A brief portrait of a dynamic duo of dentists from Québec, Québec, Henri Edmond Casgrain and Marie Wilhelmine Emma Casgrain, born Gaudreau, during the Belle Époque – and a little something on their first horseless carriage, a Bollée Voiturette, part 3

Hello, my assiduous reading friend. As promised, here is the 3rd and final part of this article, a part during which yours truly will conclude the fascinating story of the Bollée Voiturette designed by the French automobile pioneer Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée.

The first competition in which said Voiturette, a quartet of Voiturettes in fact, seemed to participate was the Course de voitures automobiles Paris-Marseille-Paris which was held in France, obviously, in September and October 1896. The distance to be covered being 1 710 or so kilometres (1 060 or so miles), it certainly could not be covered in a single day.

At most, around 15 or so of the 30 or so participants crossed the finish line, including only 1 of the 4 Voiturettes, which actually finished in last place. That vehicle was obviously the one you have just been ogling.

One wonders whether a sporting event as long and arduous as the Course de voitures automobiles Paris-Marseille-Paris did not exceed the adaptation capabilities of a light vehicle like the Voiturette. Mind you, their drivers also had bad luck.

At the time that competition took place, British motorists were certainly not as free in their movements. Indeed, they still lived under the yoke of the Locomotives (Amendment) Act 1878. Yes, yes, the act mentioned in the 2nd part of this article.

British motorists, who, let us not forget, were people with money and high social status, were outraged by those constraints. They demanded that the Locomotives (Amendment) Act 1878 be amended or repealed.

In August 1896, the Locomotives on Highways Act 1896 received royal assent, making it an official legislative measure which eliminated the presence of the pedestrian and increased the maximum permitted speed of “light locomotives” to 22.5 or so kilometres/hour (14 miles/hour) in the countryside. Mind you, those vehicles had to carry a bell or some sort of noisemaker to give warning of their approach.

And yes, several local authorities took advantage of a clause in the law to reduce a tad the maximum speed in the countryside.

The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896, the Magna Carta of motor cars according to many, came into force on 14 November 1896. England’s Motor Car Club and the co-founder and chairman of British Motor Syndicate Limited, Henry John “Harry” Lawson, a founding member of said club, chose that historic day as the date of a procession / stroll of 85 or so kilometres (a little less than 55 miles), on English soil obviously, more specifically between London and Brighton, a very popular seaside resort.

As the days went by, firms and individuals registered nearly 55 participating vehicles, which did not necessarily mean that everyone was at the starting line on 14 November.

As luck would have it, motorists taking part in that procession had to face a situation which was deplorable to say the least: it had rained almost all night and the roads were soaked.

Come to think of it, the use of the term procession might not have been appropriate. Indeed, some of the 30 or so drivers present, including possibly Voiturette drivers, started to put the pedal to the metal in order to arrive in Brighton before everyone else. Worse still, at least one of the Voiturette drivers might, I repeat might, have skipped the mandatory lunch break and one of the required stops to race ahead.

Along the way, Bollée unfortunately frightened a horse which immediately knocked down a lady. For some reason he did not stop. I know, I know, that lack of consideration was rather disturbing, especially since Bollée was not taking part in a race. Let us be charitable and suggest that he did not see the accident he had just caused. In any event, the report prepared by a police officer only mentioned for identification the fact that the offending motorist was at the head of the pack.

Who won that race which was not one? Bollée, of course, with one of his racing automobiles. Better yet, his younger brother, Camille Amédée Alfred Bollée, came in 2nd place, also at the controls of a Voiturette. That was very good news.

What was much less fun was the arrival, several / many days later, of a formal notice indicating that Bollée, yes, Léon Bollée, had a large fine to pay, following the accident he had caused.

By the way, only 15 or so vehicles appeared to arrive in Brighton.

A good sport, Bollée was about to send a check when he heard about another participant in the procession, Edward Joel Pennington, a grandiloquent American inventor with swindling tendencies who had sold patents to Lawson a few months before.

Bollée was stunned to learn that Pennington claimed to have arrived in Brighton first at the controls of an example, perhaps the first one, of his gasoline tricycle, the Pennington Autocar, which was a blatant lie, said vehicle having arrived in 8th place.

A brilliant and delicious idea popped up in Bollée’s mind, however. He sent Pennington a note which read as follows, it was said, once translated: “Since you claim to be the first to arrive, I imagine that the summons sent to me concerns you… and also the conviction. Please be kind enough to pay the amount of the fine.” Not wishing to be seen as a liar, Pennington was said to have paid the fine, as he cursed Bollée to high heaven.

At the end of December 1896, Bollée challenged Pennington to travel the roads linking London and Brighton a second time aboard the vehicles used in November. He even stated he was ready to participate with him in the Marseille-Nice race which was to take place in France in January 1897. You see, Pennington had the nerve to question the performance of the Voiturette.

Pennington refused to be pushed around, however. In fact, that braggard doubled down through several letters published in early 1897 issues of the English weekly magazine The Autocar. In the end, he preferred not to race with Bollée, a position which attracted much ridicule.

A member of the senior management of Coventry Motor Company, a firm which produced the Voiturette under license in England, was particularly scathing. Herbert Osbaldeston Duncan seemed unable to stomach the fact that Pennington had (correctly?) claimed to have won over him twice during tugs of war, in Coventry, involving an Autocar and a Coventry Motette, the English-made version of the Voiturette.

Another American was far more displeased than Pennington at the end of 1896, but for very different reasons. You see, the American inventor / mechanic and automobile pioneer James Frank Duryea claimed to have arrived in Brighton before anyone else in a vehicle manufactured by the American firm Duryea Motor Wagon Company. For some reason or other, Duryea’s automobile might, I repeat might, have been locked away in a shed, out of sight, shortly after his arrival in Brighton.

Some said that Duryea had joined the procession along the way or that he had not signed up to take part in it. Others, however, argued that Lawson and British Motor Syndicate wanted the Voiturette to hog the limelight, in order to boost sales of the Motette.

And yes, as far as many American newspapers were concerned, Duryea had won the London to Brighton race.

In any event, Duryea’s answer came very quickly. Outraged by what he judged to be an attempt to sweep his victory under the proverbial rug, Duryea refused to participate in the opulent banquet which honoured the participants. The absence of that American without support or ally in England bothered absolutely no one.

A single-seat racing Bollée Voiturette with 2 engines. Anon., “Voiturette Léon Bollée à une place – Type de course.” Les Sports modernes, June 1898, between pages 8 and 9.

As you might imagine, specially designed single-seat Voiturettes took part in many of the races held in the following months. Those vehicles were in all likelihood powered by 2 engines instead of just one.

Let us start by mentioning the first Coupe des motocycles which was held in France at the end of June 1897. The 20 or so participants had to make the round trip between Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Ecquevilly, not far from Paris, France, 5 times – a total distance of 100 or so kilometres (a little over 60 miles). Bollée came in first place.

Two other Voiturette drivers, a French aristocrat, Viscount Martial Jean Henri Raymond du Soulier, and a French cannery industrialist / racing driver, René Pellier, respectively came in 3rd and 4th place. The latter actually raced with a passenger in the front seat of his two-seat Voiturette.

The Course d’Automobiles between Paris and Dieppe, France, was held at the end of July 1897. Nearly 60 motorised vehicles of all types were on the starting line. A French industrialist and racing driver, Paul Jamin, triumphed at the controls of a Voiturette. Pellier came in second place at the controls of another Voiturette.

Paul Jamin and the Bollée Voiturette he drove to victory in the race between Paris, and Trouville-sur-Mer, France. Frantz Reichel, « Paris-Trouville. » Le Sport universel illustré, 28 August 1897, 447.

Around mid-August, Jamin came first again, this time in the race between Paris and Trouville-sur-Mer, France, on the shores of the Channel, and…

What is this stunned look that I see lighting up your face, my reading friend? Did you not know that colour photography processes existed in 1898?

This being said (typed?), yours truly finds it very difficult to tell you which photographic process was used to produce the original image, subsequently reproduced a great many times for insertion in the June 1898 issue of the French monthly Les sports modernes, thanks to a process of engraving and printing, chromotypogravure, I think, invented in France around 1845 by the French engraver Joseph Isnard Louis Desjardins, but back to our races, and…

All right, all right, keep your knickers on, my reading friend. The colour processes available in 1898 were apparently those recently developed by the American technician / inventor Frederic Eugene Ives, the Anglo Irish professor / physicist / inventor John Joly and the Franco-Luxembourgish physicist / inventor Jonas Ferdinand Gabriel Lippmann. Jeez, how cranky you are at times.

Viscount Martial Jean Henri Raymond du Soulier aboard his Bollée Voiturette racing automobile. Anon., “La Côte d’Azur sportive.” La Vie au Grand Air, 1 April 1898, 7.

At the beginning of March 1898, the Viscount du Soulier came in 1st place in his category during the Marseille-Nice race, a grueling competition which took place over 2 days on a course of 200 or so kilometres (125 or so miles), I think.

By the way, the high speed and elongated shape of the Voiturette, especially in its racing version, which sometimes had a pointed metal nose, meant that some people gave it the nickname “torpilleur de la route,” in English torpedo boat of the road.

As you are well aware, my reading friend with encyclopedic knowledge, a torpedo boat from the end of the 19th century was a small, fast and agile warship whose function was send to the bottom large warships of an opposing navy using torpedoes.

Mind you, the total lack of protection given to the person who sat in the front seat of a standard version Voiturette meant that this vehicle was sometimes given another nickname, the “tue belle-mère,” in English mother-in-law killer. I kid you not.

Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée and his Voiturette about 200 metres (about 650 feet) from the finish line of the second edition of the Critérium des Motocycles, Étampes, France. Frantz Reichel, “Le Critérium des Motocycles.” Le Sport universel illustré, 7 May 1898, 306.

Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée and his Voiturette shortly after crossing the finish line of the second edition of the Critérium des Motocycles, Étampes, France. Frantz Reichel, “Le Critérium des Motocycles.” Le Sport universel illustré, 7 May 1898, 307.

At the end of April 1898, during the second edition of the Critérium des Motocycles, Bollée completed the 100-kilometre (62 or so miles) round trip between the French cities of Chartres and Étampes in 1 hour 59 minutes, thus establishing a world speed record of 50.4 kilometres/hour (31.3 miles/hour). The very morning of the competition, Bollée had done even better, albeit in an informal setting: 25 kilometres in 25 minutes, which corresponded to an average, I repeat average, speed of 60 kilometres/hour (37.3 miles/hour). Sports commentators of the time were stunned.

Indeed, would you believe that 11 of the first 15 vehicles to cross the finish line of the second edition of the Critérium des Motocycles were Voiturettes? I kid you not.

The weight of Bollée’s Voiturette exceeding the maximum allowed for the competition, however, he was disqualified. Bollée accepted that decision with philosophy, especially since the new winner of the competition, a Portuguese employee of the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles, Wilfrid, whose real name was Alfredo Lavezze, also drove a Voiturette. And here he is…

The final winner of the second edition of the Critérium des Motocycles, Alfredo Lavezze, better known as Wilfrid. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Jules Beau, tome 6 (1898), image 614.

In early May, a trio of Voiturettes came in 1st, 2nd and 3rd in their category in the Course d’automobiles de Périgueux, an 85 or so kilometre (a little less than 55 miles) return trip between two French municipalities, Périgueux and Mussidan. The drivers of those vehicles were respectively Wilfrid, Count Félix de Fayolle de Tocane and Louis Didon. Wilfrid’s average speed over the first 35 kilometres (22 or so miles) of the course was a staggering 57.1 kilometres/hour (35.5 or so miles/hour) – a world speed record. Wah!

And yes, my reading friend with a memory like a steel trap, Didon was related to Marie Didon, born Boisseau, one of the first French female motorists and a lady mentioned in the 2nd part of this article. Indeed, he was her son.

Paul Jamin and his Bollée Voiturette at a hill climbing competition held in December 1898 near Chanteloup-les-Vignes, France, near Paris. He came in second. Anon., “Automobile – Une course de côte.” Le Sport universel illustré, 10 December 1898, 802.

In late July, yes, July 1898, Jamin won the Tours-Blois-Tours race, in France, at the controls of the Voiturette that Bollée had driven between Chartres and Étampes. Better yet, he beat Bollée’s record by covering the 100 kilometres (62 or so miles) of the race at an average speed of 53 kilometres/hour (32.9 miles/hour).

By Bollée’s own admission, his staff spent 8 of the 12 months of each year preparing for races. That considerable effort obviously reduced the number of vehicles sold to individuals or businesses.

In total, around 1 200 (?) Voiturettes manufactured by Diligeon & Compagnie and the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles, as well as by Coventry Motor and, it seemed, Humber & Company travelled on the roads of France, the United Kingdom and other countries, including Canada, from 1896 onward.

Before I forget, the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles manufactured a certain number of Voiturettes which had 2 seats in the front position, and this as early as 1897. And here is proof…

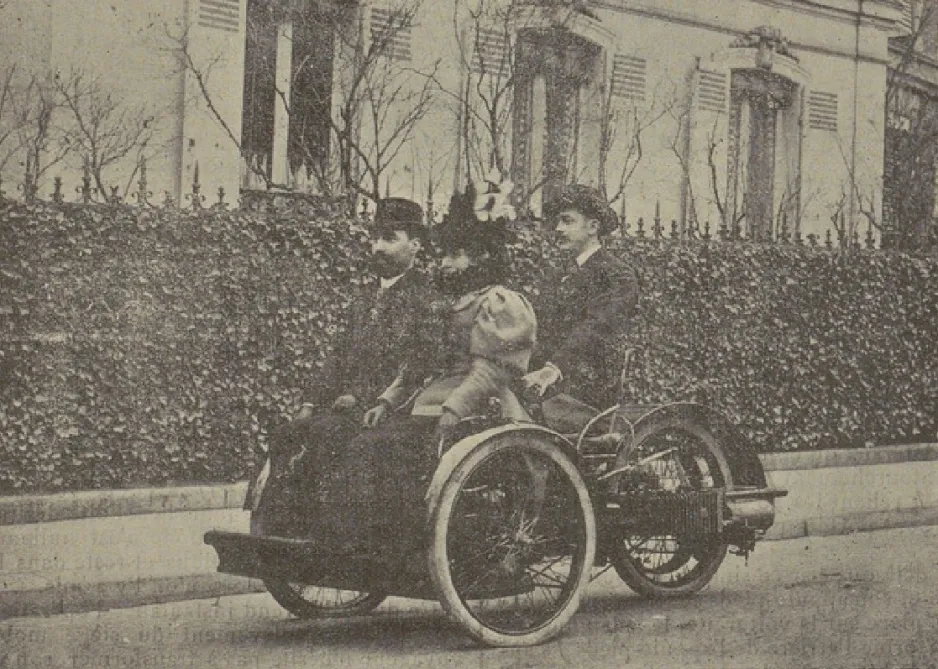

A typical Bollée Voiturette 3-seater. The gentleman in the front seat might be Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée. G. D., “Expositions du Cycle et de l’Automobile.” La Locomotion automobile, 30 December 1897, 615.

And yes, my somewhat elitist reading friend, the couple to which belonged such a 3-seater vehicle could be driven where it wanted to go by a servant. The motorised beau thus had all the time to whisper (howl?) sweet nothings in the ear of his belle, which was not really easy aboard a conventional Voiturette.

The prototype of the Bollée Voiturette with a folding hood and windshield. G. D., “Expositions du Cycle et de l’Automobile.” La Locomotion automobile, 30 December 1896, 617.

Mind you, the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles also introduced a single-seat version of the Voiturette with a hood and folding windshield in early 1898. That “victoriette,” a term which seemingly referred to a small automobile, was obviously far more comfortable than the basic model.

Speaking (typing?) of comfort, you will remember that, in its original version, the Voiturette was not equipped with shock absorbers. This was a somewhat painful deficiency that Bollée did not remedy until the spring of 1899, by installing a leaf spring suspension on the front wheels. Said suspension also considerably reduced the skidding tendencies of the rear drive wheel.

Before I forget, the firm introduced a two-seater Voiturette with a detachable front seat in 1897.

A photograph taken from an advertisement showing the detachable front seat of the Bollée Voiturette version introduced in 1897. Anon., “Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles.” Les Sports modernes, July 1898, unpaginated.

A typical Bollée Voiturette with a detachable front seat. Anon., “Voiturette Léon Bollée à deux places.” Les Sports modernes, June 1898, between pages 16 and 17.

It should be noted that the space between the front wheels of the Voiturette could be used for commercial purposes. That vehicle could in fact be used as a delivery vehicle, such as this one for example.

The Bollée Voiturette used by the linen store / hosiery Au Petit Paris of Bordeaux, France. Anon., “Nouvelle voiturette Bollée.” La Locomotion automobile, 17 February 1898, 110.

Would you also believe that the use of a Voiturette for purposes close to exploration was contemplated in 1899-1900? Here is proof…

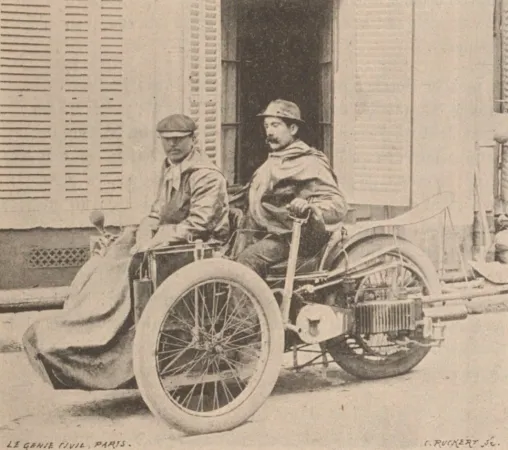

The Bollée Voiturette that the Frenchmen E. Janne de Lamarre, on the right, and his travel partner, Raphaël Merville, planned to use on Canadian soil, Paris, France. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Jules Beau, tome 10 (1899), image 217.

In February 1900, I think, a young French mining developer / editor / explorer / journalist, E. Janne de Lamarre, left Paris with his brother-in-law, Raphaël Merville, and a Voiturette. That dynamic duo, err, terrific trio embarked on a prodigious journey to Bennett, Yukon. To know more about that odyssey, you will have to wait, however.

And yes, my incredulous reading friend, the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles made at least one Voiturette fire truck. I kid you not. That to say the least very original vehicle carried a folding ladder and towed a small trailer.

A 4-wheeled version of the Voiturette, produced by the French firm Les Automobiles Darracq Société anonyme, I think, was not very successful. Yours truly wonders if the vehicle in question corresponded to the two-seater quadricycle that the Société anonyme des voiturettes automobiles had developed towards the end of 1899.

Incidentally, did you know that Les Automobiles Darracq, by then known as Alexandre Darracq Limited, produced the small engine that Alberto Santos-Dumont, a Brazilian aviation pioneer mentioned many times since November 2018 in our wonderful blog / bulletin / thingee, and others used around 1908 to propel early examples of his Santos-Dumont n° 20 Demoiselle?

As advanced as it was in 1896, the Voiturette was soon left aside by motorists looking for more comfort and space. Bollée himself moved on in 1903. The automobiles manufactured by his firm, the Établissements Léon Bollée, I think, were high-end vehicles. By acting in that way, Bollée unilaterally put an end to the agreement which had linked him to his older brother, Amédée Ernest Marie Bollée.

This being said (typed), almost 20 or so French and foreign automobile manufacturers, most of those British, seized or tried to seize the niche abandoned by Bollée, with more or less success.

And now is the time to introduce another aeronautical interlude into this discussion. After all, either one is a wing nut or one is not. And, just like Obelix, I fell into the cauldron when I was little.

Bollée became interested in aerostation no later than 1907, the year which saw the creation of the Aéro-Club de la Sarthe, an organisation that he himself chaired. The budding aeronaut even bought himself a gas balloon, which he (or his spouse?) christened Au Petit Bonheur.

Did you also know that Bollée played a significant role in the success of the visit to France of an American aviation pioneer mentioned many times in our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thingee since August 2018? A pioneer who flew with Bollée and 2 other people aboard said Au Petit Bonheur, in July 1908. Can you identify that prominent figure? Wilbur Wright, you say, my reading friend? Excellent answer. Fetch yourself a gold star, and… One, not two.

Wright had sailed for France in May 1908 to demonstrate the performance of the Wright Model A biplane. Once there, he joined American businessman / engineer Hart Ostheimer Berg, the representative of the Wright brothers in Europe, to find a place where he could assemble and test the aeroplane shipped to France in the summer of 1907.

Very intrigued by the Wright brothers, Bollée invited Berg and Wright to use a space in his factory, in the city of Le Mans, France. The two Americans readily accepted.

Léon Bollée, on the right, with Wilbur Wright, Les Hunaudières, near Le Mans, France. An Armée de Terre officer present as an observer, Captain Alexandre Sazerac de Forge, is on the left. Anon., “Wilbur Wright s’envole!” » La Vie au Grand Air, 5 August 1908, 130.

The crates containing the Wright biplane arrived at said factory around mid-June. Wright discovered to his horror that the aeroplane was in very poor condition. You see, in 1907, French customs officers had opened the crates to examine their content. That done, they had put the parts of the machine back into the crates any old how.

Wright had to work for several weeks to repair the damage caused by those incandescently intelligent individuals. Incidentally, his work habits and lack of pomposity greatly impressed Bollée’s employees.

As that work continued, Bollée observed what was happening and noted the somewhat crude appearance of the aeroplane’s engine. He could not help but offer a few suggestions, which Wright very often accepted.

The American perhaps accepted them all the more so since, during ground tests, he suffered serious burns to one arm and his chest when a rubber pipe which brought the hot water leaving said engine to its radiator burst while he was close by. Bollée instantly rushed to Wright’s assistance.

In any event, the modifications made to the engine contributed to the success of the increasingly spectacular demonstration flights that Wright carried out from August 1908 onward. The latter readily acknowledged Bollée’s help since day one.

Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée aboard the Wright Model A of Wilbur Wright, Camp d’Auvours, Champagne, France, near Le Mans, October 1908. Anon., Les Journées Léon-Bollée. (Angers: Éditions C. Hyrvil, 1920), unpaginated.

Indeed, Bollée took to the sky in October 1908. The daily L’Auto of Paris, France, jokingly mentioned that the flight in question constituted a record. No aeroplane in the world had until then carried such a heavy passenger. Bollée actually seemingly weighed nearly 110 kilograms (nearly 240 pounds).

At that time, Wright and Bollée were good friends, despite the fact that the latter did not speak English and that the former did not speak French either. By the way, Bollée’s heavily pregnant spouse, Karlóta Yiórgos “Charlotte” Bollée, born Messinesi, apparently played the role of interpreter.

If that was the case, one might wonder under what circumstances that lady of Greek origin learned English. A potential solution to that conundrum lied in the fact that several members of the Messinesi family were then living in London, England, including one who was none other than the Greek consul general, Léon Messinesi, a gentleman who might had been born in the same place as the spouse of Bollée, Aígio / Aigio, Greece, the town where Bollée and Messinesi apparently got married in April 1901.

And yes, you are right, my reading friend. Mrs. Bollée flew with Wright in October 1908, shortly after her spouse. She showed more courage than yours truly. I would not have taken to the sky in a Wright biplane for all the gold in Peru. And yes, she flew after the birth of her daughter, Élisabeth Bollée, in August.

When Wilbur left France at the beginning of May 1909, he was undoubtedly the best-known aviator in the world. The rest, as the saying goes, was history.

Please note that the following is very sad.

The French automobile pioneer that Léon Auguste Antoine Bollée was died in December 1913. He was barely 43 years old.

Mrs. Bollée then took the reins of the family firm, apparently renamed Usines Léon-Bollée sometime later. She oversaw the production of munitions and small arms during the First World War. The evolution of the firm would change profoundly from 1924 onward.

Anxious to increase its revenues, the well-known English automobile manufacturer Morris Motors Limited founded the Societé française des Automobiles Morris in October, with the aim of overseeing automobile sales in France. Said sales seemingly did not increase dramatically, however.

In December, Morris Motors therefore acquired Usines Léon-Bollée. The Société française des Automobiles Morris thus became the Société française des Automobiles Morris-Léon-Bollée. The production of new automobiles combining French and English know-how began perhaps even before the end of the spring of 1925.

This being said (typed?), the typical French motorist showed little enthusiasm for the idea of purchasing an automobile whose manufacturer was under foreign control. The name of the firm therefore changed again, in May 1931, to Société des Établissements Léon-Bollée. The link with Morris Motors was severed.

The Société des Établissements Léon-Bollée was one of the many firms around the world which succumbed to the blows of the Great Depression, however. It was liquidated in December 1934 or January 1935.

And I think that is all for today. Toodeloo.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)