“Forget that times are tough and grim, cheer up and smile with Sunny Jim” – The crunchy saga of Force Food Company’s Force, the 1st commercially successful wheat flake breakfast cereal on Earth, part 2

Greetings, my reading friend, and welcome to this 2nd part of our article on Force breakfast cereal, a product of the American firm Force Food Company, the part in which you will find out if the 1902 advertising ballyhoo mentioned in the 1st part of said article proved successful, a ballyhoo centered upon a character named Sunny Jim.

To the delight of Edward Ellsworth, the boss of another American firm, Edward Ellsworth & Company, which controlled Force Food, Sunny Jim caught the public’s fancy. People became interested in him and, if yours truly got his facts right, his spouse, his two daughters, his son, his mother in-law, etc. Hundreds of unsolicited advertising jingles soon began to pile up in the offices of Force Food. They eventually filled 5 large scrapbooks.

Would you believe that a Sunny Jim sign painted in December 1902 on the side of a New York City, New York, building was 34.3 or so metre (112.5 or so feet) tall? Wah! Even jaded New Yorkers were astonished by the size of that ginormous sign. By comparison, the text which accompanied it was both short and small: “Vigor, Vim, Perfect Trim, ‘FORCE’ Made Him ‘Sunny Jim.’”

Would you believe, again, that Sunny Jim became a national figure? It has been suggested that, on two separate occasions, a noted divine and an eminent chief justice admonished the people facing them by pointing out his sterling qualities.

According to a September 1902 issue of the American weekly Printers’ Ink, the first national trade magazine for advertising in the United States if not the world, and an influential voice in the trade, Sunny Jim was as well known as the rather unpopular American financier / investment banker John Pierpont Morgan or the rather more popular American President and writer / soldier / politician / naturalist / hunter / amateur historian / explorer / conservationist, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, Junior. I kid you not.

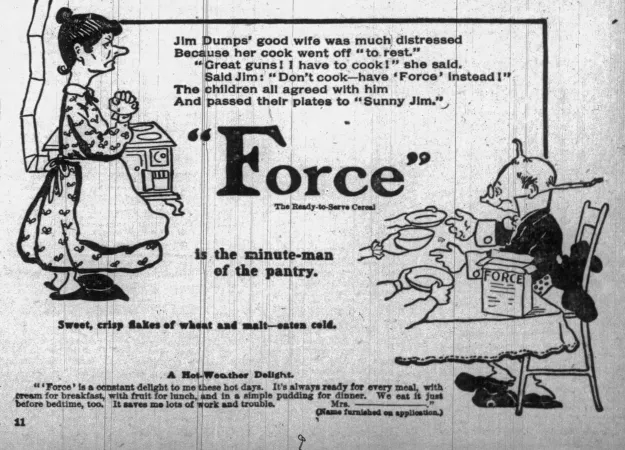

A typical advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York. Anon., “Force Food Company.” Le Journal, 2 October 1902, 2.

Another typical advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York. Anon., “Force Food Company.” La Patrie, 16 June 1903, 7.

Incidentally, Force was available in Québec and Ontario no later than April 1902. A package sold for 14 to 17 cents, sums which corresponded to about $4.45 to $5.40 in 2024 currency.

In June 1902, Force Food looked into the possibility of setting up shop in Brantford, Ontario, or Hamilton, Ontario, in buildings respectively previously occupied by a cotton mill and a foundry. Mind you, Peterboro / Peterborough, Ontario, was also in the running.

That same month, Force Food claimed that the rush of orders was such that it had to use on American soil the new tooling it had just received to equip a factory in Canada. To quote The Brantford Expositor, “It is an open question whether the Force Food people have been making a genuine search for a Canadian location, or are merely shrewd advertisers.” Ow…

In February 1903, Force Food briefly looked into the possibility of setting up shop in St. Catherines, Ontario, but the municipal council could not agree to its demands.

Given that, the firm got in touch with the Hamilton City Council. A deal was soon signed with a Canadian foundry, McClary Manufacturing Company of London, Ontario, regarding the lease of the empty Hamilton factory previously occupied by Copp Brothers Company Limited.

Force Food’s Canadian factory finally opened its doors in May 1903, in Hamilton.

To that effect, advertisements began to appear in newspapers, both in Hamilton and Toronto, Ontario, and perhaps elsewhere, and this no later than June 1903, offering a minimum of $3 a week for new female employees, and up to $7.50 a week once that person became an expert packer and labeller. Those sums corresponded respectively to about $90 and $230 in 2024 currency, which was no great shakes.

It should be noted, however, that weekly earnings of $7.50 were what a typical production worker in the Canadian manufacturing industry took home then. You see, in 1905, the annual salary of that typical worker was $375, a sum which corresponded to about $11 450 in 2024 currency. I kid you not.

This being said (typed?), given that women were always paid less than men, a weekly salary of $ 7.50 was pretty good for a woman in 1903.

In any event, blessed be unions! Where would we, disunited proletarians of the world, be without them? And yes, that is my opinion, but I digress.

Oddly enough, Force Food Company of Hamilton was incorporated only in March 1904. The incorporators were seemingly all American, and this because no Canadian businessman chose, or was allowed, to invest in the new firm.

Did all the hoopla surrounding Force lead a number of American and Canadian grocers to order that product, you ask, my reading friend, and this either willingly or unwillingly? A good question. You might very well be on to something.

This being said (typed?), yours truly must admit that Force Food’s facilities might have been busy places. You see, in early June 1903, the management of the recently opened facility in Hamilton was forced to bring (some of? all of?) its male employees on a Sunday on at least one occasion. Someone contacted the city’s police department, which promptly sent another someone to investigate. As a result, six male employees were charged with a breach of Ontario’s Lord’s Day Act.

The factory’s superintendent stated to the police magistrate that Sunday work was common at Force Food’s factory in Buffalo and that he had no knowledge of Ontario’s act. He asked that the employees be let off with a warning. The police magistrate agreed to dismiss the charges against them but added that there would be trouble if the act was disobeyed a second time. The superintendent assured him that no employee would be working on Sundays from then on.

Yours truly has a feeling that there might have been some slight trouble had the employees been fined. You see, Ontario’s Lord’s Day Act was declared ultra vires in mid-July 1903, by His Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council, in London. Yes, the one in England, but we digress.

Incidentally, the job market in Hamilton was so tight that Force Food could not find all the female workers it needed to keep up with demand, which might explain its unsuccessful attempt to bring in workers on a Sunday.

In that regard, an advertising effort launched in early July 1903 at the latest did not help Force Food’s equally stressed American workers.

Was that effort worth the effort, you ask, my curious and slightly cheeky reading friend? Well, read on and find out.

In mid-1903, Force Food hired a Maine stilt walker known as Professor Elliot, born H.J. Elliot, to play the part of a 3.35 or so metre (11 or so feet) tall Sunny Jim. An otherwise unspectacular gentleman by the name of F.H. Wilson played the part of a 1.65 or so metre (5 feet 6 inches or so) tall Jim Dumps, the surly sod who transformed into Sunny Jim when he had some Force for breakfast.

Those twins, nicknamed Before and After by some, arrived in… Maine in early July with an eager entourage of advertising people and plenty of knickknacks and doohickies for the children of several cities and towns. That team visited several northeastern American states, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, during the summer of 1903 and yes, Maine might have been its first stop.

Towns in at least 2 states, Rhode Island and Iowa, witnessed parades made by men (on stilts??) dressed up as Sunny Jim during the summer of 1903. In that regard, the following advertisement might perhaps be of interest…

A typical advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York. Anon., “Force Food Company.” The Times Dispatch, 4 April 1903, 3.

Sadly, yours truly does not know if the Sunny Jim twins visited Canada at some point. I have a feeling they did not. Indeed, I do not know if they resumed their travels in 1904.

The great commercial success of Force might, I repeat might, have aggravated and / or worried certain individuals, presumably in the United States. You see, in mid-July 1903, Force Food began to place large advertisements in a great many American newspapers, as well as several Canadian ones, published in Québec, Ontario, Nova Scotia and possibly elsewhere. Said advertisement offered a “$5,000. Reward for the Arrest and Conviction of the parties who originated and circulated, the rumor that ‘Force’ Food contained drugs or other injurious ingredients.”

The firm offered another US $5 000 to anyone who could prove that Force ever contained “any drug or other injurious or unhealthy ingredient.”

By the way, those sums corresponded to about $245 000 in 2024 currency, which was certainly no small change.

The cost of all those advertisements was no small change either. A newspaper suggested that this cost might have reached US $50 000, a sum which corresponded to, you guessed it, about $2 450 000 in 2024 currency. The loss in sales might have been comparable. A rumour could be supremely damaging indeed.

And no, no information has come to light regarding whether or not either of the rewards was awarded.

And no again, yours truly cannot believe that those two large rewards were part of some Machiavellian advertising campaign on the part of Force Food. I might, however, be naïve in that regard.

Speaking (typing?) of reward, did you know that Force Food put out a recipe booklet entitled The Gentle Art of Using ‘Force’ no later than April 1904? I kid you not. And no, my facetious reading friend, the diminutive Jedi grand master Yoda had nothing to do with that publication.

A booklet containing numerous jingles, The Story of Sunny Jim, had been published in 1902, I think.

Ready to cut, stuff and sew or else ready to use Jim Dumps and Sunny Jim dolls hit the market no later than 1903. Those 5-colour linen dolls came in at least 2 sizes, one of them 38 or so centimetre (15 or so inches) tall.

As one might have expected, the Jim Dumps dolls proved unpopular and were soon discontinued.

This being said (typed?), both Jim Dumps and Sunny Jim dolls crossed the Atlantic Ocean and arrived in the United Kingdom in time for the 1903 Christmas season.

Would you believe that Force was for sale in Paris, France, London, yes, again, the one in England, and Berlin, German Empire, no later than August, September and November 1902? Or that such sales began in Sydney, Australia, no later than March 1903? Incidentally, Force went on sale in Auckland, New Zealand, no later than October 1903. Better yet, Force Food set up a sales office in Malmö, Sweden, in June 1904. And here are proofs…

An advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York, which proved that this product was for sale in Paris, France, no later than August 1902. Anon., “Force Food Company.” The New York Herald (European edition – Paris), 11 August 1902, 8.

The illustrated section of an advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York, which proved that this product was for sale in London, England, no later than September 1902. Anon., “Force Food Company.” The Daily Telegraph, 19 September 1902, 5.

An advertisement for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York, which proved that this product was for sale in the German Empire no later than November 1902. Anon., “Force Food Company.” Straßburger Post, 17 November 1902, unpaginated.

Did you notice that Force Food did not use our friend Sunny Jim in its 1902 (and 1903?) British, French and German newspaper advertisements? The young person in the English advertisement was known as Miss Prim by the way. That creation of an unidentified English artist was soon cast aside in favour of Sunny Jim.

And yes, my observant reading friend, a fly pushing a box of breakfast cereal was just weird. The last thing a firm like Force Food wanted was to see its product associated with something as unsanitary as flies. Miss Prim indeed needed a less sketchy sidekick! Thank you.

A package of undisclosed size of Force, “the most delicate and delicious of all Cereal Foods, the Great BRAIN and NERVE FOOD,” on the shelf of a store in Sydney, was said to be worth 10 pence around March 1903, a sum which corresponded to about $7.35 in 2024 currency. By comparison, a package (of similar size?) cost 50 pfennigs in the German Empire around November 1902, a sum which corresponded to about $ 5.90 in 2024 currency.

You will of course have noted, my observant reading friend, that the drawings used in the French and German advertisements were identical. Given the animosity between those two countries, I would be curious to know where said drawing originated. Given its overall look, yours truly would bet a few pfennigs that it was German. Anyway, let us move on.

Incidentally, several if not many people in Australia (and England?) had not twigged to the fact that that Force should not be cooked like oatmeal. That little detail had to be pointed out to them in some of the advertisements. Even so, some people seemingly ate their Force soaked in hot milk. Yuk! Sorry.

Did you know that one of the popular advertisements that the young cast of the original stage presentation of Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, in 1904, in London, presented to the creator of that world famous character, James Matthew Barrie, to see if he could identify it, was a popular Sunny Jim advertisement which had that character jump over a fence? The jingle which accompanied said add read as follows: “High o’er the fence leaps ‘SUNNY JIM’ – ‘FORCE’ is the power that lifted him.”

By the fall of 1903, Force was produced in no less than 4 facilities, 2 in Buffalo, 1 in Chicago, Illinois, and 1 in Hamilton. Force Food claimed to produce 360 000 or so packages a day. Wah!

One of the last advertisements for Force breakfast cereal issued by Force Food Company of Buffalo, New York, which included Sunny Jim. Anon., “Force Food Company.” The Prince George’s Enquirer and Southern Maryland Advertiser, 12 February 1904, 1.

All was not well, however. You see, by the spring of 1904, the firm had an entirely new advertising campaign, and the original Sunny Jim had all but disappeared from newspapers all across the United States and Canada – and quite possibly elsewhere. That change in course was caused by a recent change in advertising firm.

The new Sunny Jim drawings and texts were the brainchild of a famous American advertising firm, Calkins & Holden Incorporated, yes, the firm mentioned in the 1st part of this article.

Earnest Elmo Calkins, an American advertising executive who pioneered the use of art and fictional characters in advertising, was one of the loudest promoters of the American advertising industry and its professionalism. Calkins hated Force Food’s original advertising campaign, despite its indisputable success. He set out to change it and…

Just to be clear, yours truly is in no way insinuating that Calkins & Holden deliberately sabotaged Force Food’s advertising campaign. After all, a defamation suit can so easily happen.

Sunny Jim 2.0 as he looked in an advertisement issued by Force Food Company of London, England. Anon., “Force Food Company.” Birmingham Evening Dispatch, 27 May 1904, 6.

Sunny Jim was no longer a simple and whimsical line drawing character, however. Nay. Sunny Jim 2.0 was a weird, if not borderline creepy looking chap with an egg-shaped three-dimensional head. The equally whimsical jingles, on the other hand, were replaced by paragraphs and paragraphs of stolid and often preachy prose which lectured consumers about the merits of good nutrition and positive thinking. Most of those advertisements contained the words “Be Sunny!”

The new advertisements were as captivating as watching paint dry.

A most interesting advertisement issued by a French pharmacist, Edmond Capmartin, to sing the praise of his Poudre Cap. You will of course note the presence of Sunny Jim 2.0. Anon., “Revue de la publicité – Poudre Cap. » La Publicité, July 1905, 22.

The strange appearance of Sunny Jim 2.0 did not prevent a French pharmacist, Edmond Capmartin, from plagiarising him for use in his advertisements for some sort of sodium bicarbonate powder available since at least 1888, the Poudre Cap, which could be mixed with water to produce some sort of (drinkable??) mineral water. Better yet, that same pharmacist also plagiarised the original version of Sunny Jim. The nerve!

Incidentally, Capmartin’s Poudre Cap was quite the elixir, being able to help people afflicted with bladder, kidney, liver and stomach ailments, not to mention albuminuria, diabetes, dyspepsia, gastralgia, gastritis, gout and gravel – or so he claimed.

An equally interesting advertisement issued by the French pharmacist Edmond Capmartin to sing the praise of his Poudre Cap. You will of course note the presence of the original version of Sunny Jim. Anon., “?” Le Progrès, 28 May 1905, unpaginated.

The plagiaristic attitude of Capmartin was duly noted by the dean of French advertising magazines, La Publicité.

Mind you, it might also have been the advertising agency that Capmartin dealt with which committed that crime of lese-Sunny Jim, err, lese-majesty.

But back to Force Food’s new advertising campaign.

And yes, my reading friend, you are absolutely correct. The advertising campaign launched in 1903 by Force Food was one of the most expensive launched up to that time by a food manufacturer. The firm allegedly spent US $500 000 a year on advertisements, a colossal sum which corresponded to about $24 500 000 in 2024 currency. Wah!

The mood of Force Food’s management did not remain sunny for long, however. You see, sales began to falter. Calkins & Holden was shown the door at some point, around 1905 perhaps, perhaps without full payment for the work done or with a hefty bill for a batch of promotional watches it had ordered, or both. Or neither. I simply cannot say.

Dare yours truly suggest that this famous American advertising firm was a textbook example of the ever-increasing professionalising of the advertising profession, a professionalisation which led to a rampant elitism put forward by professional white male Homo sapiens who claimed that the best way to boost sales was to use serious salesmanship, in other words long and serious texts? You are probably right, my cautious reading friend, I shall not dare.

I will, of course, refrain from suggesting that the good people at Calkins & Holden were among the advertising professionals who had criticised the original Sunny Jim and the advertising campaign he had spearheaded. As well, yours truly would never dare to suggest that the more successful the Sunny Jim campaign had become, the more the American advertising community had hated it.

Why such restraint on my part, you ask, my puzzled reading friend, besides the fear of prosecution for defamation? You see, it is my contention that the aforementioned Homo sapiens might have feared that the success of Force’s Sunny Jim advertising campaign, a campaign in which their firms had played no part, might have given ideas to other American manufacturing firms who might have decided to drop the expensive contracts they had signed with said advertising firms and design their own advertising campaigns, which would not have been good at all for the bottom line of the American advertising industry.

Misfortunes rarely coming in packages of one, Force Food suffered a serious setback in February 1904, when one of its Buffalo facilities was seriously damaged, if not all but destroyed in a huge fire which devasted a large swath of the city’s core.

Topping that off, Force Food found itself at the receiving end of a patent infringement suit launched in June 1904 by another American manufacturer of a wheat flake breakfast cereal, Malta Vita Pure Food Company. From the looks of it, that matter was settled out of court.

What might be described as the cherries on top of the fruit cake were the advertising campaigns launched in January and September 1906 by Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company and Postum Cereal Company Limited, a dynamic duo of American firms which would gain fame as the makers of arguably better breakfast cereals known as Corn Flakes and Post Toasties.

The latter product was initially known as Elijah’s Manna, by the way. Oddly enough, that biblical moniker gave serious conniptions to more than a few American religious groups. In turn, Charles William Post had a serious conniption of his own. He stuck to his guns until cuts in sales forced him to turn Elijah’s Manna into Post Toasties, around September 1907.

That, however, was not the full list of bowling balls that Force Food had to juggle with. Nay. You see, Force Food had run into a sticky situation in early 1905. You see, again, its premium scheme was seriously aggravating grocers all across the United States. Said scheme allowed customers to acquire items as varied as air rifles or lorgnettes in exchange from one or more coupons and some moolah.

In April, at a meeting called by the National Association of Retail Grocers of the United States, all but 3 of the country’s producers of breakfast cereals agreed to discontinue their respective schemes. Those dissidents indicated they would discontinue their respective schemes if their competitors did so as well. Failing to reach an agreement, they did not. Sadly enough, those 3 firms accounted for about 80% of the breakfast cereals sold in the United States.

And yes, you are correct, my reading friend, Edward Ellsworth & Company, which owned Force Food and its sister firm H-O Company, was one of those delinquent producers.

In January 1906, at their annual convention, the members of the National Association of Retail Grocers of the United States enthusiastically passed a strongly worded resolution condemning Force Food and H-O.

Within days, the president of that association, John A. Green, sent a letter to all members stating that Force Food and H-O would modify their premium scheme so that it would be no more objectionable than that of other firms.

Many members of the National Association of Retail Grocers of the United States were quite unhappy, h*ll, they were furious, and demanded that Green explain himself, and make public his correspondence with Force Food and H-O. Whether or not the required explanation was provided was unclear.

Mind you, many members of the National Retail Furniture Dealers’ Association were just as unhappy as their counterparts of National Association of Retail Grocers of the United States. You see, the premiums distributed by the delinquent producers of breakfast cereals included cheap pieces of furniture. Yes, furniture. I kid you not.

As time went by, Green came to realise that he had been hoodwinked by the major producers of breakfast cereals. Those firms had no intention of discontinuing their premium schemes. They knew that, as annoyed as many retail grocers were, not all of them wanted the premium schemes to end. All they had to do was to sit tight and wait for the storm to pass, which was seemingly what happened, if only temporarily.

Incidentally, Force’s catalogue of premiums was also available in the United Kingdom and, quite possibly, elsewhere (Canada?).

And yes, the individuals at the head of Force Food and H-O were certainly sharp operators.

One only needs to think of the shenanigans which surrounded the creation of Pawnee Cereal Company in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in early January 1906. You see, those sharp operators had also considered the possibility of setting up shop in Davenport, Iowa. They seemingly dropped that possibility when the local authorities showed some reluctance at their demand that residents of Davenport provide 10% of the new firm’s capital, a sum which amounted to US $ 200 000, or about $ 9 400 000 in 2024 currency.

The good people of Cedar Rapids did not make that mistake. Besides, they only had to raise US $ 100 000, a sum which corresponded to about $ 4 900 000 in 2024 currency. What a deal!

Many people in Davenport were not happy. Their leaders had not shown the required leadership.

Interestingly enough, Pawnee Cereal went into receivership no later than July 1907, only a few months after its factory went into operation, in November 1906.

Oddly enough, though, at least 2 Iowa newspapers published advertisements in November 1907 in which Pawnee Cereal stated that it direly needed 50 women to wrap cereal packages. I know, I know, I do not understand that need either.

In any event, one had to wonder if the good people of Davenport who had criticised the lack of leadership of their leaders thanked them for showing caution when faced with some smooth-talking sharks, sorry, sorry, smooth-talking businessmen wearing chic suits.

Capitalism is a wonderful thing, is it not? To paraphrase the Canadian American public official / intellectual / economist / diplomat John Kenneth “Ken” Galbraith, under communism, man exploits man. Under capitalism, it’s just the opposite. Sorry, sorry. Again.

In any event, the financially troubled group of firms controlled by the aforementioned Ellsworth, namely Edward Ellsworth & Company, Force Food, H-O and Pawnee Cereal, became part of Edward Ellsworth Company in September 1907. Edward Ellsworth, yes, the firm, itself financially troubled, was reorganised in July 1909 and became H-O Company. In turn, that firm became H-O Cereal Company Incorporated in December 1920.

Ellsworth had not been in charge of any of those firms since 1907, when he proved unable to repay the large sum of money he had borrowed to keep his empire afloat. Simply put, Ellsworth had tried to do too much and had overextended himself. He might, I repeat might, have taken his own life not too long after the collapse of his empire.

A rather interesting explanation of the collapse of Ellsworth’s empire could be found in a contemporary publication, but you will have to wait a little while before you can read it. If yours truly may be permitted to quote from a 1987 (!? – 1987 being the year during which I began to work at what is now the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario) romantic comedy and cult film, The Princess Bride, get used to disappointment.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)