It was indeed one heck of a brand: Fred Magee, Fred Magee Limited of Port Elgin, New Brunswick, and their Mephisto brand products – not to mention a few words on the Canadian lobster industry, part 2

Greetings and salutations, my reading friend. You will of course remember the main topic of this week’s issue of our ever so fascinating blog / bulletin / thingee. Yes, we are indeed looking at the life and times of New Brunswick financier / industrialist / philanthropist and vocational education pioneer Fred (Frederick?) Magee, a gentleman well known in his time for the production of canned lobster by his firm, Fred Magee Limited of Port Elgin, New Brunswick.

By 1918, Canada’s overseas lobster markets had all but disappeared. Experiments were therefore conducted to see if live lobsters could be sent to inland cities like Ottawa, Ontario, by train. A shipment arrived in the national capital in mid June, from the Gaspé peninsula of Québec, for example. Most of the 400 or so lobsters appeared to be in good condition upon arrival. They were immediately placed on the market, a prelude to their untimely death by boiling. That experiment might, I repeat might, have led to further deliveries.

The catch of course was that lobster had become so expensive that only well-off people felt comfortable at the idea of buying some. Transporting those crustaceans by train probably did not help their price either.

In any event, some researchers were raising the alarm as to the long-term survival of the lobster fisheries. Allowing fishermen to go out to sea during the spawning season and catch females loaded with thousands of eggs made no sense, stated the chairperson of the Biological Board of Canada, Archibald Patterson Knight, a professor (biology and physiology) at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. The long-term survival of the resource should take precedence over the wishes and convenience of the canners and fishermen. Politicians should be looking at the big picture, and…

I know, I know, the man’s naivete was quite touching, but back to our story.

In a report completed during the summer of 1919, after visiting the lobster fishing regions of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, Knight stated that many assumptions commonly held by canners and / or fishermen bore no relation to reality. Nothing proved that lobsters were evenly distributed along the Atlantic coast of North America and it was indeed possible to exterminate the species. Indeed, catches were decreasing almost on a yearly basis.

According to Knight, the lobster fishing season should be shortened, and sanctuaries should be established where no fishing whatsoever should be allowed.

And yes, a fine not exceeding $ 1 000 could apparently be imposed on any fisherman found in possession of a spawning female lobster. The catch was that hardly anyone knew of anyone who had been so fined. That sum, by the way, corresponded to approximately $ 17 000 in 2024 currency.

Earlier that summer, yes, the summer of 1919, another member of the Biological Board of Canada and biology professor at Queen’s University, William Thomas MacClement, toured Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island with a Reverend MacGillivray to acquaint the fishermen with the results of the research conducted by the board. The latter generally showed a willingness to act in accordance with the conclusions of said research.

Incidentally, yours truly wonders if the aforementioned Reverend MacGillivray was not Donald MacGillivray, a famous Canadian protestant missionary / newspaperman / philanthropist / publisher / scholar who, after years spent in China, was spending some time on furlough in Canada, but I digress.

And no, my ever-eager reading friend, MacGillivray was apparently not related to Father John “Jack” MacGillivray, a Royal Canadian Air Force roman catholic chaplain and aviation enthusiast who sold his de Havilland Puss Moth private plane to what was then the National Aviation Museum, in Ottawa, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, but back to the Canadian lobster industry in 1918-19.

From the looks of it, certain regulations were instituted, but no sanctuary was established. Even so, an educational campaign carried out for the benefit of the fishermen resulted in some useful results.

The end of the First World War did not bring about an immediate improvement in the fortunes of the Canadian lobster industry.

In the spring of 1920, representatives of the 3 largest canning firm located in the Maritime Provinces visited the United Kingdom, France and Belgium, 3 countries which accounted for ¾ of Canada’s lobster exports. The comments they made upon their return home, in April, were not very reassuring.

Exchange rate issues meant that many, if not most European brokers, including those in the United Kingdom of course, did not take delivery of the lobster shipped to their respective countries. As a result, mountains of cans piled up on wharves. This, of course, meant that canners ran the risk of losing a lot of money.

Even though things gradually improved as European economies began to regain their footing, the industry was still smaller than it had been before the First World War. In 1923, for example, the 600 or so canneries employed less than 6 000 people. Even though the number of people employed hovered around 6 200 in 1927, the number of canneries had dropped by more than 25 %, to 440 or so. In 1929, only 355 or so canneries were left – half the 1913 figure.

This being said (typed?), higher sales prices meant that the annual value of the lobsters marketed, either alive or in cans, hovered in 1923 around $ 1 350 000, a sum which corresponded to approximately $ 23 000 000 in 2024 currency. That same value went down 10 % in 1924.

One had to wonder if the fact that several European customers were not all that pleased with the quality of some of the canned lobster imported from Canada could explain the lower value experienced in 1924.

And yes, the earnings of the canneries’ staff and of the fishermen remained ridiculously low.

For whatever reasons, larger catch, improved quality, etc., the output of the lobster industry hovered around $ 3 180 000 in 1929, a sum which corresponded to approximately $ 55 000 000 in 2024 currency.

As the Great Depression began to bite, unemployment in Canada rose sharply. In the Maritime provinces, a number of men turned to fishing to make ends meet. Initially, catches became larger, and prices fell. Worse was to come, however. From 1932 onward, catches became smaller, but back to the person at the heart of this article.

It should be noted that Magee was one of the members of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick, on the government side, who was elected as a result of the February 1917 general election in that province.

Magee became the founding chairperson of the Vocational Education Board of New Brunswick in July 1918. Indeed, he had played a crucial role in the creation of said board. Magee seemingly held his position until 1925.

Oddly enough, he was appointed Minister without portfolio a week or so before the October 1920 general election.

Re-elected at that time, Magee served as Minister without portfolio. He became President of the Executive Council, the province’s cabinet, in February 1923. Magee lost his seat when his political party was thrown out of office as a result of the August 1925 general election.

Oh, before I forget, Fred Magee, yes, the firm, was canning chicken no later than 1921. I kid you not, but I do wonder if issues with the lobster catch forced the firm to reorient its activities a wee bit. And no, I have no idea of when that product line was removed from the market.

And now for something for something completely different.

Magee knew from personal experience that many young people did not recognise themselves in the standard and academically oriented curriculum offered in New Brunswick’s educational system. He set out to change that, with the help of a career civil servant, the Director of vocational training for New Brunswick, Fletcher Peacock. It might be argued that it was mainly through Magee and Peacock’s common initiative that vocational training came of age in New Brunswick.

And yes, many if not most owners / operators of private commercial / vocational schools located in New Brunswick strenuously opposed Magee and Peacock.

In any event, it was thanks to them that the Saint John Vocational School of… Saint John, New Brunswick, one of the first educational institution of its type in Canada, opened its doors, in 1926.

Fred Magee became Fred Magee (New Brunswick) Limited of Port Elgin in January 1927. Magee continued to occupy the positions of President and Manager of that curing / dealing / packing / producing firm. Yours truly cannot state if that somewhat complex corporate name was used a lot, instead of plain old Fred Magee.

Despite the difficult economic climate of the 1930s, the infamous decade of the Great Depression, despite also some years during which the lobster catches were deplorably small, between 1933 and 1935 for example, I think, Magee’s firm did rather well. By then, it distributed the canning equipment produced by a few firms and produced cans for various local and regional firms, all the while producing canned lobster of course.

Even though several if not many of his competitors had to throw the towel, Magee enlarged his Pictou, New Brunswick, plant. You see, the canny Magee had conducted canning experiments in previous years, with non seafood products like vegetables and fruits, apparently strawberries, at the Port Elgin cannery.

Given that his Pictou cannery was only active during the short (May-June?) lobster season, Magee enlisted the help of several farmers in the Pictou area in the summers of 1935 and 1936 in order to test various varieties of peas. The results were promising enough to convince Magee to launch the canning of peas and, later on, green beans. Before too, too long, more than 100 farmers were shipping their peas and green beans, as well as, later on, yellow string beans, to the Pictou cannery.

And yes, those vegetables carried the famous Mephisto label.

Would you believe that Magee, or one of his people, saw to it that the plant material left over after canning be turned into silage – and sold?

Would you also believe that, when the federal government became the majority owner of the Bank of Canada, in June 1936, I think, Magee became one of the directors of that private, yes, yes, private, institution, in September? He occupied that position until his replacement as New Brunswick’s representative, in February 1948, ten or years after the bank became a Crown corporation.

As might have been expected, the onset of the Second World War, in September 1939, once again played havoc with the markets of the Canadian lobster industry. After all, something like 85 % of its production had gone to Europe before the conflict. Indeed, the British government might, I repeat might, have terminated imports of lobster during the fall of 1939.

This time around, however, the federal government indicated, in early May 1940, that it would help the lobster industry, an industry which employed at the time 20 000 or so fishermen and cannery employees.

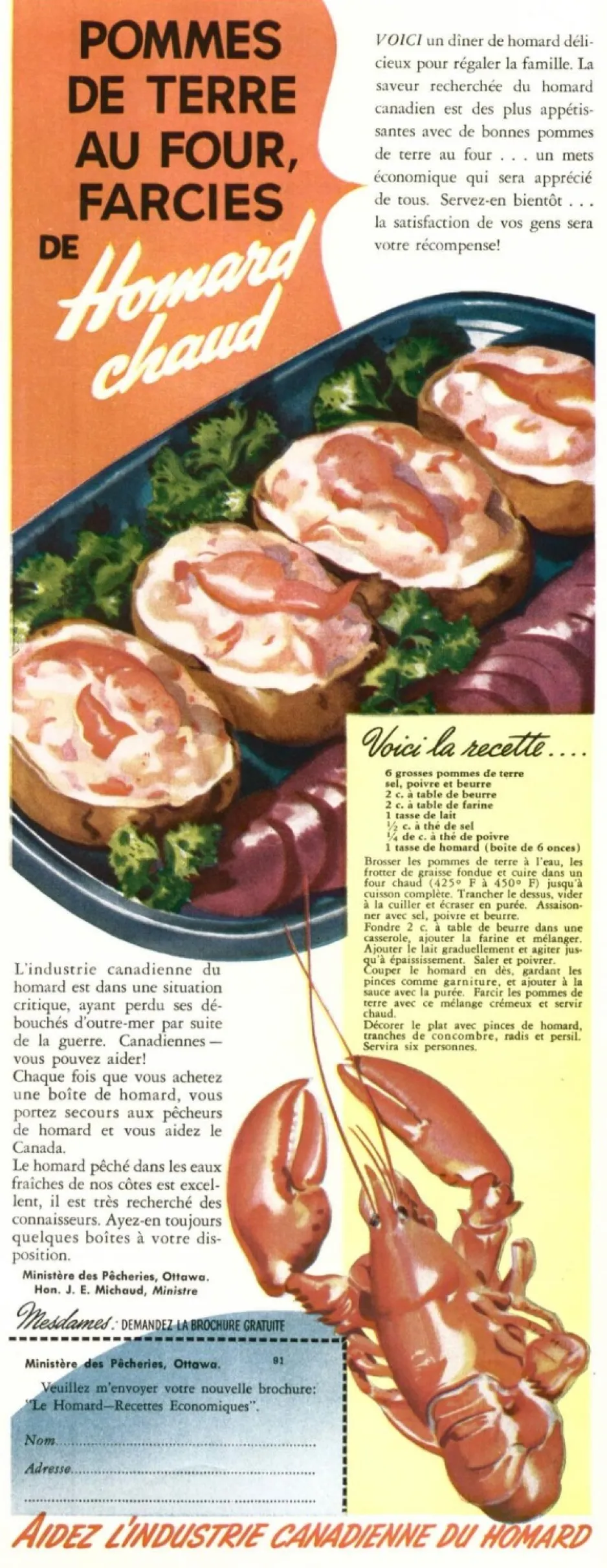

The Minister of Fisheries, the New Brunswick attorney / notary Joseph Enoïl Michaud, appointed an acting Lobster Controller that same month and took measures to ensure that fishermen receive a minimum sum for each unit of weight (kilogramme or pound, your choice) of lobster caught off Canada’s East coast.

By any chance, did I mention in the first part of this article that the American / Atlantic / Canadian / Maine / northern / true lobster can only be found on the Atlantic coast of Canada? No? Sorry. That decapod cannot be found on the Pacific coast of Canada, but it was not for lack of trying. Indeed, would you believe that, between 1896 and 1966, there were more than 10 separate attempts to introduce that lobster in British Columbian waters? I kid you not.

This being said (typed?), a few American / Atlantic / Canadian / Maine / northern / true lobsters have been caught in those waters in recent years. It has been suggested that those crustaceans had been released by animal lovers who had bought them in fish shops in order to set them free, but back to our story.

The federal government bought a good part, if not most of the 1940 lobster catch, and this in order to preserve the revenues of the industry and allow customers to buy lobster at a reasonably low price. It also bought a good part of the 1941 catch.

As was to be expected, that particular example of government intervention was very much to the liking of the Canadian lobster industry, which had not always held warm and fuzzy feelings toward such interventions.

Said acting controller was the Deputy Minister of Fisheries, by the way. Donovan Bartley Finn was seemingly confirmed in his functions in June or July 1940.

By then, the situation in Europe had changed a great deal, and for the worst. National Socialist Germany reigned supreme on the Western half of that continent, having successfully attacked several countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Luxemburg, Netherlands and Norway) in May and June. As well, the United Kingdom was besieged.

Exporting lobster to countries under German control was of course out of the question.

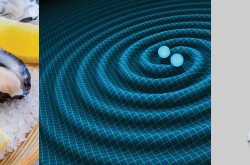

A typical advertisement of the Department of Fisheries for its Canada Brand lobster. Anon., “Ministère des Pêcheries.” La Revue moderne, September 1940, 59.

All but deprived of its overseas export markets, the federal government launched an intense sales campaign to boost lobster sales in Canada and the Unites States, and this in September 1940. There were advertisements in all sorts of magazines and newspapers, from coast to coast. Radio stations also contributed to that ballyhoo. Mind you, grocery stores soon followed with their own newspaper advertisements.

The federal government’s lobster advertising campaign differed from previous ones in one significant aspect. It was quite overt about the social implications of purchasing a can of lobster: “Women of Canada – you can help!,” stated one advertisement. “Be Patriotic! Serve Lobster,” stated another.

French language advertisements might not have been so blatant, however. “Help the Canadian lobster industry,” “Buy canned Canadian lobster” and “Lobster is a chic dish,” translations of course, were not exactly war cries. I mean, those sentences did not even end with exclamation marks.

Mind you, advertising firms in Québec undoubtedly knew that support for the war effort was a tad lukewarm in various francophone circles of that province. Let us not forget, the United Kingdom was a foreign country to them, not the mother country. France itself was to a large extent a foreign country. After all, the ancestors of Québec’s francophone majority had left that place no later than the 1750s.

This being said (typed?), recipes found in French language publications like the weekly magazine Le Samedi might have been a tad more intriguing. One only needed to mention the soufflé de homard au Kellogg’s Rice Krispies. Yummy…

All right, all right, the puffed rice grains in boxes of Rice Krispies are not as bad for you as a number of other breakfast cereals. Even so, the white rice from which that product is derived consists of almost 100% carbohydrate, with almost no fiber or protein, but I digress.

All in all, the federal government spent approximately $ 100 000 on lobster advertisement in 1940 and 1941, a sum which corresponded to approximately $ 2 000 000 in 2024 currency. Not a huge sum, actually.

An additional aspect of the federal government’s effort was the creation of a new and unique brand of lobster, the Canada Brand, which made its appearances on grocery store shelves from coast to coast in the fall of 1940. Over time, that brand came to account for 12% of Canada’s lobster sales.

And yes, the advertising campaign seemed to work. According to the aforementioned Finn, 1941 Canadian lobster sales were almost 5.7 times larger than those before the onset of the Second World War. More importantly, given the size of that market, 1941 American lobster sales were 5 times larger than those before the onset of the conflict. Wah!

It should be noted that sales of Canadian lobster to American buyers were helped by the fact that, when Japan attacked the United States, in December 1941, all imports of cheap canned Japanese crab meat to the North American continent came to a crashing halt.

Mind you, it is worth noting that a very large proportion of the canned lobster bought by the federal government in 1940-41 was served to members of the Canadian armed forces stationed on Canadian soil.

By 1942, the industry was said to be booming. The number of fishermen involved had gone down, many of them having enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy, but individual earnings had gone up. Even so, catches tended to fluctuate: a drop of 22.5 % from 1939 to 1940 and an increase of 8.5 % from 1940 to 1941.

Canada Brand canned lobster was available in 3 categories, Fancy, Choice and Standard. The meat of that latter category was neither firm nor bright coloured, for example. It could be used in chowders and bisques.

Such a grading system had not existed before the inset of the Second World War, a lack which might have discouraged some potential customers from buying the product.

Mind you, packs of frozen lobster were available. There were also live lobsters available for sale in a number of Canadian and American cities. New victims, sorry, sorry, new lobsters arrived almost every day by train.

I know it is quite hypocritical for me to feel that way, after all, I do love my medium rare filet mignon, but the idea of picking up an active and feisty lobster in a fish store so that I can boil it to death at home is not my cup of tea, but back to our story.

It is worth noting that any Canadian household requesting a copy of a government-published booklet entitled Economical Lobster Recipes, in French Le Homard – Recettes économiques, both of them published around July 1940, would get one free of charge. Well, for the price of a 3-cent stamp actually. Those 3 cents corresponded to approximately 61 cents in 2024 currency, which is lot less than the $ 1.15 (!) that you and I have to cough up now to mail a letter.

Still, things could be a lot worse. You and I could be British citizens, for example. Would you believe that people in that European country have to cough up the equivalent of about $ 2.35 in 2024 Canadian currency to mail a letter? I kid you not. In 2020, those people had paid the equivalent of about $ 1.65 in 2024 Canadian currency. Wah!

Another typical Department of Fisheries advertisement which sang the praises of the ‘Canada’ lobster brand. Anon., “Ministère des Pêcheries.” La Revue populaire, September 1940, 20.

If I may, yours truly would like to know why, from the looks of it, the lettering on cans of Canada Brand lobster seemed to be in English only. And yes, yours truly realises that the first federal Official Languages Act, an act which declared that English and French were the two official languages of Canada, came into force only in September 1969, but still. And I digress.

Incidentally, did you know that 3 out of every 4 Indigenous languages in the settler state known as Canada are endangered?

From the looks of it, the 1940 lobster catch was sold in Canadian and American grocery stores, and this at a good price. The relatively small size of the 1941 catch meant that federal government purchases were relatively small that year. Even so, it spent a lot of money in advertisement, which did not go unnoticed, as you might imagine. The aforementioned Michaud had to defend himself, and his department.

The end of the Second World War signalled the end of the Canada Brand of lobster, provided of course that said product had not vanished earlier. Life went on, even though many of the fishermen who had served in the Royal Canadian Navy never came home.

Incidentally, again, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), a world-famous entity mentioned many times in our equally famous blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since November 2018, produced a 13-minute documentary of Nova Scotia’s lobster fisheries in 1945. Behold, ye barnacle, Margaret Perry’s Trappers of the Sea…

Perry was a truly remarkable individual, by the way. That photographer / projectionist became an NFB documentary film director in 1942 and, in 1945, head of the Nova Scotia Film Bureau. Well, actually, Perry was the sole employee of said bureau. Even so, she directed more than 50 documentary films between 1945 and 1969.

But back to Magee, a gentleman we have been seriously neglecting.

As he grew older, Magee never lost his interest in education. Indeed, around 1945-46, he rekindled his old friendship with the aforementioned Peacock, by then New Brunswick’s Chief Superintendent of Education. The two men began to plan for a new school designed to meet the need of rural area students, both academic and vocational, a school which would be built in Port Elgin.

Magee donated the money needed to build a vast auditorium / gymnasium. He also had charge of financing the sum of money required as Port Elgin’s share of the project, which was half of the $ 500 000 the school would cost.

Magee’s spouse, Myrtle Rena Magee, born McLeod, donated the land on which the school was built.

The Regional Memorial School opened its doors in September 1948.

Port Elgin’s share of that project was of course worth… Yes, approximately $ 3 800 000 in 2024 currency. Your mathematical skills are not as bad as you think, my reading friend. To quote / paraphrase Morticia A. Addams, born Frump, in the 1991 American supernatural black comedy motion picture The Addams Family, do not torture yourself, that is my job.

Magee’s many contributions to education had been recognised in May 1947, when the University of New Brunswick conferred him an honourary doctoral degree.

At some point in the late 1940s or early 1950s, as he sat in the Senate of that university, Magee began to campaign for the creation of a degree course in business administration. At best, he was faced with indifference, at worst, with opposition. Unwilling to back down from what he though was a reasonable idea, Magee sweetened his proposal with the offer of a substantial donation.

As was to be expected, money speaking louder then reason, sorry, sorry, in October 1952, the University of New Brunswick announced that it would soon offer a degree course in business administration, an offering made possible by a gift, Magee’s donation of course, totalling $ 25 000, and by the financial support of various New Brunswick firms. As time went by, a 4-year business administration curriculum was created.

By the way, Magee’s donation corresponded to approximately $ 280 000 in 2024 currency.

Fred Magee left this world in May 1953. He was almost 78 years old.

Unlike many individuals who were / are (and will continue to be?) all hat and no cattle, Magee put his money where his mouth was.

Magee bequeathed the bulk of his estate, in other words close to $ 1 000 000, to the University of New Brunswick. That pile of dough, equivalent to approximately $ 11 500 000 in 2024 currency, was to be turned into a Fred Magee endowment fund which would provide loans to students in need.

Mind you, Magee also bequeathed $ 10 000 in company stock to Mount Allison University of Sackville, New Brunswick, and to the Université Saint-Joseph of Memramcook, New Brunswick, the first and only, at the time, francophone university in the Atlantic provinces.

Another $ 5 000 in company stock went to the Providence Saint-Joseph, a retirement home in the lobster capital of the world, the Acadian town of Shediac, New Brunswick.

It is worth noting that, contrary to many anglophone New Brunswick politicians of his generation, Magee was not unsympathetic to the francophone minority of the province and its wish to have its children and teenagers educated in French.

And yes, your calculations are correct, my punctilious reading friend, those $ 10 000 and $ 5 000 corresponded to approximately $ 115 000 and $ 57 500 in 2024 currency.

And that was not all. In May 1953, a snippet appeared in some Canadian newspapers to the effect that, “For each year of continuous employment, employees of the late Dr. Fred Magee will receive a half share of preferred stock in his three lobster canning plants. A share is worth $100.” That sum was worth approximately $ 1 150 in 2024 currency.

The staff of Magee’s residence on Port Elgin also received stock, presumably a half share of preferred stock for each year of continuous employment.

Incidentally, the canneries in question were located in Port Elgin, Pictou, as well as Caribou, Nova Scotia.

And you have a question, my reading friend? Did Magee’s Mephisto brand lobster survive its creator?

Well, it did. For a while. You see, as the years flew by, new methods of refrigeration and travel by air cut more and into the canned lobster market. I mean, why buy lobster meat in cans when it was possible to have a live New Brunswick lobster flown to Montréal, Québec, or Toronto, Ontario, the day it was caught, so that it could be delivered to some posh establishment?

Indeed, a gradual switch to the shipment of live lobsters might have begun no later than 1938.

The most recent piece of evidence that yours truly came across regarding the sale of Mephisto brand lobster was a mention in an advertisement published in a late July 1962 edition of L’Événement journal, a long gone and all but forgotten daily newspaper published in Québec, Québec.

Interestingly, the advertisement in question came from Alimentation Service et Prix, a voluntary chain of (independent?) Québec, yes, the city, grocery stores operated by a wholesaler from Québec, yes, again, the city, namely the Société provinciale des épiciers Incorporée.

That same wholesaler was later absorbed by one of the firms which gave birth, in June 1970, to a well-known grocery retailer, Provigo Incorporée of Montréal, a division of Loblaws Companies Limited of Brampton, Ontario, since December 1998.

Sadly enough, I was unable to uncover the precise date of the disappearance of the firm at the heart of this issue of our unforgettable blog / bulletin / thingee. It is in fact possible that Fred Magee was sold before the passing of its founder.

Incidentally, Homarus americanus has managed to hang on. Indeed, Canadian fishermen caught 98 050 or so metric tonnes (96 525 or so imperial tons / 108 100 American tons) of lobster in 2022. Said catch, which was 3.75 times (!) bigger than that of 1913-14, was worth 1.78 or so billion dollars, a sum which corresponded to 1.89 or so billion dollars in 2024 currency. I kid you not. By comparison, the 1912 catch was worth 135 million dollars in 2024 currency.

By the way, approximately 15.8 % of that 2022 fortune was landed by New Brunswick fishermen.

And yes, Homarus americanus is Canada’s most valuable sea creature export.

And so our story ends. For now.

This writer wishes to thank the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

Being the lazy bum that I am, yours truly will be taking tomorrow, in other words Canada Day, off.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)