A great lady who never let go of the potato: Anne Marie Harmonia Hallé and the Dulac potato chips saga

A big hello, my reading friend, and welcome to the world of technology and science, space and aviation, and food and agriculture – and serial / Oxford / Harvard commas. (Hello, EP!) It is through the third dynamic duo of the sentence before the previous sentence that yours truly hopes to titillate your little gray cells on this day.

Do you like potato chips? I have to admit that I have a thing for the junk food that potato chips are, a food high in calories, err, joules, with little nutritional value.

You will of course recall that the unit of the International System of Units, which is the modern iteration of what is commonly known as the metric system, used to measure energy is the joule, a unit named after the English physicist and brewer James Prescott Joule, not the calorie. We have been there before, you know. Keep up. If yours truly may paraphrase, out of context, the utterly possessed cello player Dana Barrett in the very popular 1984 (!) supernatural comedy motion picture Ghostbusters, there are no calories, there are only joules. Sorry, sorry.

Joule was of course mentioned in February and April 2023 issues of our essential blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to our potato chips.

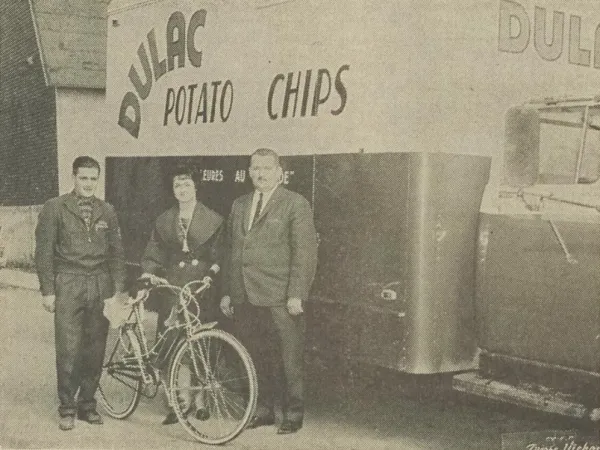

The photograph offered to your eyes comes from / came from a weekly newspaper, Le Peuple, published in Montmagny, Québec. We can see a smiling Mrs. Élie Fortin from Montmagny accepting the bicycle won by her daughter, Michèle Fortin, as part of a contest organised by Dulac Potato Chips Incorporated of Sainte-Marie / Sainte-Marie-de-Beauce, Québec. The person who gave her said bicycle was Fernand Labrecque. That Dulac Potato Chips district manager was on the right side of the photograph. The person on the left side of the photograph was a salesperson of the firm, Jean Claude Tremblay.

Yours truly acknowledges that the presentation of a bicycle in Montmagny in May 1963 was / is not as significant an event as the fall of an apple allegedly observed in 1665 or 1666 in England by the brilliant, pompous, quarrelsome and revengeful English theologian / physicist / mathematician / author / astronomer / alchemist Isaac Newton, a fall which would inspire the development of the theory of gravity.

Yes, yes, you read correctly, the theory of gravity. In science, a theory is an organised set of rules, principles, laws, knowledge and assumptions aimed at describing and explaining a set of facts. Just think of the theory of relativity or the theory of evolution. Relativity is an undeniable fact of a physical nature and evolution is an equally undeniable fact of a biological nature, but back to our Montmagnian bicycle.

As banal as the presentation of that bike was / is, it opens the door wide to a look, very short it has to be admitted, on a pioneer in a sector of the Canadian agri-food industry.

Our story began with the birth, in July 1899, in Lewiston, Maine, of Anne Marie Harmonia Hallé. At the end of December 1927, in the United States, that young woman tied the proverbial knot with a Quebecer, Joseph Éphrem Viateur Dulac. She soon moved to Québec with him, and… Yes, the province, not the city.

Did you know that the grandfather of Hallé’s spouse was the great-grandfather of the spouse of an older sister of my late mother? Ours is a small world, is it not, especially in Québec? Let us not forget, virtually all “old stock” francophone Quebecers, to use a somewhat loaded expression, all 6.75 or so million of them, have one or more than one common ancestors. How could it be otherwise given that the population of New France in 1763, when that French colony became a British possession, hovered around 70 000 people? Hi, cousin!

Our story continued with very sad news, however: the death of Dulac, then a businessman (travelling salesman?), in December 1943, at the age of 43. His spouse found herself the head of the family with 4 minor sons in her care. She was 44 years old and had never worked outside the family home. Dulac, the name I will use from now on to identify her if you do not mind, was obliged to quickly find sources of income.

According to family lore, the destiny of the Dulac family changed following one of the summer visits made by Rosaire Hallé, one of the grieving widow’s brothers, and his family. During that visit, in 1947, I think, Hallé traveled to Lévis, Québec, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, in order to take one of the ferries of Traverse de Lévis Limitée of Québec, Québec, which ferried across that majestic watercourse to go to Québec, yes, the city, not the province, on the north shore of said watercourse. During that brief trip, Hallé bought a bag of potato chips which he gave to his two daughters. The latter found that these potato chips were not at all fresh, or edible.

The putting of these potato chips in a trash can resulted from the fact that this product was not yet very popular in Québec. Yes, the province – but also the city. The little bags they were in, wax paper bags it seemed, quite often spent more than a little time on a shelf. Mind you, the waxed paper might also have let some moisture through, which would have made the potato chips a lot less crispy. Especially if you bought them on a ship.

Incidentally, it was to an American businesswoman, Laura Scudder, born Clough, founder of Scudder Food Products Incorporated, that humankind owed the idea of using wax paper bags to preserve the freshness of potato chips. That lightbulb moment came to her around 1926. Before that date, potato chips were generally stored in cracker barrels or glass display cases. A clerk gave them, err, sold them, to customers in paper bags, and… Yes, the potato chips were in the bags, not the customers.

Would you believe that Scudder Food Products was the first potato chip manufacturer to include a best before date on its packaging? The tagline which accompanied said date read: “Laura Scudder’s Potato Chips, the Noisiest Chips in the World.”

Before I forget, the first cellophane potato chips bags appeared, in the United States, no later than 1949, but back to the visit to Sainte-Marie of Dulac’s brother.

Back in that village, Hallé’s daughters were quick to tease their cousins because of the poor quality of Québec potato chips. Amused by what he heard and saw, Hallé turned to his sister and asked her why she could not produce good quality potato chips like the ones sold in their home state of Maine.

Herstory did not / does not say whether Dulac considered the idea excellent or wacky. This being said (typed?), she decided to embark on that adventure. One of Dulac’s sons, the oldest in all likelihood, Cyrille Roland Dulac, traveled to Maine and spent several months of the winter period of 1947-48 on the staff of a potato chip producer in that American state. Indeed, he explained to his superiors the reason for his stay. They did not seem to mind.

While said son was learning the ropes, Dulac ordered from the United States the equipment that she and her family would need: a peeler, a slicer and a stove. All that stuff was installed in a shed on the grounds of the family home.

The production of Dulac potato chips began in May 1948. All members of the family got their hands dirty. The initial selling price of the bags of potato chips, 10 cents, being deemed too high, Dulac had to… slice it in half. The agreements concluded with merchants of Sainte-Marie and Saint-Georges, a small city nearby, could not be clearer: any bag not sold after 2 weeks would have to be bought back by Dulac, in order to ensure the freshness of the product. Two of the brothers delivered the bags of potato chips made and wrapped by hand using the old family automobile.

Dulac and her sons might, I repeat might, have processed 275 to 340 kilograms (600 to 750 pounds) of potatoes into potato chips a day. These were packaged the next day and delivered the day after that. Business was so good that Dulac had the means to buy a small truck around 1949-50.

A hard blow fell on the Dulac family in August 1948: one of the brothers died. Viateur Clément Dulac was not yet 16 years old.

A turning point in the history of Dulac potato chips was an agreement with the aforementioned Traverse de Lévis. The sale of said potato chips on the ferries of that firm made them known both in Lévis and Québec.

The Dulac family had to deal with a major problem, however: the potatoes produced in the province of Québec around 1948 blackened and / or burned when placed in a fryer, or so I read. American potatoes were much better suited for potato chip production.

The problem was that Canadian potato exports to the United States had reached such a level in the fall of 1948 that the American government informed its Canadian counterpart that it was going to block those imports in order to prevent a fall in the price of tubers produced on American soil. Not wishing to start an agricultural conflict with its powerful neighbour, the federal government decreed an embargo on Canadian potato exports which came into effect in December. This embargo was lifted in June 1949.

That somewhat tense situation might have indirectly affected for a time the supply of American potatoes to Dulac’s fryer. This being said (typed?), the small firm grew little by little. Sadly, a fire destroyed the Dulac family factory and warehouse in May 1953. These facilities were soon rebuilt.

Known as Dulac Potato Chips Incorporated from March 1953, the firm might, I repeat might, have been known as Sainte-Marie Potato Chips Incorporated before that date.

Anne Marie Harmonia Dulac, born Hallé. Joseph Alphonse Fortin, editor. Biographies canadiennes-françaises. 18th edition. (Montréal, 1960), 246.

And no, yours truly very much doubts that Joseph Alphonse Fortin, a lawyer, publicist and editor who lived in Montréal, Québec, was closely related to the aforementioned Élie Fortin of Montmagny.

Regardless, Dulac Potato Chips continued to grow over the years. Charles Maurice Dulac bought the potatoes. Gérard Cyrille Dulac supervised their transformation into potato chips. Cyrille Roland Dulac, the vice-president of the firm, sold the latter. Their mother was the president of Dulac Potato Chips. And yes, you are right, my perceptive reading friend, Dulac was one of the few important businesswomen in Québec during the early post Second World War period. Indeed, she was then the only female firm president of the association of North American potato chip producers, the National Potato Chips Institute.

Would you believe that this American organisation, which later became the Potato Chip Institute International, held its first meeting on Canadian soil in late August, early September 1948? The Canadian organiser of that visit was Joseph Ena Houle, the founding owner of Laviolette Potato Chips Incorporated of Trois-Rivières, Québec. That potato chip producer, active since 1929, was initially known as Three Rivers Potato Chips Incorporated, I think. Anyway, let us move on.

Dulac Potato Chips acquired a smaller competitor in November 1961. The brother of Dulac mentioned above, Rosaire Hallé, took over the management of… Laviolette Potato Chips. I kid you not. The latter, however, continued its activities without changing its name.

Would you believe that Houle might, I repeat might, have been from Sherbrooke, Québec, the homecity of yours truly? Ours is a small world, is it not?

Before I forget, you will have noticed the use of English names for these firms founded and run by francophone Quebecers. The use of an English name might, I repeat might, have been seen as a guarantee of superior product quality, which was / is a bit sad in a province where the vast majority of the population, approximately 80%, was francophone – and often unilingual.

In September 1963, Dulac Potato Chips changed its name to Dulac Incorporée. It was / is a safe bet that it was from this moment, or just after it, that the French word croustilles appeared on packages of… croustilles, accompanied of course by the English term potato chips. The appearance of the word croustilles seemed to have had a positive impact on sales. You see, in 1963, it was only found on bags of Dulac potato chips.

The change of name of the firm and the use of the word croustilles were linked to the nationalist breezes which were blowing almost everywhere in Québec following the dissolution of the lead blanket represented by the government of the political party founded by Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis, a dissolution which followed its defeat at the general election of June 1960. You will of course remember that this right-wing man was often mentioned in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since January 2018.

In 1968, Dulac could count on 20 or so warehouses located between Chambly, Québec and Saint John’s, Newfoundland, and 125 or so trucks circulating throughout Eastern Canada – all the way to Ottawa, Ontario, in fact. Curiously, Dulac potato chips did not seem to be available in Canada’s metropolis, Montréal. Would you know why, my reading friend with immeasurable knowledge?

Year in, year out, Dulac transformed no less than 17 000 metric tonnes (about 16 750 Imperial tons / nearly 19 000 American tons) of potatoes into potato chips. A very important part of that intense work was carried out in an ultramodern factory inaugurated in November 1967 in Lauzon, Québec, not far from Lévis. Indeed, the Sainte-Marie factory closed its doors in October 1969. The small factory in Trois-Rivières had closed its doors in September 1965.

To the surprise of many, Frito-Lay of Canada Limited of Port Credit, Ontario, the Canadian subsidiary of an American potato chip giant, Frito-Lay Incorporated, itself a subsidiary of another American giant, Pepsi-Cola Company, acquired Dulac at the very beginning of June 1970. The age of the founder, the salary and other demands of the employees’ union, not to mention the high cost of potatoes and cooking oil, explained that decision.

This being said (typed?), Cyrille Roland Dulac continued to manage sales for the new subsidiary of Frito-Lay of Canada. His mother, on the other hand, participated from time to time in public relations campaigns, and this until around 1973.

Anne Marie Harmonia Dulac passed away in August 1991, at the age of 92.

The sale of bags of Dulac potato chips continued until at least 1995.

Curiously, I feel a tad peckish. Want to share an orange and white bag of Honeydukes roasted chimera potato chips? I hear they are quite popular at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)