The tale of the most extraordinary photographs ever taken of air fights during the First World War, Or, The long and short of the Cockburn-Lange collection

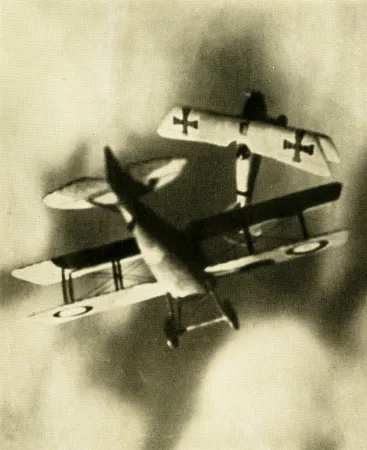

Hello, old bean / chap. Fancy a trip in your crate today? If so, yours truly has a mildly interesting story for you. And yes, you are indeed quite right, my astute reading friend. The photograph above was also published in the November-December 1932 issue of the Chilean magazine Chile Aéreo, in an article entitled “Fotographias auténticas de los combates aéreos.” You did not know that the breathtaking library of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, had issues of Latin American aviation magazines dating from the 1930s, now did you? Well, it does, but back to our story.

One might argue that said story began in late 1930 or early 1931 with the arrival in the United States of a unique collection of thrilling First World War aerial combat photographs taken in mid air, a court martial (?) offense against the humorously-named Defence of the Realm Act of 1914, or DORA, by an unnamed Royal Flying Corps (RFC) / Royal Air Force (RAF) fighter pilot who had not lived to see the signing of the Armistice, in November 1918.

That pilot having come across a small German camera mounted on a shot down German airplane, he thought it would be a good idea to mount it on his own machine.

The collection of photographs belonged to the spouse of Richard W. Cockburn-Lange, Gladys Maud Cockburn-Lange, the remarried widow of the pilot in question, an ace with more than 12 aerial victories to his credit. The collection consisted of several hundred photographs, of which only 55 or so actually showed aircraft of the RFC / RAF, Aéronautique militaire and / or of Luftstreitkräfte, the air service of the Deutsches Heer. Adding to the collection’s importance was the fact that the unnamed pilot had jotted down a brief description of each of the aerial combats portrayed in the photographs.

The (partial?) description of the aerial combat portrayed in the photograph you saw above, my reading friend, read / reads as follows:

Ran into a tangle of Spads and Albatross [sic] this morning. We were right above the clouds and as soon as the Fritzies saw us they dived into the clouds and were lost. I took a pot shot at one and missed but, to my surprise back at the drome, I found I had a pretty good picture.

First seen in public in a free international exhibition of aviation material (paintings, photographs, prints, etc.) inaugurated in February 1931 by the well-known American publishing house G.P. Putnam’s Sons Incorporated, as well as by The New York Times, the images of the Cockburn-Lange collection were arguably the hit of the show, and…

You have a question, my reading friend? Why was identity of the pilot kept hidden, you ask? He had acted against regulation, yes, but he was also, err, dead. Well, you see, another pilot, presumably a good friend, had known about the small camera mounted on the unnamed pilot’s fighter plane. That individual was still serving in the RAF in the early 1930s and could have found himself in an awkward position had the name of his deceased friend been revealed.

Would you believe that the monthly magazine Canadian Aviation began to publish images of the Cockburn-Lange collection in 1932, the first one being the photograph above, published in the January issue of that publication? It is quite possible, if not likely, that the decision to do so was taken by the owner of the magazine, the Aviation League of Canada, an organisation based in Toronto, Ontario, which was affiliated with a British organisation, the Air League of the British Empire. Incidentally, while the former pretty much ceased to operate after 1932, the latter was still ticking along in 2022. Nowadays, however, it is known as the Air League, the word empire sticking in the craw of countless people whose lands had been pillaged / invaded / exploited by the United Kingdom.

One only needs to think about the Benin bronzes, taken / stolen during the sack of the capital of the African kingdom of Benin, in 1897, or the Parthenon marbles, taken / stolen from the site of the Parthenon, in Athens, Greece, by the British ambassador to the Ottoman empire, between 1801 and 1812. Dare I say (type?) that we should count on the British Museum to do the right thing – after it has tried everything else? Too offensive? All right, I will not dare.

As you may well imagine, Canadian Aviation was by no means the only magazine to publish photographs from the Cockburn-Lange collection. A famous British weekly magazine published a trio of images in October 1932. Whether or not Illustrated London News offered more photographs to its readers later on is unclear. Sunday Pictorial, a brother / sister publication of a famous London newspaper, The Daily Mirror, did one better. It published an 11-part serial based on the Cockburn-Lange collection.

Mrs. Cockburn-Lange made a fair amount of moolah out of these deals.

She also happily sold copies of her precious images, the greatest images of aerial combat of the first World War if not of all times, to members of the British elite and First World War aviators. She did all of her business through third parties, however. Mrs. Cockburn-Lange seemingly liked her privacy. She liked it so much that she pretty much disappeared around the mid 1930s.

Although out of the limelight, Mrs. Cockburn-Lange was probably enjoying a good life. You see, the year 1933 had seen the publication, in London, England, of a book entitled Death in the Air: The War Diary and Photographs of a Flying Corps Pilot. That work sold very well. A second printing came out in 1936. Mrs. Cockburn-Lange may have received up to $ 20 000 from the publisher, a sum equivalent to more than $ 400 000 in 2022 currency.

A great story, you say (type?), my reading friend? Well, it certainly was.

This being said (typed?), the absence of certain elements (squadron numbers, place names, last names of individuals, specific dates, etc.) in what was for all intent and purposes an edited diary was deemed perplexing by several people.

Several people were also puzzled by certain aspects of the Cockburn-Lange photographs themselves. Someone wondered, for example, how the unnamed pilot could have taken photographs of British or French airplanes given that the shutter of his camera was controlled by the mechanism which activated his machine gun(s). A second someone wondered how the wheels of all the airplanes photographed could be clean given that both the Allied and German air forces operated from all too often muddy airfields.

Such piffles were pretty much ignored. The photographs were simply too impressive to ignore.

If I may show a hint of impertinence, my reading friend, that very impressiveness might (should?) have rung some bells. Indeed, photography experts at Time-Life Incorporated, the book marketing division of American magazine publishing giant Time Incorporated, stated in 1979 that the Cockburn-Lange photographs they had examined were fakes.

A renowned photograph analyst had come to the same conclusion at some point in the early to mid 1950s. How else could one explain that none of the 14 (!) airplanes shown in various flight attitudes on a single photograph was out of focus? That photograph analyst had looked at the images in question at the request of historians of the United States Air Force Technical Museum / United States Air Force Museum.

The photograph analyst in question was none other than Arthur Charles “Art” Lundahl, (founding?) head of the United States Navy’s Naval Photographic Interpretation Center until 1953 and, from that date onward, founding head of the Photographic Interpretation Division (PID) of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

And yes, photograph analysts of the CIA’s PID were the good folks who found visual evidence of Soviet thermonuclear-tipped medium range ballistic missiles in Cuba, in October 1962, a discovery which triggered the Cuban missile crisis, a crisis which came too darn close for comfort to initiating a third world war.

Would you believe that a similar conclusion of fakery had been reached no later than 1932 by Charles Grey “C.G.” Grey, the founding editor of the famous British weekly The Aeroplane, a contradictory individual who could be supremely offensive yet supremely generous? Well, you should.

A somewhat memorable statement made by Grey around 1940-41 reads as follows:

We quite agree […] that there are millions of women in the country who could do useful jobs in war. But the trouble is that so many of them insist on wanting to do jobs which they are quite incapable of doing. The menace is the woman who thinks that she ought to be flying in a high-speed bomber when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly, or who wants to nose around as an Air Raid Warden and yet can’t cook her husband’s dinner.

Wow.

Grey noted that all of the airplanes in the photographs had entered service in the late summer of 1917, just 15 or months before the Armistice. Given that the unnamed aviator’s camera seemingly took only one photograph per flight, given also that individual’s admission that he was a poor photographer, Grey stated that said aviator had to be exceptionally lucky and would have needed to fly an exceptional number of missions to take the hundreds of photographs in the collection.

Grey was sufficiently troubled to create a fake image of his own to buttress his theory that the Cockburn-Lange photographs were not authentic.

Incidentally, around that time, for some reason or other, both the RAF and the Imperial War Museum politely declined to purchase copies of the Cockburn-Lange photographs until their authenticity could be proven.

Let us now put on the seven-year boots which will allow us to bridge the period between the mid 1930s and the year 1984. Seven strides should do it. Ready? Let us stride.

In 1984, an elderly gentleman by the name of John W. Charlton donated several trunks to the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, District of Columbia. Said trunks were chock full of First World War material: uniforms, photographs, maps, documents, etc. There was also a damaged semi-automatic pistol. Some of the photographs were originals from, you guessed it, the famous Cockburn-Lange collection.

Peter Grosz, a German American engineer and world-renowned expert on German aircraft of the First World War, and Karl S. Schneide, a curatorial assistant / assistant curator at the National Air and Space Museum, were able to trace the material to an American gentleman by the name of Wesley David “Wes” Archer who was originally trained and educated for the ministry. Born in 1892, Archer served as a pilot in the RFC / RAF in 1917-18. Indeed, he was shot down not too long before the end of the First World War. A German bullet would have hit Archer’s heart had it not been stopped by his semi-automatic pistol. Yes, my reading friend, that pistol, the one mentioned in the previous paragraph. The young American might have been in hospital when the Armistice was signed.

Would you believe that Archer may have piloted 2 types of fighter planes present in the absolutely fabulous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum? Well, he may indeed. The aircraft in question were / are the Nieuport Ni 17 and the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5. It should be noted that the former is a replica.

Wesley David “Wes” Archer. Anon., “Says Three Months in St. Petersburg Is Worth All the Medicine and Tonics.” St. Petersburg Times, 8 December 1925, 18.

After the conflict, Archer directed several now forgotten movies in the United States and, perhaps, in the United Kingdom, Germany and France but that career did not proceed as well as expected. He later designed dioramas. Archer found his true calling, however, when he began to make model airplanes, mainly for the movie industry, but back to our story.

Grosz and Schneide came across photographs Archer had taken during the First World War, as well as photographs showing him in the process of making model airplanes. In other words, nothing out of the ordinary. Their jaws fell, however, when they fell upon photographs of aerial battles in which support wires could be seen.

Yes, my reading friend! The airplanes portrayed in the world-famous Cockburn-Lange collection were in fact models made and photographed by Archer. The Cockburn-Lange collection was a fake, as were the brief descriptions of aerial battles which accompanied it. (Dramatic music.)

And yes, you are correct, my perspicacious reading friend. It is indeed possible that certain elements within the descriptions accurately describe aerial battles in which Archer and / or a friend were involved. Chances are that we will never know for sure.

Further research showed that Mrs. Cockburn-Lange was none other than Archer’s spouse, England born Gladys Maud “Betty” Archer, born Garrett. The pair had met in the United Kingdom during the First World War, when Garrett served in the Women’s Royal Air Force.

Mr. and Mrs. Archer had fooled the aviation community and media on both sides of the Atlantic.

Why did they do it, you ask? Well, the Great Depression was a terrible time. Archer needed to put food on the table and keep a roof over his head and that of his spouse. Given his talent as a model maker, he gradually came to the conclusion that he could make moolah selling faked photographs of aerial battles.

Let us not forget that aviation was a hot commodity in the late 1920s and early 1930s. While the First World War itself was seen as a mindless bloodbath, wartime aviators, mainly fighter pilots actually, were seen as knights of the air. Fictitious fighter pilots proved irresistible to movie audiences of the time.

Wings, a 1927 American silent film, won the very first prize for best film awarded by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in 1929. One of its American stars, Richard Arlen, born Sylvanus Richard “Van” Mattimore (?), learned how to fly in a Royal Air Force school, yes, a British school, installed in Ontario during the First World War, but did not take part in any air combat, as a result of the signing of the Armistice.

On another note, a wealthy American pilot and businessman, Howard Robard Hughes, Junior, an individual mentioned in several / many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2018, spent considerable sums of money to ensure the success of his 1930 blockbuster Hell’s Angels. In fact, he ordered that a great many scenes already completed be reshot to transform the existing film into a talking film, and a very successful one it proved to be.

It should be noted that the Fokker D.VII and Sopwith 7F.1 Snipe fighter planes of the wondrous Canada Aviation and Space Museum appeared / appear, in flight or on the ground, in at least one scene of Hell’s Angels, but back to our story.

A digression if I may. Many years ago, yours truly mentioned to the director general of the museum that it might not be a bad idea to restore the D.VII the way it looked during the filming of Hell’s Angels. (Hello, sir!) I seem to recall he was noncommittal but neither did he say that I was muy loco en la cabeza. (Thank you, sir.)

Don’t you think a that bright red D.VII would have looked just spectacular on the museum floor, hmmm, my reading friend? Do not answer that question.

Yours truly would like to share a thought with you. It looks as if Archer and his spouse were acquaintances of Elliott White Springs, a well-known American fighter pilot with 16 aerial victories to his credit. It so happened that Springs had published, in 1926, a book which proved very, very successful indeed. War Birds: The Diary of an Unknown Aviator was a novel based on letters he had written during the conflict and on the diary of John McGavock Grider, a close friend and comrade who had died in combat in June 1918. The link with Grider was acknowledged in the second edition of the book, a work of fiction based on a real aviator, which led to a 1927 civil suit instigated by Grider’s sister. She won her case, incidentally.

Now I ask you, my Holmesian reading friend, is it possible that War Birds: The Diary of an Unknown Aviator gave Archer the idea of a writing a book, a non fiction work based on a non real aviator? Just askin’.

In any event, the con / scam perpetrated by Archer and his spouse allowed the couple to live quite comfortably during the darkest years of the Great Depression, but back to our story.

As the 1930s bled into the 1940s, interest in the Cockburn-Lange collection gradually waned. How Archer and his spouse got by is unknown. This being said (typed?), the couple presumably had a lot of dough to eat through. Sorry. In any event, Archer worked for the famous monthly magazine Scientific American, as an associate editor, for a brief period of time, in 1945.

The Archers moved to Cuba in early 1952. It may have been around that time that “Wes” Archer asked a friend, the aforementioned Charlton, to hang on to his First World War material. In any event, Archer had a mild stroke in Cuba, in 1952. He passed away there in June 1955, at age 63 or so. His spouse moved to Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States, in early 1959. She passed away there, in July.

An article published the January 1985 issue of the American monthly magazine Smithsonian let the cat out of the bag and provided utterly shocked readers with the juicy details of the con perpetrated by the Archers.

Archer and his spouse would probably be tickled pink to learn that originals of their faked photographs have become collector’s items.

As a sad postscript to that saga, it is worth noting that the aforementioned Schneide, by then an assistant curator at National Air and Space Museum in charge of First World War collections who had worked on exhibitions and aircraft restorations, was escorted out of his place of work in March 1995 and barred from entering staff only areas. He pleaded guilty to charges of theft of government property in July of that year. Said property included pieces of fabric which had once covered First World War airplanes, a First World War aviator helmet, as well as a Second World War flight jacket and some photographs. Schneide had sold that material, purloined between November 1990 and May 1994, and pocketed the money.

While the authorities were lucky enough to find 75 or so Second World War era medals in Schneide’s home, they were forced to acknowledge that he might already have sold a few hundred items of various types.

The disgraced museum employee, a rising star within the First World War aviation history community until his arrest, claimed he had taken the artifacts out of a belief that they were not being properly cared for. The mind boggles.

Schneide was sentenced to 6 months in prison and had to pay $ 20 000 in restitution, a sum which was slightly inferior to the value of the items he was known to have purloined. Was he sacked, you ask? To quote captain Hikari Kato Sulu of the starship Excelsior, are you kidding?

Schneide’s downfall was the result of an incident which had taken place in 1994. One day, a collector of military memorabilia, the chairperson of the department of history at Albion College, in Albion, Michigan, and American history professor at that institution, was offered a pair of rare First World War airplane insignias. John Hall quickly contacted an expert, Alan D. Toelle, to determine their value and authenticity. The latter recalled seeing pieces all but identical to those Hall was describing while doing research at the Smithsonian Institution several years earlier.

Deeply troubled by that piece of news, Hall asked Toelle the name of an expert who could authenticate the insignias. The name he got was that of Schneide, who duly confirmed that authenticity. Now even more troubled, Hall contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Eager to get to the bottom of this, the FBI convinced Hall to meet Schneide while wearing a concealed microphone. The meeting between the nervous academic and the suspected thief took place in March 1994 but did not provide any proof of wrongdoing. The FBI, however, kept at it. As you know by now, it eventually got its man.

And that is it for today, my shocked reading friend. Do not stray from the green pastures of righteousness. Not unless a poopload of moolah is involved and a sure escape route is available. Sorry, sorry. But I still want my cut. I am after all as greedy as Daffy Duck.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)