A look under the hood of one of the symbols of the West German economic miracle of the 1950s; or, The multifaceted and multinational tale of the Isetta microcar, part 2

Buongiorne, amico lettore, buongiorno e benvenuti a questa seconda e ultima parte del nostro articolo su un uovo italiano su ruote, l’Iso Isetta.

You will remember that this Italian microcar was mainly produced in West Germany. This being said (typed?), that country was not the only one where an assembly line was set up, which explains in part the several nicknames given to the Isetta:

in West Germany, rollende Ei (rolling egg);

in Argentina, ratón alemán (German mouse);

in Brazil, bola de futebol de fenemê (soccer ball of the FNM);

in Chile, huevito (small egg); and

in France, pot de yaourt (jar of yogurt).

For your information, the Fábrica Nacional de Motores (FNM) was a Brazilian state company founded in 1942 which manufactured automobiles and trucks. Said company terminated its activities in that field at an undetermined date during the 1970s or 1980s.

Let us begin immediately our overview of places other than West Germany where Isettas were made under license.

Iso Autoveicoli Società per Azioni, the Italian firm which initially put the Isetta on the market, sold a production license for its microcar to a Spanish firm created for that purpose. Iso Motor Italia Sociedad anónima produced, or assembled, around 1 000 Isettas between 1953 and 1959. Some of these vehicles may, I repeat may, have had 3 wheels and not 4.

Also in 1953, Iso Autoveicoli sold another production license for his microcar to a French firm apparently created for that purpose. The purchase and installation of brand new production tooling having taken a certain time, VELAM (Société anonyme?), an acronym for VÉhicule Léger À Moteur, did not begin production of a modified Isetta until 1955. Despite a network of around 150 dealers all over France, the VELAM Isetta sold poorly. It was actually considered noisy. Worse still, it cost a tad too much.

VELAM tried to boost its sales by launching a convertible Isetta in 1957. The French consumer was unfortunately not interested. Various records set in an automobile racetrack did not increase his interest any further. Even the VELAM Écrin, a luxury version of the microcar launched in 1957, left the French consumer largely indifferent. The last microcar produced by VELAM left the shops in 1958.

Nobody seemed / seems to know the exact number of vehicles produced by the French firm. The numbers vary between 4 000 and 7 100 Isettas / Écrins.

The commercial failure of the French Isetta could probably be explained in various ways. Its motorcycle engine was not ideal for an automobile and it required frequent maintenance. The French consumer who could afford an automobile also wanted to buy a vehicle which was more comfortable, larger, faster and more robust than the Isetta or Écrin.

It should be noted that VELAM and Bayerische Motoren Werke Aktiengesellschaft (BMW), the German firm which then produced its own versions of the Isetta, a firm mentioned in the first part of that article, considered, in 1958, the possibility of producing a Franco-German version of that vehicle fitted with a French chassis and a German engine. That first (?) example of European cooperation in the automotive sector unfortunately did not lead to anything concrete.

A small and slightly amusing detail if I may. The American feature film Funny Face, a romantic musical released in theatres in 1957, included a scene during which the great Fred Astaire, born Frederick Austerlitz, took the wheel of a VELAM Isetta.

In December of that same year, an American actor and singer you may know, a certain Elvis Aaron Presley, offered a red BMW 250 or 300 to his impresario, Thomas Andrew Parker, born Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk. The “King,” on the other hand, preferred to drive a brand-new BMW sports car. One had / has to wonder if Parker was amused.

Another small media detail, televisual in that case, if I may. A key character in the American situation comedy Family Matters (1989-1997), the brilliant and clumsy Steven Quincy “Steve” Urkel, learned to drive at the wheel of a BMW 250 or 300 which he used regularly thereafter, but I digress.

In 1955, Iso Autoveicoli sold a production license for its microcar to a Brazilian machine tool manufacturer. Indústrias Romi Sociedade anônima and the Brazilian government believed that a microcar like the Isetta would be an ideal urban vehicle. In fact, the Isetta was one of the first mass-produced automobiles in Brazil. This being said (typed?), the Brazilian government reconsidered its offer, or promise, to financially support the production project of Indústrias Romi. The Brazilian firm, however, produced around 3 000 vehicles between 1956 and 1961.

In 1957, a British firm specialising in the manufacture of glass fiber reinforced plastic bodies and chassis for automobile kits, Ashley Laminates Limited, considered producing the Isetta, in one form or another, but soon abandoned that project. Another British firm might, I repeat might, indeed have beaten it to the post.

Indeed, BMW sold a license to produce the BMW 300 to Dunsfold Tools Limited, a tool maker, it seemed, which became Isetta of Great Britain Limited in March or April 1957. The former locomotive factory used to manufacture these vehicles, which were known as Isettas and not BMWs, a factory redeveloped according to the guidelines of BMW say I, was on top of a cliff, however. It had no road access, apart from a road at the foot of a staircase which had a good hundred steps and … I am not kidding. Seriously.

While most of the parts and sub-assemblies delivered by BMW certainly did not require road access, dealers were forced to pick up the Isettas on order at a train station near them.

The first thousand Isetta 300s, and not BMW 300s, produced in England were in fact intended for the Canadian market. These automobiles apparently had reinforced bumpers and a beefed-up heating system. If the latter item was understandable, the former leaves me a tad perplexed. Considering the difference in size between an Isetta and a typical ginormous North American automobile of the era, what driver would be crazy enough to even think of any contact between these vehicles? That size differential was the very reason behind the new bumpers, you say, my perspicacious reading friend? Good point.

It went / goes without saying that the Isetta 300s intended for the British market had a steering wheel mounted on the right side, a seemingly innocuous detail which nevertheless posed a problem. You see, the Isetta’s engine was also on the right side. Restoring the correct balance of the vehicle therefore entailed placing a counterweight weighing approximately 27 kilogrammes (60 pounds) in the chassis, on the left.

The Isetta 300 initially sold quite poorly. Road legislation and taxation then came to the rescue of Isetta of Great Britain. A 3-wheeled Isetta was indeed classified as a 3-wheeled motorcycle, a lower-taxed vehicle which only required a motorcycle driver’s license to drive. A production shift to 3-wheeled vehicles led to a non negligible increase in sales.

Yours truly do not know if the Isetta 300s shipped to Australia and New Zealand had 3 or 4 wheels.

This being said (typed?), Isetta-type utility vehicles made in England presumably had 4 wheels, not 3 – for safety / stability reasons.

BMW took control of the British factory in the early 1960s. The last vehicle left the premises in 1964. I must admit that I do not know how many Isetta 300s took the train between 1957 and 1964.

Isetta Motors of Canada Limited, the Canadian distributor of the Isetta, was born in Toronto, Ontario, no later than 1957. It was in all likelihood around that time that it really became possible to buy an Isetta on Canadian soil, using the services of a local dealer. Just think of City Motors Limited of Montréal.

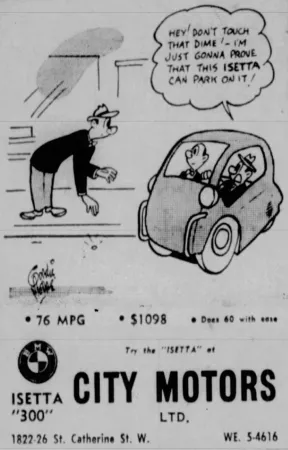

To that effect, allow me to mention a trio of amusing advertisements concerning the microcar manufactured by Isetta of Great Britain which were published in 1957 by City Motors in a major English-language daily newspaper in Montréal, The Gazette. Their texts read as follows:

Hey! Don’t touch that dime! – I’m just gonna to prove that that Isetta can park on it!

Bring the eye dropper Joe – Here’s another Isetta to fill up.

Hey! You’ve only got about half a drop of gas left. / Oh! That’s fine – We’ve only got a little over [160 kilometres] a hundred miles to go.

Two of the texts above reminded potential buyers that all versions of the Isetta consumed very little gasoline: around 3.7 litres/100 kilometres (around 76 miles/Imperial gallon / around 63 miles/American gallon) according to some.

Yours truly dares to hope that you will have noted, my equally distracted and attentive reading friend, that the drawing mentioning the dime was the illustration which adorned this edition of our fabulous blog / bulletin / thingee.

The artist behind the humorous drawings was Gordon Chapman “Gordie” Moore. His great creation was a much-loved humorous comic strip depicting daily events taking place in Montréal. Around our town first appeared in August 1945, in The Gazette. Over the years, two of Moore’s main punching bags were undoubtedly the Montreal Tramways Company and the Montreal Transportation Commission, which acquired the assets of the former in 1951. Around our town disappeared in June 1962 following the death of Moore, about 5 weeks before his 43rd birthday, which was a real shame.

However, let us resume the course of our story on Canadian soil.

Also in the late 1950s, at least one Alberta distributor, Nance Company, used somewhat flashy terms to describe the British Isetta 300s it offered to consumers: “Alberta’s ISETTA ‘SPUTNIK’ Is Here TODAY! Is Here To STAY! The Motor Car That’s Just ‘Out Of This World’”

The (short-lived?) Ottawa, Ontario, area dealer, Isetta Sales & Service (Incorporated? Limited?) used similarly spacey terms: “Flying saucers? Invasion from outer space invasion? No! These are the world famous ISETTAS – NOW in Ottawa.”

Incidentally, the Isetta 300 sold for between $ 1 100 and $ 1200 on Canadian soil around 1957, or between $ 10 700 and $ 11 700 in 2022 currency.

In 1959, an Argentine firm acquired the production license for the BMW 600, an elongated version of the Isetta mentioned in the first part of this article. Metalmecánica Sociedad anónima industrial y comercial manufactured just over 1 400 De Carlo 600s between 1959 and 1962.

All in all, 6 firms around the world produced a little less, or a little more, than 175 to 180 000 Isettas, all versions included, between 1953 and 1964.

Is that the end of the saga of the Isetta and of this peroration? Nay. I am not done with you yet.

In 1996, a recently formed British firm, specialising until then in the manufacture of parts for owners of vintage microcars, began production of a 4-wheeled Isetta clone with a modern motorcycle engine and a fibreglass body, a clone which included some equally modern elements and sub-assemblies as well as, it seemed, some parts from original vehicles. Tri-Tech Autocraft UK Limited produced just over 15 Tri-Tech Zettas between 1996 and 2001. Some of these vehicles may have been delivered in kit form, costing £ 2 650, which was a bargain compared to the price of a ready-to-run Zetta, which came in at £ 9 450 – values which equated to over $ 6 900 and over $ 24 600 respectively in 2022 currency. And yes, I share your opinion, that was a tad pricey for an egg on wheels. Tri-Tech Autocraft UK ceased operations in the early 2000s.

A few years later, in 2008 to be more precise, BMW considered the possibility of producing a completely modernised electric version of the BMW 250 and 300. That urban microcar, however, did not go beyond the project – or prototype – stage.

In 2016, a Swiss firm, Micro Mobility Systems Aktiengesellschaft, presented the proof-of-concept prototype of an electric clone of the Isetta at the Salon international de l’automobile de Genève. Designed in collaboration with Designwerk Technologies Aktiengesellschaft and the Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, a Swiss specialist in electric mobility and a Swiss university of applied sciences, the Micro Microlino was aimed at urban populations, in all likelihood trendy / connected people. No pun intended. Well, maybe a little. It was to sell for around € 12 000, or around $ 16 200 in 2022 currency.

In 2019, Micro Mobility Systems signed an agreement with Centro Esperienze Costruzione Modelli e Prototipi Società per azioni, or CECOMP, according to which the Italian firm undertook to manufacture the Microlino. The coronavirus disease 2019 slowed down the marketing of the vehicle, however, the production of which seemingly did not begin until 2022. Indeed, 7 dealers located in 5 countries (France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Switzerland) were looking forward to your visit, my reading friend.

Meanwhile, a clone of the aforementioned BMW 600 appeared in 2018. Sūzhōu Yīng Diàndòng Chē Zhìzào Yǒuxiàn Gōngsī’s Eagle was expected to sell for around ¥ 32 000, or about $ 7 400 in 2022 currency. The Chinese electric automobile maker seemed to give up on that project between 2018 and 2022, however.

And that is all for today.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)