We are Bi Bi Ba Ba Boum Boum: The saga of the Lunours

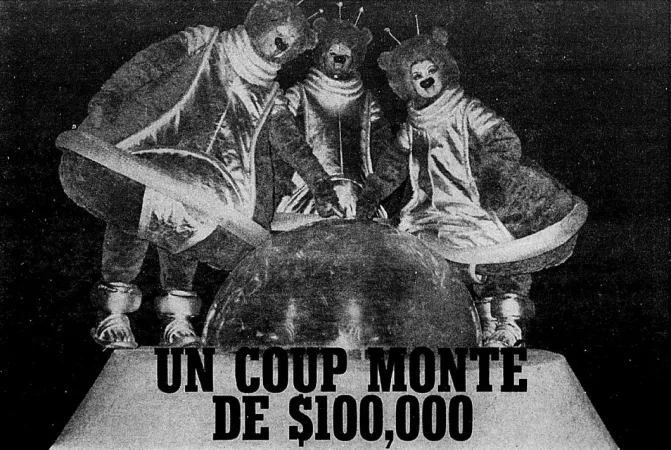

Did you know, my reading friend who likes to keep abreast of what is going on this planet of mad / insane people called Earth, that a flying saucer landed, at sunrise, near the monastery of the Collège Mont-Saint-Gabriel, in Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville, Québec, on 22 February 1970? Yes, yes, a real flying saucer. With 3 crew members.

This landing caused quite a stir among the population of the place. Lady Rumour had a field day. More than one person wondered in fact if nasty sea, sorry, alien creatures (Hello, EG!) were about to launch an invasion of our oh, so peaceful planet. An issue of a regional newspaper published the day after this historic event recounted what had happened. It added, however, that the Canadian Armed Forces were unable to confirm or deny the landing of said flying saucer.

Conscious of the fact that the reaction of the public offered him a golden opportunity to publicise his company and the project which had brought him to Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville, the president of Corporation Image M & M Limitée of Montréal, Québec, René Malo, apologised to its population as well as to that of the surrounding regions and Montréal. The shooting of a pilot television program showing the landing of a flying saucer which aimed to be as realistic as possible (fireworks and ultrasound galore) turned out to be a wee bit too realistic. Malo specified that the 3 extraterrestrials present on the landing site, Bi-Bi, Ba-Ba and Boum-Boum, in other words the Lunours, were completely harmless. Their only goal was to entertain children.

Dare I suggest that Malo and his team actually wanted to create as big a stir as possible to publicise the project which had brought them to Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville? Nah. Who could have thought of such a thing? Who? Who? Malo and his team of course. Their goal was to create as big a stir as possible.

The name of said Malo does not ring a bell, does it? Sigh. He was / is nonetheless one of the most important Québec producers of shows and films of his generation. During the 1960s, Malo welcomed French-speaking international stars such as Charles Aznavour. This world renowned French author composer interpreter, actor and writer of Armenian origin was mentioned in a January 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Malo was also responsible for the Pavillon de la Jeunesse at the Exposition universelle et internationale de Montréal held in 1967. He produced many shows there, each more popular than the last. As you well know, my reading friend, Expo 67 was mentioned in several issues of our you know what since March 2018.

Malo, finally, was the co-producer and distributor of one of the most famous Québec films of all time, The Decline of the American Empire, released, in French, in theatres in June 1986, but I digress.

Interestingly, at least for me, Malo’s press release appeared in the Montréal press on 23 February, a day widely revered by Canada’s wing nuts.

The first controlled and sustained flight of a powered airplane in Canada took place on 23 February 1909. It was carried out by a young Canadian engineer, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, aboard an airplane he had designed. The Aerodrome No. 4 Silver Dart was the most successful machine developed by the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), a group founded in Canada in 1907 by Scottish American inventor Alexander Graham Bell. And yes, my reading friend, you are quite right to think that Bell, McCurdy and the AEA are known to us. It and they were mentioned in previous issues of our you know what:

- Bell, in several issues since October 2018, and

- McCurdy, in several issues since September 2017.

The AEA, on the other hand, was mentioned a few times since October 2018, but I digress.

Speaking of stir / fear, or have you already forgotten Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville and its flying saucer, you will remember that the premiere of Opération-Mystère, a television program produced by the Canadian state radio and television broadcaster, the Société Radio-Canada, in late June 1957, possibly / apparently gave rise to a mini panic similar to the one surrounding the broadcast, at the end of October 1938, of one of the most amazing and scariest Halloween shows ever, by a brilliant young American, George Orson Welles, with the help of his team Mercury Theater, namely a modernised version of the masterful scientific romance dating from 1898 of British author Herbert George Wells, arguably his most famous work, The War of the Worlds. Would you believe that a Photo-Journal reporter actually made a connection between Welles’ hoax / stunt and that of Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville?

Don’t tell me you have forgotten that Opération-Mystère was mentioned in a December 2019 issue of our you know what? Sigh.

By the way, the Société Radio-Canada was mentioned many times in issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since September 2018. As we both know, Welles’ hoax was mentioned in July and December 2019 issues of this same publication known worldwide. Wells and The War of the Worlds, for his and its parts, were mentioned in several other issues, and this since November 2018.

But back to our story or, more exactly, our Lunours.

The Montréal weekly Photo-Journal published an exclusive interview with the sympathetic and totally peaceful extraterrestrials that were Bi-Bi and Ba-Ba and Boum-Boum. It turned out that their landing on Québec soil was very accidental. Their flying saucer having gone haywire, she and they had no choice but to land on Earth.

The Photo-Journal reporter also learned that the Lunours originated from the planet Mena-Menoum, orbiting Mizar / Mirza / Zeta Ursae Majoris, a very real star, quadruple and not double as we thought in 1970, located in the tail of a well-known constellation, the Big Dipper / Ursa Major. Mena-Menoum’s orbit having changed for an unknown reason, this small planet passed between Mizar and a star which was very, very close. The intense heat then burned the surface of Mena-Menoum. The vast majority of Lunours perished.

Yours truly would like to open a parenthesis in this stage of our story. That’s rather dark as a premise for 3 characters whose sole objective was to amuse the children, don’t you think, my reading friend?

What is a quadruple star, you say? A quadruple star consists of a quartet of stars that travel together in outer space. Mizar or, more precisely Mizar A, is the main member of such a quartet. Mizar B, the second member of the team, is approximately 380 light years (3 600 000 000 000 000 kilometres / 2 250 000 000 000 000 miles) from Mizar A. Mizar C and Mizar D are apparently further away, which amounts to saying that the premise of the history of the Lunours did not hold water. Such a distance (24 000 000 times the average distance between the Earth and the Sun) made it impossible to ignite a planet, and ... What do you say, my reading friend with an acute sense of observation? A distance of 380 light years does not correspond to your definition of very, very close? It does not match mine either.

The star which is very, very close to Mizar A is actually called Alcor / 80 Ursae Majoris. The distance between these 2 stars might only be 0.5 to 1.5 light years (4 750 000 000 000 to 14 200 000 000 000 kilometers / 2 950 000 000 000 to 8 800 000 000 000 miles), which amounts to saying the premise of the history of the Lunours did not hold water here either. A distance of 0.5 to 1.5 light year (31 500 to 94 500 times the average distance between the Earth and the Sun) is very little given the size of our galaxy, the Milky Way, but it is still a bit long if you plan to make the journey with a mouse, a dog or a Sputnik.

Yes, yes! You remember having seen (read?) this expression! That’s good. You saw (read?) it as part of a September 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but I digress.

An interesting detail before ending this astronomical digression: Alcor is a double star, in other words it is the main member of a duo of stars that travel together in outer space. If, as some believe, Mizar A and Alcor A travel together in outer space, Mizar A would be a sextuple star, but let us pick up right here the thread of the tale of woe of the 3 Lunours.

On vacation with an uncle at the time of the disaster, Bi-Bi and Ba-Ba and Boum-Boum were sent on a mission. She and they aimed to find a planet with flowers, lots of flowers, where the Lunours could found a colony. If you must know, the Lunours fed exclusively on pollen. Even their flying saucers were fueled by pollen, refined pollen of course.

Their flying saucer and, even more, their onboard computer, a musical computer, the omnitronic, having gone haywire, the 3 Lunours did not know when they would leave Earth. In the meantime, Bi-Bi and Ba-Ba and Boum-Boum intended to eat a lot of pollen, play tourists and make friends. She and they were convinced that they could have a lot of fun on Earth, and this even though she and they considered male (and female?) Earthlings / Terrans far too bellicose. These Lunours were smart cookies under their naïve exterior.

You are probably wondering how this quite incredible story began. Who would yours truly be if I did not pontificate a little on this matter? The saga of the Lunours began with an idea that came to a young (around 24 years old), hyperactive and very ambitious Montréal publicist / impresario, Jean Massue. The latter having noted the considerable impact of the moon landing of Apollo 11, in July 1969, a mission mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since May 2019, he wondered if space type children characters, shown perhaps on television on their own show, could benefit from said impact, bringing tons of cash / dough / moolah back to their creator.

Massue may have wished to create a Québec equivalent, a slightly more childish one no doubt, of a fictional American rock group whose television series went on air, in English, between September 1968 and September 1970, and in French, in a dubbed version, between September 1969 and the early 1970s. Said group, mentioned in a January 2020 issue of our you know what, was called the Banana Splits, but back to our story.

Massue quickly realised that he needed a producer to make his concept a reality. François Chamberland, a friend who worked in the management of programs at the aforementioned Société Radio-Canada, advised him to contact the equally aforementioned Malo. The latter, who was hardly older than Massue (28 years old in March 1970), considered the concept interesting.

To launch said concept, however, the 2 conspirators needed a flying saucer, an item which, as you know as well as I, was rarely offered in the classified ads of daily newspapers of the time. What to do, what to do? By the way, did I mention that our 2 conspirators did not have a penny in their pocket to launch their project?

Coincidentally enough, it turned out that an American firm, Futuro Corporation, was then manufacturing small futuristic prefabricated and movable circular-shaped houses which could very well do the trick. Given the somewhat limited number of potential customers for these Futuros, said firm only produced its houses on order. Massue learned these details after a telephone conversation with an unidentified person, the designer of the Futuro, the Finnish architect Matti Suuronen, perhaps.

A typical Futuro house on display at the Espoon Modernin Taiteen Museo, Espoo, Finland, August 2013. Wikipedia.

If I may be permitted a brief digression, and no, nobody runs to the nearest exit, that’s very rude. If I may be permitted a brief digression, say I, Suuronen designed the Futuro in 1968. It was then a ski chalet. Manufactured under license in Australia, Belgium and the United States as a house made from plastic materials, the Futuro saw its production rights acquired by enthusiasts from around 50 countries. In fact, more than 20 000 people around the world requested information on the Futuro. Would you believe that a male buyer with deep pockets could have his house delivered by helicopter? I assume that this type of delivery was done only in rural areas, but you never know, and I say (type?) male buyer because I doubt that a lady would throw money out the window in so ostentatious a manner.

While it was undeniable that the Futuro aroused plenty of passions, these were in most cases as negative as could be. Imagine such a building in an urban or rural environment, and you will understand the hostility of many neighbours and municipal authorities. Even some banks were reluctant to lend money to potential buyers.

The oil crisis of 1973-74 dealt a fatal blow to the Futuro by causing a dramatic increase in the cost of the plastic materials used for its manufacture. Production ended in the mid-1970s in all the countries involved in this project. There were then very few Futuros (100? 60?) around the world. Very few (60? 30?) still existed as of 2020, including apparently at least one in Québec / Canada, at Mont Blanc, a ski resort in the Laurentians.

If yours truly may be permitted a brief digression, again, I wonder if the Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, should consider the possibility of thinking of acquiring a Futuro. Just sayin’, but back to our story.

Massue conceived the idea of offering Futuro, the firm of course, to promote its futuristic house in exchange for the loan of one of them. He presented this idea to the boss of Mondo-Vision Incorporée, an increasingly well-known production company in Montréal. Better yet, he offered all the cinematographic rights of the Lunours to Roger Cardinal if the latter accepted to film a documentary that would be used to launch the Lunours, a documentary that Futuro could use to promote its futuristic houses. A director / producer / screenwriter increasingly well-known from the 1970s onward, Cardinal considered the idea interesting. Indeed, he considered the idea so interesting that he went to the United States the day after his meeting with Massue.

A Futuro representative considered Massue’s idea interesting. He said he was ready to lend a house to Cardinal and his partners if they paid the transportation costs, which amounted to about $ 4 000. Cardinal thanked his interlocutor for his time and offer, and returned to Montréal. Their piggybank containing not even the shadow of a penny, Massue, Malo and Cardinal were forced to look for their flying saucer elsewhere. Did I mention that the Canadian Department of National Revenue would have apparently demanded payment equivalent to 30 % of the value of the flying saucer during its passage through the border?

Our happy conspirators soon learned that an Ontario firm not identified by yours truly was manufacturing futuristic small circular houses that could very well help them out. They contacted it. A representative of said firm considered their idea interesting. He said he was ready to lend a house to our merry conspirators if they paid the transport costs, which amounted to about $ 1 500. Their piggybank still containing not even the shadow of a penny, Massue, Malo and company were forced to look for their flying saucer elsewhere. What to do, what to do?

Our conspirators then decided to supervise the fabrication of a flying saucer, non-functional of course, by a small Montréal firm, Les ateliers Gingras (Enregistrée? Incorporée? Limitée?). While it was true that said saucer, completed in record time, meaning 2 weeks, cost about $ 7 000, Massue, Malo and Cardinal hoped to sell it for a higher sum in order to make a small profit after paying Les ateliers Gingras.

Massue and Malo were quick to convince some expert technicians from Montréal to join what seemed to be a great adventure. The designer of the flying saucer, for example, was an employee of Radio-Québec, today’s Société de télédiffusion du Québec, or Télé-Québec, named Guy Martin. In fact, virtually all of Radio-Québec’s technical staff ended up getting their hands dirty.

More or less as a joke, Martin said that, with several / many thousands of dollars more, he could have made the flying saucer of the Lunours fly.

Massue and Malo began to prepare the launch of the Lunours, with an almost military precision it must be said, from November 1969 onward. Their team ended up comprising around 140 people, including

- 2 colonels from the Reserve of the Canadian Army,

- 6 brothers from the aforementioned Collège Mont-Saint-Gabriel,

- 6 costumers of the Théâtre du Nouveau Monde of Montréal,

- 7 filmmakers from the aforementioned Mondo-Vision,

- 10 civil and criminal lawyers from Montréal,

- 15 employees from the record distribution centre GRT Records Incorporated in Toronto, Ontario, and

- 60 employees of the advertising agency BCP Incorporée in Montréal.

And yes, you are quite right, GRT Records was a subsidiary of the American firm General Recorded Tape Corporation. BCP, on the other hand, was the first French-language advertising agency in North America.

A record company in Paris, France, Disques Barclay, and some of the staff of its subsidiaries in Montréal and New York City, New York, prepared the launch of a single record carrying 2 original psychedelic rock type songs composed by the very gifted Québec composer and musician François Guy, Nous sommes Bi-Bi Ba-Ba Boum-Boum and Terre Terre. A version in Shakespeare’s language of this record, perhaps especially intended for the vast American market, was released no later than April 1970. The Moonbears, the English name of the Lunours, sang We are Bi Bi Ba Ba Boum Boum and Moonbears around the World.

If yours truly may be permitted a comment, I very much doubt that the voices that could / can be heard on these records were / are those of the Lunours. Just sayin’.

You can hear Nous sommes Bi-Bi Ba-Ba Boum-Boum by going to

Disques Barclay having advanced a large sum to our happy conspirators to finalise the preparations surrounding the launch of the Lunours, said conspirators went looking for a place where they could simulate the landing of their flying saucer. Not wishing to face the wrath of national, provincial and / or municipal governments, Massue, Malo and company decided to film the scene on private land. For one reason or other, money maybe, the Collège Mont-Saint-Gabriel agreed to help them.

Three of the team’s 10 lawyers were at the film site on 22 February in case things went wrong (shots fired by frightened resident(s), assault by a police force or the Canadian Armed Forces, all-out invasion by Klingons, etc.). Indeed, this fear of more or less hostile reaction apparently led Massue and Malo to consult an anthropologist, a psychologist and a sociologist. And no, not an ichthyologist. And no, not a monologuist either. Come on, be serious, please, my reading friend. This being said (typed?), speaking of monologuist, the female member of Lunours was the wife of the famous Québec monologuist / humorist Yvon Deschamps for a few years during the 1960s, but I digress.

By the time the Lunours exploded on the Québec scene, Massue, Malo and company had mobilised the pretty sum of $ 100 000 in talents and hard raised money. They hoped to make significant profits. Indeed, even before their flying saucer landed in Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville, an unidentified firm said it was ready to buy the Lunours for the modest sum of $ 25 000. Massue and Malo politely rejected this offer. They were convinced that their concept was worth much more. According to some, the Lunours could bring in the modest sum of $ 150 000 annually, not to mention the sums that could fall from the sky, or space, once the concept was exported.

How to explain such a sum, you say, my reading friend attracted by greed? That’s very simple. The aforementioned Cardinal proposed the production, by Mondo-Vision, of a television series for children to the management of the aforementioned Société Radio-Canada and the latter agreed, in principle, to embark on the adventure. Draft scenarios were being developed even before the beginning of March 1970.

Massue, Malo and company were already dreaming of Lunours toys, Lunours chocolates, Lunours lollipops, etc., etc., etc. Who knows, these friendly extraterrestrials could end up on cereal boxes consumed by legions of young Quebeckers.

Even their flying saucer could give rise to a series production project, as summer chalets for example.

Yours truly is delighted to inform you that Bi-Bi, Ba-Ba and Boum-Boum made at least one visit to Sherbrooke, Québec, my homecity, a little before mid-March 1970.

She and they were also among the numerous guests of an episode of the Donald Lautrec chaud television music program filmed at the Cité des jeunes in Vaudreuil, Québec, around mid-March. Said episode was broadcasted by the Société Radio-Canada, even before the end of the month. And yes the word was “chaud,” not show – a clever pun to highlight the fact that the Donald Lautrec chaud was… hot.

The Lunours had made their first appearance on television a little earlier in March, however, during an episode of the very popular television music program Jeunesse d’aujourd’hui, broadcasted by Télé Métropole Incorporée, a private television network in Montréal mentioned in October 2017, June 2019 and November 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

I will not teach you anything by telling you, my learned reading friend, that the Québec singer Donald Lautrec, born Donald Bourgeois, was the best known performer of the theme song of the aforementioned Exposition universelle et internationale de Montréal, Un jour, un jour, and its English version, Hey Friend, Say Friend (Hello, MMcC!). Lautrec and Un jour, un jour / Hey Friend, Say Friend were mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but I digress.

The identity of the 3 Homo sapiens who played the roles of the Lunours was known virtually from the first day of their saga. They were Mirielle Lachance (Bi-Bi), Benoît Marleau (Ba-Ba) and Claude Michaud (Boum-Boum) – 3 well known members of Québec’s artistic community. Massue convinced them to participate in the initial phase of his project without being paid. That took some doing.

Did you know that Michaud lent his voice to one of the main characters in Les Pierrefeu, the French dubbed version made in Québec, first broadcasted from September 1971 onward, of the iconic American television situation comedy / sitcom The Flintstones, first broadcasted, in English, between September 1960 and April 1966? Indeed, Michaud lent his voice to Arthur Laroche, the Québec counterpart of Barney Rubble. By the way, Marleau and Lachance respectively lent their voices to the dinodog Dino (Dino) and to Boum-Boum Laroche (Bam Bam Rubble) in this same animated series.

Did you also know that Marleau lent his voice to one of the secondary characters of Cosmos 1999, the French dubbed version made in Québec of Space 1999, an unspectacular Italo British / British science fiction television series mentioned in October 2019 and January 2020 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee? But I digress, again and again.

Without a doubt, at the beginning of 1970, the launch of the Lunours was the most important artistic event in Québec. The group’s success seemed assured.

This being said (typed), clouds soon cast a shadow over the plans of Massue, Malo and company. Rumours of the Lunours’ dissolution were in fact heard even before the end of March 1970.

A music columnist working for a regional Québec daily, Le Nouvelliste of Trois-Rivières, said he was saddened by these rumours. He indeed considered excellent the single record of the Lunours. It might have been too much so, said Jean-Marc Beaudoin. “It is in the realm of fantastic music, with percussion, vibrations, echoes. An astral hymn.” The 2 songs of said single, the aforementioned Nous sommes Bi-Bi Ba-Ba Boum-Boum and Terre Terre “are the kind of music that we hear in discotheques with any strobe and hopping light.”

The music columnist of the important Montréal daily La Presse, Jacques Charles Gilliot, did not share Beaudoin’s enthusiasm for the single record of the Lunours: “The record would not be bad if one understood something about the lyrics, but unfortunately the mixing, which is, it is said, made that way, is in our opinion very bad.” It was a shame, said Gilliot, especially since the lyrics to the songs seemed to be important to the group’s success.

Would you believe that Gilliot was one of the directors of the aforementioned Jeunesse d’Aujourd’hui?

Rumours of the dissolution of the Lunours turned out to be unfounded, however. In fact, the triumphant trio arrived at Montréal-Dorval International Airport even before the end of March 1970 to welcome 2 representatives of a major American firm which had come to Montréal to chat with Massue, Malo and company.

What happened, you ask, my reading friend? Let me enlighten you: Michaud was shown the door by Massue. According to him apparently, the Montréal actor was partly responsible for the difficulties encountered by the promoters of the Lunours during their discussions with the Société Radio-Canada. Indeed, high-ranking people believed that Michaud did not work as a character of a television series for children. Difficult relations between Massue and the Montréal actor did not help either. Another Montréal actor, a much less known one, Jean Asselin, therefore began to wear the costume of Boum-Boum.

This change hardly seemed to improve the status of the Lunours. Let us be blunt: the Société Radio-Canada decided before the end of May 1970 not to broadcast the television program proposed by Massue, Malo and company. As a result, the project was faced with serious money problems. Two of the Lunours, the aforementioned Lachance (Bi-Bi) and Marleau (Ba-Ba), denounced the fact that Massue pocketed all of the fees paid by the aforementioned Télé Métropole following the performance of the Lunours during the episode of the program Jeunesse d’aujourd’hui. Worse still, the checks that Massue had given to Lachance and Marleau were not honoured by financial institutions.

The equally aforementioned Michaud was the only member of the initial trio to receive his emoluments. Ironically, he owed his good fortune to the fact that he was kicked out before Massue’s piggybank was as devoid of content as the conscience of a ... Err, it would probably be better not to mention anyone. A defamation lawsuit can occur so suddenly.

Before I forget, the Union des Artistes Incorporée, the Montréal organization which defended / defends the interests of the members of the Québec artistic community, took steps to ensure that Lachance and Marleau receive their due. Yours truly wonders if either of them ultimately receive a single penny.

While Massue stated in 1971 that he hoped to be able to resuscitate the Lunours or, more exactly, the Moonbears, on American soil, the fact was that no one else believed it.

While Malo’s career subsequently flew from success to success, that of Massue seemed to end badly. I indeed fear that he died (accidentally?) in May 1972, at age 26 perhaps, about 6 weeks after the bankruptcy of his last production company, founded by other people in July 1970. That information really shocked me when I came across it.

Take care of yourself.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)