“Canned it is most excellent, being splendid for pies” – The crawling and flowering saga of a slight horticultural mystery of the early 20th century, the loganberry, part 2

That was a mouth-watering image, was it not, my foody reading friend? The loganberry is certainly an interesting aggregate fruit.

Let us unearth more juicy details about its early years.

Loganberry plants began to appear in Canada, in this case British Columbia, no later than 1904 – and quite probably earlier. As was the case in the United States, yours truly presumes that most of their loganberries were canned, preserved or turned into jams or jellies. That was not all, however.

Home-made loganberry wine began to appear in British Columbia no later than 1908 – and quite probably earlier. By the late 1910s, that inebriating beverage was quite popular in that Canadian province. Indeed, it could be bought in numerous locations – and in stores in such locations.

A Swiss Canadian dairy expert (butter, cheese and milk) who had worked in the United States, Léon de Montreux Chevalley, began to cultivate, well, actually, his staff began to cultivate loganberries near South Sumas, British Columbia, near Chilliwack, in 1919, I think. Indeed, he began to bottle loganberry wine no later than 1920.

After 6 or so months spent in wooden barrels, the young wine had the peculiar and appetizing bouquet of a fine Bordeaux, or so claimed de Montreux Chevalley in March 1921. According to him, that beverage was superior to the sour and uncomfortable wines bottled in California.

Given that each hectare (acre) of land planted with loganberries could produce an average of 7 500 to 9 400 or so litres of juice per hectare (720 to 900 or so imperial gallons / 875 to 1 075 or so American gallons per acre), again according to de Montreux Chevalley, British Columbia could produce a sizeable volume of wine.

And yes, such yields might, I repeat might, have been comparable, if not higher than those of land planted with grape vines.

Chevalley Wine Company Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, was incorporated in February 1926. Sadly, Chevalley himself died in June, aged 71 or 72. His firm might, I repeat might, have ceased to operate not too long after.

De Montreux Chevalley was by no means the only person in British Columbia to dream of loganberry wine. Nay. In the spring of 1921, the founding secretary and manager of the Saanich Fruit Growers’ Association of… Saanich, British Columbia, J.H. Sutton, put forward the idea of selling wine made by members of that association in the stores of the province’s Liquor Control Board which were to open in June of that year.

You see, British Columbian loganberry growers had significantly extended their plantations during the First World War as a result of the high prices they were getting. With the (precipitous?) fall in the amounts of preserves made, and the concurrent fall in prices, after the end of the conflict, they found themselves stuck with fields chockfull of loganberries with few buyers in sight. Turning those fruits, err, aggregate fruits into plonk seemed like a good idea.

Although intrigued, the management of the Liquor Control Board seemingly did not bite until June 1923 when the former completed arrangements with 200 or so loganberry growers located in or near Saanich.

Yours truly wonders if that initiative led to the creation of Growers Wine Company Limited of Victoria, British Columbia, a firm incorporated in July 1923. Indeed, the first products commercialised by that firm were Logana, a loganberry wine, and Vin Suprême, a loganberry and blackberry wine. Both products could still be purchased more than 35 years later, as can be seen in the following advertisement.

A typical advertisement issued by Growers Wine Company Limited of Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia. Anon., “Growers Wine Company Limited.” Victoria Daily Times, 11 December 1959, 15.

Would you believe that Growers Wine increased its production approximately 15-fold between 1923 and 1927, a year during which said production hovered around 500 000 or so litres (110 000 or so imperial gallons / 130 000 or so American gallons)? That was a lot of plonk.

And yes, back in the early 1920s, Sutton had produced his own loganberry wine. It was said to be “so good that a tumblerful is more than any automobile driver should drink at a time.”

The projects put forward by Sutton and de Montreux Chevalley might, or might not have inspired, a couple of farmers based in Steveston, British Columbia, near Richmond. You see, James Archibald McKinney and William R. Simpson were unable to sell their first loganberry crop, a bumper one, in 1924. They then set out to turn it into wine. To do so, McKinney might, I repeat might, have acquired a small California winery clobbered by prohibition and moved its equipment to Steveston.

Informed of what was taking place in that village, the aforementioned Liquor Control Board understandably came knocking. It was suitably impressed and so was born the Myrtena brand of loganberry wine, bottled by said control board.

Incidentally, the word Myrtena was a portmanteau which blended more or less precisely the first names of one of McKinney’s daughters, Myrtle Helena McKinney, and of one of his daughters-in-law, Christine McKinney, born Gilmore, I think.

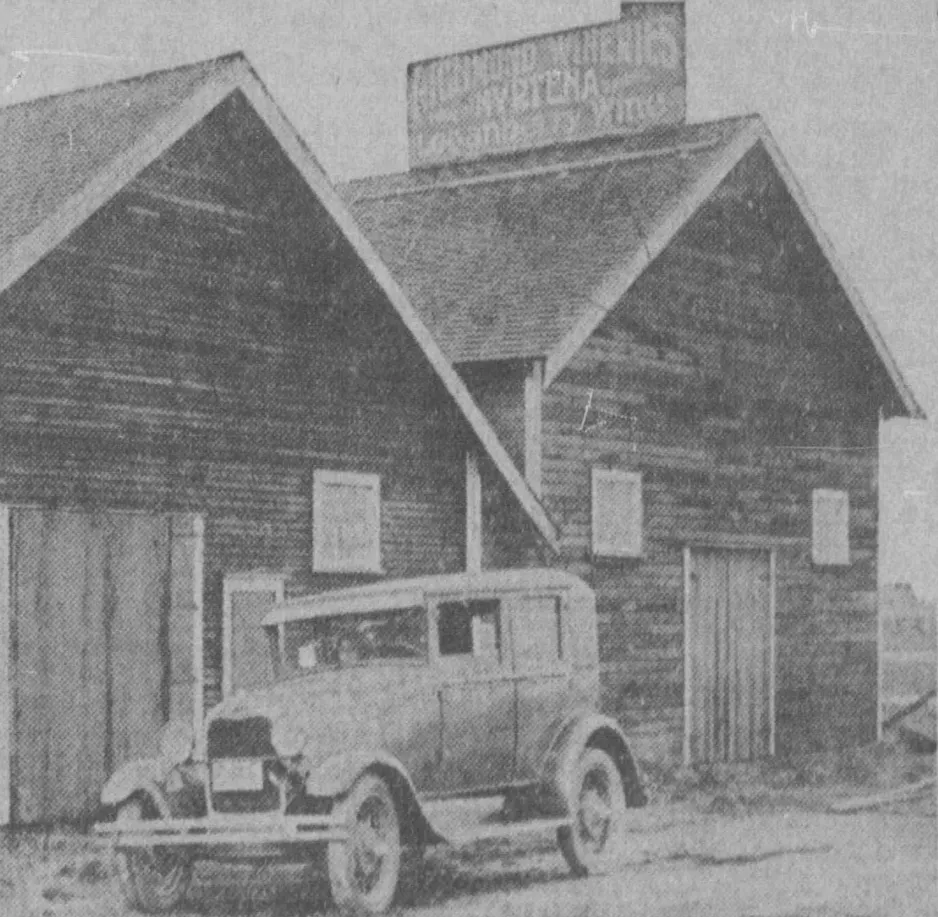

The humble abode of Richmond Wineries Limited, Steveston, British Columbia. Anon., “Lulu Island Firm Brings Fame To British Columbia By Its Manufacture of the ‘Myrtena’ Brand.” The Sunday Sun, 31 January 1931, 21.

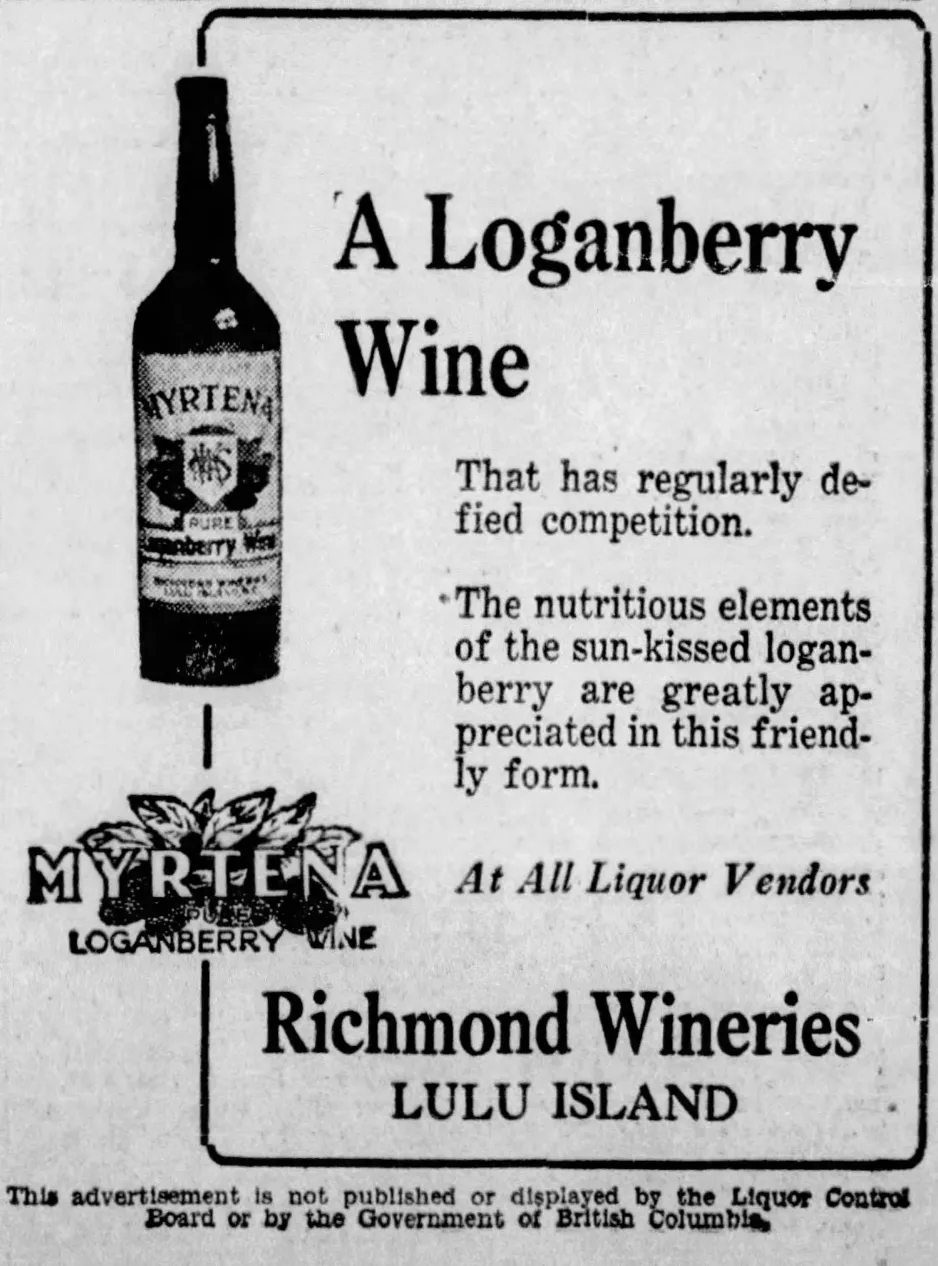

A typical advertisement issued by Richmond Wineries Limited of Steveston, British Columbia. Anon., “Richmond Wineries Limited.” The Vancouver Daily Province, 2 December 1933, 21.

Before too, too long, the loganberry wine produced in Steveston proved so popular that McKinney and Simpson had to buy the crops of several local growers just to keep up with demand.

Better yet, in 1931, they began to supervise the bottling of their product on site. And yes, this was done by hand until the installation of some bottling equipment during that same year.

By then, Richmond Wineries Limited of Steveston had made its appearance, which raises an interesting question: did some sort of Myrtena Wineries Incorporated / Limited / Registered officially exist before that point? Do you know, my reading friend, because yours truly does not?

In any event, Richmond Wineries was seemingly founded in 1926 or 1927, and…

Your doubtful air leads me to think that you doubt the quality of the popular loganberry wines produced by the aforementioned Growers Wine. Well, let me tell you, ye doubting Thomas / Thomasina, that French vintners on a visit to British Columbia during the summer of 1927 were far from displeased by the loganberry wines they tasted. Better yet, they were of the opinion that this inebriating beverage could secure bigger and more remunerative markets in Europe and Asia. So there.

Incidentally, Growers Wine seemingly took over Richmond Wineries in 1936 or 1937.

Over time, Growers Wine diversified its production, moving into grape wines as well as brandy as early as 1936, with the first bottles of grape wine coming out in 1939, I think.

Growers Wine changed hands several times between 1965 and 1986, possibly as a result of financial difficulties. Nowadays, it is known as Growers Cider Company of Niagara Falls, Ontario. I do not think that it still produces wine.

There were definitely other loganberry wine producers in British Columbia during the 1920s and 1930s – and quite possibly later. George W. Rathbun set up a winery in Richmond in 1927, for example. His facility burned down in November 1932, however.

You might be interested, or not, to learn that origin of the loganberry was the subject of some discussion among horticulturalists / botanists between the late 1910s and the late 1940s.

Several respected researchers, among them George McMillan Darrow, an American horticulturist employed by the United States Department of Agriculture, as well as Ulysses Prentiss Hedrick, an American botanist / horticulturist employed by the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, not to mention Albert Edward Longley, a Canadian American botanist / cytologist employed by the United States Department of Agriculture, believed that the loganberry was simply a variety of the California blackberry.

Other respected researchers, Liberty Hyde Bailey, a retired American horticulturist / rural life reformer, yes, the Bailey mentioned in the first part of this article, and Morley Benjamin Crane, an English botanist / horticulturalist employed by an English organisation, the John Innes Horticultural Institute, for example, stuck with the original assumption that the loganberry was a hybrid. They turned out to be right.

In Ucluelet, British Columbia, a renowned Scottish Canadian horticulturist / hybridiser, George Fraser, began to look into the mysterious pedigree of the loganberry as early as 1912. Sadly enough, yours truly has been unable to figure out where his research led.

Incidentally, the aforementioned Longley put aside his studies at Acadia University, in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, to start training as a pilot, around August 1918, in one of the Ontario schools of the Royal Air Force (Canada). The 11 November Armistice brought his military career to a close.

The aeroplane he trained on, or was about to train on, was of course the Curtiss JN-4 Canuck, a flying machine found in the exceptional collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario.

An interesting phase in the history of the loganberry in Canada began at some point in the mid to late 1930s. Eager to help his province, a businessman and Member of Parliament from Victoria, Robert Wellington Mayhew, managed to convince the powers that be to put loganberries and / or loganberry-based products on the food and / or drink menu(s) of the parliamentary restaurant, on Parliament Hill, in Ottawa.

By and large, the journalists, politicians and civil servants were rather impressed. With that success under its belt, Mayhew contacted several important hotels in Eastern Canada. The response was once gain generally favourable. As a result, wholesalers in that region of the country began to order loganberries and / or loganberry-based products.

The onset of the Second World War brought Mayhew’s efforts to a close. You see, the Royal Navy set out to absorb most of the British Columbian loganberry harvest in order to serve to its sailors a drink rich in vitamin C, to prevent scurvy. As a result, Eastern Canada wholesalers gradually ran out of loganberries and / or loganberry-based products.

When the conflict thankfully came to an end, in 1945, the loganberry growers lost their largest customer. Mayhew tried to help them but might not have met with much success. Mind you, the fact that he became Minister of Fisheries in Ottawa in June 1948 might have reduced the amount of time spent on promoting the loganberry.

A brief digression if I may. Would you believe that Mayhew’s spouse was named Grace Gertrude… Logan? I kid you not. Coincidences can be positively fascinating and utterly meaningless, but I digress.

As popular as it was during the first half of the 20th century, the loganberry gradually lost ground, and this despite the introduction of frozen loganberries.

As of 2024, it was not always easy to find that aggregate fruit in grocery stores, unless one lived in places like Oregon and, perhaps, British Columbia, I think.

This being said (typed?), loganberry plants remain quite popular with fruit gardeners, especially, perhaps, English fruit gardeners.

As well, loganberry juice appears to be quite popular in certain parts of New York, yes, the state, and Ontario.

And yes, several American microbreweries and at least a Canadian one have produced and / or continue to produce loganberry ales.

Interestingly, the loganberry gave birth to at least two cultivars. The staff of an English plant breeding and producing firm, Laxton Brothers Limited, for example, created the laxtonberry by crossing the loganberry with an English cultivar of raspberries known as the Superlative, and this no later than 1908. The aggregate fruit thus obtained was a darker shade of red.

The Santiam berry, on the other hand, was created by crossing the loganberry with the aforementioned California blackberry, one of the plants used to create that aggregate fruit. The Santiam berry was named after the Santiam River region of Oregon.

It has also been suggested that the loganberry played a role in the creation of the boysenberry, a deep maroon aggregate fruit developed in California around 1923 by an American horticulturist. Hurt in an accident and unable to commercialise his creation, a cross between the raspberry, loganberry, dewberry and blackberry, I think, Charles Rudolph Boysen all but abandoned it.

In the late 1920s, the aforementioned Darrow began searching for information about a large aggregate fruit which had been grown on the farm of a gentleman named Boysen. He got in touch with a California farmer / fruit expert, Walter Marvin Knott. The two men soon learned that Boysen had abandoned his experiments several years earlier and sold his farm.

Concerned yet hopeful, Darrow and Knott headed to the old Boysen farm, where they found several plants, barely alive in a field chockfull of weeds. Said plants were transplanted on Knott’s farm. The latter brought them back to health. As a result, Knott became the first person to grow boysenberries, a name given to the new aggregate fruit by Knott and / or Darrow.

Sadly enough, James Harvey Logan left this Earth around that that time, more specifically in July 1928. He was 86 years old.

And so our story ends.

Do not hesitate to come back next week to peruse the next issue of our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thingee.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)