I love the clouds… the clouds that pass… over there… over there… the marvelous clouds! The Établissements Fouga et Compagnie and its jet-powered gliders

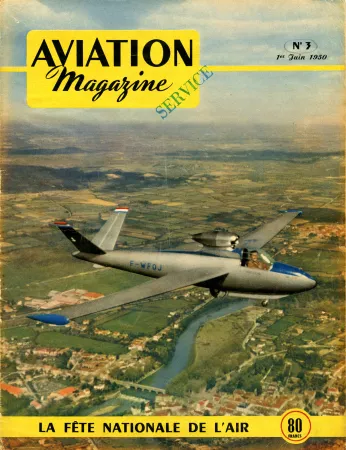

Greetings, my reading friend. I would like to talk to you about a subject that caught my attention as I was browsing an excellent though somewhat chauvinistic French periodical, the bimonthly Aviation Magazine – specifically the 1 June 1950 issue of said magazine.

Anxious to place our subject of the week in its historical context, allow me to begin this peroration well before the first flight of the aircraft of which we have just seen the photograph.

In 1919, the French engineer Gaston Fouga founded a railway equipment repair firm, the Établissements Fouga et Compagnie. In September 1935, aware of the fact that the French government wanted to strengthen the national air force, the Armée de l’Air, the firm hired the most important members of the design office of a small aircraft manufacturer on the verge of bankruptcy, the Société anonyme des avions Bernard. The design office thus created seemed to close in March 1936.

This being said (typed?), the Établissements Fouga did not give up aeronautics. The firm acquired the rights to build the light / private aircraft designed by engineer Pierre Mauboussin and began production of 50 Salmson D6 Cri-Cri light / private aircraft, one of the most popular French aircraft of this type of the interwar period. Indeed, these Cri-Cri were intended for the flying schools of the Aviation populaire, a quasi-revolutionary concept for the France of the time which was launched by Pierre Cot, the Air minister of the socialist government elected in 1936.

The occupation of France by National Socialist Germany which lasted from 1940 to 1944 considerably reduced the aeronautical and non-aeronautical activities of the Établissements Fouga. The firm may, however, have manufactured flat bottom canoes which were highly appreciated by fishermen and hunters.

Deemed guilty of having collaborated with the German occupier, Gaston Fouga saw his firm confiscated by the French government in 1944. He died in August of that same year.

In 1945, the Établissements Fouga began manufacturing light / private aircraft designed by Mauboussin and gliders designed by Mauboussin in collaboration with engineer Robert Castello.

Around 1948-49, Mauboussin, absent minded, courteous, dreamer, modest and nonchalant, met Joseph Szydlowski, born Józef Szydłowski, the hot but brilliant co-founder of the Société Turbomeca, a manufacturer of piston engine superchargers and small jet engines. The idea came to them to mount a tiny turbojet engine on a CM-8 type glider designed by Castello and Mauboussin but manufactured by the Établissements Fouga. This small wood and metal aircraft, the smallest jet aircraft in the world, the CM-8 Cyclone, flew for the first time on 14 July 1949. Long live France – and French fries!

Having heard of the new French aircraft, the Wright Aeronautical Division of the American aeronautical giant Curtiss-Wright Corporation, well known for its Cyclone engines (Cyclone, Twin Cyclone, Dupleix Cyclone), asked the Établissements Fouga to find a new name for it. A little perplexed perhaps, the French firm complied. Its Cyclone became the Sylphe.

The Établissements Fouga shipped the Cyclone / Sylphe to Miami, Florida, in January 1950. Presented by an excellent pilot, the small aircraft impressed many representatives of the American aeronautical industry. Turbomeca also received several requests for information. And yes, my reading friend, I too wonder if the request from Curtiss-Wright’s Wright Aeronautical Division was a direct result of the demonstration flights carried out in Florida. Anyway, let’s move on.

A more powerful version of the Cyclone / Sylphe, the CM-8 Cyclope, took to the sky in August 1950. Another, a rather original one, the CM-88 Gémeaux (8 and 88, Gémeaux / Gemini, get it? Sigh…), made its first flight in March 1951. And if you are very nice, as good as gold, yours truly undertakes to consider the possibility of thinking about writing an article on this unique flying machine.

In 1952, the Établissements Fouga manufactured 8 examples of a racing version of its aircraft. These CM-8 Midgets (Midjets?) were intended for a newly created firm which wished to organise air races in Paris, then in France, in French North Africa (Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia) and in Europe. Les Courses aériennes, as it was called, underlined that each Midget would wear the colors of a large French firm. It firmly intended to ask French and foreign pilots to participate in the competitions. Each of them would be assigned to an aircraft by lot before each race. The Club aérien de Paris would hold the first of these (weekly?) competitions in May 1952. And yes, rejoice, my reading friend with a taste for risk, spectators could bet on the results of the races.

Caricature of the daily Le Parisien libéré concerning the air racing project of the firm Les Courses aériennes. The caption reads: “Why do you want me to risk everything on a competitor whose mother I don’t even know!” Anon., “Actualité aéronautique – Courses de midgets à réaction.” Aviation Magazine, 1 December 1951, 29.

An interesting detail, legend had it that, to meet the conditions imposed by the Fédération aéronautique internationale, the world governing body for all manners of aeronautical records mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since January 2018, in light aircraft competition, i.e. those weighing less than 500 kilogrammes (just over 1 100 pounds), the Établissements Fouga had to nitpick a little. Okay, okay, they have to nitpick as much as possible.

Let me explain. Assuming that a Midget pilot weighed 75 kilogrammes (165 pounds), said aircraft tilted the scales at 499.9 kilogrammes (just over 1,100 pounds) if it carried 74.9 kilogrammes (165 pounds) of fuel – a mass consumed in 25 minutes at most. A period of time which could correspond to the duration of a race. Theoretically.

It is with sadness that yours truly must inform you that this air racing project did not lead to anything concrete. Unless I am mistaken, even the first race was canceled before it took place.

This being said (typed?), I would be remiss if I did not mention the fact that the work accomplished by the Établissements Fouga and Turbomeca since the design of the Cyclone gave birth to a more powerful turbojet engine and to a two-seat twin-engine aircraft intended for the training of military pilots. The prototype of this Fouga CM-170 Magister flew for the first time in July 1952. The aforementioned Armée de l’Air received its first aircraft in March 1956.

Would you believe that in 1954 a committee of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization recommended / suggested that member countries, including Canada, use the Magister to train their pilots? In fact, only France, Belgium and West Germany followed this recommendation / suggestion. This being said (typed?), more than 20 countries in Africa, America and Europe used this elegant flying machine for many years. Just over 1 000 Fouga / Potez Air-Fouga / Sud Aviation Magisters were produced in France, but also in West Germany, Israel and Finland. The Magister was / is one of the best jet trainers of the 20th century.

Do you have a question, my reading friend? Why didn’t the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) use the Magister? A good question. You see, during the 1950s, the RCAF used the Lockheed T-33 Silver Star to train its jet aircraft pilots. And yes, the collection of the fabulous Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Silver Star, manufactured under license by Canadair Limited of Cartierville, Québec, a subsidiary of the American defence industry giant General Dynamics Corporation.

Canadair was obviously mentioned many times in issues of our you know what, and this since November 2017. General Dynamics was mentioned a bit less often, and this since March 2018.

This being said (typed?), the RCAF began to think of replacing the Silver Star in the mid-1950s. In 1956, for example, it became more and more interested in a concept put forward in the United Kingdom by the Royal Air Force: the exclusive use of jet aircraft fitted for the training of combat crews. In fact, the RCAF considered proposing the purchase of the production rights of the Hunting Percival Jet Provost, the two-seat single-engine aircraft used for this purpose. Canadair hoped to land an order.

This project having sunk into oblivion, the Québec aircraft manufacturer changed its strategy. One project in particular gained more and more supporters: the design and manufacture of a military training aircraft. Management weighed the pros and cons; the risks of such a private project were numerous. Towards the end of 1957, Canadair embarked on the development of its first original, and internally funded, aircraft. The prototype of this CL-41 flew in January 1960. The RCAF announced its intention to purchase 190 examples of this aircraft in September 1961. Canadair delivered the first CT-114 Tutor in December 1963. This aircraft was / is one of the most successful training aircraft of its time.

It should be noted that the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, just as fabulous as it was 3 paragraphs before, includes a Tutor wearing the colors of the Snowbirds, the aerobatic team of the Royal Canadian Air Force. A second, historically more important Tutor is located in the entrance hall of the museum.

If you don’t mind, yours truly will leave you to go about his important daily business.

Have you seen my pillow, my reading friend?

More Stories by

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)