Burning the midnight oil to reach for the sky and roar: The all too brief saga of the Rohr M.O.1 Midnight Oiler light / private plane

Top of the morning to you, my reading friend.

At the risk of repeating myself, yours truly will readily admit that I have had, have and will presumably continue to have a strong affinity toward the unusual, the strange, the odd looking, etc. Juggling that fact while balancing a wish to commemorate an anniversary, I chose to temporarily put aside the anniversarial approach of our awesome blog / bulletin / thingee to offer myself a wee present.

Before we get there, however, it might prove useful to go over the origin story of the firm responsible for the item at the heart of today’s peroration.

Founded in August 1940 by Frederick Hilmer “Fred / Pappy” Rohr with the help of Reuben Hollis Fleet, the president of a major American aircraft manufacturing firm, Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, Rohr Aircraft Corporation was one of the first, if not the first major North American maker of prefabricated aircraft components, or aerostructures, which could be put in place in minutes by the staff of aircraft manufacturing firms.

By the way, did you know that, back in 1927, Rohr was a valued employee of Ryan Aeronautical Corporation, the American aircraft manufacturing firm which put together a unique machine, the Ryan NYP, piloted across the Atlantic Ocean in May 1927 by an individual mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2017, namely Charles Augustus Lindbergh? Indeed, Rohr was heavily involved in the design and fabrication of the fuel tanks of that historic aircraft.

Oh, and before I forget, Fleet founded Fleet Aircraft of Canada Limited in Fort Erie, Ontario, in April 1930, to produce basic training aircraft which would be of interest to the Royal Canadian Air Force, to Canadian flying clubs and to foreign air forces.

That little digression of mine now allows me to point out that the estradinary and velmarlous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a Fleet Finch, a Fleet Freighter and a Fleet Canuck. Yours truly had the pleasure of pontificating about the latter two in September 2020 and May 2021.

By the way, again, Fleet was mentioned in a May 2021 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Fleet Aircraft, on the other hand, was mentioned twice therein, in March and… May 2021. Consolidated Aircraft, finally, was mentioned several times in our you know what, and this since February 2019. The world revolves around our glorious blog / bulletin / thingee, do you not think, my reading friend? But back to our story.

As you well imagine, Rohr Aircraft grew by leaps and bounds from 1940 onward. The sudden end of the Second World War, in September 1945, caught it, and the rest of the American aircraft industry, by surprise. The cancellation of military contracts led to massive layoffs to which Rohr Aircraft was not immune. It went from 9 500 or so employees in 1944, most of them women, to less than 1 000 employees, almost all of them men, in 1946.

By then, however, Rohr Aircraft was no longer an independent firm. Nay. In March 1945, convinced that the future of his company laid in the production of consumer products for the countless veterans of the United States Army and United States Navy who would start families after the end of the Second World War, Rohr agreed to merge it with a well known American manufacturer of machine tools, radio equipment and land mine detectors. Rohr Aircraft officially became a subsidiary of International Detrola Corporation in July.

In spite of that, the early postwar period was no picnic for Rohr and his massively reduced workforce. They went from making aerostructures vital to the American war effort to making washing machines, vacuum cleaners, radio cabinets and toy boats. Rohr was by no means happy with these products but saw them as the only way to save his creation.

Mind you, Rohr Aircraft did not turn its back on the aircraft industry. Nay. In 1946, for example, it joined forces with an aging American aeronautical giant mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2017, Curtiss-Wright Corporation, to develop an easily-attached prefabricated engine nacelle which could easily be mounted on war surplus Douglas C-54 Skymaster 4-engine military transport planes converted into Douglas DC-4 airliners. The engine in said nacelle would lead to increases in speed, payload, and profit. At least one American air carrier, Chicago and Southern Airlines Incorporated, acquired a number of Wright-Rohr power units for installation on its DC-4s.

Incidentally, the Skymaster was / is a cousin of the Douglas / Canadair C-54 North Star military transport planes, a type of machine present in the stupendous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, but back to our story.

It truth be told, Rohr Aircraft gradually reinvented itself as a manufacturer / designer of engine nacelles for airliners and military transport planes.

And this was by no means the only postwar aeronautical project Rohr Aircraft was involved in. Nay again. You see, rumours concerning its entry into the personal plane market began to percolate in the early fall of 1945. Why was that so, you ask, my curious reading friend? Well, you have to understand that a great many people thought that a significant percentage of the hundreds of thousands of American military pilots trained during the Second World War, men who lived in urban and rural areas, would want to keep on flying after the end of that dreadful conflict. Indeed, a far greater number of American men of similar age who had not served as pilots, men who also lived in urban and rural areas, would want to cavort / frolic with them among the clouds.

The figures bandied about by various individuals seemed extremely, if not amazingly promising in that regard: 400 000 prospective buyers according to a 1946 issue of the respected monthly magazine Aero Digest and 1 000 000 (!) prospective buyers according to a 1945 report by Victor Perlo, an economist / statistician who was Chief of the Industry Research Branch of the Bureau of Program and Statistics of the War Production Board.

Incidentally, Perlo was a hard core member of the Communist Party of the United States of America who, as a member of the so-called Ware Group and head of the co-called Perlo Group, provided sensitive / confidential / secret information to the government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics between 1933 and 1947-48, when his loyalty was publicly questioned by the (in)famous House Committee on Un-American Activities of the United States House of Representatives. He left a government position in 1947 but was never prosecuted. Perlo might, I repeat might, have remained a true believer until the day he died, in December 1999, at the age of 87, but I digress.

Given the aforementioned predictions, was it a surprise that a great many light / private plane manufacturers came into existence in the United States from 1945 onward?

Incidentally, Rohr himself was initially against the idea of developing one or more aircraft in house. He felt / feared that some of Rohr Aircraft’s largest customers would see such work as an unwelcome attempt to compete with them. In the end, the troubled times his firm was going through convinced Rohr of the potential usefulness of funding the development of a single aircraft.

Most of the machines developed by these firms were conventional aircraft with a conventional appearance. Two of the many, and yours truly really means many, many types of light / private planes under development from 1945 onward attracted a great deal of attention, however, because they were definitely not conventional aircraft with a conventional appearance.

Now, who do you think would forego conventionality in favour of more innovative approaches? Rohr Aircraft, you say (type?), my reading friend? Good guess, but then I was sort of leading you by the hand to that conclusion, now was I not?

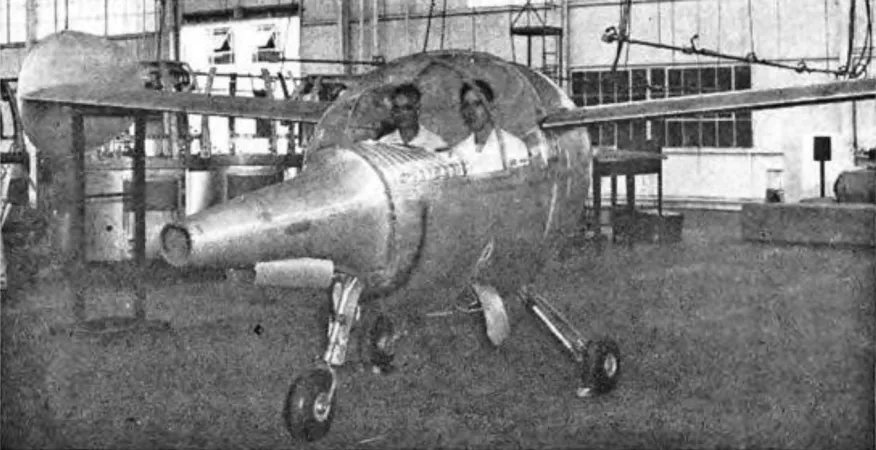

The aircraft whose development was reluctantly approved by Rohr, an aircraft designed by the firm’s chief aeronautical engineer, Frank McCreary, was the Rohr M.R.1, a 2-seat light / private plane with forward swept wings and a Vee tail / butterfly tail.

After putting together a full size mock-up of the M.R.1, Rohr aircraft’s personnel fabricated 2 examples of the actual aircraft. One of them was used for load testing while the other became the flight test prototype.

The test pilot who took up that small machine, in 1947, I think, was not impressed. The M.R.1, he stated, was not safe to fly. Although fitted with a more powerful engine and a stabilising fin under its rear fuselage, that prototype never flew again.

The one and only Rohr M.R.1 as modified after its first and only flight, Chula Vista, California. Anon., “Have you seen?” Flying, June 1947, 47.

Donated to the Aerospace Museum, in San Diego, California, near Chula Vista, the M.R.1 was partly destroyed in an arson fire in February 1978 which destroyed 50+ aircraft. Only its wings survived. As of 2023 these were stored in York, Pennsylvania – possibly at the airport operated by York Aviation Incorporated, a firm owned by Stewart Group Incorporated.

It should be noted that the nickname Guppy sometimes associated with the M.R.1 was given well after that aircraft was grounded.

It should also be noted that the M.R.1 was still under wraps when the other light / private plane developed by Rohr Aircraft was mentioned and shown in the aeronautical press, and this from July 1946 onward. That 2-seat flying machine was / is of course the one mentioned in the title of this article of our staggering blog / bulletin / thingee, namely the Rohr M.O.1 Midnight Oiler, and…

I recognise the hand of my reading friend poking though the ether. Why was this aircraft called Midnight Oiler, you ask? A good question. Some have suggested that this moniker derived from the fact that this flying machine looked like an oil can, which was not necessarily what a future proud owner of an M.O.1 wanted to hear at every airfield he or she landed on.

Others have suggested that the moniker derived from the fact that most of the design work and much of the early construction work, in the spring and summer of 1946, was done in the wee hours of the morning, or the late hours of the evening, or both. Indeed, it looked as if said design and construction work was done during those unusual time slots because the project initially did not have an official sanction.

In any event, the M.O.1 was most definitely an unconventional aircraft, and… You have forgotten how it looked, have you not. Sigh… What is it with people these days? They have the attention span of a hare brained flea. Here is a drawing of what the M.O.1 would have looked like in flight, courtesy of Coq hardi, a very popular but declining French illustrated weekly magazine aimed at a young audience.

An artist’s view of what the Rohr M.O.1 would have looked in flight. A top view of the aircraft is in the upper right corner. And yes, it would fly from right to left. Noël Graveline, “Coq hardi ‘Drôle de coucou’ Mickey Mouse.” Coq hardi, 26 May 1949, no page number.

The M.O.1 was indeed an odd looking bird, a “drôle de coucou,” to quote the title of the article in Coq hardi. Indeed, would you believe that the author of said article stated that the long nose and wingtip vertical surfaces of the M.O.1 reminded him of… Mickey Mouse, a supremely well known American comic strip / cartoon character present in France since 1934?

The M.O.1 was actually a canard and that, my reading friend, was / is no canard. A canard being of course a false / unfounded story or groundless rumour as well as an aircraft whose horizontal stabiliser and elevators are located in front of its wing.

Is that a lightbulb moment you are experiencing, my reading friend? Was the Aerial Experiment Association Aerodrome No. 4 Silver Dart a canard, you ask? Why, the first powered aeroplane to make a controlled and sustained flight in Canada was indeed a canard. Very good.

The word canard was / is one of the French words appropriated by the English language to describe various elements of an aircraft, from fuselage to aileron. The English translation of the word canard is of course duck. A duck bird has a long neck and rear mounted wings while a canard aircraft has a long forward fuselage and rear mounted wings.

By the way, yours truly has to admit that I am in agreement with an old and powerful computer program, a real rogue in fact, who exists within the Matrix. Like the Merovingian, “I love the French language. Fantastic language. Especially to curse with,” but I digress. Merde. Now, do not be shocked, my puritan reading friend. If the great Jean Luc Picard can say that word, twice, so can I – and so can you. (Hello SB, EG and EP!)

Very nice, if a tad loud. You might want to close the patio door. You really freaked out the voles.

If I may quote, out of context, the lead singer of the very popular 1980s American new wave band Talking Heads, you may ask yourself why the tooling supervisor / superintendent at Rohr Aircraft, Burt F. Raynes, designed a canard light / private plane rather than a conventional one. The answer to that question was / is to be found in a statement made by Raynes himself:

We must face unpleasant facts and realize that personal planes are noisy, vibrating, unsatisfactory contrivances designed to transport human beings from one place to another with less safety and at greater expense than any other form of transportation.

At the risk of stirring a hornet’s nest, one could argue that this mid 1940s observation remained surprisingly valid in 2023, but back to our story.

Raynes chose to design a canard light / private plane to deal with the many issues which plagued the conventional light / private planes available in 1945. He also chose to design his machine so that it could manipulate / control the very thin layer of air around its wing and horizontal stabiliser. That very thin layer of air was / is known as the boundary layer.

Please, and I do mean please, note that was follows is an (over?) simplified version of what actually happens. Yours truly is not an engineer.

When air flows over a wing, it encounters some friction which slows down the movement of the air in contact with said wing. That friction slows the movement of the air to such an extent that, at the very surface of the wing, there is no movement at all. Right above that infinitesimally thin layer of air lies another infinitesimally thin layer of air which moves very, very little. Above that lies another layer of air which moves a teeny tiny bit faster, and so on. Each succeeding layer moves at a faster rate relative to the one below until that speed reaches the speed of the free flowing airstream.

The region in which the speed of the air changes from zero at the immediate surface of a wing to the speed of the free flowing airstream, very often no more than 1 to 2 millimetres (0.04 to 0.08 inch) in thickness in the case of a light / private plane like the M.O.1, is known as, you guessed it, the boundary layer.

And yes, as incredible as it may seem, it is within that very, very thin region that the speed of the air increases from 0 kilometre/hour (0 mile/hour) to the 240 kilometres/hour (150 miles/hour) the M.O.1 was supposed to achieve.

And if you think that was / is quite the jump, my reading friend, remember that the speed of the air flowing across the wing of a high flying Lockheed F-104 Starfighter jet fighter went from 0 kilometre/ hour (0 mile/hour) to 2 335 kilometres/hour (1 450 miles/hour) within a boundary layer which might not have been a lot thicker than that of the M.O.1. And yes, there is a Starfighter in the astonishing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. Why do you think yours truly chose to mention that aircraft?

To answer the question that will inevitably form in your noggin, Raynes chose to design his machine so that it could manipulate / control its boundary layer because that manipulation / control would, he thought, increase lift, reduce drag and improve controllability.

Raynes hoped to achieve that control by using a blower which would suck the air flowing along the fuselage of the M.O.1 through narrow slots all around the rear fuselage. Sucking in that air would reduce drag quite significantly and improve the flow of air to the rear-mounted propeller, or so he hoped.

The air sucked in through the aforementioned circumferential slots would flow over the air cooled engine of the M.O.1, thus keeping it happy, before being channelled through both wings, as well as to the forward fuselage and through both halves the horizontal stabiliser. The air in question would be discharged through narrow slots over most of the length of the upper surfaces of the wings and horizontal stabiliser to increase lift, reduce drag and improve controllability.

By the way, to further reduce drag, Raynes gave his creation a retractable landing gear.

A diagram showing the flow of air through the fuselage of the Rohr M.O.1. Maurice Victor, “Une curieuse conception de l’avion privé – Le M-O.1, avion ‘canard’ biplace réalise le contrôle de la couche limite.” Les Ailes, 22 February 1947, 4.

And no, the vertical surfaces at the tips of the wings did not include rudders and… How could the M.O.1 be controlled from left to right, in other words in yaw, if it did not have a rudder, you ask, my worried reading friend? Fear not. You see, to make a left turn, for example, the pilot of the M.O.1 only had to rotate the control wheel to the left. That rotation partly stopped the flow of air over the left wing, which reduced the amount of lift created on the left side of the M.O.1. The left wing went down a bit. That downward movement, combined with the larger lift resulting from the uninterrupted flow of air over the right wing, initiated the turn to the left that the pilot wanted to accomplish.

As designed by Raynes, the M.O.1 was to be a relatively inexpensive and easy to maintain and repair machine which could not be stalled. To facilitate storage and transport, the wings of the aircraft could be detached.

Before I forget, Raynes modified various major components of the aforementioned M.R.1 to hasten the assembly of his M.O.1.

The sad truth, however, was / is that the M.O.1 never made a left turn, or a right one, for that matter. You see, it never left the ground. Indeed, one has to wonder if the nose section which included the aircraft’s horizontal stabiliser was mounted at all.

Why proceed that far and not make at least a hop aboard the M.O.1, you ask, my puzzled reading friend. A good question for which I have no answer. Did the unfavourable flight test report of the M.R.1’s first and last flight play a role? Did the management of International Detrola or that of Rohr Aircraft put the kibosh on the project? Who knows…

If truth be told, Rohr aircraft’s gradual reinvention as a manufacturer / designer of engine nacelles for airliners and military transport planes was the main culprit. That line of work was far more promising that light / private plane manufacturing. The already limited resources to the M.O.1 project were gradually reduced until said project was simply cancelled.

Mind you, the March 1948 transfer of Raynes to International Cooler Corporation, an International Detrola division acquired in 1945, probably did not help.

The M.O.1 was probably scrapped even before the end of the 1940s.

The failure of the M.R.1 and M.O.1 did not significantly affect the future of the postwar light / private plane boom, however. You see, by the time the hundreds of thousands of unmarried American military pilots trained during the Second World War and the greater number of unmarried American men of similar age who had not served as pilots bought some new clothes and their engagement ring, got married, bought a house with a white picket fence and garage, bought the big automobile of their dreams and the gasoline needed to use it, bought a big friendly Canis lupus familiaris, bought the groceries, bought a crib, tons of baby food and plenty of diapers, there was no moolah left to buy a light / private plane.

The much anticipated and hoped for boom in light / private plane sales and production did not materialise. Most of the new aircraft manufacturing firms set up in the Unites States to take advantage of that unrealised bonanza went under well before the end of the 1940s.

The failure of the M.R.1 and M.O.1 did not significantly affect the future of Rohr Aircraft either. As you already know, the firm was gradually reinventing itself as a manufacturer / designer of engine nacelles for airliners and military transport planes.

Did you know, however, that Rohr Aircraft delivered the power packages of the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, a type of military transport plane flight tested in August 1954 (!) found in the incomparable collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum?

Rohr was very pleased with that gradual reinventing of his creation. He was, however, increasingly unhappy with the way the management of International Detrola or, as it became in February 1949, Newport Steel Corporation was conducting its business.

After hearing that said management wanted to sell Rohr Aircraft, Rohr organised a group of shareholders and employees to launch a bid. The crafty Rohr might even have convinced an influential customer, Boeing Airplane Company, a firm mentioned many times in our you know what since June 2018, to pay in advance the engine nacelles it had ordered so that he could add that dough to the pot of gold he was putting together. When the management of Newport Steel raised the ante by asking for more moolah, Rohr soon matched that ante and won the jackpot.

In November 1949, Harbor Aircraft Corporation, a firm created by Rohr for that very purpose, acquired the assets of Rohr Aircraft, a change in ownership which led to the (re)birth of… Rohr Aircraft Corporation.

As you understand very well, the onset of the Korean War, in June 1950, was a game changer. Military spending ballooned all over the globe. Well, all over North American and Europe anyway. For Rohr Aircraft, the sky was the limit.

By then, the aforementioned Raynes was back at Rohr Aircraft. He gradually climbed the corporate ladder and succeeded Rohr as president in 1963.

Frederick Hilmer Rohr left this Earth in November 1965, at the age of 69.

Rohr Aircraft underwent several / many additional changes of products, ownerships, names and fortunes over the following decades.

One of the products Rohr Aircraft got involved with was an aircraft. In 1974, Raynes, by then chairperson and chief executive of Rohr Industries Incorporated, decided to move into the light / private aircraft market, a very competitive market dominated by a small number of well established firms. He asked a well known American pilot / engineer / model aircraft designer / aircraft designer, Walter E. “Walt” Mooney, to develop an aircraft whose superior safety, performance, efficiency cost, comfort and accessibility would drive the management of American giant Cessna Aircraft Company completely bonkers. An aircraft which would be so amazing that private pilots would not be able to resist its charm / allure.

The design Mooney and his small elite team came up with was very impressive and very unconventional indeed. The Rohr Two-175 FanJet / 2-175 FanJet had a structure made up of composite materials. It had a cropped delta wing which folded so that it could be stored in a standard one automobile garage. Mind you, it also had a folding tailfin for that same reason. The FanJet also had a shrouded / ducted propeller in the rear fuselage. It had a rudder, of course, but that rudder was underneath its nose. Would you believe that this rudder and the fairing of its nose wheel were one and the same? I kid you not.

Mooney’s team fabricated 3 examples of the FanJet. One of them was used for load testing while the other two became flight test prototypes. Yours truly cannot say if both machines actually flew. In any event, the FanJet proved to have pleasant flying characteristics.

Sadly enough, that very promising design was not put in production. You see, Rohr Industries experienced serious financial difficulties during the 1970s. If truth be told, its plans to develop various types of mass transit vehicles (people mover, hovertrain and articulated bus) were going nowhere. They were eventually abandoned. Given the circumstances, development of the FanJet was not deemed worthy of continuation either.

As of 2023, Rohr Incorporated was a unit of Collins Aerospace Incorporated, itself a unit of Raytheon Technologies Corporation, an American yet multinational aerospace / defence conglomerate.

Pastak v’dora lashe / dif-tor heh smusma, my non Vulcan reading friend, and, err, merde.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)