Old bushplanes never die, they just fade away: A few lines, all right, many lines on the remarkable career of a Junkers Ju 52 “flying box car” named CF-ARM, part 1

May I begin this issue of our tremendous blog / bulletin / thingee with a heartfelt aeronautical hello? Yours truly would like to bring to you attention this week the remarkable career of an equally remarkable bushplane, the Junkers Ju 52 “flying box car” registered as CF-ARM of Canadian Airways Limited of Montréal, Québec.

And yes, I still very much intend to valiantly attempt to be briefer. So, let us begin.

Canadian Airways was created in November 1930, from the merger of Western Canada Airways Limited of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Aviation Corporation of Canada Limited of Montréal. The gentleman at the heart of that project was none other than James Armstrong Richardson, an influential businessperson based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and the father of Canadian commercial aviation according to some / many.

Over time, Canadian Airways became the largest privately owned air transport firm in Canada active between the two world wars.

And yes, the magnificent Junkers W 34 on display in the fantabulastic Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, carried / carries the colours of Canadian Airways, but back to our story.

At some points in 1931, the management of Canadian Airways was approached, separately it seemed, by its counterparts at the head of Hudson’s Bay Company of London, England, and Révillon Frères Trading Company Limited of Montréal, a subsidiary of Société Ancienne des Établissements Révillon Frères of Paris, France. These fur trading giants and competitors active in the icy regions of Northern Canada indicated they were planning to move hundreds of metric, Imperial and American tonnes of cargo in 1932 – by air.

As efficient as Canadian Airways’ fleet of bushplanes was, it might prove a tad insufficient for that awesome task, thought its managerial team. Therefore, the firm might well need to acquire a very large flying machine.

For some reason or other, Canadian Airways chose not to acquire a Ford 8-AT, a single-engine variant of the famous Ford Trimotor, a rugged, reliable and popular aircraft used in the United States and elsewhere, including Canada in the form of a Ford 6-AT Trimotor registered by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in May 1929.

Canadian Airways came to the conclusion that the recently developed Junkers Ju 52 would fulfil its cargo carrying requitement. And here lies a tale. A brief tale. Relax.

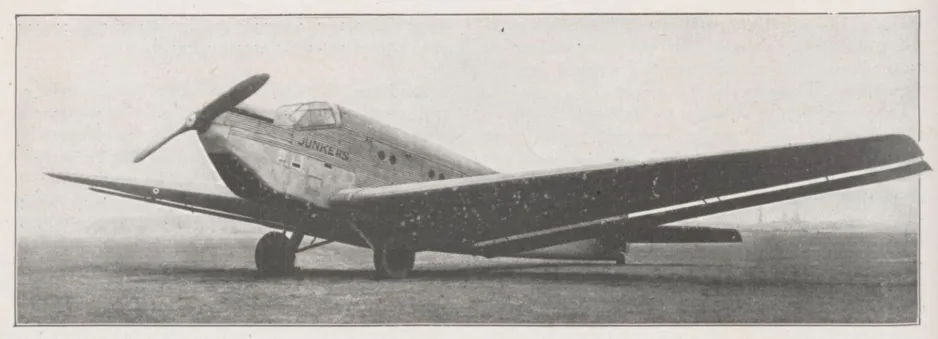

A Junkers Ju 52 at rest. Anon., “Un avion de fret long-courrier : Le Junkers Ju.52.” L’Aéronautique, March 1931. 124.

It so happened that the German aircraft manufacturer Junkers Flugzeugwerke Aktiengesellschaft, a firm mentioned in a March 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, had developed the Ju 52 for use as a cargo plane capable of carrying a sizeable load (2 200 kilogrammes (4 850 pounds) of freight) to and out of relatively short makeshift airfields. It could carry such a hefty load over a sizeable distance (900 kilometres (560 miles)) and at lower cost than any other flying machine of its day. Mind you, over shorter distances, the Ju 52 could carry up to 2 725 kilogrammes (about 6 000 pounds) of freight.

The Ju 52 could also be fitted with a pair of very large floats, which reduced the load it could carry quite significantly – by about 660 kilogrammes (about 1 450 pounds) if you must know.

Mind you, the aircraft included certain features requested by the German defence department, or Reichswehrministerium, for possible use by a future German air force. The term future was most appropriate given that the Treaty of Versailles, the piece of paper signed in late June 1919 which officially ended the First World War, a piece of paper imposed on Germany by the victors, expressly forbad that country from creating an air force.

The main side cargo hatch and one of the small cargo flaps of Canadian Airways’ Junkers Ju 52. CASM, 1183.

The end result was a flying machine with a huge cargo space accessible through a large cargo hatch on one side of the fuselage, a smaller cargo hatch on the other side and a large cargo hatch on top of said fuselage. There was also a side door and four small cargo flaps. On top of that, or was it on the bottom of that, the Ju 52 had a quarter of small cargo holds below the main cargo space, and a quarter of cargo flaps to access them. No other aircraft in the world had as many cargo hatches and flaps as the German giant.

The first Ju 52 flew in October 1930. As promising as its new aircraft was, Junkers Flugzeugwerke soon realised that the market for such a large cargo plane was quite limited. Indeed, only 6 of these machines were built. That, however, was by no means the end of the story. Nay.

You see, the German national air carrier, Deutsche Luft Hansa Aktiengesellschaft, had pressured the management of Junkers Flugzeugwerke into developing a trimotor version of the Ju 52 the latter had not been too keen to produce. The first example of that aircraft flew in March 1932. The Ju 52/3m, as the new version was called, proved rugged, reliable and popular with both civilian and military operators. Airlines in 30 or so countries on 4 continents (Africa, America, Asia and Europe) operated Ju 52/3ms until the 1950s. Air forces in close to 10 countries in Europe and America did the same, until the 1960s. And yes, the German machine was by far the most successful European airliner of the interwar period.

All in all, factories in Germany, France and Spain delivered approximately 4 850 Ju 52s, all versions included, between 1930 and 1952. As you may well imagine, most of these aircraft were delivered to the German air force, or Luftwaffe, both before and during the Second World War. Initially used as a bomber, the Ju 52/3m formed the backbone of the transport units of the Luftwaffe throughout the conflict.

And yes, the French-made aircraft were produced while France was occupied by National Socialist Germany, during the Second World War, and after the end of that occupation, but back to the Ju 52 operated by Canadian Airways.

Would you believe that this machine was the 6th and last Ju 52 operated as a single engine aircraft? Yea, it was.

A brief digression, if I may. After all, yours truly digresses so unfrequently. Did you know that Junkers Flugzeugwerke might, I repeat might, have considered the possibility of establishing some sort of assembly plant on Canadian (Québec?) soil in 1930? Yea, it did. A firm representative by the name of Richard Beier arrived in Montréal no later than July 1930 and talked to a number of people. In the end, the project, if there actually was one, fell through. As you may have guessed, it was one of the many aeronautical victims of the Great Depression.

This being said (typed?), Junkers Flugzeugwerke did set up a foothold in Montréal, Canadian Junkers Limited, in September 1930. Beier was its manager, but back to the Ju 52 operated by Canadian Airways. Again.

Incidentally, Canadian Junkers moved to Winnipeg at some point in the 1930s.

Even though the Ju 52 was, understandably enough, supposed to be fitted with a liquid-cooled Vee engine produced by Junkers Motorenbau Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, a sister / brother firm of Junkers Flugzeugwerke, another German aeroengine manufacturer got the contract. You see, Bayerische Motoren Werke Aktiengesellschaft offered an expense-paid trip to its factory to Thomas William “Tommy” Siers, the superintendent of maintenance of Canadian Airways, who was in Germany at the time. And no, I am not suggesting that anything untoward took place.

Incidentally, Canadian Airways paid the princely sum of $ 72 500 for its Ju 52, which corresponded to almost $ 1 350 000 in 2023 currency. The contract was signed and sealed (and delivered?) in early July.

Canadian Airways applied for a registration in September. The Civil Aviation Branch of the Department of National Defence, then responsible for civil aviation in Canada, granted the Ju 52 the registration CF-ARM. Actually, it also granted the aircraft the registration CF-ARZ. That mix-up was cleared in October when the Ju 52 officially became CF-ARM.

If one was to believe press reports of the time, Canadian Airways might, I repeat might, have planned to acquire a few additional Ju 52s if business warranted it. And yes, my news-hungry reading friend, Canadians newspapers published in most provinces of the country offered articles on the German giant to their readership. Aviation was indeed a cool topic in the early and mid 1930s.

Able to fly nonstop with a substantial load to almost any site under development in Northern Canada, the Ju 52 was seen by many as the start of a new chapter in the development of the transport system of that huge region of the country.

The aforementioned Richardson, who happened to be president and general manager of Canadian Airways, hoped that the Ju 52 would be of great help in opening up northern Canada and that it would play a big role in giving Canada the best air transport system possible.

Would you believe that, in theory, the Ju 52 could have flown non stop from London, England, to Cairo, Egypt, a distance of about 3 500 kilometres (about 2 175 miles), with 500 kilogrammes (1 100 pounds) on freight on board – and several extra fuel tanks mounted on board for such an odyssey?

In any event, the Ju 52 was crated and sent to Montréal aboard the SS Beaverbrae, a cargo liner / passenger cargo ship operated by Canadian Pacific Steamships Ocean Services Limited, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway Company of Montréal, a Canadian transport giant mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since April 2018. It got there in October 1931. Its European departure point was apparently the harbour of Hamburg, Germany.

Incidentally, did you know that the SS Beaverbrae was the ship which carried a world famous Supermarine S.6B racing floatplane of the Royal Air Force’s High Speed Flight back to England, from Montréal to London, back to the Science Museum in London, England, more specifically, in October 1932?

You see, that aircraft had come to Canada earlier in the year. It was displayed in late August and early September at the 1932 edition of the Canadian National Exhibition, in Toronto, Ontario, before going on display in October, for 10 days, at the famous James A. Ogilvy’s Limited department store in Montréal.

Interestingly, the presence of the S.6B in Montréal was not part of the original plan. The Science Museum chose to graciously acquiesce to sustained requests from Montréal aviation enthusiasts that the aircraft be displayed in the metropolis of Canada.

The pilot of the S.6B in question, Flight Lieutenant John Nelson Boothman, had won the 1931 edition of the world famous Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider, held in England in mid September. The aircraft displayed in Montréal was not, however, the S.6B which had broken the world speed record by reaching a peak speed of almost 657 kilometres/hour (almost 408 miles/hour) in late September 1931. Nay.

And yes, the 3 floatplanes of the High Speed Flight were the only aircraft which took part in the 1931 edition of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider, but back to our story.

The Ju 52 may, I repeat may, have been sent across the Saint Lawrence River by barge in order to be assembled by employees of a well known Canadian aircraft manufacturer, Fairchild Aircraft Limited of Longueuil, Québec – a subsidiary of the American aircraft manufacturer Fairchild Aviation Corporation mentioned in several / many issues of our amaazing blog / bulletin / thingee since August 2018.

CF-ARM, which happened to be the largest aircraft in Canada, first took to the sky in Canada in Longueuil in late November 1931. It flew to the nearby airport at Saint-Hubert, Québec, that same day. Employees of Canadian Junkers examined the aircraft before handing it to employees of Canadian Airways. While at Saint-Hubert, the Ju 52 performed several demonstration flights with varying payloads in front of a large crowd which included a number of very important people.

In late, late November, a Canadian Airways crew flew the Ju 52 to RCAF Station Rockcliffe, near Ottawa, which happened to be a stone throw from the site occupied in 2023 by the staggering Canada Aviation and Space Museum. While at Rockcliffe, the aircraft was examined by a number of very important people, and…

What is it, my perplexed reading friend? Were you expecting to see the names of the very important people? You do remember that I still very much intend to valiantly attempt to be briefer, do you not? But I digress and…

You are freaking me out. What are you doing? You are going to hold your breath until I provide you with some names? A list is just a list. Now stop it! Okay, okay! Here are a few names:

- Wing Commander Lloyd Samuel Breadner, Director of the RCAF,

- George Joseph Desbarats, Deputy Minister of National Defence,

- Major General Andrew George Latta McNaughton, Chief of the General Staff of the Canadian Army, and

- John Hamilton Parkin, Assistant Director of the Division of Physics of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC).

These gentlemen examined the Ju 52 at RCAF Station Rockcliffe. And yes, McNaughton was mentioned in an October 2020 issue of our stunning blog / bulletin / thingee. NRC, on the other hand, was mentioned many times, and that since May 2018.

A gentleman present at Saint-Hubert, on the other hand, was none other than the President of Curtiss-Reid Aircraft Company Limited of Cartierville, Québec, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, a gentleman mentioned many times in that same blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2017. You know of course that Curtiss-Reid Aircraft was mentioned therein in March 2019 and March 2021, but back to our story.

The crew of CF-ARM flew from RCAF Station Rockcliffe to an airfield in Toronto in early December. It left a couple of days later and stopped for not too long a time in Hamilton, Ontario. A blizzard had prevented the crew from landing for some time. It circled the airfield until things calmed down.

The final destination of the crew and aircraft was Winnipeg. To simplify things, they followed a route travelled by many crews and aircraft before and after them. In other words, they crossed into the United States and, more specifically, flew to Detroit, Michigan.

While there, the Canadian Airways team was able to compare the Ju 52 with the one and only Ford 8-AT, a single-engine variant of the famous Ford Trimotor, a rugged, reliable and popular aircraft mentioned above. All in all, the German machine seemed superior to the American one.

Stuck in Detroit for a few days because of bad weather, the crew of the Ju 52 flew to St. Paul, Minnesota, as planned. During the flight from that fine city to Fargo, North Dakota, the crew was faced with an emergency: the carburettor of the BMW VII engine caught fire near the Minnesota-North Dakota border. The minor conflagration was partly extinguished before the aircraft made an emergency landing at Fergus Falls, Minnesota.

And yes, you are quite right, my cinephile reading friend, Fargo was / is the location where the very good 1996 American motion picture Fargo was not filmed, even though the script of that black comedy crime film was taking place in, well, Fargo. Anyway, let us move on.

Assisted by people at Fergus Falls, the crew of the Ju 52 made some temporary repairs. Two or three days after alighting there, the aircraft and its crew took to the sky. The flight to, not, not Fargo. The flight to Pembina, North Dakota, was interrupted by some problem or other not too long after takeoff. CF-ARM and its humans returned to Fergus Falls. More temporary repairs were made.

As CF-ARM taxied at low speed prior to takeoff, the rear end of the rear fuselage collapsed. A quick look revealed that the metal part which attached the aircraft’s tailwheel to the rest of the fuselage had sheared right off. More repair work was made. The Ju 52 and its crew made it to Pembina without a hitch.

The following morning, which was seemingly pretty cold, the engine stubbornly refused to start. Hot oil and water had to be poured in its lubrication and cooling systems. Better yet, the engine itself had to be warmed up. CF-ARM and its crew flew from Pembina to Winnipeg later that day. By then, it was late December. The journey between RCAF Station Rockcliffe and the Manitoban capital had taken about three and a half weeks.

One had to wonder if the aforementioned Richardson and Siers were amused.

Do you have a question, my reading friend? Given the frigid temperatures in Canada’s northern regions, might an air-cooled engine have been preferable? After all, while it was true that the water in the radiator of the BMW VII could freeze solid at night if left unprotected, the oxygen and nitrogen in our atmosphere will turn into solids only at -219 and -210 degrees Celsius (-362 and -346 degrees Fahrenheit), temperatures one was unlikely to encounter even at the North Pole, or the South Pole, or in Ottawa.

You raise a good point, my weather wise reading friend. The truth is that I cannot say why a liquid cooled engine was chosen. This being said (typed?), a combination of power, cost and availability was quite likely, but back to our story.

And this is as good a time as any to end this first part of our article on the remarkable career of the equally remarkable Ju 52 of Canadian Airways.

See ya next week.

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)