Hauling freight on thin ice: The ice bridge railway between Longueuil, Québec, and Hochelaga / Montréal, Québec, Part 1

While yours truly cannot claim to be a well-known ferroequinologist or a model train aficionado like the theoretical physicist Sheldon Lee Cooper, I do like train travel. A passenger train will beat an intercity bus any day. And do not get me started on air travel. Please. I mean, what is there to like about air travel? All of this to say (type?), that I would like to bring to your attention a most interesting aspect of the history of railways in Canada. Are you ready? All aboard, and no, change is never fine. (Hello, EP!)

Once upon a time, in the second half of the 1870s to be more precise, there was a railway, more specifically South Eastern Railway Company of Montréal, Canada, a relatively small firm founded in 1866 by American interests, in what was then the Province of Canada, as South Eastern Counties Junction Railway Company, but renamed in 1872 as a result of its merger with Richelieu, Drummond and Arthabaska Counties Railway Company of Montréal (?).

Thanks to its connections with an American railway firm, Connecticut and Passumpsic Rivers Railroad Company, South Eastern Railway hoped to create a link between Montréal, Québec, the metropolis of Canada, the country of course, founded in July 1867, and Boston, Massachusetts, I think. Said link would compete with the ones already operated by two heavy hitters which were on rather friendly terms, an American one, Central Vermont Railway Company, and a Canadian one, Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada (GTR), of Montréal.

The latter’s displeasure with the South Eastern Railway project turned into outright hostility when, in 1879, I believe, that firm acquired (leased?) a railway line operated by the Montreal, Portland and Boston Railway Company of Montréal. You see, said line, which went from Farnham, Québec, to Longueuil, Québec, on the South shore of the Saint Lawrence River, within sight of Montréal, was an ideal complement to the South Eastern Railway line which went from Farnham to Newport, Vermont. South Eastern Railway, it seemed, was on the verge to achieve its goal, the aforementioned link between Boston and Montréal.

As was to be expected, South Eastern Railway soon asked GTR how much it would have to pay to put its trains on the Great Victoria Bridge, the only railway bridge which spanned the mighty Saint Lawrence River. GTR, a firm founded in good part with English moolah and run by Québec / Canadian businessmen who seemingly did not know the meaning of the word mercy, would have none of it. South Eastern Railway trains found themselves subjected to long and, in the firm’s eyes, utterly unnecessary and unacceptable delays. As well, negotiations between the two railway firms over the running rights for the Great Victoria Bridge became so acrimonious that South Eastern Railway simply walked away.

It so happened that, as that firm remained intent on finding a way to reach Montréal from a station on the South shore of the Saint Lawrence River, another railway firm, that one with access to a train station in Montréal, was intent on reaching the South shore of the Saint Lawrence River and points beyond. That railway firm was Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway Company (QMO&OR) of Montréal (?).

QMO&OR had come into existence in 1875 as a result of the failures of Quebec North Shore Railway Company of Québec, Québec, and Montreal, Ottawa & Western Railway Company of Montréal (?), failures caused by a lack of federal financial assistance and a lack of British financial involvement, failures which might, I repeat might, have been caused by behind the scene lobbying on the part of GTR. And no, the governments which held power in Québec and Ottawa, Ontario, were not of the same political persuasion.

Incidentally, Montreal, Ottawa & Western Railway was initially (1869) known as Montreal Northern Colonization Railway Company. The Chemin de fer du Nord, in English the railway of the North, as it was commonly called, owed its existence in a large part to the efforts of a giant of late 19th century Québec, François Xavier Antoine Labelle, a Roman Catholic priest also known as the Roi du Nord, in English the King of the North, who played a crucial role in the colonisation / occupation of the Laurentian region of Québec, on the North shore of the Saint Lawrence River, but back to our story.

Unwilling to see Quebec North Shore Railway and Montreal, Ottawa & Western Railway go under because of their potential importance in the development of Québec, the provincial government headed by Charles Eugène Napoléon Boucher de Boucherville, a physician, took them over and formed QMO&OR.

When that action occurred, however, Québec and much of the world were in the throes of the depression of 1873-79, or great depression of 1873-1896, depending on the metrics used to evaluate that somber period. To make things worse, behind the scene lobbying on the part of GTR meant that investors, both in North America and overseas, chose not to invest in QMO&OR, which forced Boucher de Boucherville to invest public money in that costly venture.

By late 1877, the provincial deficit was such that Boucher de Boucherville had to resort to a desperate measure. No longer able to borrow on the open market, the government passed a law, in January 1878, which forced the towns and cities along the railway lines serviced by QMO&OR to cough up the moolah they had promised, but never delivered, in order to enjoy this privilege. The local authorities in those cities and towns were not amused.

The ensuing uproar gave the Lieutenant Governor of Québec, Luc Horatio Letellier de Saint-Just, an excuse, an excuse he had long been waiting for actually, to dismiss Boucher de Boucherville, in March, even though his party held a majority in the Assemblée législative du Québec and the Conseil législatif du Québec, in a way the senate of the province. Better yet, or worse still, your choice, he entrusted the leader of the official opposition, the Franco Quebecker Henry Gustave Joly, with the task of forming a new government.

Did I mention that Joly and Letellier de Saint-Just were of the same political persuasion?

Members of Boucher de Boucherville’s party accused Letellier de Saint-Just of masterminding a coup d’état, which might not have been too far from the truth. Indeed, both the Assemblée législative du Québec and the Conseil législatif du Québec passed motions of censure against him. The unelected Letellier de Saint-Just regally ignored them.

Even members of the federal counterpart of Joly’s political party, up to and including Canada’s Prime Minister, Scottish Canadian Alexander Mackenzie, were shocked, and embarrassed, by the action of Letellier de Saint-Just, an individual they had appointed. That action, which caused a political and constitutional crisis in Québec, was well and truly condemned by Mackenzie and company, but only in private.

As it turned out, Joly and his party won 31 seats in the ensuing general election, held in May 1878. Boucher de Boucherville’s party won 32 seats – and lost the election. Yes, yes, it lost the election. You see, my outraged reading friend, the two independent members of the Assemblée législative du Québec chose to support Joly, and this even though their political persuasion was nearly identical to that of Boucher de Boucherville.

Members of the latter’s own caucus added insult to injury by preferring someone else to lead them. That someone was a lawyer named Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau. Bowing to the inevitable, Boucher de Boucherville resigned as leader of his political party, but back to the story at the heart of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Its irresistible will to cross the Saint Lawrence River having met an immovable object, namely GTR, South Eastern Railway representatives came to an agreement with QMO&OR representatives at some point in the late 1870s, quite possibly in 1879 or perhaps as early as 1878.

No later than January 1880, a group of francophone and anglophone Québec businessmen got ready to launch a firm with an unusual name and an even more unusual goal, namely Railway Crossing Company between Hochelaga and Longueuil. You see, said firm intended to lease, buy or build one of more ferries which would carry railcars or entire trains across the Saint Lawrence River. Mind you, it also intended to build a rail track on the ice which covered that river in wintertime, thus linking the South shore of that mighty waterway to the island of Montréal. I kid you not.

Whether or not the firm under discussion was actually created was / is unclear, however. Said creation was still being discussed in April 1880, when its name was mentioned in Gazette Officielle de Québec for the last time.

Ice bridges between Longueuil, on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, and Hochelaga, on the island of Montreal, were nothing new. People on board horse-drawn sleighs made the trip no later than the 1830s, and…

Have no fear, my skittish reading friend. The thickness of the ice between Hochelaga and Longueuil consistently exceeded 60 centimetres (2 feet) in the 1870s and 1880s. That much good quality ice could support a load of 22.7 metric tonnes (22.3 Imperial tons / 25 American tons). In some areas, the ice could be 1.2 metre (4 feet) thick. It would support a load well in excess of 100 metric tonnes (100 or so Imperial tons / 110 American tons). The catch was that the current delayed freezing until temperatures really dropped. By then, pieces of ice had run into the ice already present. As a result, numerous growlers, in French, bourguignons, were to be found between Hochelaga and Longueuil.

And yes, bourguignon is a fun word, a bit like the French word abat-jour – or the German word flugzeug. (Hello, EP!)

Louis Adélard Senécal. L’annaliste, “Les hommes du passé – Louis Adélard Senécal.” Le Monde illustré - Album Universel, 3 May 1902, 5.

Construction of the ice railway between Hochelaga and Longueil began in January 1880, almost in mid month perhaps, under the supervision of the general superintendent of QMO&OR. According to some, Louis Adélard Senécal, one of the most formidable, imaginative and successful francophone Canadian businessmen of the age, was the one who had put forward the idea of an ice railway.

Indeed, would you believe that this cunning individual owed his QMO&OR position to his good buddy Chapleau, the Premier of Québec since the fall of Joly’s minority government, in October 1879, as a result of a non confidence vote? Indeed, again, for some years, he had been the treasurer of the party then led by Chapleau. And yes, Senécal was also a good buddy of Boucher de Boucherville.

Would you believe that that Senécal had played a behind the scene role in the fall of said Joly government? That well connected operator had also played a role in the destitution of the aforementioned Letellier de Saint-Just, in July 1879, a destitution facilitated by the fact that the aforementioned Mackenzie and his political party had lost their grip on federal power as a result of the September 1878 general election. Given all that, Chapleau owed Senécal big time, which explained the QMO&OR position, and other things we do not have the time to dwell into. Well, maybe a little.

Was QMO&OR a nest of patronage and corruption which funnelled moolah into the coffers of the political party led by Chapleau, you ask, my concerned reading friend? Is the pope, Franciscus / Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Argentinian? But I digress.

Construction of the ice railway, state I, began in mid January 1880. Many workers began by levelling the ice over a width of 20 or so metres (65 or so feet). Checking the thickness of the ice every few metres (yards), they laid wooden beams every 2.15 or so metres (7 or so feet), to reduce the vibrations transmitted to that ice. The workers then put long planks on top of the beams. Every 90 or so centimetres (3 or so feet), they placed sleepers / ties on the planks. Lightweight rails were then put on top of everything. To reinforce the track, the workers pumped water between the planks and beams, where it soon froze.

By the time the rail track was completed, in late January, it was 2 800 or so metres (9 100 or so feet) long, I think. A short part of the track was over the shore of the river at Longueuil while a much longer part was over the docks in the port of Montréal, and led to the train station in Hochelaga.

From the looks of it, the track was tested at least once by running horse drawn railcars between Longueuil and Hochelaga. A locomotive also ventured in the ice over a (short?) distance.

In any event, the official opening of the ice railway took place on 30 January 1880. Chapleau, Senécal and a lot of bigwigs were there, as was to be expected, as were hundreds of cautious well wishers assembled on both sides of the river.

And yes, there was some final tweaking due to the fact that raising temperatures had caused some melting of the ice. A relatively small portion of the track had also gone down a tad. You see, two heavily loaded railcars had been left there for a couple of days. Oops…

On 30 January 1880, a small and relatively light locomotive, the gaily decorated (flags, evergreen branches, banners and a single stuffed beaver) W.H. Pangman, owned by Laurentian Railway Company of Montréal (?) but leased by South Eastern Railway, left the Hochelaga station of QMO&OR, on the island of Montréal. It was pulling a tender, of course, and 2 flatcars fitted with temporary seats on which 100 or so very important passengers (VIPs) sat. And yes, Chapleau, Senécal and a lot of bigwigs were there, including the president of Laurentian Railway, John Henry Pangman.

Dozens and dozens of horse driven sleighs accompanied the train, some of them possibly from a safe distance. Even so, some of the horses took fright and proved difficult to calm down. Mind you, the explosion of 3 or 4 fog signals laid by the track probably did not help.

By the way, the Vice-President of Laurentian Railway, Hilaire Hurteau, was a Member of Parliament on the government side and a great nephew of the late Isidore Hurteau, the step father of Clément Arthur Dansereau, a powerful fixer and owner of the pro-government (provincial and federal) daily newspaper La Minerve of Montréal, who was also Chapleau’s grey eminence. Incidentally, Dansereau was related to Senécal by marriage, the latter’s spouse being Justine Delphine Senécal, born Dansereau, a cousin or niece of his, I think, but I digress. And yes, small world…

According to many contemporary and present observers, Chapleau, Dansereau and Senécal formed a triumvirate, a state within the state, an unholy trinity dare one state, which ran the province of Québec as its private plaything, but back to our train of thought.

As the train travelled east, on the ice, on its way to Longueuil and the station of South Eastern Railway, the VIPs felt neither jolting nor unpleasant sensations. This being said (typed?), as the train moved forward, compressing the ice, seeing water spurting out of holes previously drilled into that ice to measure its thickness proved a tad unnerving.

As it neared the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, the train made a 10 or so minute stop to allow a pair of well known Montréal photographers who might not have been on board, namely Henry “Hy” Sandham of the famous Notman & Sandham photography studio as well as Alexander Henderson, to immortalise the moment. Some VIPs could not repress a giggle or three when the train restarted. You see, Sandham began to run after said train, frantically waiving his arms. He had just missed a good shot. The train did not stop. One does not stop progress, especially when there is moolah to be made.

The train thus made its way to the South Eastern Railway shed in Longueuil. Its passengers then disembarked and walked to a building where refreshments and plenty of food were served. The local Member of Parliament, a government back bencher by the name of Charles-Joseph Coursol, presided the celebrations, quite possibly at the request of Bradley Barlow, chairperson of South Eastern Railway and member of the United States House of Representatives. And yes, there were moult toasts and speeches, most of these in French. An emotional Senécal allegedly shed some tears.

The train and, it seemed, 200 or so VIPs returned to Hochelaga / Montréal later in the day.

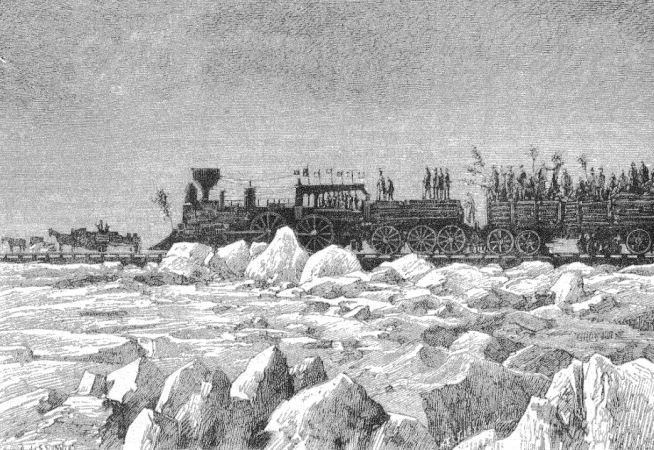

And here a series if drawings made to illustrate various aspects of the activities of 30 January 1880…

Various aspects of the activities surrounding the launch of the ice railway between Longueuil, Québec, and Hochelaga, Québec. Anon., “Montreal – Incidents at the opening of the ice railway bridge.” Canadian illustrated News, 14 February 1880, 105.

As one might expect, many (every??) newspapers in Montréal dealt with the launch of the ice railway. La Minerve almost waxed lyrical about the exploit of Senécal and his associates. La Patrie, a newspaper which was not pro-government, on the other hand, was slightly more sarcastic. It especially went after Étienne Théodore Pâquet, a member of the quintet of Assemblée législative du Québec members who had crossed the floor, in October 1879, during the political crisis which had led to the aforementioned fall of the Joly government. Pâquet, according to La Patrie, was a sellout and turncoat. In October 1879, it had referred to him as a traitor.

The truth was that this treachery proved quite advantageous to Pâquet, whose position went from that of backbencher, in other words a nobody, in the government of Joly to that of Secrétaire provincial du Québec, the equivalent of a minister of the interior, in the government of Chapleau.

By the way, the Lieutenant Governor who chose to entrust the leader of the official opposition, in other words Chapleau, with the task of forming a new government was of the same political persuasion as said Chapleau. His name was Théodore Robitaille.

And yes, my reading friend, the unveiling of the ice railway was mentioned in a number of foreign (American, British, French, etc.?) publications, including the prestigious American weekly magazine Scientific American (1881) and the equally prestigious French weekly magazines La Nature (1883) and Le Génie civil (1883). The French language articles even included an engraving, the same one actually. And yes, that engraving was based on a photograph taken by the aforementioned Sandham, but I digress.

Incidentally, as prestigious as it was, La Nature had some gaps in its knowledge of North American geography. The ice railway was most certainly not located in the United States.

As the risk of sounding flippant, yours truly came across another railway related oopsy perpetrated this time by a prestigious and very interesting French quarterly magazine, namely Tintin c’est l’aventure. On the cover of its December 2022-February 2023 issue, one can see a gorgeous photograph of a Canadian Pacific Railway Limited freight train passing through Banff National Park, in Alberta, in January 2019. A closer look at said photograph shows that the words Canadian Pacific on the locomotive are reversed. Yes, yes, reversed, but back to our story.

As gratifying as the results of the inaugural trip of the ice railway were, and as useful as the winter rail link was, there were many among the Montréal elite who had more or less serious misgivings. If temperatures were to rise, the integrity of that railway could be compromised, with potentially fatal results.

And that dramatic thought might be a propitious moment to sagely derail this train of thought. Please come back next week to see how things developed.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)