“Is This Prophetic of Future?”: University of Saskatchewan professor Robert Dawson MacLaurin and the billowing saga of straw gas, part 2

You came back, my reading friend! I just knew that the billowing saga of straw gas would be a topic you could not stay away from. Shall we begin?

You will remember that we closed the first part of this article of our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thingee in May 1917, in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

As he prepared to board a train which would take him to Eastern Canada and the Eastern United States for a month long trip to gather information on straw compression methods and chamber-oven production, among other things, University of Saskatchewan professor Robert Dawson MacLaurin provided plenty of information on straw gas to journalists.

And yes, that institution of higher learning was, and still is, located in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

A somewhat polished version of MacLaurin’s shpiel, a version published somewhat later, follows.

According to him, 20.3 or so million metric tonnes (20 or so million imperial tons / 22.4 or so million American tons) of straw went unused each year in Western Canada, unless they were burned of course. That much straw, stated he, could be used to produce 4 or so billion cubic metres (140 or so billion cubic feet) of usable gas.

Those latter numbers were / are so hugely, mind-bogglingly big that an analogy might be of use to better comprehend their magnitude. Just imagine, if you can, an 8 or so metre (26 or so feet) thick cloud of straw gas covering every square metre (square foot) of our big blue marble.

The energy released by the combustion of that much gas would be equivalent to the detonation of 32 or so million metric tonnes (31.5 or so million imperial tons / 35.3 or so million American tons) of trinitrotoluene, TNT in abbreviation. An abbreviation which happened to be the title of a song released in 1975 (!) by the Australian hard rock band AC/DC.

Personally, I prefer the 1990 song Thunderstruck by that same band. (Hello, EP and EG!) But I digress.

Our 4 or so billion cubic metres (140 or so billion cubic feet) of gas could, again according to MacLaurin, have produced 1 870 or so megawatts (2 510 000 or so imperial horsepower / 2 550 000 or so metric horsepower), or 7 or so times the energy produced by the quartet of hydroelectric power plants located on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, Ontario, at the time.

That much gas could, again according to MacLaurin, have produced as much energy as 1 400 000 or so metric tonnes (1 385 000 or so imperial tons / 1 550 000 American tons) of gasoline, a volume which corresponds to more than one tenth of the world’s annual production of gasoline in 1917. Buying that much go-go juice at the pump might have cost between 115 or 120 or so million dollars, or 1.825 to 1.9 or so billion dollars in 2023 currency.

Even the lampblack which could be extracted for what was left after the treatment of the straw could be worth 300 or so million dollars, or 4.75 or so billion dollars in 2023 currency. Wah!

And yes, there was also tar worth a pretty penny.

All the talk in Western Canada gradually percolated to the seat of power in faraway Ottawa, Ontario. The Minister of Trade and Commerce, Sir George Eulas Foster, was sufficiently intrigued to request information no later than September 1917.

By then, some domestic straw gas production devices were said to be under test in Saskatchewan. Several others were allegedly being assembled in Winnipeg, Manitoba, so that farmers in that province could test them during the winter of 1917-18.

Sadly, MacLaurin’s hope that the Bureau of Chemistry of the United States Department of Agriculture would be able to launch its own research efforts were dashed when he learned that the appropriation had not gone through the United States Congress. That of course meant that his plans to spend a year in Washington, District of Columbia, to help the staff of the Arlington Experimental Farm, near Alexandria, Virginia, a stay funded in part by the University of Saskatchewan, had to be put aside.

By then, yes, by the winter of 1917-18, the situation had evolved somewhat. You see, fuel shortages had occurred in Canada during the winter of 1916-17, as a result of manpower shortages in coal mines and a soaring demand from industries involved in war production. In June 1917, the federal government had created the post of Fuel Controller to, well, control the supplying, distributing and pricing of all fuels on Canadian soil. The individual who got the nod was the chairperson of the Canadian section of the International Waterways Commission, the surveyor and former Member of Parliament Charles Alexander Magrath, but back to MacLaurin.

In the late summer of 1917, our University of Saskatchewan professor contacted someone in the United Kingdom in order to obtain two of the flexible and collapsible gas bags, possibly made with some sort of rubberised fabric, which were used over there to contain the coal gas used to power a significant number of private and commercial vehicles, and…

You do not believe me, now do you? Sigh… Scepticism when confronted with outlandish claims is a good thing, my reading friend, but it can be taken too far. In any event, the following might convince you.

One of the many English omnibuses whose engines had been modified so they could use coal gas as a fuel, England. Kenneth M. Payne, “New Coal Gas Fuel For Autos Saves Petrol For Air Raids.” The Tacoma Times, 23 January 1918, no page number.

And if you still have doubts, that video should dissipate them once and for all.

But back to our story, and you have a question…

Why was coal gas used, you ask, my reading friend? A good question.

You see, the need for gasoline in the United Kingdom had grown to such an extent as a result of the fighting that some sort of rationing scheme had to be instituted by a Petrol Control Committee set up in late April 1916. In addition, a special tax imposed in June had all but doubled the price of the limited quantities of gasoline available.

Would you believe that some people tried to feed their jalopies with gin or whisk(e)y? I kid you not.

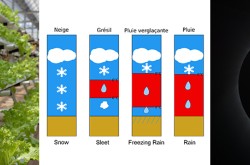

And yes, going under a low bridge with a high vehicle sporting one of those gas bags might have been a… ripping experience. Sorry, sorry. Exceeding a speed of 50 or kilometres/hour (30 or so miles/hour) was also deemed to be a bad idea, but I digress.

Incidentally, a fairly typical automobile fitted with an equally typical gas bag could run for 24 to 32 or so kilometres (15 to 20 or so miles) before running out of… gas. Sorry, but back to MacLaurin’s shpiel.

According to MacLaurin, even though straw gas was not as good a fuel as coal gas, it would be a lot cheaper.

He also seemed to think that, while flexible and collapsible gas bags worked well enough, steel cylinders in which the straw gas could be injected under pressure might be a good idea for use on farm tractors.

Indeed, MacLaurin might, I repeat might, have looked into the possibility of designing a straw gas production device small enough to be mounted on a tractor. Said device would have been fueled with small and seriously compressed bales of hay. Such an arrangement would have seriously increased the autonomy of a tractor and autonomy was indeed an issue.

You see, the aforementioned typical automobile carrying a flexible and collapsible gas bag filled with straw gas might have been able to cover a distance of 19 to 26 or so kilometres (12 to 16 or so miles). That kind of autonomy might have been acceptable for a resident of Montréal, Québec, or Toronto, Ontario. Yours truly doubts it would have been acceptable to a Saskatchewan farmer going to town for some reason or other.

In any event, even a Montrealer or Torontonian might not have been all that interested. Transporting the huge amounts of straw needed to produce the straw gas would not have been cheap. Besides, was the transport of ginormous volumes of straw from the countryside to a bustling city a high priority in wartime?

As was to be expected, information about the work done on straw gas in Canada began to trickle into American newspapers. As far as yours truly can tell, said trickling began in September 1917. By 1918, it had not quite become a flood but the truth was that the number of articles had gone up, from more than 20 in 1917 to more than 120 in 1918.

In that regard, the illustrated article published in the August 1918 issue of the very popular American monthly magazine Popular Mechanics was a tad disappointing. It referred to straw gas as a Canadian invention but did not provide a more precise location, nor the name of any individual involved in the project. One had to wonder if wartime requirements regarding secrecy overcame the need to provide useful information. Just sayin’.

One good thing which came out of that article was that many American newspapers quoted at least part of its content, but rarely included its photograph. Yes, the one used in the first part of this magnificent article.

Did you know that an article on straw gas was published in an October or November 1917 issue of the British weekly magazine The Commercial Motor? Indeed, it was perhaps with the management of that publication that MacLaurin had dealt with in order to obtain the aforementioned flexible and collapsible gas bags.

Oddly enough, articles about straw gas all but disappeared from Canadian newspapers between December 1917 and August 1918. Indeed, the only mentions that yours truly could find during that time slot were two copies of the same humourous and quite long poem, “Just Among Friends,” published in early June in The Saskatoon Daily Star of… Saskatoon by an otherwise unidentified M.H.W.

MacLaurin did not spend those months twiddling his thumbs, however. Nay. He presumably gave classes, for example. Mind you, in February 1918, MacLaurin had also supervised the creation of a natural resources committee within the Saskatoon Board of Trade of… Saskatoon.

And how did the straw gas project reappear in Canadian newspapers, you ask, my reading friend? An appropriate if somewhat obvious question.

Would you believe that said reappearance was linked to the arrival of the aforementioned flexible and collapsible gas bags? Yes, I know. MacLaurin only had to wait 11 or so months for those precious items to make it across the Atlantic Ocean. Mind you, with the United Kingdom and Canada being at war, a butchery war they did not seem to be winning actually, one can understand that the delivery of two gas bags was not a priority.

How many of them were there, you ask, again? From the looks of it, MacLaurin received a pair of gas bags, which was what he had asked for all those months ago. An 8.5 or so cubic metre (300 or so cubic feet) gas bag designed to fit above the passenger compartment of an automobile and a 28.5 or so cubic metre (1 000 or so cubic feet) gas bag which was to be carried in a trailer pulled by a tractor.

And yes, the small khaki gas bag was said to have the following mensurations: length, slightly more than 4 metres (13.5 or so feet), and diameter, 1.8 or so metre (6 or so feet). In other words, that thing was almost as large as the automobile which was to carry it. Even so, the energy provided by the straw gas contained within was equivalent to that provided by no more than 4.5 or so litres (1 or so imperial gallon / 1.2 or so American gallon) of gasoline, which was hardly impressive.

Incidentally, it took 23 or so kilogrammes (50 or so pounds) of straw to produce those 8.5 or so cubic metre (300 or so cubic feet) of straw gas.

As was stated above, while it was true that the autonomy provided by that volume of straw gas might have been acceptable for a city dweller, yours truly doubts it would have been acceptable to a Saskatchewan farmer, unless one or more straw gas production device was installed in every city, town and village in the province.

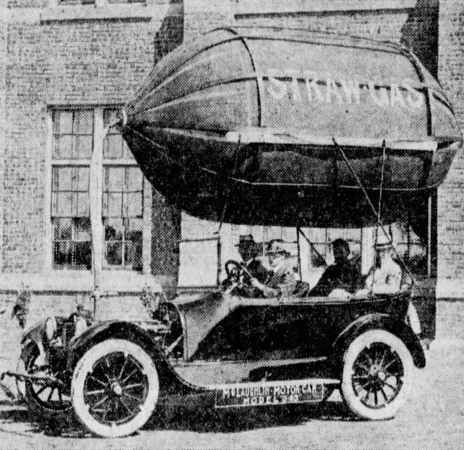

In any event, the vehicle used for MacLaurin’s straw gas experiments was a McLaughlin Model D45 touring automobile, and… Yes, the automobile in the photograph at the beginning of this second part of our amaaazing article, and at the beginning of the first part of that same amaaazing article.

The model D45 got its first dose of straw gas slightly before the middle of August 1918, soon after the installation of its gas bag by a small team led by a professor of Engineering and Farm Mechanics at the University of Saskatchewan, Alexander Roger Greig.

Someone, but apparently not MacLaurin, then took the Model D45 out for a spin down some main streets of Saskatoon. As you may well imagine, the strange looking vehicle did not go unnoticed. Mind you, it might also have covered many kilometres (several miles) outside the city.

Given the rather limited range of the Model D45, the 19 to 26 or so kilometres (12 to 16 or so miles) mentioned above, whoever was at the wheel presumably did not go very far.

As well, starting the automobile proved a tad problematic. Indeed, it soon proved necessary to use gasoline to start its engine. Straw gas was gradually added to the mixture once the vehicle was under way.

Even so, the Model D45 was the first motorised vehicle powered by straw gas in history.

How about the 28.5 or so cubic metre (1 000 or so cubic feet) gas bag mentioned above, you ask, my reading friend? Had it been put to good use? To make a long story short, a rare occurrence in this blog / bulletin / thingee yours truly must admit, no.

The editor of The Saskatoon Daily Star was intrigued enough to publish an editorial on straw gas at the time. A new era in farm life was dawning, he claimed, thanks to MacLaurin’s work.

Even though it recognised that straw gas could revolutionise motoring in Western Canada, Free Press Prairie Farmer, the weekly supplement of an influential daily newspaper, Manitoba Free Press of Winnipeg, Manitoba, also pointed out that it could fill the streets with unsightly gas bags.

You will of course remember that our University of Saskatchewan professor had not invented the straw gas production device at the heart of that project. This being said (typed?), George H. Harrison had seemingly disappeared from the scene. Worse still, at least in certain quarters, MacLaurin was described as the inventor of said device.

In any event, within 2 or so weeks of the first historic outing of the Model D45, MacLaurin was on his way to New York City, New York, where a small straw gas production device was to go on display, in late September 1918, at the 4th National Exposition of Chemical Industries. During his stay in the Big Apple, he would demonstrate the Canadian invention to exposition attendees.

MacLaurin did not go to New York City alone. Nay. With him was Harry Edward Roethe, Junior, of the Bureau of Chemistry of the United States Department of Agriculture. You see, that American department was deeply interested in the straw gas experiments conducted in Saskatchewan.

And no, MacLaurin’s demonstrations and shpiel did not go unnoticed. Representatives of the Commissariat général des affaires de guerre franco-américaines and of the Russian embassy who had left their offices in Washington, District of Columbia, to visit the National Exposition of Chemical Industries, asked for detailed information on the straw gas production device.

Better yet, The Journal of Commerce, one of the most influential and prestigious financial magazines in the United States, published an article about straw gas.

And yes, the staff of the Russian embassy officially represented the provisional government overthrown in 1917 during the Great October Socialist Revolution. Given the bloody civil war which was tearing apart what was technically the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, one could argue that the staff in question represented nothing but a ghost, but back to our story.

Did you know that the United States Department of Agriculture apparently bought the straw gas production device on display in New York City? Well, it apparently did.

Mind you, said department was not the only government entity interested in what was taking place in Saskatchewan. Nay. Again. In late September, Canada’s Honorary Advisory Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, today’s National Research Council of Canada, appropriated $ 1 500, or approximately $ 25 850 in 2023 currency, to cover the cost of the construction of a small straw gas production device in Saskatoon, presumably on the grounds of the University of Saskatchewan.

By the way, the Honorary Advisory Council for Scientific and Industrial Research was mentioned in March 2019, October 2019 and October 2023 issues of our positively stunning blog / bulletin / thingee, but I digress.

With fall at the door and with winter approaching, with fuel prices at an uncomfortably high level too, many residents of Western Canada, including an editorialist of The Winnipeg Evening Tribune of… Winnipeg, Manitoba, were “looking forward, with somewhat eager interest, to a pronouncement from both Provincial and Dominion investigating departments, as to the practical production of straw gas on the farms of Manitoba and the West.”

After all, even though straw gas might not prove to be a practical way to power automobiles, let us not forget that, according to press reports, a domestic straw gas production device might be able to process enough straw in 90 or so minutes to heat a typical farm house for no less than 3 weeks.

Oddly enough, articles about straw gas all but disappeared from Canadian newspapers between January and August 1919. By then, of course, the First World War, was over. Technically. Yes, yes, technically.

You see, the war to end war was still causing wars, both within and between countries, as well as uprisings and revolutions, and this all over Europe, from the Irish Free State to the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, and from Italy to Finland. A fragile peace settled on the continent only in 1923, but enough of that. Back to our story.

In August 1919, MacLaurin delivered an address in Calgary, Alberta, to attendees of the Alberta Industrial Congress held in several cities of that province. And yes, he mentioned that the aforementioned Harrison had originated the idea of using straw gas.

MacLaurin also stated that the Bureau of Chemistry of the United States Department of Agriculture had set up a straw gas production device at the Arlington Experimental Farm of that department, in Alexandria, Virginia, in order to conduct trials, using corn stalks and straw as fuel. That statement was inaccurate, however, as construction of said plant had yet to begin.

By then, yes, my reading friend with the attention span of a flea, by August 1919, MacLaurin’s continuing presence at the University of Saskatchewan was very much in question. One could argue that this very sad aspect of our story had begun in late winter of 1918-19. A handful of faculty members were then making disparaging comments about the administration of the University of Saskatchewan and the institution’s president, Walter Charles Murray, and…

You know what, yours truly thinks it would be best if I delayed the conclusion of our story until next week. What do you think? […] Wunderbar! See ya later.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)