Cowboy traps did not appear yesterday

May I begin this week’s issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee with a heartfelt welcome, my reading friend? Yours truly realises how long this winter has been and how much you look forward to be on the road again, to quote the title of a 1979 song made popular by Willie Hugh Nelson, and the theme song of a very popular Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television series hosted by Wayne Victor Rostad, On the Road Again, which remained on the air between 1987 and 2007.

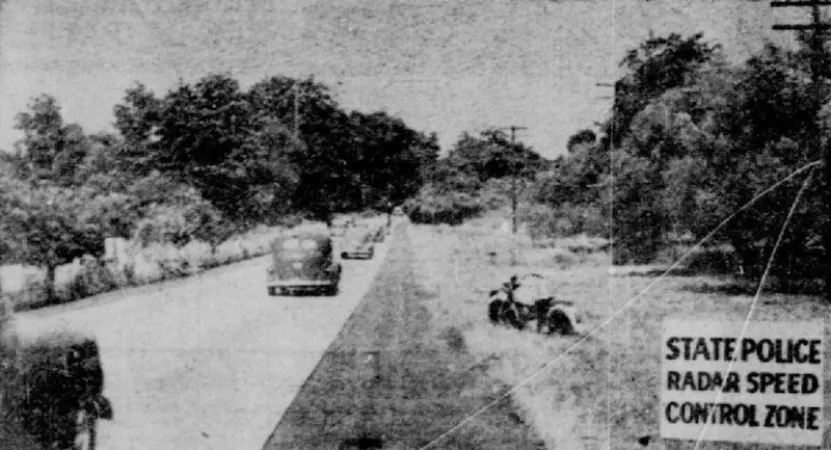

It is therefore with some trepidation that I chose this week’s topic. Yours truly realises how much you do not look forward to the idea of facing the dreaded, dare one say hated, radar guns / radar speed guns / speed guns. Given our common interest in science, technology and innovation, however, I felt compelled to bring to your attention the photo above, and the one below, found in the 16 February 1949, yes, 1949, issue of the La Patrie, a daily newspaper from Montréal, Québec, that no longer exists. I bet you didn’t know that radar guns were that old, now did you?

One could argue that our story began in October 1912, in the United States, with the birth of John L. Barker. In 1933, this gentleman graduated from Johns Hopkins University with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He soon joined the staff of Automatic Signal Corporation, a pioneer in the road traffic signal industry taken over by Eastern Industries Incorporated later in the decade. If truth be told, this company played a crucial role in the transformation of traffic signal controllers, from predetermined fixed-time systems to flexibly-timed pedestrian- and vehicle-activated ones. Barker played an equally crucial role in this transformation. By the early 1960s, traffic control equipment whose design had been influenced in significant ways by his work could be found on every highway in the United States and, quite possibly, Canada.

During the 1970s, Barker was at the forefront of efforts made by the American traffic signal industry to adopt common nomenclature and compatible equipment interfaces. The equipment standards drafted at the same time by the National Electrical Manufacturers Association were subsequently adopted by the Institute of Traffic Engineers / Institute of Transportation Engineers and the Federal Highway Administration.

This being said (typed?), one of Barker’s main claims to fame was the invention of, you guessed it, the radar speed gun. That story began during the Second World War. The landing gear developed by Consolidated Aircraft Corporation with some help from Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation for the legendary Consolidated PBY Catalina maritime patrol flying boat was experiencing problems.

Grumman Aircraft Engineering approached Automatic Signal to see if it could help. Barker and a colleague by the name of Benjamin “Ben” Midlock were put on the case. Realising the need to know the sink rate of the Catalinas as they landed, our dynamic duo cobbled together a primitive radar set. They allegedly turned coffee cans soldered shut into microwave resonators. Said radar set was mounted at the end of Grumman Aircraft Engineering’s runway, facing straight up. Yours truly was not able to determine the usefulness of this piece of equipment. This being said (typed?), the amphibian version of the Catalina turned out to be both successful and versatile.

The time has now come to briefly interrupt this broadcast for a word from your friendly neighbourhood pontificator, namely me.

In the fall of 1939, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) began to search for a replacement for its maritime patrol flying boat, the British twin-engine biplane Supermarine Stranraer, in service for a brief period of time but already almost obsolete. It chose in December a reliable, proven and slightly outdated American aircraft, the aforementioned Catalina. Despite this decision, discussions to produce this twin-engine monoplane in Canada began only after the attack launched by National Socialist Germany against Belgium, the Netherlands and France, in May 1940. They ended around September with an agreement to produce the amphibious version of the Catalina, renamed Canso by the RCAF, by 2 Canadian aircraft manufacturers, Boeing Aircraft of Canada Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, and Canadian Vickers Limited of Montréal.

As a first step, Boeing Aircraft of Canada assembled 55 Canso with parts manufactured by Consolidated Aircraft. Given that this material was not always available in time and in sufficient quantity, the program was faced with delays. The first Canso flew in July 1942. In 1943, in collaboration with the American and British governments, Canada’s Department of Munitions and Supply deeply modified the production program of the aircraft maker. Boeing Aircraft of Canada produced just over 300 flying boats, financed through the Lend Lease Act, for the United States Navy, the Royal New Zealand Air Force and the Royal Air Force.

Canadian Vickers, on the other hand, was awarded a major Canadian contract in 1941. Its factory in downtown Montréal, somewhat old and congested, was insufficient for the task, however. The Department of Munitions and Supply thus bought a vast piece of land in Cartierville, a suburb of Montréal, and erected a factory that the aircraft manufacturer would manage independently. The transfer of the operations was done once and for all in July 1943, 7 months after the first flight of the first Canso made in Québec, in December 1942. Canadian Vickers having decided to abandon aeronautical production during the summer of 1944, a crown corporation, Canadair Limited, was created in October and took control of the plant in November. Canadian Vickers / Canadair ultimately produced about 370 Canso / Catalina amphibians for the RCAF and the United States Army Air Forces.

The total production run by Boeing Aircraft of Canada and Canadian Vickers / Canadair therefore came to approximately 730 amphibians and seaplanes. The RCAF used the Canso until November 1962. Manufactured in greater numbers than any other flying boat / amphibian in its class, the Catalina and its derivatives were / are among the most successful maritime patrol aircraft of the 20th century.

Yours truly would very much like to pontificate even more about the Catalina, but now is not the time. I share your disappointment, believe me, but such is life. And yes, my reading friend, Canadair was mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2017, but back to our business.

And yes again, the Department of Munitions and Supply was mentioned in a September 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. You may also be pleased to hear (read?) that an example of Canso can be found in the amazing, yes, amazing, collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. Now back to our story.

All right, all right. I’ll grant you a micro pontification on the Catalina. Did you know that 27 or 40 flying boats of this type were manufactured under license in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics around 1939-40? While a few carried military colours and markings during the Second World War, a majority were used as civilian aircraft, carrying passengers and / or cargo.

During the Second World War, Barker seemingly mounted the primitive radar set he had developed near a window of the family home. He tested it on automobiles that drove though a nearby intersection. This writer cannot say if Barker had already realised that such a device could give police forces a precise way to measure the speed of automobiles, thus changing forever the rules of the road. In any event, after the war, he put that same equipment, or an improved version thereof, in the trunk of his automobile and measured the speed of vehicles circulating on a Connecticut parkway.

In 1947, the Connecticut State Police deployed a radar set on a road near Glastonbury, arguably creating the world’s very first speed trap. In the interest of fairplay, warning signs were set up by the side of the road. Better yet, officers only issued warnings during what could be described as a field trial of the new device. Glastonbury was chosen because a high number of accidents occurred there. In February 1949, the Connecticut State Police went back there. The radar set it deployed was used to issue speeding tickets, as well as warnings.

I must admit I had some misgivings at the idea of quoting the very long caption of the photos that form the visual core of this article. It is my hope that you will find it as interesting as I did.

Speed fans of Gladstonbury, Connecticut, had better watch out now or they will be quickly trapped by the “little black box” that we see in the picture below. As early as next week the state police will use radar to discover those who go too fast on the road. However, motorists will receive a proper warning when they enter the radar patrolled area, as can be seen in the top photo. A man parked near the radar on the road, heading for New Haven, will note the speed of passing cars as recorded by the device. The officer will forward the offenders’ license number to another officer stationed farther away and the latter will deliver the tickets.

An Automatic Signal speed radar used near Glastonbury, Connecticut. Anon., “L’actualité en images – Pièges à comboys.” La Patrie, 16 February 1949, 14.

And yes, the name Gladstonbury should be spelled Glastonbury, but back to our story.

The 1947 trials did not go unnoticed. A speed radar was seemingly used in 1948, near Garden City, New York. Whether or not the police force involved issued speeding tickets is unclear. The same could be said of the speed trap set up near Columbus, Ohio, no later than January 1949. Before long, there were speed traps in multiple states.

By late 1952, the Automatic Signal Electro-matic Speed Meter, as Barker’s invention was officially named when put in production, was used in 31 of the 48 states of the United States, and in other countries as well. In Connecticut alone, no less than 3 000 speed nuts had been caught. While more than 2 500 drove way with a warning, a good 450 were arrested and penalised.

If I may be permitted to include some local content in this story, the Sûreté provinciale, in other words the provincial police service of Québec, acquired its first speed radar in the spring of 1953. The Sherbrooke Police Department of Sherbrooke, Québec, yours truly’s hometown, had one no later than October 1953. It may well have been the first municipal police force in the province to be so equipped.

The Electro-matic Speed Meter was not exactly a hand held device. Its 20 or so kilogramme (45 pounds) radar tracker and receiver unit could be mounted on the fender of a police car, or a tripod. It tracked a vehicle for a distance of up to 90 metres (300 feet) and automatically recorded its speed on an indicator mounted inside or outside said police car. The speed recorded was accurate within 2 %.

To quote Barker, “the most important part of the speed detector may have nothing to do with its hardware, drivers change their behaviour when they think there’re being watched.”

As was to be expected, many individuals in many locations tried to contest the validity of their speeding tickets. From the late 1940s until the mid 1950s, if not later, Barker frequently appeared in court to defend his invention. Few individuals were successful in contesting the validity of their speeding tickets.

The radar guns used in 2019 are, of course, incommensurably more sophisticated than the ones used in 1949. You may please to hear (read?), or not, that various police departments are begun using lidar guns / lidar speed guns in the first decade of the 21st century, and… You seem perplexed, my reading friend. You don’t know what a lidar is, now do you? Well, neither do I. To quote Hellboy, the grumpy nacho and cat loving hero of the very popular eponymous 2004 movie, let me go ask.

All right. I have something. While the word radar stands for RADio Detection And Ranging, something I did not know, lidar stands for LIght Detection And Ranging. The light in question was emitted by a laser. And yes, that word is also an acronym. And no, I’m not going online to find out what it means. You can do that yourself.

Barker retired in 1981, after almost half a century spent at Automatic Signal, a company owned by Laboratory for Electronics Corporation since 1956 or so. Sadly, he died in January 1982, at age 69.

Be careful out there, my reading friend, and please obey the rules of the road.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)