Hauling freight on thin ice: The ice bridge railway between Longueuil, Québec, and Hochelaga / Montréal, Québec, Part 2

Welcome to the second part of this article on a unique aspect of the history of railways in Canada, my reading friend.

When we bailed last week, the ice railway between Hochelaga / Montréal, Québec, and Longueuil, Québec, had just been inaugurated, in late January 1880. Let us see what happened afterward, shall we?

On the first day of regular service, one or more trains carried people interested in experiencing the thrill of travelling on ice. The cost? 25 cents for a return trip, which amounted to about $ 7.00 in 2023 currency, which was / is not too bad. And no, had yours truly been present at the time, I would not have made that crossing for all the wealth on Earth. Am I a Gallus gallus domesticus, you ask, my amused reading friend? You bet.

By the way, you and I should consider ourselves lucky that chickens are the size they are. Meeting an aggrieved Gallus gallus domesticus the size of an adult Homo sapiens in a dark alley might not be a fun experience.

Which brings to mind Sylviornis, a not too, too distant relative of chickens. A native of New Caledonia, an island in the Pacific Ocean, that flightless bird, a slow moving browser from the looks of it, weighed up to 35 or so kilogrammes (75 or so pounds). With its head held high, a large individual would have been up to 1.6 metre (5 feet 3 inches) tall. Human predation as well as predation by packs of feral dogs, introduced by said humans, not to mention habitat loss resulting from the presence of… humans, caused the extinction of Sylviornis no more than 3 000 years ago. Pity. But back to our story.

As it turned out, the ice rail track seemingly began to carry trains consisting of freight cars and / or flat cars a couple of days after its inauguration. Deemed a tad too heavy, the locomotive used to inaugurate it might have been set aside in favour of a lighter machine. Indeed, steam power might have yielded to horse power on several / many occasions.

That was not the only setback, however. The limited facilities available at Longueuil were proving problematic. The time it took to unload the freight cars also greatly annoyed the management of Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway Company (QMO&OR) of Montréal (?), which had hoped to deliver more goods – and make more moolah. A very serious thaw in late February also caused some concern.

Incidentally, the thickness of the ice near the track was checked thrice a week. Holes were drilled every 180 or so metres (200 or so yards). As late as early March, the ice was up to 60 to 90 or so centimetres (2 to 3 or so feet) thick. This being said (typed?), however, a very large opening in the ice, only 180 or so metres (200 or so yards) away from the track, was steadily if slowly getting closer. To reduce the load on the ice, horse power replaced steam power in mid March.

The final crossing of the 1880 season took place on the very first day of April, and that was no joke. The track was soon dismantled and stored in Longueuil and Hochelaga, ready for use during the winter of 1880-81. Tragically, one of the workers hired for the job, a Quebecker by the name of Valiquette, lost his life when he slipped through the ice.

All in all, 1 000 to 1 200 or so railroad cars had made the crossing over a period of 2 months. Horses provided the required power in most cases. Had more railroad cars and a dedicated locomotive been available full time, a lot more freight could have been carried.

To make things worse, the ice railway lost money. This being said (typed?), the managements of QMO&OR and its partner, South Eastern Railway Company of Montréal, were generally happy with the results. You see, they had not expected to make money during the first season of operations.

And yes, in preparation for the 1880-81 season, one or both of the firms ordered 100 additional railroad cars.

It was also worth noting that the very existence of the ice railway might, I repeat might, have forced Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada (GTR) of Montréal to (significantly?) reduce its freight rates on the route between Québec, Québec, and Boston, Massachusetts.

Eager as ever to carry freight across the Saint Lawrence River, South Eastern Railway and QMO&OR seemingly used barges towed by a tug as soon as navigation between Hochelaga and Longueuil became possible. As a longer term measure, they planned to finance the construction of a pair of railway ferry steamers which were to be ready by August 1880. There was even talk of a tunnel.

And yes, my reading friend, it looks as if only one sidewheel railway ferry steamer, a ship seemingly known as SS South Eastern, was actually built, by Montreal Marine Works (Limited?), a respected Montréal shipyard owned by a leading francophone shipbuilder, Augustin Cantin. The firm which operated that ship was Compagnie de navigation de Longueuil.

Launched in July 1881, the railway ferry seemingly made its first trip across the Saint Lawrence River in September. Initially used to carry freight, the ship carried its first load of 4 loaded railroad cars that same month. Indeed, by the first week of October, SS South Eastern had carried no less than 400 railroad cars across the Saint Lawrence River. Put in a dry dock to repair some damage to its hull at some point in October or November, it was back in service well before the end of the latter month.

Before I forget, did you know that William Notman, the co-boss of the famous Notman & Sandham photography studio of Montréal was apparently the president of said Compagnie de navigation de Longueuil? Small world…

Oddly enough, the well known firm Beauchemin & Fils (Limitée?) of Sorel, Québec, operated by Joseph Hyacinthe, Louis Philippe and Moïse Beauchemin, was also mentioned as the maker of the sidewheel railway ferry steamer. Better yet, the pair of steam engines built for use on that ship was allegedly made by E.E. Gilbert & Sons (Limited?) of Montréal.

So what, you say (type?), my blasé reading friend? So what!? I will let you know that Ebenezer Edwin Gilbert was one of the first mechanical engineers, a self taught engineer for sure but still a pretty darn good one, who came into this world in what is now Canada. Actually, he was born in Montréal, in what was then Lower Canada, in September 1823.

Gilbert was recognised for the quality and innovative nature of the steam engines he developed for use in ships and municipal water pumping stations, not to mention his pioneering work in underwater drilling.

One only needed to mention the engine of the river paddle steamer SS Montreal, the largest and most powerful made thus far in what was then the Province of Canada. Completed in 1860, that ship was still making its regular runs between Montréal and Québec when Gilbert left this Earth in February 1889, at the age of 65, but back to our story.

The relative success of the 1880 season encouraged the promoters of the ice railway to try again during the winter of 1880-81. Indeed, construction of the track began in early January 1881 and was all but complete within days. If the ice on the Longueil side proved remarkably smooth and growler free, that on the Hochelaga side proved far more difficult to work with. Given the number of railroad cars awaiting at Hochelaga (up to 1 500?), speed was of the essence. Indeed, the workers worked by torchlight on at least two occasions. Louis Adélard Senécal and a few other bigwigs showed up at least once to encourage them to proceed quickly.

For some reason or other (good ice quality or need for speed?), the railway track installed across the Saint Lawrence River in 1881 was significantly shorter than the one used in 1880. Rather than make a large detour, its trajectory between Longueuil and Hochelaga was almost a straight line.

As beneficial as the new route would be for the operators of the ice railway, many individuals who frequently had to cross the Saint Lawrence River were far from happy. Said new route was at times uncomfortably close to the path taken by these individuals. The noise of locomotives could frighten the horses which towed their sleighs. If the municipal authorities of Longueuil did not look into that matter, they might be sued by whoever got into an accident caused by a freaked out horse.

A locomotive went on the ice in early January, before some finishing touches to the track were put in. It met up with up some railroad cars in the middle of the river and hauled them to a shore of the Saint Lawrence River I have yet to identify. Horses then left Longueuil and towed quite a few railroad cars to the middle of the river. A locomotive left Hochelaga not too long after and hauled said railroad cars to a shore of the Saint Lawrence River I have yet to identify. Convinced that the ice railway was ready for use, the team hitched a locomotive to 18 railroad cars, I think, and watched as it crossed the mighty Saint Lawrence River.

On that same initial day of operation, a train was but 180 to 280 or so metres (200 to 300 or so yards) from the shore at Longueuil when it jumped its track, rolled over on one side, crashed through the ice and sank. All but one of the several people on board had the time to heed the warning shouted by the fireman and jumped to safety on the ice. The engineer / train driver was not quite as quick. He fell in the water and was lucky to escape with his life.

Oddly enough, several news reports pointed out that one of the individuals aboard the locomotive, the fireman perhaps, was the son of the general superintendent of QMO&OR. This cannot be, as Senécal did not have a son. He did, however, have two daughters.

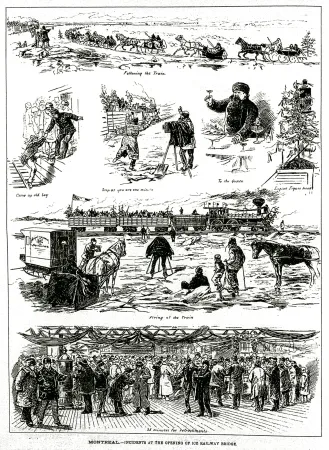

Various aspects of the accident which befell the ice railway between Hochelaga, Québec, and Longueuil, Québec. Anon., “Sketches on the ice railroad, a locomotive gone astray.” Canadian Illustrated News, 15 January 1881, 41.

While the cause… What is it, my reading friend? You wish to know more about the illustration you just saw? Music to my ears. Here come their captions…

Top left – Great excitement among the natives

Top – Map of the ice-bridge-railway, from shore to shore

Bottom – The accident

Yours truly took the liberty of excluding views of the site of the accident seen from a distance and looking toward both Hochelaga and Longueuil, as well as a drawing of three people checking the thickness of the ice, but back to our story.

While the cause of the accident could not be fully ascertained, it was possible that the train with the 18 railroad cars had weakened / cracked the ice. Mind you, a change in ice thickness and / or an eddy on the site of the accident which had affected the thickness of the ice might also have played a role.

The ice railway team soon put up a short passing track some distance away from the huge hole in the ice, which allowed traffic to resume the following day, I think. The new locomotive assigned to the ice railway soon broke down, however, which meant that horses had to be used for some time.

The toppling of a horse-driven lorry the day after the accident when its driver went up an incline to avoid a collision with a horse-driven sleigh showed how concerning the state of ice on the Saint Lawrence river was.

In the meantime, large amounts of water, not to mention plenty of hay and branches, were thrown around the gaping hole to strengthen its perimeter so that a trio of large cranes could be anchored near its edge. By the time this work was completed, the ice was 2.15 or so metres (7 or so feet) thick.

The team whose job it was to raise the locomotive was, it was said, headed by a local master carter, Louis Laurier, I think. This being said (typed?), a gentleman from Sorel, Québec, by the name of Charles or Moïse Champagne was in charge of the diving team. Wearing the heavy and cumbersome diving suit used at the time, the latter had to go down 3 times without success in the frigid waters of the Saint Lawrence River before coming across the QMO&OR locomotive, intact but lying on its side, in 9 or so metres (30 feet) of water.

Numerous gawkers looked at the proceedings with a great deal of interest, which annoyed and worried the people involved in the salvage operation. You see, if one of the cables used to lift the locomotive or one of the cables of the anchors used to stabilise the derricks was to fail, many of the gawkers could get seriously injured – or worse. Indeed, one the cables did fail later on as the locomotive was leaving its watery grave but, thankfully, no one was hurt. The team had the time to attach cables to the locomotive before it sank a second time to the bottom of the river.

A Montréal daily newspaper, La Patrie, found much it did not like about the reports published in the pro-government daily newspaper La Minerve, which was also Montréal-based. According to that non pro-government newspaper, three individuals by the name of Beauchemin, Fréchette and Seigman (Sigman? Seligman?) were in charge of the salvage operation. Seigman was the one who dove in the Saint Lawrence River. He actually needed to go down at least half a dozen times to secure the chains needed to lift the locomotive, which was not perfectly intact.

Oddly enough, La Patrie, reported that La Minerve had reported that the water at the bottom of the Saint Lawrence River was… warm. However, this was not correct. The latter claimed that divers claimed that the water temperature was comfortable.

In any event, the locomotive was hoisted out of the water in late January and towed to a shop in nearby Longueuil, using a temporary track. It was seemingly back on track, no pun intended, by the middle of February, and…

You have a question, do you not, my attentive reading friend? Wonderful. Please, speak. Was the Beauchemin person mentioned a few seconds ago one of the owners of the well known firm Beauchemin & Fils (Limitée?) of Sorel, Québec, operated by Joseph Hyacinthe, Louis Philippe and Moïse Beauchemin and mentioned in the first part of this article as a possible maker of the sidewheel railway ferry steamer SS South Eastern? Humm, I had not thought of that, but that was / is certainly a possibility. Good catch, but you are the one digressing this time. Back to the 1881 season of operation of our ice railway.

Mild and rainy conditions soon proved problematic for the operators of said railway. Cracks appeared in the ice. To maintain service, workers inserted long wooden beams under the track to spread the load. Horses were used instead of a locomotive to further reduce the load on the ice.

In March, as spring came upon Montréal, workers began to dismantle the ice railway. Every piece of it was gone and stored several days before the end of the month. All in all, the rail track on the ice had been in place, but not necessarily operational mind you, during 10 or so weeks.

Oddly enough, on that same day that spring came to Montréal, a Québec daily, Le Journal de Québec, reported that, not quite a month before, an ice railway had been inaugurated between Oranienbaum and the island port of Kronshtadt, two locations located near Sankt-Peterburg, Russian Empire. Le Journal de Québec seemed to think that the despatch it was quoting stated that said railway was the first in the world. Yours truly begs to differ. Other sources which mentioned the inauguration merely stated that the Oranienbaum-Kronshtadt ice railway was the first in the Russian Empire.

This being said (typed?), the Russian ice railway was a far more impressive piece of engineering that the one in Québec. Yea, it was. Approximately 22.5 kilometres (14 miles) long, it could allegedly accommodate trains carrying up to 500 metric tonnes (500 Imperial tone / 550 American tons) of freight, but I digress.

In spite of the major accident mentioned above, the people behind the Saint Lawrence ice railway, or least some / many of them, would not give up. The weather was unseasonably mild in Montréal, however, in late 1881. As a result, construction of the track began only in late January 1882. Given the number of railroad cars awaiting at Hochelaga, speed was most certainly of the essence.

To make things worse, the ice broke in two places, creating gaping holes several metres (yards) wide. Given the problems associated with moving the track to a safer location, and the risk the ice might break up there too, the workers could only close up the holes. There was increasing concern that the poor quality of the ice might prevent the operation of the ice railway in 1882.

In any event, the first crossing was made a few days before the middle of February. On that same day, shortly after leaving Longueuil, the engineer of a train was horrified to see the ice sink, then crack under its weight. He gunned the engine of the locomotive and hoped for the best. The ice soon broke into several large blocks. The burst in speed might well have been the only thing which prevented the train from going under. Instead, it reached a part of the track where the ice was thicker. Traffic between the two shores of the Saint Lawrence River immediately came to a stop.

Two days later, workers cautiously went on the ice to examine the track. They discovered that the broken area had frozen solid. The track only needed minor repairs. Trains began to travel across it that same day. Their crews might not have been overly thrilled by the decision of their superiors.

Later that same day, as a train going to Longueuil reached the mid point of the ice railway, a locomotive and two of the three railroad cars jumped the track. That time around, the ice held. Workers soon rushed to the scene. The locomotive and the railroad cars were soon replaced on the track.

Regular traffic seemingly did not resume immediately, however, as some hitches, possibly sizeable snow drifts, continued to plague the ice railway until the second week of February. A rise in temperatures only made things worse. As operations slowly returned to normal, the workers kept a close eye on extensive openings in the ice present between Longueuil and Saint Helen’s Island.

Several days into the second half a February, as a locomotive stood idle in Longueuil, a fireman turned on the steam for some reason or other. The locomotive soon began to move toward some railroad cars on the track. Unable to stop it because he did not know how, the fireman became very, very nervous. Luckily, the conductor was able to jump aboard the locomotive and stop it before a collision could occur.

By early March, the locomotive towed only one railroad car at a time. Taking a heavier load seemed far too risky. Indeed, horses might have been put in service to further reduce the load on the ice. In any event, all traffic was stopped several days before mid March. The track was soon dismantled and stored. All in all, the ice railway had been operational for a measly 4 weeks in 1882, and…

You have a question, my reading friend? What did the trains which availed themselves of the service offered by the ice railway carry from Hochelaga to Longueuil, you ask? A good question. As you may well imagine, the loads varied from day to day, week to week, etc. This being said (typed?), one can state with a good degree of certainty that a lot of hay, real hay, not money of course, was carried in 1882. The previous year, potatoes had been carried in large quantities. In 1883, the main item of trade was lumber, but back to our story.

As could be imagined, the ice railway’s difficulties did not go unnoticed in Québec. Yes, the city, not the province. The government of Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, it seemed, had had enough.

In February 1882, the aforementioned Senécal sold the western (Montréal-Ottawa) half of QMO&OR to a Canadian transport giant mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since April 2018, Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CPR) of Montréal. He allegedly pocketed a personal profit of $ 100 000, or about $ 2 800 000 in 2023 currency. Would Senécal not be in a situation of conflict of interest, you ask, my reading friend? That was quite possible, if not probable, but do not forget that Senécal and Premier Chapleau were good buddies.

As general superintendent of QMO&OR, which meant that he was a provincial government employee, Senécal was also heavily involved in the sale of the eastern (Montréal-Québec) half of that firm to North Shore Railway Company of Montréal (?). Interestingly / shockingly, he was also a behind the scene member of the financial syndicate behind that purchase. Senécal’s participation became public in March, however, a revelation which caused quite a furore in the Assemblée législative du Québec. The official opposition was outraged, which was to be expected, but some / many members of Chapleau’s caucus were not too happy either. That unhappiness seemingly did not burst into the open, however. As a result, the controversial transaction was approved. Let us not forget that Senécal and Chapleau were good buddies.

Another nail in the sleepers / ties of the ice railway was driven home in early April 1882 when a newly created firm, Montreal & Sorel Railway Company of Montréal, began to run trains from Saint-Lambert, Québec, near Longueuil, to Sorel, via the Great Victoria Bridge. South Eastern Railway might, I repeat might, have made a deal with that firm at some point, so that it too could use the bridge. Worse was to come, however.

In December 1882, North Shore Railway sold the eastern half of QMO&OR to GTR and Senécal made more moolah. And yes, he made yet more moolah when the GTR sold that same eastern half of QMO&OR to the CPR, in 1885, but back to our story.

As you may well imagine, the sale of both halves of QMO&OR changed the way the ice railway operated during the winter of 1882-83 season. North Shore Railway had no need of it because its friendly relationship with GTR meant that its trains could use the Great Victoria Bridge with no trouble at all. CPR, in turn, only needed the ice railway to carry some of the material and equipment needed to construct its then rapidly advancing transcontinental railway. This pretty much left South Eastern Railway as the sole serious user of the ice railway.

As luck would have it, Mother Nature seemed to have smiled a bit on South Eastern Railway during the winter of 1882-83. Construction of the ice railway began during the second week of January. The first trains left Hochelaga shortly after mid month. This being said (typed?), the traffic on the track showed a decline of 50 % as compared with 1882.

An occasion to boost the profile of the ice railway came in late January when Montréal hosted the first of a quintet of winter carnivals centered upon sports activities (hockey, skating, snowshoeing, tobogganing, etc.). Indeed, news reports published at least as far away as Selma, Alabama, stated that said railway would be a great attraction. Special excursion trains seemingly ran every hour at least at certain times between Hochelaga and Longueuil, and back. From the looks of it, they proved very popular with tourists and, probably, local residents as well.

Slightly before mid March, a heavy snow storm brought operations to a close until the track could be cleared – by men with shovels. Another snow storm hit a week later, which meant still more shovelling. Shovelling, you ask, my perplexed reading friend? Was that all that could be done in 1883? Well, it was. You see, unlike its land based rivals, the ice railway could not be cleared by rail-based snow ploughs. Well, it might perhaps have been possible to use snow ploughs but would you have dared to put one of these numerically challenged, expensive and heavy vehicles on the ice of the Saint Lawrence River?

Regular operations continued until early April when a great thaw came upon the Montréal region. An order came from above to dismantle the track. That order came in the nick of time. You see, the crew of the last train was lucky not to go through the ice. All in all, the ice railway had been in place but not necessarily operational during about 11 weeks in 1883, for a grand total of about 8 months of presence on the ice between 1880 and 1883.

As effective as it had been since 1880, the sad truth was that the ice railway remained as always at the mercy of the weather.

Worse was to come however. You see, my reading friend, South Eastern Railway was, if yours truly may use the name of one of his favourite rock bands, in dire straits. (Mark Freuder Knopfler rocks!) The situation had reached such a critical state that, in early October 1883, its directors transferred it into the hands of the holders of the firms which held the railway’s bonds. Given that the majority of said bonds were held by CPR, the action taken by South Eastern Railway’s directors turned that giant into the de facto owner of the railway.

In September 1887, the operations of South Eastern Railway were assumed by CPR.

By then, that firm could cross the Saint Lawrence River as it pleased. You see, trains began to cross the CPR’s railway bridge between Kahnawake, a First Nation community, a Kanien’kehá:ka community to be more precise, on the south shore of the river, and Lachine, Québec, on the island of Montréal, in late July 1887.

The aforementioned Senécal died in October 1887, at the age of 58, nine or so months after realising his long time ambition of joining the Senate of Canada. The passing of that unscrupulous speculator or brilliant entrepreneur, your choice, arguably permanently closed the book on the saga of the ice bridge railway between Hochelaga and Longueuil.

Incidentally, the sidewheel railway ferry steamer SS South Eastern which had complemented said railway was sold to Richelieu & Ontario Navigation Company Limited of Montréal, a company owned / controlled by, you guessed it, Senécal, until his death that is.

Having no need to carry railroad cars, that firm removed the tracks aboard the ship. SS South Eastern was used as a ferry between Longueuil, Saint Helen’s Island and Montréal until 1890, when it was sold to Canadian Pacific Car & Passenger Transfer Company of Prescott, Ontario, a firm which should not be confused with CPR. The ship seemingly remained in service until the late 1890s.

And thus ends our journey on the railway track of time. Please accept my apologies for the length of this text. My attempts to be brief are not yet fully successful. See ya later and…

What the heck, yours truly simply cannot let a cute little story go by without inserting it at this final station of our article on the ice railway. You may remember that, in March, I readily admitted that I have had, have and will presumably continue to have a strong affinity toward the unusual, the strange, the odd looking, etc. Well, here is confirmation of that flaw in my genetic makeup.

In mid October 1882, the proprietor of the Club House Hotel of Longueuil, a gentleman by the name of McGuire, was at the Longueuil wharf on business when he spotted, “basking below the surface, apparently asleep, a huge and hideous monster.” Before long, an agent of the South Eastern Railway by the name of Twohey, the captain of the sidewheel railway ferry steamer SS South Eastern as well as some villagers were attracted to the spot and saw what appeared to be a huge snake with a dark mottled back and whitish belly. Judging from the many coils of the beast, the witnesses thought it had to be at least 12 or so metre (40 or so feet) long.

Even though several modes of attack were proposed to deal with the giant water snake, none of the witnesses volunteered to lead the charge. As a few hours passed, the beast remained where it was, harming no one and being harmed by no one. At some point, however, the water snake silently and stealthily slithered away.

Incidentally, there were / are honest to goodness water snakes in Québec. Indeed, the common water snake was / is quite common in that province. The largest individual ever spotted / captured was a female approximately 1.5 metre (approximately 5 feet) long. Getting on the nerves of a snake of that size at close range might not be a good idea, my reading friend. A bite would be very painful. Members of that thoroughly harmless species of ophidian are usually a lot smaller, however, having an average length of 70 to 80 or so centimetres (27.5 to 31.5 or so inches). Even so, the bite of a snake of that size defending itself from a pesky human might not be soon forgotten, but I digress.

And yes, I have been bitten, once, by a small bull-snake, I think, a good 40 years ago, when I had hair. (Sigh…) It actually drew blood, a small drop or two. Prying the jaws of that ophidian off my finger without injuring it proved a tad complicated. Still, I bear no ill will toward that snake. It had not gone out of its way to capture me, quite the opposite. I got what I deserved, but back to our cryptid story, a cryptid being an animal whose existence is not recognised by the scientific community, for very good reasons: by and large, these animals, be they lake creatures or large hominids, simply do not exist, but I digress. Again.

As long as we are at it… And you, my outraged reading friend, have a question. How about the giant squid? Is this not a cryptid which proved to be real? Well, at the risk of stirring a hornet’s nest, one could argue that it was never really a cryptid. You see, 60 or so reports concerning closely seen / examined specimens of such beasties were / are known to exist for the years prior to 1882. The oldest one dated / dates from 1546. How many other specimens were seen / examined just as closely but never reported will never be known of course. The total number of lake creatures, large hominids or tooth fairies examined in similar detail was / is… zero, and back to our story.

As long as we are at it, and if you do not mind a further digression, there once was at least one snake whose girth rivalled that of the Longueuil water snake. I kid you not. Titanoboa lived 58 to 60 million years ago in what is now Colombia. Comparing the fossils unearthed with bones of similar snakes alive today (python, boa and anaconda for example) led paleontologists to state that this ophidian could reach length of up to 13 or so metres (43 or so feet). It might have weighed close to 1 150 kilogrammes (close to 2 550 pounds). Ouch!

And yes, there have been claims that snakes as big as Titanoboa, if not bigger, still live in South America, in the Amazon river basin. End of the second digression. Sorry and… pleasant dreams.

By evening, the whole of Longueuil was abuzz with news concerning the sighting of the giant water snake.

Would you believe that a barrister / advocate by the name of Charles L. Gethings reported that, a few days before, while out on the Saint Lawrence River with a few ladies, a huge something emerged from the water as the sky turned dark, when night fell? Worse still, that something pursued the small party over a considerable distance. The ladies were understandably much alarmed, stated Gethings. Personally, I have a feeling that he was just as alarmed as his companions, but I digress.

The day after McGuire’s extraordinary sighting, a sizeable percentage of the male population of Longueuil was out in boats carrying all sorts of more or less useful contraptions destined to capture the giant water snake and / or kill it so that its carcass could be displayed in the halls of a recently inaugurated (August 1882?) museal institution located on the site of what was then McGill College and colloquially known as the Peter Redpath Museum.

You do remember the similar scene in the 1975 (!) blockbuster thriller motion picture Jaws, do you not? Male Homo sapiens can be stupendously dumb at times. I mean, going after a 12 or so metre (40 or so feet) long snake in rowboats? Come on…

According to the news report yours truly came across, the shenanigans taking place near Longueuil proved irresistible to a reporter of a Montréal daily, The Montreal Daily Star, or to its publisher, Hugh Graham. Mind you, it is also possible that some of the witnesses had a bit of fun at the expense of said reporter, who published an article yours truly was tickled pink to paraphrase in the preceding paragraphs.

The Montreal Daily Star seemingly did not, however, publish an article on the reception its reporter got when he went to see the captain of SS South Eastern to get some information. You see, my reading friend, the good captain laughed. There was no snake, he stated, only a piece of rock. He then took the reporter to the site of the sighting to prove his point. There, said reporter saw a large flat piece of rock which broke the surface of the water more or less frequently at one end.

Ta ta for now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)