It could (and should?) have been one of the greats: Canada’s Fleet Model 50 Freighter bushplane

As you may have realised by now, my reading friend, I am a bit of a wing nut. I know, it’s embarrassing. Now that the Felis catus has exited the proverbial container made of flexible material with an opening at the top, used for storing / holding / carrying things, let me add that I feel a certain fondness for some specific types of flying machines. The Fleet Model 50 Freighter bushplane happens to be one of them.

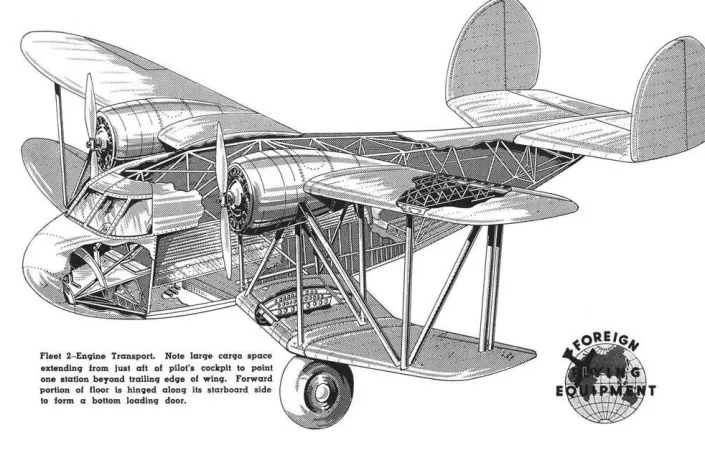

Fleet Aircraft of Canada Limited of Fort Erie, Ontario, started as a subsidiary of the American firm Consolidated Aircraft Corporation. Its creation came only a few months after the crash, in Ontario, of an aircraft piloted by the president of Consolidated Aircraft. London Aero Club instructor William John “Jack” Sanderson visited Reuben Hollis Fleet while he was in hospital. Impressed by the kindness of this complete stranger, Fleet hired him and put him at the helm of Fleet Aircraft of Canada. The first aircraft manufactured by the latter, a Fleet Model 2 light / private airplane, took to the sky in June 1930. A more powerful version, the Model 7, quickly replaced it on the assembly line.

Soon after, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) began to look for new elementary trainers and set up comparative tests. The Fleet Model 7 won, but the RCAF preferred to order the de Havilland Moth, a British aircraft. Furious, Sanderson traveled to Ottawa, Ontario, to meet with the Minister of National Defence. Donald Matheson Sutherland was so impressed that Fleet Aircraft of Canada signed a contract for 20 Fleet Fawns.

Not everyone was happy with this order. Several members of Parliament denounced the non-British origins of the Fawn. Sutherland finally had admit that this aircraft cost less than the Moth. Better yet, half of the materials used to make the Fawn, a rock-solid aircraft, came from Canada. This local content allowed Fleet Aircraft of Canada to circumvent tariffs imposed on non-British aircraft imported into Canada. It also opened up many markets outside the country. Indeed, it was largely for these reasons that Consolidated Aircraft had founded its Canadian subsidiary.

After its first government order was delivered, in April 1931, Fleet Aircraft of Canada barely scraped along. Its situation did not begin to improve until 1934. Anxious to modernise its air force, the Zhōnghuá Mínguó Kōngjūn, the Chinese government ordered 36 Fleet Model 10s, another derivative of the Models 2 and 7. For one reason or other, Consolidated Aircraft passed this order to its Canadian subsidiary.

In the spring of 1936, Fleet, the Homo sapiens of course, said he wanted to transfer all of his training aircraft export contracts to Fleet Aircraft of Canada. His intentions were clear. He wanted to bypass the ban on the export of weapons to countries at war which stemmed from the application of the American neutrality laws. This decision caused some concern at the Office of Arms and Munitions Control of the United States State Department. Be that as it may, tensions around the world meant that the Ontario aircraft manufacturer signed production contracts for Models 10 with countries in Latin America (Argentina, Dominican Republic, Mexico and Venezuela), Asia (China and Iraq) and Europe (Portugal and Yugoslavia).

It was also around that time, in November 1936, that an investment company, Nesbitt, Thomson & Company Limited of Montréal, Québec, took control of the firm which then became Fleet Aircraft Limited. In August 1938, it bought the last shares held by its former parent company.

With nearly 140 aircraft exported during the interwar period, Fleet Aircraft of Canada / Fleet Aircraft was the largest seller of aircraft in Canada at the time.

It was in this context that the subject of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, the aforementioned Freighter, came into being.

Recognising the growing importance of bush flying in exploiting the vast natural resources of Canada’s northern regions, the equally aforementioned Sanderson began to ponder how Fleet Aircraft of Canada could grab a slice of that cake. Indeed, he ended up concluding that a twin-engine bushplane, a twin-engine flying truck for all practical purposes, because what is a bushplane if not a truck with wings, could find a taker.

Sanderson contacted several / many bush pilots to find out what they thought of his idea. It was obvious that their opinions diverged. This being said (typed?), these pilots shared some points of view.

For example, Sanderson’s winged truck, the first aircraft entirely designed by Fleet Aircraft of Canada, would need to be able to take off from short liquid (lakes or rivers in summer) or solid (lakes or rivers in winter) runways. It would also need to have large loading doors. A small team would also need to be able to partially dismantle said aircraft in order to facilitate repairs or transport out of an isolated region.

With the Freighter far surpassing in size, power, weight and complexity any aircraft previously manufactured by the Ontario aircraft manufacturer, manufacturing the prototype took some time. Indeed, said prototype did not fly until February 1938. The aforementioned Sanderson was at the controls. Would you believe this was apparently his first flight in a twin-engine aircraft?

Regardless, the Freighter soon proved to have good flight characteristics, which led to the issuance of a temporary certificate of airworthiness in May.

This being said (typed?), the Department of Transport granted a full certificate of airworthiness to the aircraft only in September 1939, 4 days before Canada declared war on National Socialist Germany.

The prototype of the Fleet Freighter in its element. Canada Aviation and Space Museum, 2632.

The first Canadian twin-engine bush plane, the Freighter was a sturdy, somewhat stocky / chubby biplane with 4 large loading doors (2 on the left, 1 on the right and 1 underneath). The lower part of the nose could also be detached to facilitate the loading of particularly long items (drill rods, pipes, logs, canoes, etc.). Let us be blunt, the Freighter’s cargo loading facilities were unique for its time, regardless of whether that loading took place in a well-equipped airport or on a lake, summer or winter.

And yes, the Freighter could obviously be fitted with wheels, skis or floats.

Fleet Aircraft said it was ready to produce various versions of the Freighter for transport (passengers, cargo or casualties), aerial photography or light bombing. These versions could obviously be fitted with more or less powerful engines.

A fairly serious snag was that Fleet Aircraft, a relatively small firm (around 520 employees in 1939) let us not forget, had other fish to fry, a violent expression I shall endeavour not to use again, in 1938-40. After producing 20 Fawns for the RCAF in 1936-37, it delivered 11 other aircraft of that type in 1938, not to mention 27 examples of an improved version, the Fleet Finch, delivered between October 1939 and February 1940. To that list at that time were to be added a few export contracts for similar aircraft.

Worse still, in 1938, Fleet Aircraft began designing a modern intermediate / advanced trainer which it hoped to sell to the RCAF. The prototype of this internally funded aircraft, the Fleet Model 60 Fort, flew in March 1940, but I digress.

In the spring of 1938, Sanderson flew from Ottawa to Winnipeg, Manitoba, to show the prototype of the Freighter to bush pilots in Ontario and Manitoba. Indeed, he apparently carried cargo and / or a few passengers picked up along the way.

As the Freighter flew over Sioux Lookout, Ontario, Sanderson noted that the fabric cover on one wing did not appear to be tight. Once back on the water, very cautiously, he realised with horror that the bolts which attached at least 2 of the 4 wings to the fuselage were loose. This incident apparently stemmed from the improper installation of a new type of self-locking nut at the Fleet Aircraft plant.

Once the problem was resolved, a Winnipeg bush flying firm, Wings Limited, borrowed the Freighter to transport a dragline excavator in pieces to the construction site of a small hydroelectric power station. While it was true that only the Freighter could transport the largest element of said excavator, the lack of power and reliability of its engines, not to mention its somewhat too high cost, led Wings’ management to give up initialing an order.

United Air Transport Limited of Edmonton, Alberta, leased the Freighter in July to manage a large postal contract between Vancouver, British Columbia, and the Yukon. The boss of the firm, the well-respected George William Grant McConachie, was so impressed with the Freighter that he considered ordering 3 or 4 such aircraft.

In mid-August, 10 or so days after the first direct mail flight from Vancouver to Whitehorse, Yukon, the Freighter’s airspeed indicator stopped working in fog and low altitude. The aircraft crashed near Lower Post, British Columbia, near the Yukon border. While no one on board was injured, the first Freighter would never fly again.

United Air Transport purchased the second Freighter and registered it in February 1939. The day after it was registered, McConachie was in Chicago, Illinois, to sign an insurance policy. All these beautiful people then went to the Chicago Municipal Airport to see McConachie fly to western Canada. When one of the engines was started, a backfire ignited the aircraft, which began to go around in circles. As it were, by a miracle, it did not hit any other aircraft. The second Freighter would never fly again. Utterly dismayed, McConachie did not want to hear about this aircraft type again.

The third Freighter did not fly much between 1939 and 1942. This being said (typed?), Canadian Airways Limited of Winnipeg operated this aircraft during the summer and fall of 1939, under a lease for purchase contract. Quebec Airways Limited of Montréal, a subsidiary / division of Canadian Pacific Airlines Limited, itself a subsidiary of a Canadian transportation giant, Canadian Pacific Railway Company, leased the Freighter in August 1942, again under a lease for purchase contract, and this to supply meteorological stations in northern Québec. An engine having suffered serious damage in mid-flight, Canadian Pacific Airlines sold the Freighter to the RCAF in October, after repairing it. The military planned to use the aircraft for a variety of roles, including the training of Canadian Army paratroopers.

Converted into a flying ambulance because this latter service wanted to use larger aircraft to train its aerial soldiers, the Freighter was put aside in May 1944. Labrador Mining and Exploration Company Limited of Montréal, I believe, bought the Freighter in June. A pilot ferried the aircraft to the region of Sept-Îles, Québec. At least one other pilot performed some freight transport flights in said region. About ten days after its sale, still in June, the Freighter was at Sandgirt Lake, Labrador. After 2 or 3 unsuccessful and slighting unnerving take-off attempts, the pilot and his 2 passengers ended up in a ravine. No one was hurt but the third Freighter would never fly again.

Dominion Skyways Limited of Rouyn, Québec, leased the fourth Freighter for about a month, in July and August 1939. The aircraft was then put in storage until August 1942. Canadian Pacific Airlines leased the Freighter for about a month to support the people who were building 1 of the 4 pipelines of the Canol Project – a titanic American construction project to secure oil supplies to Alaska and the provinces and states of the west coast of North America through a refinery constructed in Whitehorse for that very purpose.

Would you believe that little more than one year after the last pipeline was completed, in February 1944, the Canol project was shut down because it was now surplus to the American war effort? The mind boggles.

In any event, in October 1944, on the return trip to Fort Erie, the pilot of the fourth Freighter faced an engine failure in the sky. He landed (by a hair’s breadth?) on Lake Ontario, at Jordan Harbour, Ontario, halfway between Hamilton and Fort Erie. Once the faulty engine was replaced, the Freighter returned to its hangar, unless it was simply parked behind the Fleet Aircraft factory. In May 1945, the aircraft manufacturer sold the Freighter to Austin Airways Limited, a bush operator headquartered in Toronto, Ontario, for a fraction of its value. When one of the engines was started in October 1946, at Lake O’Sullivan, in Ontario, a backfire ignited the aircraft. The fourth Freighter would never fly again.

The RCAF took delivery of the fifth Freighter in November 1942. The military planned to use this aircraft, manufactured but not assembled in 1939, for a variety of roles, including the training of Canadian Army paratroopers. Used for transport flights because this service wanted to use larger aircraft to train its aerial soldiers, the Freighter was put aside in August 1944. A well-known American aircraft dealer, Charles H. Babb Company, acquired it that same month and sold it to its Mexican subsidiary, Babbco Sociedad Anónima. Sold in October to Compañía Constructora Azteca Sociedad Anónima de Ciudad de México, México, a firm specialising in the construction of airports, the Freighter was dismantled / scrapped in March 1946. The fifth Freighter would never fly again.

There was no sixth Freighter.

Several bush pilots who flew the Freighter agreed that this aircraft had a lot to offer. While it was true that the somewhat too high cost of this aircraft and the priority given to RCAF orders explain its commercial failure to some extent, the bulk of the problem lied in the lack of power and reliability of its Jacobs engines, the (in)famous “Shakey Jakes.” Although aware of this serious problem even before the end of 1936, the management of Fleet Aircraft of Canada / Fleet Aircraft took no serious steps to remedy it.

This being said (typed?), I have to admit that, even with more powerful and reliable engines, the Freighter would probably not have been a dangerous rival for its Canadian contemporaries, the excellent Fairchild Model 82 and Noorduyn Norseman bush planes – an aeronautical dynamic duo represented in the mirific collection of the equally mirific Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa. In service since 1935 and 1936, the Model 82 and Norseman were produced in 24 and 22 examples before the start of the Second World War.

Before you go about your business, I must inform you that the Canada Aviation and Space Museum has in its collection the remains of 2 Freighters:

- the third one, the remains of which were recovered in 1964, with the blessing of Labrador Mining and Exploration, and

- the fourth one, the remains of which were recovered in 1968.

These remains are all we have to remind us of an aircraft which could have been, perhaps, one of the great bushplanes of the 20th century.

Hasta la vista, mi amigo lector.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)