“Fakes that pay off:” A brief glance at the totally fictitious nuclear-powered Soviet super bomber ‘revealed’ in December 1958 by the American magazine Aviation Week, Part 3

Hail, my reading friend. I dare to hope that all was well with you. Countless people out there would like to be in your shoes, or mine.

Would you like to start reading the 3rd and final part of our story concerning the totally fictitious Soviet nuclear-powered super bomber ‘revealed’ in December 1958 by the American magazine Aviation Week? Wunderbar!

A brief digression before going further, if I may. By early April 1959, Aurora Plastics Corporation had released a plastic kit known as the Russian Nuclear Powered Bomber.

That American manufacturer of plastic objects founded in 1950 marketed its first scale model, an aircraft, in 1952. Often criticised for the quality of its scale models, that great name in American if not global model making was nevertheless among the most innovative.

The magnificent illustration on the box of the model, an illustration which showed the Soviet aircraft and the famous Krasnaya ploshchad, in English red square, in the heart of Moskvá / Moscow, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), was among the hundreds of works of the Polish-American aviation artist Józef “Jo” Kotula, one of the co-founders of the American Society of Aviation Artists.

For some reason or other, the Russian Nuclear Powered Bomber was not favoured by modelers. Sales were so bad that Aurora Plastics did not produce a second batch once the first one ran out. Indeed, the American firm shipped the molds to Playcraft Toys Limited, an English toy manufacturer with which it was associated. That transfer took place around 1962. History does not say whether the Russian Nuclear Powered Bomber was successful in the United Kingdom.

By the way, at the end of 1958, Aurora Plastics had offered its customers a scale model of the Canadian Avro CF-105 Arrow supersonic all-weather fighter. As you probably know, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, has in its very, very high quality collection the largest elements of that iconic aircraft which survived its cancellation, in February 1959.

A Russian Nuclear Powered Bomber in perfect condition in its box will sell for a lot of dough in 2024, by the way.

And the real Soviet nuclear aircraft program in all this, the one which was not mentioned in the early parts of this article, what did it look like, you ask, my reading friend? A good question.

Would you believe that the aircraft in the Aviation Week magazine article at the heart of this article bears a striking resemblance to the Myasishchev M-50, the Soviet supersonic strategic bomber in the photograph above, the prototype of which was completed in the fall of 1958, more or less at the time when the aircraft in the Aviation Week article made its first flight, at least according to that magazine?

This M-50 was obviously a top-secret machine, hence the following question: how the h*ll did Aviation Week manage to get its hands on one or a few photographs or drawings of that aircraft? And why did that magazine come to think that it was linked to the Soviet nuclear aircraft program?

Certain details in the article suggested that the editor and publisher of Aviation Week, Robert B. Hotz, had access to secret information that the well-informed Office of National Estimates had used to create a National Intelligence Estimate submitted more 3 weeks after publication of the article.

Said secret information might also have come from a Central Intelligence Bulletin dating from September 1958. The information contained in that bulletin read as follows:

The aircraft sighted on a Moscow factory airfield on 7 August appears to be a modified delta-wing four-jet bomber. Performance data for this prototype has not yet been determined, but its design suggests that it may be capable of supersonic flight.

The committee which assigned code names to new aircraft in the Soviet bloc, the Air Standards Coordination Committee, appeared to name this machine Bounder no later than early November 1958.

Mind you, Aviation Week might also have had access to at least some elements of a Technical Briefing for Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion Office Representatives on November 7 and 8, 1958 prepared by the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion Department of the Atomic Products Division of General Electric Company.

That document of more than 300 pages (!) contained a top and profile view of a Soviet nuclear-powered aircraft which bore the name… Bounder. Those views bear a striking resemblance to those published by Aviation Week in December 1958.

The person or persons who provided information to Hotz, completely illegally of course, have never been identified, at least not publicly.

The Soviet nuclear aircraft program apparently originated from an August 1952 memo in which a prominent Soviet physicist and deputy director of the Institut atomnoy energii, Anatoly Petrovich Alexandrov, suggested to another prominent Soviet physicist and father of his country’s nuclear weapons program, Igor Vasil’yevich “Boroda” Kurchatov, that the existing knowledge on nuclear reactors raised the possibility of adapting that technology to the world of aeronautics.

Since the USSR was then seen by the governments of the United States and its allies as an evil empire, you might be surprised to learn that, initially, the Soviet government did not wish to embark on that adventure, judging that it would be too complex, costly and time-consuming (15 years? 20 years??).

This being said (typed?), said government might have financed the construction of a full-size mock-up of a hypothetical nuclear-powered bomber between 1952 and 1955.

It finally took the plunge in 1955.

In August, the experimental design bureau headed by Vladimir Mikhailovich Myasishchev received the order to begin the design of a nuclear-powered supersonic strategic bomber. The configuration of that aircraft equipped with direct cycle nuclear engines, the Myasishchev M-60, changed several times. The one adopted at the end of 1957 perhaps closely resembled the M-50.

Indeed, Myasishchev at one point considered placing a small nuclear reactor aboard an M-50, thereby transforming that machine into a flying test bed.

By the way, an early configuration of the M-60 bore a striking resemblance to that of the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, a supersonic fighter aircraft represented in the exceptional collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, but I digress.

The engineers of the Myasishchev experimental design bureau knew only too well how difficult developing a nuclear-powered supersonic strategic bomber would be.

For example, it would be necessary to design a radiation-proof capsule for the crew which would be equipped with periscopes, radar screens and television screens thanks to which said crew would have a view of the outside world, a very limited view however. The cabin would obviously contain an air supply system without any external input, the outside air being too radioactive.

It would also be necessary to design a fully automatic flight control system which would control the aircraft from takeoff to landing, a system so advanced that one wonders what purpose the crew would serve, which reminded yours truly of an old pilot joke about cockpit automation according to which the ideal crew would be a pilot and a dog. The pilot would be there to feed the dog, and the dog would be there to bite the pilot if he tried to touch the controls. Sorry, sorry. Let us return to the problems inherent in the use of nuclear engines on an aircraft.

It would also be necessary to design new metal alloys capable of resisting the intense heat and radiation emanating from said engines.

As well, it would be necessary to develop completely new methods of ground maintenance, or even completely new air bases. In fact, all maintenance would have to be done remotely using remote-controlled devices.

In fact, again, Soviet studies suggested that the radiation emanating from the nuclear engines of the new bomber would be so high that it would become possible to approach it only 2 or 3 months after each flight. I kid you not.

And let us not forget the safety problems caused by the slightest accident, or incident.

Yours truly also wonders how the crews of those aircraft would have accessed and left them without being fatally irradiated. Anyway, let us move on.

Before I forget it, one of the American aircraft manufacturers working on a nuclear-powered strategic bomber project, an aircraft manufacturer mentioned in August 2018, July 2020 and January 2022 issues of our perennial blog / bulletin / thingee, the Convair Division of General Dynamics Corporation, studied the radiation present in the very hot air leaving the reactors of a hypothetical bomber of that type. The name given to that initiative from the 1950s denoted a certain sense of humor.

You see, said name was Project Halitosis, in other words project foul breath.

Along the same lines, people high up in the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program (seriously?) proposed that the crew members of United States Air Force nuclear-powered strategic bombers be of an age beyond the age at which such people usually had children. The mind boggles.

By the way, an American engineer involved in the ANP program published a slightly nasty science fiction novel called Steam Bird in 1988. Hilbert van Nydeck Schenck, Junior, described what happened when an American nuclear-powered strategic bomber went on a mission during a political crisis. While the flight itself went rather well, the return to the ground of that radioactive mastodon caused serious headaches for everyone involved.

For some reason, the novel’s cover artist drew inspiration from the British Handley Page Victor strategic jet bomber to create his fictitious bomber, but back to our atoms.

Before I forget, and you thought I had, did you not, my reading friend, General Dynamics was mentioned many times in our superb blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2018. Its Convair Division, on the other hand, was so blessed in August 2018, July 2020 and January 2022 issues.

The Myasishchev experimental design bureau seemingly more or less abandoned the M-60 around 1958. It then began the development of an even more impressive supersonic nuclear-powered strategic bomber, the Myasishchev M-30, equipped with 6 indirect cycle nuclear engines.

That project itself was more or less abandoned when said experimental design bureau received the order to cooperate in the development of a long range missile designed by the experimental design bureau headed by Vladimir Nikolayevich Chelomei.

The M-50, you remember it, do you not, flew for the first time in October 1959. Its disappointing performance, caused in large part by the failure of the powerful turbojet engine designed specifically for it, as well as the entry into service of the first Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile, in December 1959, meant that this aircraft was not series produced.

Indeed, it was in December 1959 that the most important nogoodnik in the USSR, the first secretary of the Kommunisticheskaya Partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza, Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, a nogoodnik mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since February 2019, created the Raketnyye voyska strategicheskogo naznacheniya SSSR, in other words the strategic missile forces of the USSR.

Khrushchev indeed believed that intercontinental ballistic missiles were far superior to bombers. He was going to give the former money hand over fist and starve of cash the latter.

Engineers from the Myasishchev experimental design bureau might, I repeat might, however, have prepared, around 1960, sketches of systems allowing hypothetical production M-50s to take to the air if strategic bombers or intercontinental ballistic missiles of the United States Air Force managed to damage or destroy their bases.

M-50s equipped with booster rocket engines could thus take off using ginormous multi-wheeled vehicles, or even equally ginormous floats supporting their fuselage and smaller floats supporting the turbojet engines at the wingtips. Yes, yes, floats floating on the water. I kid you not.

Those projects, assuming they existed, led nowhere.

It was probably out of fear of such American attacks that engineers from the Myasishchev experimental design bureau prepared plans for a nuclear-powered strategic bombing flying boat, the Myasishchev M-60M. That project went nowhere.

The Myasishchev experimental design bureau just could not catch a break.

Worse still, it became a simple division of the Chelomei experimental design bureau in October 1960. Myasishchev, for his part, rose to the position of director of the Soviet central aerohydrodynamic institute, the Tsentral’nyy Aerogidrodinamicheskiy Institut, which was not really bad at all.

This being said (typed?), the Soviet authorities decided to fly the M-50 during the major air show of the Den’ Vozdushnogo Flota, in English day of the air fleet, which took place at the Túshinskiy aerodrom, not far from Moscow, in July 1961. They perhaps wished to make American and other Western country observers believe that the entry into service of that machine was still being considered.

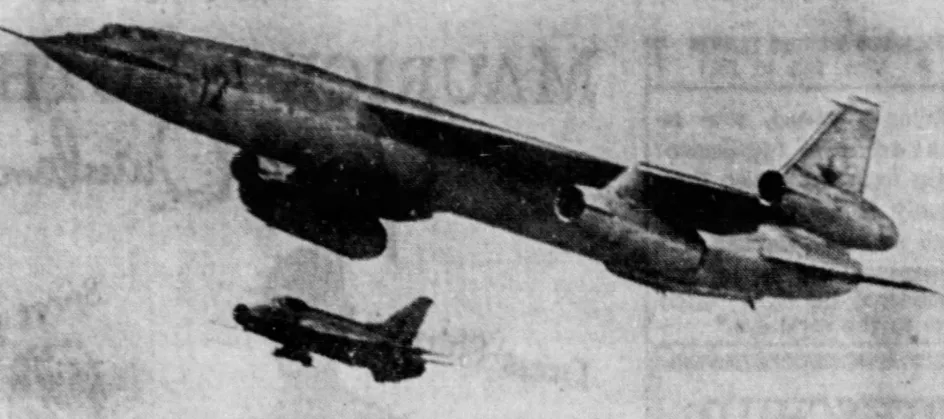

That spectacular flight, the very last carried out by the M-50 it seemed, certainly did not go unnoticed. The aircraft was then escorted by a duo of Mikoyan-Gurevitch MiG-21 supersonic fighters.

And yes, the photograph at the beginning of this 3rd part of our article showed the M-50 and one of the MiG-21s which flew alongside it.

Interestingly, some Western observers wondered if the M-50 could inspire the development of a supersonic airliner for the Soviet civilian state air carrier. The big boss of Aeroflot, Aviation Colonel General Evgeny Fedorovich Loginov, however, told at least one American journalist, as early as July 1961, that the sustained supersonic flights that such an aircraft would carry out required the development of an original machine designed for that purpose.

Thus ended the Soviet nuclear aircraft program. Well, almost. You see, the decision taken in August 1955 to design that type of aircraft also concerned the experimental design bureau headed by Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev, a giant of the Soviet aeronautical industry mentioned in February 2018 and March 2019 issues of our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thing.

The first flight of the American Convair B-36 strategic bomber carrying a small nuclear reactor, in September 1955, I think, a flight which took place in secrecy, disrupted the engineers’ long term plans. Reports to that effect actually arrived in the USSR in December, in all likelihood following the publication of articles in American daily newspapers at the very beginning of the month.

In March 1956, the Tupolev experimental design bureau received the order to design and manufacture a flying test bed capable of transporting a small nuclear reactor. Its engineers oversaw the conversion of a Tupolev Tu-95 turboprop strategic bomber. That Letayushchaya atomnaya laboratoriya, in English flying atomic laboratory, flew for the first time in May 1961. The aircraft and its reactor seemed to be satisfactory.

Engineers from the Tupolev experimental design bureau also prepared sketches of several attack, strategic bombing and maritime reconnaissance / antisubmarine aircraft during the 1960s and 1970s, but none of them came to fruition.

The same went for the proposed nuclear-powered maritime reconnaissance / antisubmarine aircraft derived from the Soviet Antonov An-22 Antei turboprop heavy transport aircraft dating from the 1970s. This being said (typed?), an An-22 carrying a small nuclear reactor strolled through the skies from the fall of 1972 onward. That aircraft was scrapped on an undetermined date.

The Soviet flying atomic laboratory, for its part, suffered the same fate towards the end of the 1980s.

The Myasishchev M-50 on display in the open air, at the mercy of the elements, on the site of the Tsentral’nyy muzey Voyenno-vozdushnykh sil, Mónino, Russia, August 2012. Alan Wilson via Wikipedia.

The M-50, finally, is among the many aircraft exhibited outside, at the mercy of the elements, on the site of the Tsentral’nyy muzey Voyenno-vozdushnykh sil, in English central museum of the air force, in Mónino, Russia, not far from Moscow.

And that is all for today.

For many, Aviation Week, subsequently Aviation Week and Space Technology, is the bulletin board for the American military industrial community. For others, it is sometimes / often a peddler of more or less eccentric stories, which explained the nicknames given to that magazine, either AvLeaks or Aviation Leaks and Space Follies / Mythology.

One only needs to mention the articles dating from the early 1990s on the American stealth reconnaissance aircraft Northrop TR-3 Black Manta, or those from the mid-2000s on the Blackstar, an American dynamic duo consisting of a small vehicle capable of going into space and a large carrier aircraft which took it to a very high altitude. The Blackstar was just as fictitious as the Black Manta, I think.

Have a good week, my reading friend, and be careful in your readings. Well, with the exception of the present one. Of course.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)