“Petrol will never kill electricity, especially if the latter is defended by a Kriéger.” Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger and his electric automobiles, including some of the first hybrid vehicles on planet Earth, part 3

Top of the morning to you, my reading friend, and welcome to this 3rd part of our examination of the career and automobiles of French engineer / businessman Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger.

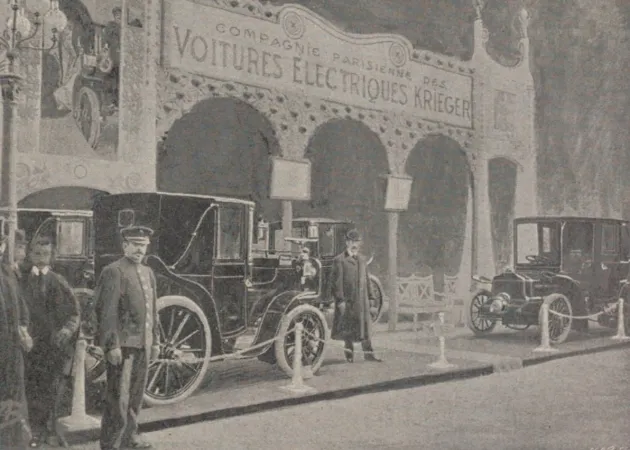

Did the image of the stand of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques at the December 1903 Exposition internationale de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports, in Paris, France, yes, the one you have just seen, please you? Wunderbar! So, here is another one.

The stand of the Compagnie des voitures électriques at the Exposition internationale de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports, Paris, France. Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger was at its entrance. A.B., “La voiture à transmission électrique Kriéger.” Le Monde sportif, 25 December 1903, 9.

Indeed, business seemed to be going better and better for the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. As stated in a December 1903 issue of a short-lived Parisian sports daily, Le Monde sportif, words translated here, “Kriéger is the supplier of the chic, wealthy clientele.” There was therefore nothing surprising in the fact that important Parisian automobile dealers contacted him during said exhibition, and this in order to reserve part of his production.

It should be noted that Kriéger, or one of its collaborators, had the good idea of offering automobile enthusiasts and potential customers the opportunity to try one of the firm’s 5-seater hybrid vehicles, and this throughout the event. Said vehicle approached 75 kilometres/hour (more than 45 miles/hour) on a good, straight road. It obviously did not go that fast in the busy streets, boulevards and avenues of the City of Lights.

A brief digression if I may. That hybrid vehicle consumed 20 or so litres of gasoline per 100 kilometres (14 or so miles/imperial gallon / 12 or so miles/American gallon), a huge figure when compared to the consumption of a current hybrid vehicle.

That same hybrid vehicle, yes, the 1903 one, might, I repeat might, have been the one which brought the Minister of commerce, industry, and posts and telegraphs, Georges Trouillot, to his office after his visit to the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports, a visit which had included a detailed examination of the stand of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. Kriéger had obviously answered his many questions himself.

It went without saying that Trouillot certainly visited other stands during his visit.

And yes, you are very possibly, if not probably right, my eagle-eyed reading friend, the 5-seater hybrid vehicle made available to automobile enthusiasts and potential customers who visited the 1903 Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports was identical to the one found in the photograph at the very beginning of the 1st part of this article.

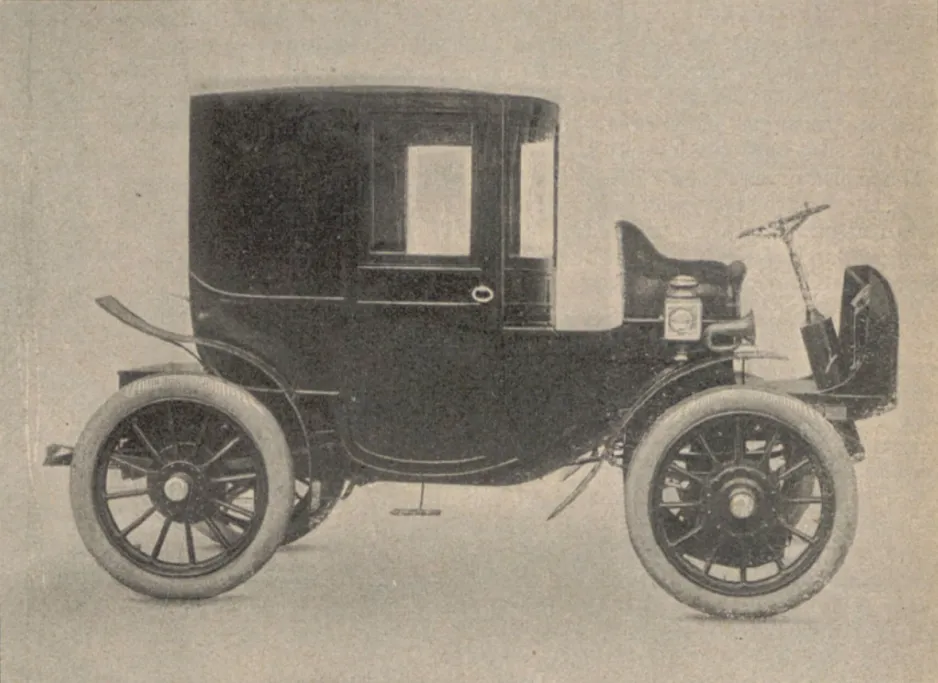

And here are photographs of two types of electric automobiles produced around that time by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques for its chic, wealthy clientele.

A typical electric victoria produced by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques for its chic, wealthy clientele. Maurice Chérié. “Les grandes marques au Salon de l’automobile.” Paris illustré, 2nd issue of December 1904, 20.

A typical electric landaulet produced by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques for its chic, wealthy clientele. Maurice Chérié. “Les grandes marques au Salon de l’automobile.” Paris illustré, 2nd issue of December 1904, 20.

Would you believe that, during the winter of 1903-04, Kriéger had the luxury of crossing the Alps, at the wheel of one of his hybrid vehicles? He subsequently travelled through part of Italy on board. Crossing the Alps in the middle of winter, in an automobile without a heating system, took some doing I would say.

In March 1904, the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques apparently participated for the first time in the Corso Fleuri of the Carnaval de Nice, in… Nice, France. The management was not unaware that this parade of allegorical floats and flowered automobiles attracted large crowds.

The fact that the hybrid vehicles participating in said parade had come from Paris by road, thus covering a distance of 930 or so kilometres (580 or so miles), certainly did not go unnoticed.

And yes, Kriéger himself was among the drivers. Indeed, he took part in the Concours d’élégance which was held at the end of March, in front of the famous Casino de Monte Carlo, in the principality of Monaco. Here again, the hybrid vehicle he drove did not go unnoticed.

It went without saying that hybrid vehicles of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques also participated in the Exposition internationale de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in Nice in April 1904. Indeed, they were, it was said, by far the most noticed by the chic, wealthy clientele of the great Nice hotels. A clientele which was both European and American. American in the sense of American continent, of course. A Toronto, Ontario, woman was / is indeed just as American as a New York, New York, man.

At least one hybrid vehicle also took part in an event taking place in Vienna, Austro-Hungarian Empire, between April and June 1904, I think, the Internationale Ausstellung für Spiritus-Verwertung und Gärungsgewerbe, in other words the international exhibition of the valorisation of spirits and fermentation. And yes, the piston engines of said hybrid vehicles burned alcohol.

The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques did not receive a single medal, however. You see, Kriéger was part of the jury which examined the vehicles which participated in the automobile section of that exhibition.

Indeed, Kriéger was not only interested in alcohol as a fuel for his hybrid vehicles. Nay. He also examined the use of economical fuels such as lean gas, a type of natural gas with a relatively low energy content, both for passenger cars and fiacres and for heavy duty vehicles (trucks and omnibuses), or even light trains.

The example of the hybrid truck of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques equipped with an electric searchlight. J. Caël, “The new Kriéger electric truck.” La Locomotion automobile, 5 January 1905, 86.

One of the trucks in question was equipped with a powerful electric searchlight capable of illuminating a battlefield. The armies of several European countries were said to have been very intrigued by that vehicle involved in major manoeuvres of the Armée de Terre which took place in eastern France during the summer of 1904.

Several lighter hybrid vehicles, each of them dragging a powerful electric searchlight, also participated, it was said, in the major manoeuvres of 1904.

Business was so good for the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques at that point and the number of electric and hybrid vehicles reached such a level in Paris that a garage exclusively intended for them opened its doors around the very beginning of October 1904. Two hundred or so electric or hybrid vehicles could find a spot therein. That was where the former’s rechargeable batteries could be recharged overnight so that they would be ready to transport their illustrious owners.

That garage would have 300 or so spots towards the end of 1906, including 100 or so reserved for rental automobiles. That expansion seemed to be associated with the installation of 2 automobile lifts which left from the ground floor to serve the 2 floors above.

Before I forget, it was in 1906 that the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques signed a contract to build a second factory in the suburbs of Paris. You see, its Parisian factory was no longer able to meet demand.

A brief digression if I may. After all, once is not customary. The head of the firm which delivered the aforementioned automobile lifts, Abel Pifre, had founded, no later than January 1881, the Société centrale d’utilisation de la chaleur solaire – quite possibly the first producer of solar motors, distillers and cookers in the world.

Before I forget, the Société des garages Kriéger et Brasier was created in December 1905, in order to rent, maintain and sell automobiles.

The wing nut that you are, my reading friend, will undoubtedly recognise the name Brasier. During the First World War, the Société des automobiles Brasier produced under license many Hispano-Suiza 8B aircraft engines whose reliability left much to be desired. Pilots of fighter units of the Royal Flying Corps of the British Army equipped with Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5s paid the price for that deficiency, for example.

You did not think that yours truly would find a way to talk about aviation in a text about electric and hybrid vehicles, now did you? Surprise, surprise!

And yes, the wunderbarish collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes an SE 5, but back to the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques and the year 1904.

A questing pause if I may. What was the number of automobiles, and this both electric and hybrid, produced in 1904 by said firm and its 400 employees? No idea? Here are three numbers, choose the right one: 24, 240, 2 400 and 24 000.

I offered you 4 numbers and not 3, you say, my reading friend? So what? Which one do you choose? 2 400? A plausible number, but an inaccurate one. The number to choose was (drum roll) 240. Yes, yes, 240. I kid you not.

By way of comparison, in 1905, the French automobile industry produced between 14 000 and 20 500 vehicles.

By the way, it was in 1905 that this industry lost its first place to the American automobile industry.

In 1905, the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques produced 280 passenger cars and fiacres. Half of that production remained in France, including around 125 vehicles sold in the city of Paris alone.

That tiny number, combined with the great popularity of its vehicles with an elegant, dare I say feminine, clientele, which could no longer tolerate horse-drawn vehicles and their sweet scent of manure, forced the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques to put a stop to its rental department between April and October 1905. It simply did not have enough vehicles on hand to meet demand, but I digress.

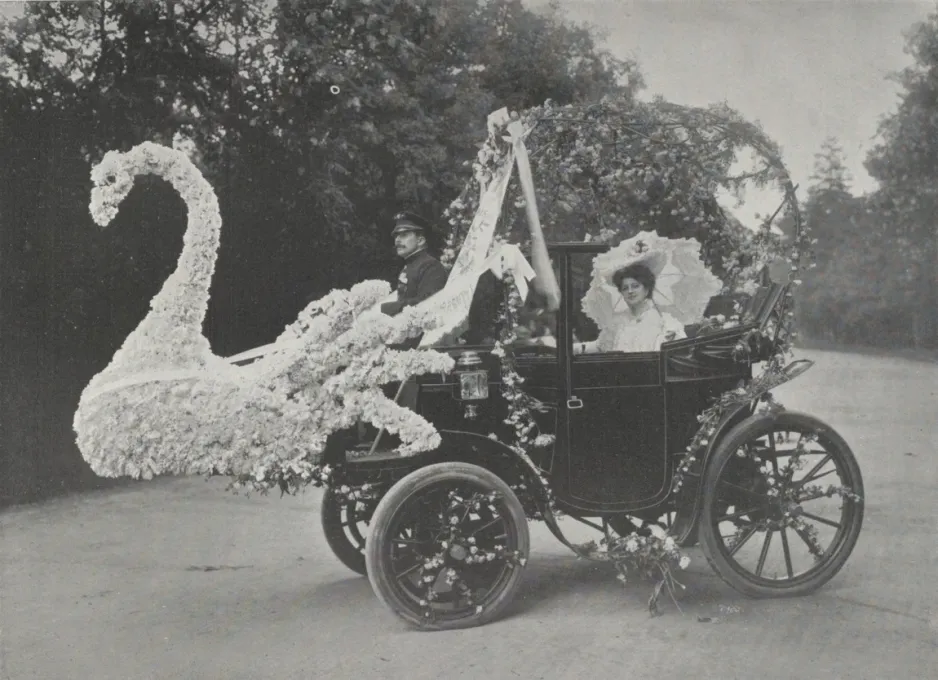

As for the elegant, dare I say feminine clientele, please take a look at the following…

The electric landaulet of the famous French actress / dancer / singer Arlette Dorgère, born Anna Mathilde Irma Jouve, Fête des fleurs, Paris. Anon., “Le silencieux landaulet électrique Kriéger.” Les Sports modernes, May 1905, unpaginated.

Held annually in the Bois de Boulogne, a vast Parisian park much appreciated by people who were light years away from the hoi polloi, the Fête des fleurs aimed to raise funds intended for the Caisse des victimes du devoir, a private organisation which gave those funds to victims of duty, whoever they might have been, or their survivors.

The famous French actress / dancer / singer Arlette Dorgère, born Anna Mathilde Irma Jouve, made it a point to participate in the Fête des fleurs as much as possible. In 1906, for example, the electric victoria manufactured by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques in which she took place literally collapsed under flowers. Indeed, that vehicle won the grand prize of honour.

Yours truly must, however, admit to liking more the electric vehicle in which Dorgère took place during the Fête des fleurs of 1905. Yes, the one in the photograph above. Anyway, let us move on.

By the way, electric automobiles were the only horseless carriages which could parade among horse-drawn vehicles at the Fête des fleurs, and this for obvious reasons (low noise and olfactory levels).

With your permission, or without it if necessary, yours truly would like to mention two other elegant users of an electric automobile from the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques: the famous French actress / courtesan / dancer Émilienne d’Alençon, born Émilienne Marie André, and the equally famous actress Réjane / Gabrielle Réjane, born Gabrielle Charlotte Réju.

A male owner also deserves to be mentioned here because of his contribution to the development of aeronautics at the beginning of the 20th century. The French industrialist / philanthropist Joseph Marie Pierre Lebaudy collaborated with his older brother, the French politician / industrialist Marie Paul Jules Lebaudy, to manufacture between 1902 and 1915 a series of semi-rigid airships used for the most part by the Armée de Terre.

Another brief digression if I may. The popularity of the technology developed by Kriéger was not limited to France alone. Nay. An English firm, Electromobile Company Limited, formerly known as British & Foreign Electrical Vehicle Company Limited, yes, yes, the one mentioned in the 2nd part of this article, acquired the British production rights for said technology at an undetermined date.

And no, yours truly does not know if Electromobile manufactured vehicles which used Kriéger’s technology. Sorry.

In 1906, the German firm Hansa-Automobil Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung acquired the production rights to the technology designed by Kriéger. More than 100 electric fiacres would soon be on the road in Berlin, German Empire, and other cities in that country. Hansa-Automobil also delivered around 75 vehicles to a fiacre firm in Amsterdam, Netherlands, Amsterdamsche Taxameter Automobiel Maatschappij Naamloze Vennootschap, between 1910 and 1912. Also in 1910, the management of the Berlin offices of the Reichpost acquired 25 electric or hybrid postal vans.

It should be noted that, in 1908, a German firm, Norddeutsche Automobil und Motoren Actiengesellschaft (NAMAG) acquired the rights to produce Kriéger’s technology held until then by Allgemeine Betriebs-Gesellschaft für Motorfahrzeuge, a German firm mentioned in the 1st part of this article.

As its name suggested, NAMAG was associated with the major German shipping company Norddeutscher Lloyd Actiengesellschaft. The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques and a consortium of German banks had participated in its creation.

We should also mention that the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques founded a subsidiary in Italy in 1905, the Società Italiana Automobili Kriéger, which became the Società Torinese Automobili Elettrici in 1907, following the end of its association with the French firm.

Two other subsidiaries, I think, Krieger Electric Carriage Company Limited and Krieger Electric Carriage Syndicate Limited, had been established in England no later than 1903 and 1904. Yours truly must confess to not really understand how those firms differed. Indeed, I have the impression that they did not manufacture a single vehicle, confining themselves to selling, operating, storing and / or charging vehicles produced in France. End of digression.

It went without saying that the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques took part in the Concours de véhicules industriels (Transport en commun – Transport de marchandises) et de fourgons militaires organised by the Automobile-Club de France which was held in July and August 1905.

The firm sent a double-decker omnibus and a truck, both of them hybrids, the latter carrying a powerful electric searchlight. Those two vehicles impressed with their reliability in their respective categories, namely public transit vehicles – at least 30 seats, intended for the Compagnie générale des Omnibus de Paris, and goods transport vehicles – payload of more than 2 000 kilogrammes (more of 4 400 pounds).

It should be noted, however, that the position of the engines and the rudimentary waterproofing of the entire propulsion system apparently made the omnibus in question particularly vulnerable in the event of rain, which was not ideal, you will agree.

To answer the question which is gradually condensing in your little noggin, there did not seem to be any ranking with winners, which was a tad curious.

Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger at the wheel of the 4-seater electric coupe with which he travelled from Deauville to Paris without recharging, Deauville, France. Anon., “Le raid Kriéger.” L’Auto, 2 September 1905, 1.

A 4-seater electric coupe identical to the one in which Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger made the Paris-Deauville round trip. Argus, “Le raid Kriéger.” Le Monde Illustré, 9 September 1905, 586.

Mind you, Kriéger was just as successful in late August and early September when he made a round trip in a 4-seater electric coupe between Paris and Deauville, France, a popular seaside resort in Normandy, a total distance travelled of 400 or so kilometres (250 or so miles). He easily beat the time achieved about 2 weeks earlier between Paris and the neighbouring seaside resort of Trouville-sur-Mer, France, by the boss of the Société anonyme des automobiles électriques A. Védrine, a certain… A. Védrine.

Would you believe that Kriéger and the driver of the electric landau who accompanied him throughout the journey had the luxury of putting the pedal the metal once they arrived in Deauville? They both managed to approach 60 kilometres/hour (38 or so miles/hour) over a short distance. Indeed, Kriéger had approached 71 kilometres/hour (44 or so miles/hour) along the way. Wah!

Just like his rival, Kriéger had the luxury of making the return trip without recharging his vehicle’s rechargeable batteries. He thus managed to maintain an average speed of 40 or so kilometres/hour (25 or so miles/hour). That performance, which far exceeded that of Védrine (31 or so kilometres/hour (19 or so miles/hour)), demonstrated that automobile tourism in an electric automobile was no longer a myth.

This being said (typed?), the fact was that the vehicles of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques used during the trip to Deauville were equipped with high performance rechargeable batteries in order to be able to make the journey as quickly as possible. That detail was seemingly not made public, however.

And no, my wingnutty reading friend, the Védrine in question was not related to Charles Toussaint Védrines, better known under the name of Jules Védrines, with an S, said Védrines being mentioned in March 2022 issues of our aerial blog / bulletin / thingee.

The stand of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques at the December 1905 Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports, Paris, France. Anon., “Le 8me Salon de l’automobile.” Le Sport universel illustré, 24 December 1905, 831.

Is it necessary to note that the stand of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques attracted the attention of many people who visited the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in Paris in December 1905, including that of the French President, Émile François Loubet, and the Minister of agriculture, Joseph Ruau? Just as I thought.

And yes, the 4-seater electric coupe aboard which Kriéger had made his round trip between Paris and Deauville occupied pride of place in said stand. A hybrid omnibus also shuttled between the Grand Palais des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs, which housed the exhibition, and the Bourse de Paris.

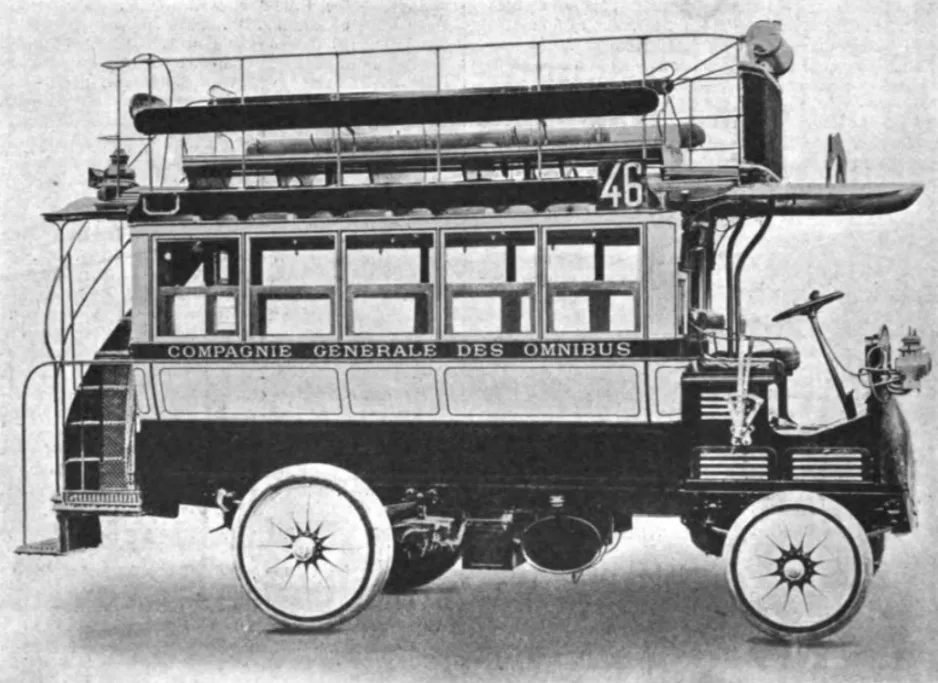

That vehicle was one of the 7 omnibuses supplied by various manufacturers that the powerful Compagnie générale des Omnibus used for comparative tests throughout the duration of the exhibition. And here is the one provided by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques.

The hybrid omnibus that the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques supplied to the Compagnie générale des Omnibus for the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in Paris, France, in December 1905. Anon., “Traction – Omnibus pétroléo-électrique de la Compagnie générale des Omnibus de Paris.” La Revue électrique, February 1906, 82.

Incidentally, the Compagnie générale des Omnibus acquired the Kriéger hybrid omnibus in question in January 1906. Yours truly unfortunately does not know if it ordered others.

Would you believe that the aforementioned hybrid truck equipped with a powerful electric searchlight lit up the surroundings of the Grand Palais des beaux-arts et des arts décoratifs throughout the duration of the exhibition? As a publicity stunt, one could hardly have done better.

Mind you, the fact that the King of Portugal, Carlos I, born Carlos Fernando Luís Maria Vítor Miguel Rafael Gabriel Gonzaga Xavier Francisco de Assis José Simão of house Bragança Sabóia Bourbon e Saxe-Coburgo-Gotha, used a vehicle of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques to get to an exhibition of industrial vehicles and motorboats in Paris did not exactly go unnoticed.

This being said (typed?), Kriéger realised very well that the gasoline automobile was gaining more and more fans. Indeed, those vehicles were, by far, the most numerous in Paris.

Although his electric or hybrid vehicles were those that one most often encountered on the boulevards and avenues of the French capital, Kriéger realised just as well that other French firms manufactured excellent electric vehicles. Let us not forget, it was the Société anonyme des automobiles électriques A. Védrine which had won the 1905 Concours de voitures de ville. The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques actually came in 3rd place in that fiacre competition.

Faced with those states of affairs, Kriéger continued to show imagination. Would you believe that, in February 1906, he filed or obtained, I cannot say, a patent for a hybrid vehicle whose engine, the one which activated a dynamo which powered the 2 electric motors which turned the driving wheels of said vehicle, was a gas turbine. Yes, yes, a gas turbine. I kid you not.

And no, that patent did not give rise to the making of a prototype.

The history of the gas turbine actually went further back in time than one might imagine.

It was in fact around 1791 (!) that John Barber, an English inventor / coal mine manager, filed a patent for a horseless carriage which included the basic elements of a gas turbine. That vehicle was never built and could not have been built, given the technology of the time.

The design of what could be described as the first real gas turbine was found in a patent that the German author / inventor / photographer / stenographer Karl Heinrich Franz Stolze obtained in 1872. Even though a prototype of that engine was finished, it proved unable to operate under its own power. The first gas turbine to achieve that feat was the brainchild of the Norwegian engineer / inventor Jens William Ægidius Elling. That prototype was completed in 1903.

The development of relatively powerful and reliable gas turbines still required some time. The first aircraft powered by a gas turbine, the Heinkel He 178, flew in August 1939, in Germany. The first locomotive powered by a gas turbine, the Schweizerische Lokomotiv- und Maschinenfabrik / Brown, Boveri & Compagnie Am 4/6 1101, made its maiden voyage in September 1941, in Switzerland. The first automobile powered by a gas turbine, the Rover JET1, rode for the first time in March 1950, in England, but I digress.

And it is on this technological digression that the 3rd part of this article ends. See ya later.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)