“The bomb that will kill the porpoise” – A shocking use of air power in interwar Québec: The bombing of the beluga whales of the St. Lawrence River, part 3

Allow me to welcome you without further ado to this 3rd and penultimate part of our article on a shocking use of air power in interwar Québec, namely the bombing of pods of beluga whales which lived in the waters of the St. Lawrence River.

Yes, yes, the 3rd and penultimate part. Yours truly preferred to subdivide his text into 4 parts of reasonable length instead of 3 parts of unreasonable length. You are welcome.

Without further ado, let us begin our weekly reading.

As the beluga whale hunting season approached, a Montréal weekly, Le Bulletin des agriculteurs, mentioned in a January 1929 issue, words translated here, that

According to some experts it is believed that it was the Eskimos [sic] who chased the porpoises [sic] from the solitudes of the waters of Hudson Bay and the Ungava. The savages [sic] make noise to scare those animals. If that means is worth something, adds Mr. Perrault, we will use it to chase them north.

The mind boggles.

And yes, the French word sauvages, in English savages, was commonly used in Québec until the 1940s, if not the 1950s, to describe the first Nations and the Inuits. The word Eskimos, in French Esquimaux, in turn, was used until at least the 1970s, if not later.

A cooperative of Québec fishermen called on a likely more effective hunting approach around February 1929. The Scottish Canadian aviator Colin Spencer “Jack” Caldwell, then on his way to Newfoundland where he was to guide the fleet of ships involved in the seal hunt, made a brief stop on the North Shore. Yours truly unfortunately does not know if the flight(s) he carried out, if any, were successful.

And yes, that Caldwell is the one which was mentioned in the 1st part of this article.

Incidentally, the aforementioned Perrault was the Minister of colonisation, mines and fisheries of Québec, the lawyer Joseph-Édouard Perrault.

At the beginning of March 1929, during the examination of the budget of the Ministère de la Colonisation, des Mines et des Pêcheries du Québec, Perrault answered several questions relating to the depredations of beluga whales, repeating again that 100 000 or so of those cetaceans haunted the waters of the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River.

In response to a speech presented a few days later by the government member who represented the people of Québec’s North Shore, the lawyer Edgar Rochette, a member of the official opposition, the lawyer Albéric Blain, asserted that beluga whales consumed 2 or so million metric tonnes (2 or so million imperial tons / 2.2 or so million US tons) of fish per year. Which amounted to saying that Québec’s beluga whales consumed more than 4 times more fish than all Canadian fishermen caught in 1929. I kid you not.

As we saw in the 1st part of this article, that was a totally ridiculous figure. It would in fact have required the presence of 250 to 300 000 beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. The total number of those cetaceans in that region of the world was actually 25 to 40 times smaller.

Where the heck did Blain get that absolutely laughable figure, you ask, my flabbergasted reading friend? I do not have the foggiest idea.

Dare I state that you and I know of recent examples of politicians who claim to base their statements on solid scientific evidence when, in fact, they ignore reality to defend an ideological point of view whispered by who knows who? You are probably right, my reading friend, I will not dare.

And yes, Rochette continued to implore Perrault to do something. Some of his voters were indeed starting to get impatient.

Approached in March 1929 by the daily La Presse of Montréal, Québec, the secretary of the Association des Gaspésiens de Montréal, editor of the Montréal weekly Le Bulletin des agriculteurs and founding president of a cannery, Le Poisson de Gaspé Limitée of… Mont-Louis, Québec, Firmin Létourneau happily agreed to be interviewed. Yes, the Létourneau mentioned in the 2nd part of this article. The beluga whale scourge was obviously among the topics discussed.

Since Québec fishermen were equipped for cod fishing, an activity that they knew well, and not for beluga whale hunting, Létourneau did not believe that they should abandon the first in favour of the second. However, he recognised the usefulness of getting rid of that cetacean.

To do that, Létourneau suggested blocking their passage at the Cabot Strait, 110 or so kilometres (70 or so miles) wide, between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. According to him, a systematic bombing of beluga whale pods would make it possible to achieve that objective. The federal government, responsible for fisheries in the Îles-de-la-Madeleine and the Maritime provinces, could undoubtedly support that effort, presumably through the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Indeed, as the spring of 1929 ended, the new Minister of colonisation, mines and fisheries of Québec, Hector Laferté, supervised the preparation of an action plan. He decided to offer a reward for each beluga whale killed in the estuary or gulf of the St. Lawrence River.

To facilitate beluga whale hunting, the Ministère de la Colonisation, des Mines et des Pêcheries du Québec purchased several hundred special rifles which it made available to fishermen under good conditions.

To answer the question which was condensing into your little noggin, Laferté’s arrival at said ministry occurred during a cabinet shuffle, in April 1929. That change was largely due to the failing health of Joseph-Édouard Caron, Minister of agriculture since November 1909 and member of the Conseil législatif du Québec, the province’s senate for all intent and purposes, an institution abolished in December 1968.

One of the beluga whales captured and killed by Joseph Lizotte’s team, Rivière-Ouelle, Québec. Anon., “-.” L’Action catholique, 13 June 1929, 1.

It went without saying that hunts organised by people such as Joseph Lizotte, a resident of Rivière-Ouelle, Québec, mentioned in the 2nd part of this article, could contribute to the success of the enterprise.

Indeed, with the support of 25 or so farmers from the Rivière-Ouelle region, Lizotte captured and killed nearly 190 beluga whales in May 1929, using traps placed along the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. He hoped to make a profit of about $6 000 from that catch, a sum which corresponded to about $105 000 in 2024 currency. Lizotte obviously hoped to increase his catches throughout the summer.

Rumours also began to circulate, in June, I think, according to which the Ministère de la Colonisation, des Mines et des Pêcheries du Québec had secured the services of a small air transport firm, one of whose seaplanes would be used to bomb beluga whales. The objective here would perhaps be not so much to kill them but rather to disperse them in order to facilitate the task of hunters operating from longboats.

You will of course remember, my reading friend, that the person chosen to lead the investigation aimed at finding ways to get rid of the beluga whales, the American zoologist Glover Morrill Allen, had concluded in a report that it would not be practical to bomb beluga whales, but back to our story.

A representative of the ministry, Eugène Comeau, went to the North Shore around the beginning of July to organise the capture of the beluga whales, using nets or other means.

The rumours regarding the bombing of the beluga whales were soon confirmed.

Having just returned from a brief stay on the North Shore at the beginning of July, Laferté announced the signing of a contract with Laurentian Air Express Limited of Québec, Québec. The minister also announced that a flotilla of 50 or so small boats carrying armed men would launch an attack on the beluga whales, under the direction of the aforementioned Comeau, who had set it up.

A telegraph station installed for the occasion in Saint-Joseph-des-Sept-Îles / Seven Islands, today’s Sept-Îles, Québec, the largest municipality on the North Shore, I think, would signal the passage of the cetaceans to the residents of the main localities of the region.

Laferté concluded his announcement by stating that if that two-pronged attack aimed at getting rid of the beluga whales without exterminating them did not give satisfactory results, he would have no other choice than to commercialise the hunt of those animals by forming cooperatives and distributing subsidies. That hunt would be done using nets, or traps similar to those used by Lizotte, and…

You are right, my reading friend. It is time to dive into the heart of our topic.

Laurentian Air Express was a brand-new entrant in the Québec / Canadian air transport industry. That small firm had actually come into existence in April 1929.

Its president was Louis Cuisinier. Yes, yes, that Cuisinier. The technical director of a small air carrier, Canadian Transcontinental Airways Limited of Montréal, who was among those who had flown to the rescue of the crew of the Junkers W 33 Bremen which, in April 1928, had landed as best it could on Greenly Island, a small Québec island located at the entrance to the Strait of Belle-Isle, very close to Blanc-Sablon, Québec, and the Québec-Labrador border.

Why did said crew land on that pebble, you ask, my perplexed reading friend? Would you believe that neither the aircraft’s German pilot and owner, Hermann Köhl and baron Ehrenfried Günther von Hünefeld, nor its Irish navigator, James Michael Christopher Fitzmaurice, knew where they were after completing the first east-west crossing of the Atlantic Ocean?

Yours truly must admit to having found no information on the early years of the Franco-Canadian physician / pilot and First World War veteran that Cuisinier was.

This being said (typed?), a Louis Cuisinier completed a thesis at the Faculté de médecine et de pharmacie of the Université de Lyon, in… Lyon, France, in 1903. A person with that same last name was for his part a student at the École du Service de Santé Militaire de Lyon, I think, that same year 1903.

In any event, Cuisinier apparently served in the French armed forces during the First World War.

The good doctor and his family immigrated to Québec, yes, the province, at some point after the end of the conflict. Cuisinier first appeared to practice medicine in the Lac Saint-Jean region. He moved to Québec, yes, the city, with his family no later than 1925. A small advertisement published in November in a major daily newspaper of that city, Le Soleil, attested to his presence. And here is most of its content, translated here:

Doctor Louis Cuisinier

Obstetrician from the faculté de Paris, former extern at Lille hospitals, decorated with the Croix de Guerre, has the honour to announce that he is based in Québec – 44, St-Louis Street.

A former student of the medical clinic for sick children and maternity wards in Paris, Doctor CUISINIER will be particularly interested in the illnesses of children and women.

While it was true that Cuisinier had held the position of technical director of Canadian Transcontinental Airways around 1927-29, he was certainly not director of any Dominion topographical and aerial survey office, as a newspaper article suggested at the time. This being said (typed?), Cuisinier’s participation in the rescue of the crew of the Bremen had made him a local celebrity.

Incidentally, in late December 1927, Canadian Transcontinental Airways had launched the first regular (biweekly?) airmail service to the North Shore, and this between Saint-Étienne-de-Murray-Bay, today’s La Malbaie, Québec, and Saint-Joseph-des-Sept-Îles, and this via Anticosti Island, also in Québec. The aircraft’s initial starting point was the good city of Québec.

What used to take 3 or so weeks in winter, with dog teams, could now be done in 3 or so hours. Incidentally, would you believe that bags of mail destined to villages located along the way were seemingly pushed out the door without the benefit of a parachute? The deep snow was deemed sufficient to cushion their fall. I kid you not, but I do digress. A lot. Sorry.

Before undertaking his bombing campaign, Cuisinier carried out a few test flights around mid-July 1929, aboard one of his firm’s first operational aircraft, a small German Klemm L 25 floatplane or, more precisely, an AKL-25 manufactured under license in the United States by Aeromarine-Klemm Corporation. And yes, some explosive charges or handmade bombs were dropped from the air.

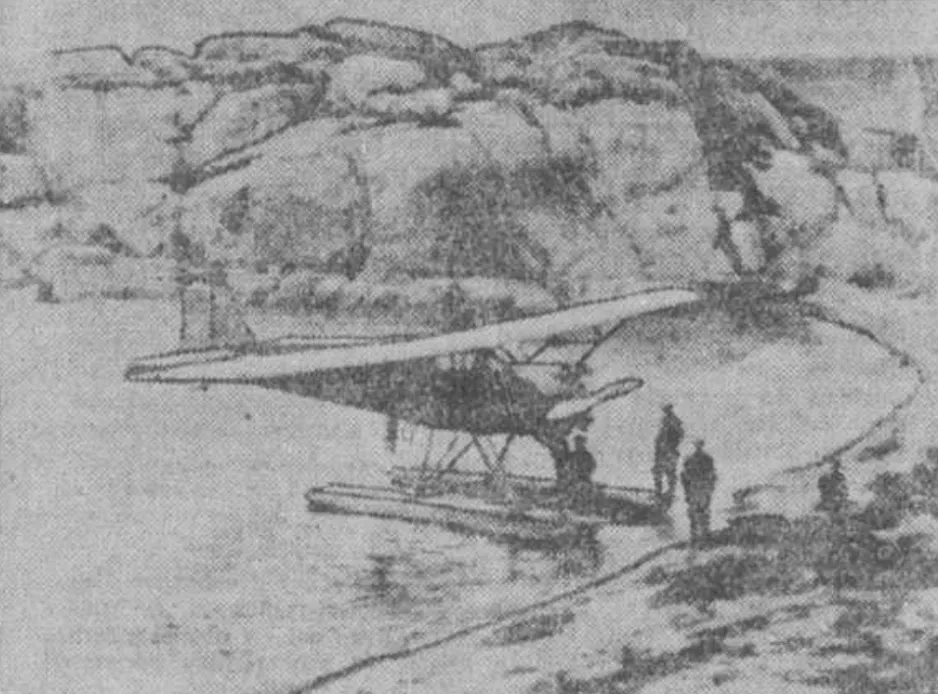

The Curtiss-Robertson Robin used by Laurentian Air Express Limited of Québec, Québec, to bomb the beluga whales inhabiting the waters of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “Le marsouin est un cétacé très difficile à détruire.” La Presse, 16 November 1929, 39.

Cuisinier went to Montréal, to the Curtiss-Reid Aircraft Company Limited factory more precisely, towards the end of July, to take delivery of the Curtiss-Robertson Robin floatplane purchased at the beginning of that month by Laurentian Air Express. He soon returned to Québec, yes, the city, where, it was said, 3 other aircraft which were to participate in the expedition were waiting for him.

Given that Laurentian Air Express owned a grand total of 2 aircraft at the time, the Robin and the aforementioned AKL-25, one might surmise that news reports were inaccurate, or that another firm would be lending a hand to Cuisinier’s firm. Your guess is as good as mine.

And yes, my assiduous reading friend, Curtiss-Reid Aircraft, a subsidiary of the recently created American aeronautical giant Curtiss-Wright Corporation, was indeed mentioned in several issues of our memorable blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2019.

And yes, again, Curtiss-Wright was mentioned on moult occasions in that same publication, and this since November 2017, but I digress. Your fault.

Intrigued by what was brewing, the management of an influential Canadian daily, The Toronto Daily Star of… Toronto, Ontario, sent one of its journalists to the North Shore. Contrary to what he had hoped, Allan Gordon Sinclair had to get there by ship, and...

Yes, yes, that Sinclair. The one who was a panelist on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) television program Front Page Challenge between June 1957 and his death in May 1984. In case you did not know, Front Page Challenge was a news and history game show which aired from June 1957 to February 1995, but I digress.

Need yours truly mention that the CBC was mentioned a great many times in our you know what, and this since September 2018? I thought so. Let us move on.

Would you believe that Sinclair (seriously?) claimed to have met the great Swedish film actress Greta Garbo, born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson, on an ocean liner anchored in the port of Montréal, around August 1929? In that regard, it should be noted that, over the years, various people expressed doubts about the veracity of certain incidents reported by Sinclair.

To answer your inevitable question, the supremely popular Garbo apparently showed up in Montréal only once, in late October 1936. She managed to travel undetected from one train station to another, leaving in her wake a pack of frustrated journalists, but I digress.

Approached by Sinclair, Cuisinier stated that the bombing of beluga whales which would begin shortly in Québec was inspired by the bombing which had taken place in Norway, Sweden and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Indeed, the good doctor stated again, it was the success of those bombing campaigns which had driven beluga whales to the waters of the St. Lawrence River.

How had Cuisinier come to that conclusion, you ask, my sceptical reading friend? Well, he asserted that hundreds of beluga whales had been tagged during the bombing campaigns of Northern Europe. Some, if not many of those animals were now showing up in the St. Lawrence River.

Was there any truth to those statements, you ask, my reading friend eager for answers? Or was Sinclair fabulating? Yours truly has no idea but the lack of evidence certainly creates some doubts.

The bombing campaign, dare I say the war declared on the beluga whale, began a little after the beginning of August, a little later than planned it seemed, with Cuisinier’s departure towards Saint-Joseph-des-Sept-Îles. Cuisinier actually took off in the company of two Laurentian Air Express pilots, Édouard Octave “Fizz” Champagne and J. Armand Gagnon.

As you know very well, Champagne, then chief pilot of the firm, was mentioned in a September 2023 issue of our exceptional blog / bulletin / thingee.

In parallel with said bombing campaign, no fewer than 230 to 250 fishermen armed with rifles set out to attack the pods of beluga whale. They might have been using weapons provided by the Ministère de la Colonisation, des Mines et des Pêcheries du Québec. Their ammunition actually came from that ministry.

Do you have a question, reading friend? Why was the launch date of the bombing campaign a tad delayed? A good question. You see, Cuisinier had to take care of 15 or so applications at the École aéronautique de Québec that Laurentian Air Express had launched in July in the parish municipality of Sainte-Foye, Québec, a stone’s throw from Québec, yes, the city. More than 50 people were already taking courses, a total which impressed more than one person in the Québec region.

After several reconnaissance flights carried out on the North Shore, Cuisinier came to the conclusion that Havre-Saint-Pierre, Québec, a village located 220 or so kilometres (140 or so miles) east of Saint-Joseph-des-Sept-Îles, would constitute the most appropriate base of operations.

It did not take long for a hangar to be set up to safely accommodate the handmade bombs which would be used to cull the pods of beluga whales, and this possibly under the supervision of a qualified employee of Canadian Explosives Limited of Hamilton, Ontario.

The 45 or so kilogramme (100 or so pounds) handmade bombs used during the attacks were in fact supplied by that manufacturer of explosives / coated fabrics / paints / plastics / varnishes. They arrived on site by ship, with all the equipment (fuel, oil, etc.) that Cuisinier and his team needed. One of the said ships was SS North Shore, the ship of the British firm Clarke Steamship Company Limited which served the North Shore. The second was an unidentified schooner.

It should be noted that Cuisinier and the other pilots had difficulty detecting the pods of beluga whales which, it was said, were constantly moving.

Dare I comment here that those difficulties were a tad difficult to understand given the claims that there were 100 to 150 000 beluga whales in the estuary and the gulf of the St. Lawrence River? Too controversial, you say again and again, my reading friend? Cannot a guy have an opinion?

The very day of the first attack, I think, L’Action Catholique, a hyper-conservative Québec, yes, the city, daily newspaper supported by the roman catholic church of Québec, no, the province, published an article on beluga whale hunting which contained a sentence, translated here, which was somewhat callous. You be the judge: “The provincial government has commissioned an aviator, Dr. Louis Cuisinier, to make if possible a fricassee of the populous colony of porpoises [sic] by bombing them from high in the air.”

The first attack was soon followed by several / many others. Cuisinier stated he was satisfied with the results. Indeed, fish catches seemed, I repeat seemed, to improve after just 4 or 5 attacks.

This being said (typed?), the handmade bombs were not as effective as expected. You see, they were equipped with a time fuse, allegedly lit with… a match, which caused their explosion 30 or so seconds after their impact with the waters of the St. Lawrence River. As you might imagine, beluga whales near the impact points apparently chose not to hang about to see what would happen, especially after the first explosion. They skedaddled as fast as their tails could carry them. As a result, the explosions hardly affected them, thought Cuisinier and his team.

In fact, those explosions were certainly very painful and damaging for animals with extremely fine hearing like beluga whales.

The aforementioned Sinclair was of the opinion that the bombing approach used by Cuisinier and his team was quite hazardous. Cuisinier and his team scoffed at such an idea.

In any event, Cuisinier asked for the delivery of new handmade bombs with impact fuses which would cause their explosion upon impact with the waters of the St. Lawrence River. And no, my cautious reading friend, those impact fuses would probably not have made the bombing approach used by Cuisinier and his team any less hazardous.

Sinclair flew at least once with Champagne and Cuisinier. Indeed, the journalist claimed that they left him high and dry in a village with no connection to the outside world after he had wandered off while the two men tweaked the engine of the aircraft. Thankfully, Champagne and Cuisinier came back and picked up a much-relieved Sinclair.

After a week spent on the North Shore, Cuisinier returned to Québec, yes, the city. A Laurentian Air Express pilot then left the city at the controls of a company aircraft, presumably the Robin.

Cuisinier soon found himself on the sidelines. You see, he broke an arm in an automobile accident a little before mid-August.

Questioned around that time by journalists, the Premier of Québec claimed to have received no news to share, other than the accident which had occurred at Cuisinier. Louis-Alexandre Taschereau added, however, that he was confident that the bombing of the beluga whales would be successful.

In any event, again, said bombing stirred the imagination of a member of the team of a Montréal humorous / satirical weekly, Le Canard. An August issue indeed contained the following lines, translated here:

Dr. Louis Cuisinier wages war on the porpoises [sic] which feed too gluttonously on the fish of the St. Lawrence.

If big fish eat small fish, it is like politics. Big deputies eat small voters.

A Montréal weekly, Le Petit Journal, threw a much bigger stone in the pond by publishing a text entitled, in translation, “Dr Cuisinier’s bombs on the porpoises [sic] might be money thrown down the drain” a little after mid-August.

An unidentified but apparently very cultured resident of the North Shore who, according to Le Petit Journal, seemed to know well the marine fauna of the St. Lawrence River and the French coast, asserted that the beluga whale was too smart to be easily overflown by something it had never seen and which seemed to be followed by explosions.

That resident, for whom Québec ministers, perhaps Taschereau and / or his ministers of colonisation, mines and fisheries, the aforementioned Laferté and Perrault, I cannot say, were suckers, went even further, words translated here.

And my doubts are so well shared by the people of the coast that, seeing emerging in the firmament, in his blood-coloured airplane, the Richthofen of the war on the ‘porpoise’, everyone burst out laughing. Tartarin hunting lions was no more successful.

[…]

Assuming that the aviator ever comes within firing range, the bomb which would kill a porpoise [sic] will perhaps annihilate a school of herring or sardines. In short, wanting to protect the fish by bombing the ‘porpoise’ with dynamite from the air is as if police officers looking for a pickpocket were first announced by a fanfare, then having, extraordinarily, flushed out the criminal, shot at him in the middle of a crowd of ten thousand people.

A detail before I forget it. The floatplane used against the beluga whales appeared to be orange, not red.

Having acquiesced to a question from the journalist that Cuisinier’s handmade bombs were, for all intents and purposes, money thrown down the drain, our resident asserted that the creation of a marine biology research station in the gulf of the St. Lawrence River would be far more useful. He added, however, that it would not be easy to convince simple politicians of the importance of research in the conservation and increase of the fish wealth of said gulf.

Beluga whales and fish came and went, stated the resident, words translated here; “Who is to say that the ‘porpoise’ question will not settle itself once again?”

It should be noted that this same resident mentioned that the term porpoise used by everyone actually seemed inaccurate. A typical porpoise was a small cetacean. The animal chased by Cuisinier seemed to be the beluga whales, he stated, which was entirely correct, as you and I noted in the first part of this article.

And you have a question, my reading friend? Who were the Richthofen and Tartarin mentioned in the article published by Le Petit Journal? A good question.

Baron Manfred Albrecht von Richthofen, the famous German Red Baron, active during the First World War and ace of aces in that conflict, was one of the great fighter pilots of the 20th century. We encountered him in several issues of our very peaceful blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since May 2029, uh, sorry, 2019.

And no, my patriotic friend, von Richthofen was not shot down, in April 1918, by a Canadian aviator serving in the Royal Air Force, Captain Arthur Roy Brown. He was brought down by an Australian machine gunner firing from the ground, but back to our story.

Tartarin or, more precisely, Tartarin of Tarascon was / is the main character in a series of 3 novels by the French playwright / writer Louis Marie Alphonse Daudet, published between 1872 and 1890. A plump, middle-aged Frenchman, Tartarin was a good egg, somewhat boastful, naïve and ridiculous. His first adventure took him to North Africa, to the French colonial territory of Algeria actually, for a lion hunt which ended with the death of a poor blind and elderly tame feline which certainly did not deserve such an end.

And it is on this sad literary note that the 3rd part of this article ends. Can I count on you to return here in a few days?

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)