading friend? Well, you see, Woolery Machine put out an illustrated (photograph) advertisement in March 1916, in at least one newspaper, for its (brand new?) speeder.

The internal combustion engine of that vehicle was said to be “the result of many years’ careful study and successful experience in motor car construction.” That statement leads yours truly to wonder if said engine was derived from the one patented in 1911. As well, one has to wonder if Woolery was involved in some way or other in automobile manufacturing. And yes, there were a few more lor less putative automobile manufacturers in Minneapolis before the onset of the First World War, in 1914.

Incidentally, the small engine of the Woolery speeder could be sold separately for installation on a human-powered draisine / handcar / jigger / kalamazoo / pump trolley / pump car / push-trolley / rail push trolley / velocipede. Liberated from having to propel their heavy vehicle, an exhausting chore if there was one, railroad company workers arrived where they were needed as fresh as daisies and ready for work.

As you may well imagine, speeders gradually replaced human-powered draisines in railroads all over North America, and beyond.

And yes, a draisine was one of the main protagonists in the 1926 American silent action / adventure / comedy silent film The General, which starred the immortal American actor and filmmaker Joseph Frank “Buster” Keaton. That film, one of the greatest American films ever made, was inspired by an event which had occurred in April 1862, during the American Civil War. Keaton’s character, Johnnie Gray, was a train engineer on the wrong side in that conflict, the Confederate States of America.

By the way, did you know that Keaton starred in the 1965 National Film Board (NFB) silent, yes, yes, silent, film The Railrodder? His character traveled from Nova Scotia all the way to British Columbia, on a speeder. As that 24 minute colour movie was filmed, the NFB produced a 55 minute black and white documentary, Buster Keaton Rides Again, but I digress. And no, I am not sorry. Keaton was / is / will continue to be be one of the greatest American actors and filmmakers in history.

And yes, you are correct my reading friend, the NFB was mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2018, but back to our story. You are the one digressing this time around.

To quote the nameless antihero V in the popular if unrewarded 2005 dystopian political action film V for Vendetta, my turn. It has been suggested that the Belgian Georges Prosper Remi, a giant of 20th century bande dessinée known as Hergé, got the idea of having his young hero Tintin travel in a draisine after seeing The General in a movie theatre in Brussels, Belgium.

You will of course remember that, having missed the train to Moscow, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Tintin set off in pursuit with a draisine whose lever gave up the ghost at some point after being frantically operated. As he pondered how to catch up with his train, our young hero saw a pile of scrap metal. Having miraculously found an automobile engine therein, Tintin mounted it on the draisine. Snowy, his faithful and, as it turned out, unusually long living canine companion, having just as miraculously found some gasoline, the dynamic duo was soon back on its way.

What was the name and year of publication of the story in question, my reading friend? That virulently anti-communist story was initially published in Le Petit Vingtième, a weekly supplement of a Catholic and deeply conservative Belgian daily newspaper, Le Vingtième Siècle, aimed at young humans, and this from January 1929 to May 1930. It was published as an album entitled Les Aventures de Tintin reporter du “Petit Vingtième” au pays des Soviets around September 1930, you say? Very good, my tintinophile reading friend!

You will of course remember… Err, please, go ahead and speak. Hergé was mentioned in several / many issues of our epoch making blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since July 2018, you say? I stand in awe of your knowledge, my reading friend. Now let us move on.

By April 1917, Woolery Machine was advertising its internal combustion engine, “Steady as a steam [engine]; quiet as a sewing machine,” for use in a variety of venues.

To answer the question that will inevitably begin to bounce in your noggin, no, Woolery Machine did not invent the speeder. Daimler Motor Company, the American subsidiary of the pioneering German firm Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, had put one of its gasoline engines on a human-powered draisine as early as 1896. And that vehicle may not have been the first either.

Stating that something, or someone, was / is the first, last or only example of its kind is a bit of a fool’s game, if you ask me. It is all but guaranteed that someone will come up with information that will deflate such a statement. A weasel expression like “one of the” is a lot safer. Just sayin’, but back to our story.

And yes, yours truly has made more than a few statements of the type I have just decried. Does that make me a fool? You tell me.

As time went by, Woolery Machine seemingly sold engines and / or speeders to most of the railway firms operating in the Midwest and west west of the United States. It also sold engines and / or speeders to some railway firms operating in Mexico and Canada. Would you believe that Woolery Machine sold some speeders to a Japanese railway firm?

Just like Fairmont Railway Motors, Woolery Machine might, I repeat might, have been one of the biggest players in the speeder industry from the 1920s onward.

In 1926, Woolery Machine worked on a machine which used fire, I think, to melt snow on city streets and along railroad tracks. Whether or not that machine was put in production is unclear. Woolery Machine also developed an oil burner, a railroad track bolt tightener and several other products. The firm, it seemed, did not want to be a one trick pony.

Incidentally, the Woolery Bullet automatic (and electric?) oil burner sold for US $ 245 to US $ 285 as of 1934, which corresponds to about $ 7 400 to $ 8 600 in 2023 Canadian currency. Hundreds of these devices could be found in houses (and small businesses?) in Minneapolis, Minnesota and elsewhere.

The National Housing Act of 1934, “an act to encourage improvement in housing standards and conditions, to provide a system of mutual mortgage insurance, and for other purposes,” an act put forward by the administration headed by Franklin Delano “F.D.R.” Roosevelt, played a crucial role in that regard. Indeed, Woolery Machine had to increase its payroll by 80 % in 1934 to keep up with demand, but let us now go back in time.

And yes, Roosevelt was mentioned in May 2019, March 2021 and November 2021 issues of our awe inspiring blog / bulletin / thingee.

By late 1926, Woolery Machine had developed a brand new product and you know which one of course, my reading friend… You do not, now do you? Sigh…

In late June, or very, very early July 1927, Woolery Machine demonstrated a device which used fire to destroy weeds and their seeds along railway tracks, in other words a weed burner. Tadaa. That demonstration took place in the stock or freight yard operated by Minnesota Transfer Railway Company, in Minneapolis or St. Paul, Minnesota. It was witnessed by representatives of several railway firms as well as by representatives of the following organisations:

- the College of Agriculture of the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities,

- the Department of Highways of Minnesota, and

- the United States Department of Agriculture.

The newspaper report indicated that additional models of the device were under development, respectively to destroy weeds and their seeds along roads or insects and weeds on farms.

By the time the roaring 20s came to an end, and the dirty 30s burst upon the scene, Woolery Machine was offering at least three different types of weed burners. The Midget Octopus had a pair of burners mounted side by side which provided a wall of fire 3.05 metres (10 feet) wide. By comparison, the Big Octopus had a quintet of burners which provided a 7.6 metre (25 feet) wall of fire. Mind you, its arms could be swung out to cover a 10.7 metre (35 feet) wide area. That device allegedly included a 5 300 litre (1 165 Imperial gallons / 1 400 American gallons) tank of fuel.

And yes, yours truly has a feeling that the third type of weed burners had a trio of burners. Whether or not that device was referred as an Octopus was / is unclear.

Although effective, the typical Woolery weed burner was not exactly cheap. In 1934, the Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia Railway Company paid a cool (hot?) US $ 2 000 for a three-burner device – one of the first if not the first one to be found in the southern United States from the looks of it, it was stated. That US $ 2 000 corresponds to approximately $ 60 500 in 2023 Canadian currency.

And yes, railroad firms had to exercise caution when using their weed burners. Operating such devices on a track passing through grassland, or near farmland, in the middle of a drought, was not a good idea, for example.

Oddly enough, or perhaps not so oddly, the well known American journalist and novelist Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Norris, Junior, had published the novel The Octopus: A Story of California in 1901. The book in question described the conflict between some California wheat growers and a railway company, the fictional Pacific and Southwestern Railroad, the octopus of the title. It was directly inspired by a May 1880 shootout on a California farm, the Mussel Slough Tragedy, which had left 7 people dead, 5 of them settlers. The railroad firm involved in that tragedy was the very real and very powerful Southern Pacific Railroad Company.

It should be noted that, like many successful Americans of his time, Norris believed in the superiority of the “Anglo-Saxon race.” He disliked / despised African Americans, Asian Americans, Indigenous Americans, non Anglo-Saxon European immigrants – and the working poor, but enough said (typed?) about that nogoodnik.

By 1936, Woolery Machine was producing a combined furnace and air conditioning system. In August 1938, the firm launched the improved and very successful Woolery 100. By 1939, that device could burn either oil or gas.

In June of that year, Woolery boarded an airliner operated by Northwest Airlines Incorporated. The president and treasurer of Woolery Machine was beginning a 20 000 kilometre (12 500 miles) trip to Argentina in the hope of signing some contracts. He seemingly remained in South America for a full month.

Yours truly has a feeling that the airliner boarded by Woolery, at the aforementioned Wold-Chamberlain Field, was a Lockheed Model 10 Electra, a type of aircraft represented in the stupendous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario.

You did not think that this glorious institution would be mentioned in this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, now did you? As was pointed out last week, given that there is most certainly a will on my part to mention that incomparable museal institution as often as (in)humanly possible, you can be sure that I will do my very best to find a way to do it, but back to our story.

Sadly, no information whatsoever has surfaced regarding the role played by Woolery Machine during the Second World War. This being said (typed?), it is likely that production of the weed burners with 1 to 5 burners continued throughout the conflict, and into the 1950s. By then, more than 125 American and foreign railroad firms were using various types of Woolery equipment, from speeders to weed burners – and more.

A far sadder piece of news was the fact that the founder of Woolery Machine died in April 1945, in St. Paul, Minnesota, at age 70. He was succeeded, either at that time or later, by his son, Lloyd Earl Woolery.

By 1946, Woolery Machine had developed a “six-row flame potato vine killer.” As far as yours truly can tell, the potato vine in question was not / is not some sort ornamental plant related to the potato and tomato plants. Nay. The device in question was used to burn immature potato plants so that harvesting could proceed when it was most convenient.

Mind you, the Woolery PB weed burner used at Wold-Chamberlain Field in 1949 could also be used to burn potato vines. Advertisements to that effect were put in several issues of the monthly magazine American Potato Journal in the early postwar years, for example.

In 1962, Woolery Machine began to produce a brand new product. That story had begun a tad earlier when the founding president of Countryman-Klang Film Productions Incorporated of Minneapolis was asked to shoot a television commercial. The client required that a mountain waterfall be filmed from above and that the camera slowly pan downstream to show the product, safely perched on a rock. Building a miniature waterfall and stream was no problem for Thomas C. “Tom” Countryman. Renting a large camera dolly and figuring out a way to shoot the scene proved to be a tad complicated, however. There had to be a better way.

Countryman thus set out to design a small, simple and manageable (Hello, EG and EP!) hydraulically-operated camera dolly that even a small firm like his could use. The Porta-Dolly, as the device became known, created such a stir within the film industry that it was soon put in (limited?) production by, you guessed it, Woolery Machine. You see, Countryman’s dolly could be of use to both large movie studios or small television stations. Besides being small, simple and manageable (Hello again!), it was adaptable, economical, light and versatile. Oh yes, and it cost only US $ 1 187, which corresponds to approximately $ 16 000 in 2023 Canadian currency.

The Porta-Dolly was first shown in public in October 1962. By late December, 15 or so had been sold. A version fitted with an electric motor for use in outdoor shoots was under development at the time. Pretty good, eh. What was not quite as good, at least for Woolery Machine, was that Countryman-Klang Film Productions soon chose to produce the Porta-Dolly itself.

By 1964 at the latest, the Porta-Dolly could be bought in 5 locations in the United States. It could also be purchased in London, England, and in Toronto, at a distributor of photographic, motion picture and electronic equipment, Alex L. Clark Limited, and…

Why are you smirking, my easily amused reading friend? Oh, I see. To answer the question which is currently bouncing in your slightly naughty noggin, the term Porta-Dolly was apparently not, I repeat not, inspired by the term porta-potty, which has been used for quite some time to describe a portable toilet / mobile toilet / thunderbox / portaloo / porta-john / port-o-john / mobile non-sewer-connected toilet cabin. That last expression is an official one, yes, yes, official, adopted in March 2012 by the European Union. I could provide you with a Web reference if you do not believe me.

Incidentally, the Porra-Potti hand-carried portable toilet was introduced in 1968 by Thetford Corporation, an American maker of portable toilets as well as toilets used on recreational vehicles, not to mention refrigerators used on such vehicles, but I digress.

Woolery Machine was still in business as the 1970s began. By then, however, its weed control methods had undergone some change. Its devices scalded the pesky plants rather than incinerate them. Mind you, the firm also produced devices which were more versatile, being able to scald weeds, heat railroad tracks and melt snow or ice.

Woolery Machine went out of business at some point later on. Yours truly wishes he could tell you more. Sorry.

Yours truly can, however, bring to your attention the prototype of a runway snow melting device developed in the 1970s by a small Canadian firm, Trans-Continental Purification Research and Development Limited of North Bay, Ontario. Transport Canada conducted chemical de-icing, runway snow removal and traction measurements trials with said prototype, which might have been nicknamed Little Albert.

Incidentally, the automobile used for the traction measurements trials was a former Royal Canadian Mounted Police police cruiser modified by the good people of the Langley Research Center of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, a world famous administration mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018.

And yes, as was the case with Woolery Machine, the original plan of the firm’s founder, Albert Z. Morin, was not to develop a runway snow melting device. Nay. The founding president of a small and versatile firm (digging and trenching), A.Z. Morin Construction Company Limited, also based in North Bay and active since at least 1961, developed a self-propelled and self-loaded snow melting machine for use on city streets. At least one example of the Jet Melt was under test in the fall of 1971, and…

You know what, my reading friend, the saga of the Jet Melt and its successors is so fascinating that yours truly believes that our blog / bulletin / thingee should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this year is out, of writing an article and putting it online.

And here is the test announced at the beginning of this article.

You are in a field with a weed-eating goat tethered to a stake by a 12 metre (39 feet 4.5 inches) long rope. The stake is 6 metres (19 feet 8.25 inches) from a fence. Choose the better option among the choices below:

A - Calculate the area over which the goat can perform its weed eating duties.

B - Move the stake at least 12 metres (39 feet 4.5 inches) away from the fence and make the calculations.

C - Accuse your local school board of cruelty to a poor and defenceless animal and have the test cancelled.

This writer wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)