Canada’s introduction to a deadly game of drones: An all too brief look at the Canadian career of the SAGEM Sperwer tactical unpiloted aerial vehicle, part 1

Greetings, my reading friend, and profuse apologies. Unable to restrain my wing nutty tendencies any further, yours truly has strayed into the tangled forest that was / is military procurement. Yes, I did. And I am taking you with me down that garden path. More specifically, I would like to disentangle the convoluted story of a piece of military hardware, the SAGEM Sperwer tactical unpiloted aerial vehicle, whose acquisition was announced by the Department of National Defence 20 years ago this month, in August 2003, and…

All right, all right, you got me. Yours truly also wanted to highlight one of the innumerable items in the world class collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario.

Now, to answer the question which is gradually coalescing in your little noggin, a tactical unpiloted aerial vehicle is an unpiloted aerial vehicle (UAV) / drone of a certain size able to operate for up to several hours at a relative low altitude (up to 5 000 or so metres (16 500 or so feet) perhaps) to help a military force achieve a certain objective. A tactical UAV is much larger than a hand launched UAV and much smaller than a long-range UAV.

So, are you ready? Wunderbar! Let us proceed.

The Société d’applications générales de l’électricité et de la mécanique (SAGEM) was founded in Paris, France, in 1925 by a young engineer by the name of Marcel Môme. The firm grew quickly as it diversified its activities, from film cameras and projectors to electricity distribution systems.

In 1939, SAGEM became a significant player in the French telephone industry when it took over the Société d’applications téléphoniques, a communications firm which later became the Société anonyme de télécommunications (SAT).

While that factoid may seem of no interest or importance to you, my reading friend, the truth was / is that SAT was one of the three firms involved in the development of the jet-powered Canadair CL-289 UAV project several decades later. The other firms were West Germany’s Dornier Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung and Canadair Limited of Cartierville, Québec, Canada, a crown corporation at the time

Successfully tested in March 1980, I think, the CL-289 or, as it was / is officially known, the Canadair AN/USD-502, went into service with the Heer, in other words the German army, in November 1990. More than 250 CL-289s were eventually delivered to that service and the Armée de Terre of France. And no, given the decreasing size of its European commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Department of National Defence did not see fit to order that very successful UAV. Incidentally, the Esercito italiano, in other words the Italian army, received a number of second-hand CL-289s around 2002.

And yes, there is a CL-289 in the astonishing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, but back to our story.

By the early 1990s, SAGEM was well known for its involvement in fibre optics, high voltage transmission lines, pay television decoders, telecommunications equipment, etc. As impressive as the firm’s progress was, we are getting ahead of our history.

One could argue that the story of the Sperwer began in March 1983, with the first flight of a target drone, the Banshee, designed by the English firm Piper Target Technology Limited, a firm later known as Target Technology Limited (TTL). That low cost, remotely piloted drone proved to be one of the most successful, if not the most successful in the world in its category. More then 5 000 of those small piston-powered target drones have been built over a period of 20 or so years, if not more, by TTL and, as this firm seemingly became, Meggitt Defence Systems Limited, a subsidiary of the English aerospace and defence production firm Meggitt Public Limited Company.

Over the years, Banshees served in almost 40 countries around the globe.

In the late 1980s or very early 1990s, TTL developed a surveillance version of the Banshee. Known as the Spectre, that UAV had an increased range and endurance, as well as a larger payload. Yours truly cannot say if the surveillance UAVs apparently acquired by the Pãkistãn Fãuj, or Pakistani army, in 2001 were Spectres per se or some sort of surveillance version of the Banshee.

A brief digression if I may. Given the secretive nature of the global arms trade, you may wish to note that the preceding information, as well as the information which follows, was / is not based on secret conversations in dark alleys. That information might therefore prove to be inaccurate to a historian examining this file in 2123, provided our species does not snuff / whack itself out of existence before that of course.

Another brief digression if I may. TTL and Boeing Canada Technology Limited of Winnipeg, Manitoba, a subsidiary of Boeing of Canada Limited of Winnipeg, I think, itself a subsidiary of the American aerospace giant Boeing Company, collaborated in the late 1980s to develop the Vindicator II, a target drone which appeared to be derived from the Banshee.

The Canadian armed forces have fielded, since 1999, and may still field a number of Vindicator IIs, under the designation Meggitt CU-162 Vindicator. One of those very successful target drones can be found in the world class collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

If you must know, Boeing of Canada was mentioned in March 2019 and October 2021 issues of our fascinating blog / bulletin / thingee. Boeing, on the other, was mentioned several times in that same publication, and this since November 2017.

In any event, SAGEM was intrigued by TTL’s UAVs and acquired their French production rights. Let us not forget that UAVs appeared to have a promising and profitable future at the time, especially when developed for military uses.

SAGEM soon, yes, my reading friend, in the early 1990s, developed its first surveillance UAV, a French version of the Spectre for all intend and purposes, the SAGEM Crécerelle. The firm paid for this work with its own moolah, as a private venture.

A SAGEM Crécerelle tactical unpiloted aerial vehicle of the Armée de Terre, somewhere in France, date unknown. http://www.defense.gouv.fr/terre/decouverte/materiels/renseignement/crecerelle (Webpage accessed in 2009)

As this was taking place, undisclosed problems with the Eurodrone Brevel, a Franco-German piston-powered surveillance UAV under development, were causing a certain discomfort within the Armée de Terre. By 1993, it could not wait any longer and ordered some Crécerelles. That UAV went into service in 1995. At least a dozen was produced. The Crécerelle was one of the first European-designed UAVs to become operational in Europe.

An extended range version, the Crécerelle-LR, under study around 2003 for the Armée de Terre, was apparently not produced, and neither was the Brevel, at least not under that name.

You see, the Armée de Terre dropped out of the Brevel programme in the late 1990s or early 2000s. The Heer, however, acquired a number of Rheinmetall DeTec Kleinflugzeug für Zielortung (KZO), as the Brevel became known when it became an entirely German programme. Deliveries began in November 2005. Sixty or so KZOs were delivered to the Heer.

Incidentally, the Groupement d’intérêt économique Eurodrone had been formed in 1989 by Matra Société anonyme and Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, a German aerospace giant mentioned in an April 2019 issue of our amaazing blog / bulletin / thingee, and… Yep, that Messerschmitt, and you are the one who is digressing, my reading friend.

In 1994, SAGEM developed a faster and longer ranged version of the Crécerelle specifically for the export market. Mind you, the firm also knew that the Armée de Terre was quite pleased with its Crécerelles, and might have been interested in acquiring an improved version of it.

Interestingly, SAGEM was also considering the possibility of producing under license a version of the General Atomics MQ-1 Predator, a long range American UAV put into service by the United States Army in the summer of 1995.

A SAGEM Sperwer tactical unpiloted aerial vehicle of the Koninklijke Landmacht, somewhere in Sweden, May 2006. Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, 2154_D060511IG1762.

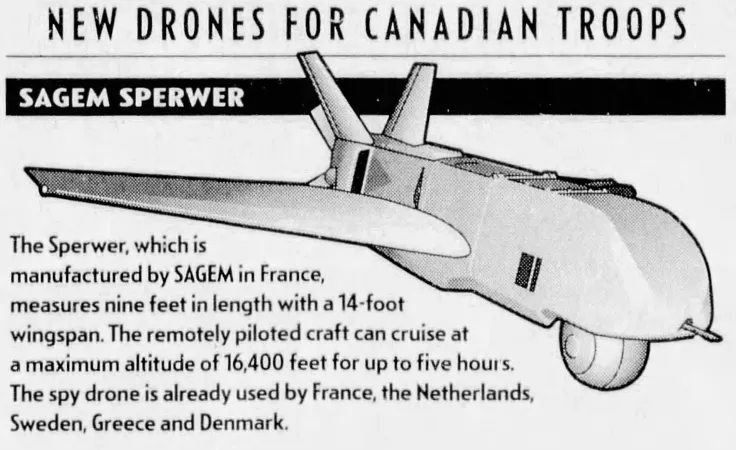

In any event, the extensively redesigned Crécerelle, larger, boxier, more powerful and much heavier than its predecessor, known as, you guessed it, the Sperwer, a word pronounced spare-were, was ordered by the Koninklijke Landmacht in mid-1996. A prototype of that UAV apparently flew later that year. The Koninklijke Landmacht, or Netherlands army, seemingly received 35 or so Sperwers and 4 ground stations. Deliveries seemingly began in 1999.

Additional orders soon came in, from the Armén, or Swedish army, for example, which ordered 10 or so Sperwers and 3 ground stations. Those Sperwers, locally known as SAGEM UAV 01 Ugglans, may have been specially equipped to deal with Sweden’s frigid winters. The Hærens, or Danish army, signed an order as well, for 10 or so Sperwers and 2 ground stations. Those Sperwers were locally known as Tårnfalks. The Ellinikós Stratós, or Greek army, in turn, ordered 15 or so Sperwers and 4 ground stations but I cannot say if those UAVs got the name of a local birdy, and…

Yes, my puzzled reading friend, the words sperwer, ugglan and tårnfalk all refer to birds of prey, namely a sparrowhawk, an owl and a kestrel.

It is worth noting that the Armée de Terre, finally, chose the Sperwer to replace its Crécerelles. And yes, that decision was made not too, too long after that service pulled out of the Brevel program. The French version of the Sperwer was known as the Système de drone tactique intérimaire (SDTI), in English interim tactical drone system. Deliveries began in 2003-04. A second batch was ordered in 2009, and a third in 2012, and a fourth in 2013, for a total of 30 or so brand new SDTIs / Sperwers and an unknown number of ground stations.

The UAVs ordered in 2012-13 were examples of a second, larger, heavier and longer-range version of the Sperwer, a version tested in 2004 but first proposed as early as 2001, I think.

And yes, even though it was an interim system, the SDTI remained in service until 2020, I think. Again.

Interestingly enough, in 2013, production of the larger, heavier and longer-range version of the Sperwer seemed on the verge of starting in Ukraine. The work was to be done by Derzhavne Pidpryyemstvo “Chuhuyivs’kyy Aviaremontnyy Zavod,” in other words the state enterprise “Chuhuiv aircraft repair plant.” That project seemingly went out the window when, as a result of the Maidan Revolution / Revolution of Dignity / Ukrainian Revolution of February 2014, the evil empire better known as the Russian Federation invaded the Ukrainian autonomous republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, and assisted Russophone rebels in their partial takeover of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions / provinces of Ukraine.

All in all, SAGEM produced 140 or so Sperwers, all versions included, as well as 25 or so ground stations. One could argue that, in its day, the Sperwer was the most commercially successful UAV produced in Europe.

The Sperwer was launched from an inclined pneumatic launch ramp / catapult mounted on a truck or trailer. Throughout the flight, an operator on the ground could rotate the large sphere under the nose, a sphere which contained a video camera, or an infrared camera for night flights. Real time images were continuously sent back to base. Mind you, the operator could also lock the video camera onto a particular spot on the ground while the Sperwer turned around it, under the control of its pilot.

If something interesting turned up on the ground, the Sperwer could be instructed to fly directly toward it. A fixed video camera in the nose gave its pilot a wide-angle view of his flight path.

The recovery of the Sperwer was accomplished via a parachute, once the engine was shut down. Almost any flat piece of land devoid of trees could serve as a landing area. Three airbags under the nose and wings cushioned the landing and reduced the risk of damage.

The Sperwer system was designed to be relatively mobile. The ground control stations were mounted on trucks, for example. The various vehicles required to control the Sperwers, not to mention the launch ramp and spare UAVs, could be carried aboard several transport planes similar in size to the Lockheed CC-130 Hercules of the Canadian armed forces, a type of machine represented in the stupendous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The Sperwer was a tad unusual in that it had a liquid-cooled piston engine, produced by Bombardier-Rotax Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, an Austrian subsidiary of Bombardier Incorporée, a Québec industrial giant mentioned many times in our spectacular blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018. SAGEM engineers might have thought that such a type of engine would be less noisy than an air-cooled engine, which would make it harder for people on the ground to locate a Sperwer buzzing around them.

And yes, my reading friend, Bombardier-Rotax was indeed mentioned in an August 2023 issue of our magnificent blog / bulletin / thingee.

The four-blade propeller, at the rear, was made of wood – an odd choice at first thought, but a very practical one indeed. A wooden propeller easily broke apart if a landing was rough, thus preserving the valuable engine from damage.

And yes again, your instincts are quite correct, my reading friend. The Canadian armed forces came knocking on SAGEM’s door at some point. You will, however, have to wait a few days to figure out how that knocking panned out. Sorry. Or not.

Ta ta for now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)