A good swing deserves another: The saga of the Canadian Canadair CL-44 cargo plane, Part 1

Happy New Year, my long-suffering reading friend. Yours truly would like to enter this year 2022 of the common era, and no longer of the Christian era, with a not too boring topic. Indeed, let us not forget, the Christian peoples present on planet Earth represent only 30 % of the population of naked apes currently alive on Earth.

Why not start the year 2022 with texts concerning aviation? If I may paraphrase Homer Jay Simpson, out of context, aviation is the cause and the solution to many problems that affect humanity.

In 1952, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) set out on a search for a new maritime reconnaissance aircraft. It needed to replace the Canadian-made Second World War era Avro Lancasters it had used for that job, for lack of anything better, since 1950.

Need I tell you that the stunning collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Lancaster? I thought so.

A well-known aircraft manufacturer, Canadair Limited of Cartierville, Québec, a subsidiary of the American firm General Dynamics Corporation, 2 firms mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2018, was very interested in that quest. The cancelation of the production program of the Beech T-36 had cost it dearly, and ... And I was going to forget to tell you about that project somewhat forgotten these days. Ahhh.

In 1950, the United States Air Force (USAF) invited a number of firms to prepare proposals for a new twin-engine advanced training aircraft for the training of its navigators. Beech Aircraft Corporation won the competition in July 1951 but Canadair ranked among the firsts. Its efforts did not go unnoticed. As compensation, the USAF offered it to participate in the T-36 manufacturing program. In addition to supplying parts and sub-assemblies, the Québec aircraft manufacturer obtained contracts for 225 or so aircraft. This was the largest order ever granted to a foreign aircraft manufacturer by the USAF. By way of comparison, Beech Aircraft only had to build 195 or so T-36s, for a total of 420 or so aircraft.

There was nothing exceptional about such a division of the pie. At that time, the administration of president Harry S. Truman had a policy of sharing as much as possible the production of an aircraft between 2 aircraft manufacturers.

Discussions within the USAF regarding the use of turboprop engines instead of piston engines caused delays to the project. Unable to meet the new deadline, Beech Aircraft also had to call on several subcontractors. The costs of the program quickly increased. In early 1953, shortly after coming to power, the administration of President Dwight David “Ike” Eisenhower, a gentleman mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018, launched a broad, economically oriented strategic agenda. Its guidelines were clear: military spending had to be reduced.

Massive cuts forced the USAF to reassess the importance of ongoing programs. Combat aircraft understandably got priority and the T-36 looked a tad too luxurious. In June 1953, virtually a few hours before the prototype’s first flight, the United States Department of Defense put an end to the program. In the Cartierville factory, there was consternation. Overnight, many workers found themselves out of work, but back to the maritime reconnaissance aircraft the RCAF wanted to acquire.

Canadair submitted 2 preliminary proposals to the RCAF: one, entirely original, and the other, derived from the Bristol Britannia, a long-range British turboprop airliner which had first flown in August 1952. Whichever aircraft was chosen, everyone agreed that that program was going to be expensive.

Given the situation, the Department of National Defence wondered whether it might not be more economical to buy an American or British aircraft. Four aircraft manufacturers, including 3 American ones, submitted proposals. The RCAF nonetheless chose the modified version of the Britannia proposed by Canadair, designated the CL-28, in February 1954 – a decision which may have been taken, if only in part, to compensate for the abandonment of the production program of the T-36. The Department of Defence Production then ordered 13 CP-107 Argus. The RCAF, on the other hand, was hoping to obtain 50 such aircraft. Its hopes were dashed. A second order, for only 20 aircraft, followed in mid-1956.

The choice of the ARC was not unanimous. It was indeed difficult to manufacture a British aircraft using North American methods and personnel. Worse still, Canadair had to transform the very structure of the Britannia to adapt it to its new mission. This being said (typed?), Bristol Aeroplane Company Limited was supporting it in that work. The two aircraft manufacturers were so confident that Canadair did not even build a prototype. The first Argus flew in March 1957. A first delivery was made in May 1958. Between 1957 and 1960, Canadair produced 33 Arguses, a pretty small number. Still, the Argus proved to be one of the finest maritime reconnaissance aircraft of its time.

Need I tell you that the stunning collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes an Argus, or that Bristol Aeroplane was mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since June 2018? No? That is good.

A brief digression if I may. In November 1955, Bristol Aeroplane joined forces with Canadair and its sister firm, the Convair division of General Dynamics, to produce a much-improved derivative of the Britannia, then still under development. That fast and economical Super Britannia would compete with the jet airliners which were on the drawing board stage at the time. Anxious to prevent the acquisition of technical knowledge by General Dynamics, the government of the United Kingdom indicated in February 1956 that it was going to subsidise its design. If the American firm found itself excluded from the project for the moment, it was possible that its Convair division would receive a production license at a later date. Canadair was relegated to the level of secondary partner. For one reason or other, it did not take long for the Super Britannia to be abandoned.

And yes, the Convair division and General Dynamics were mentioned in several and many issues of our you know what since July and May 2018.

Another project just as big as the Argus began in 1956 when the RCAF asked Canadair to prepare plans for a modified and lengthened version of that aircraft to replace the Canadair North Star of its transport squadrons. In fact, the aircraft manufacturer had been working on an equivalent project for the civilian market for some time.

Even before the end of the year, Canadair tried to secure an order from Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA), in 2022 Air Canada Incorporated. Deeming the CL-44 too big, the national air carrier ordered a British aircraft, the Vickers Vanguard. Canadair’s management protested, without success. Canadian Pacific Airlines Limited, the nation’s largest private airline and a subsidiary of a Canadian transportation giant, Canadian Pacific Railway Company, did not show any more interest.

And yes, again, Canadian Pacific Airlines and Canadian Pacific Railway have been mentioned in many issues of our yadda yadda since April 2019. TCA, on the other hand, was mentioned many times since August 2017.

Some American airlines specialising in freight transport showed more enthusiasm. They wanted the new aircraft to be easier to load and unload, however. During discussions, someone suggested that it be provided with a swing-tail. Canadair thought the idea was excellent.

And yes, you read it right. The someone had suggested that the entire tail section of the CL-44 cargo plane be hinged so that it could be opened to load and unload large items quickly.

The Department of Defence Production signed a contract for 8 Canadair CC-106 Yukon transport planes fitted with a side door for the RCAF in April 1957. That was not much. It therefore ordered 4 additional aircraft. When signing the first contract, Canadair agreed to prepare plans for a swing-tail version of the CL-44 intended for the civilian market. The Department of Defence Production defrayed the costs of developing and manufacturing the first example of that extremely innovative aircraft. Canadair was so confident that it did not manufacture prototypes for the military or civilian versions of the CL-44.

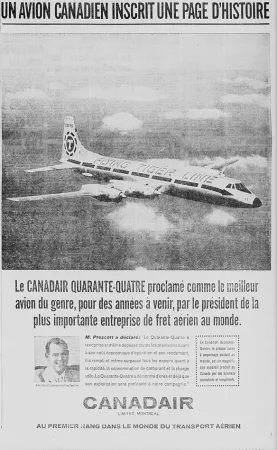

Also in April 1957, Canadair and Bristol Aeroplane signed an agreement under which the Québec aircraft manufacturer could export the Argus and CL-44 anywhere in the world, with the exception of the United Kingdom for the CL-44. Building on these successes, the Québec firm launched a vast promotional campaign.

The first Yukon took to the sky in November 1959. The first civilian cargo aircraft followed in November 1960. This time, Canadair seemed to have hit the jackpot. The 3 largest American airlines specialised in the transport of cargo, that is Flying Tiger Line Limited, Seaboard and Western Airlines Incorporated and Slick Airways Incorporated, had in fact voted in favour of the swing-tail CL-44 even before the aircraft’s first flight. Two of them signed contracts in May 1959, for example. It should be noted that 11 of the 17 aircraft delivered to these firms in 1961-62 could carry freight and passengers.

In the spring of 1960, the Pakistani government expressed interest in ordering 3 to 5 swing-tail CL-44s for its national carrier, Pakistan International Airlines, or its air force, the Pāk Fìzāʾiyah. These cargo planes would greatly facilitate links between West Pakistan and East Pakistan, in 2022 Bangladesh, separated from each other by India. Keen to help Canadair, the federal government approved financial arrangements to help Pakistan pay for the aircraft. The Department of External Affairs refused to grant an export permit, however, for fear of offending the Indian government. Offending the Pakistani government was not deemed to be as important, because of its ties with the People’s Republic of China perhaps, but I digress.

While talks about the proposed sale to Pakistan were continuing, apparently, Canadair received a visit from a Saudi businessman. He explained that the CL-44 could prove very useful in Saudi Arabia, for various reasons (deliveries of water to isolated communities, transport of fruits and vegetables imported from Ethiopia and / or transport to Mecca of pilgrims living in distant lands). Representatives of Canadair met with the Saudi Minister of Defence, quite possibly Muḥammed bin Suʿūd Āl Suʿūd, who informed them that Saudi Arabian Airlines was in fact considering ordering 2 to 5 CL-44s which would in all likelihood be maintained by Pakistan International Airlines. The failure of the Pakistan sale plan ended talks with the Saudi government.

Canadair also hoped to sell a number of swing-tail CL-44s to the USAF through a bilateral agreement, a hope detailed in the second part of this article.

However, the agreement signed in June 1961 excluded the CL-44 in favour of a contract for 140 Lockheed F-104 Starfighter supersonic fighters. While the Québec aircraft manufacturer was delighted with that order, both its management and the Department of Defence Production certainly realised its impact on future sales of the CL-44.

During the summer of 1961, the two sides came to an agreement which should avoid the closure of the CL-44 assembly line. Through that agreement, Canadair agreed to finance the manufacture of 4 swing-tail CL-44s. The federal government did the same, for 5 aircraft. Better yet, it agreed to accept these CL-44s if Canadair could not sell them. The challenge was big. The aircraft manufacturer recontacted many potential customers, both in Canada and abroad. One of these was particularly noteworthy.

In early 1961, TCA obtained federal government permission to purchase 5 Douglas DC-8 jet airliners. As air traffic had declined, the Canadian national air carrier reduced its order to 4 aircraft. A little later, TCA replaced these DC-8s with DC-8 Jet Traders, a convertible aircraft capable of carrying freight and passengers. Canadair protested, thus embarrassing the federal government. In November, Finance Minister Donald Methuen Fleming refused to approve the order. TCA’s operating budget for 1961 had already been approved, he said.

The president of TCA, a fighter pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War, did not believe that explanation. Gordon Roy McGregor was right. Canadair had stepped up to get a contract. Its argument was simple. If TCA, a crown corporation, ignored the national interest and refused to buy a Canadian product, who would? The very reputation of the CL-44 was at stake. That reasoning did not stand up to close examination, however. Indeed, if TCA reluctantly purchased CL-44s, some potential foreign customers might have questions about the performance of the Canadian cargo plane.

The positions of TCA appeared to be much stronger than those of Canadair. The air carrier already has 10 or so DC-8s used for passenger transport. Its new Jet Traders would allow it to gradually enter the air freight business without having to introduce a new type of aircraft to its fleet. Best of all, the Jet Trader flew both farther and faster than the CL-44. It was also more versatile. In fact, the entire board of directors of the firm challenged the federal government by approving the purchase of the Jet Traders. In December 1961, the Cabinet approved the purchase of these aircraft.

Canadair faced a similar situation when it tried to promote the CL-44 to major airlines, which, let us not forget, carried the bulk of the cargo delivered by air. Like TCA, these airlines had investing heavily in the purchase of popular jet airliners. In fact, they had invested such sums that it was often impossible for them to order specialised cargo planes. Worse still, they had bought too many aircraft which often flew half empty. Air freight thus became a lifeline.

Sensing a good deal, Boeing Airplane Company and Douglas Aircraft Company Incorporated were quick to offer convertible versions of the Boeing Model 707 and Douglas DC-8 which could accommodate both passengers and cargo. All these jets were fitted with a side door. Airlines in fact preferred that solution to the swing tail, which was more efficient but also more complex and too specialised.

This being said (typed?), the truth is that both Boeing Airplane and Douglas Aircraft worked on swing tail derivatives of their Boeing Model 707 and DC-8 jetliners. Neither of these machines went beyond the design stage.

Would you like to read that Boeing Airplane was mentioned in issues of March and December 2021 and that Douglas Aircraft had been several / many times since July 2018. All right, all right, let us not get angry.

As 1962 began, Canadair had sold the 4 swing-tail CL-44s it had financed out of pocket. The 5 federally paid aircraft and the very first swivel tail CL-44, however, remained unsold. Worse still, no help would come from the federal government. Severely shaken by the loss of its majority in the House of Commons following the general election of June 1962, the party in power no longer wanted to help Canadair. The aircraft manufacturer managed to sell 2 aircraft but a few potential customers vanished into thin air. Canadair and the Icelandic national carrier, Loftleidir Hlutafelag, initialed an agreement in February 1964, however. The aircraft manufacturer lengthened the fuselages of 4 CL-44s and transformed them into airliners.

Loftleidir, which was not a member of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), a private organisation which represented and served most of the world’s air carriers, used its new aircraft to provide its customers with low-cost transatlantic flights. Outraged by these actions, the members of IATA limited as much as possible its access to European and North American airports. The young, travel-hungry clientele which used Loftleidir’s services, however, did not give much of a hoot about the opinion of IATA and its members. This earned the Icelandic airline the nicknames “Hippie Airline” and “Hippie Express.”

A last-ditch effort by Canadair to sell to charter airlines a production version of its stretched and extremely economical airliner, the Canadair CL-400 / Canadair 400 / Canadairbus, failed.

Between 1959 and 1965, Canadair manufactured 39 CL-44s: 12 used by the RCAF and 27 by air carriers.

A sad scene in that story had taken place in April 1962. Unable to accept the decision of TCA and the federal government, the aircraft manufacturers withdrew from the Air Industries and Transport Association of Canada and founded the Air Industries Association of Canada, in 2022 the Aerospace Industries Association of Canada. Left to their own devices, the airlines set up the Air Transport Association of Canada.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)