“Canned it is most excellent, being splendid for pies” – The crawling and flowering saga of a slight horticultural mystery of the early 20th century, the loganberry, part 1

Are you one of those people who likes to pick her or his own fruity delicacies, be they blueberries, raspberries or strawberries? Yours truly must admit that I was not too thrilled when my father required my services on at least one occasion, more / way more than 50 years ago, to pick up such delicacies on a farm near Sherbrooke, Québec, my homecity.

Mind you, I was no more thrilled to go on some shrubby patch of land relatively near that city with my parents and the family of a lady cousin of my mom to pick up wild blueberries. You see, a portable radio was part of the equipment used during such operations. The idea being that the loud music emanating from it and the equally loud conversations of everyone would warn the Ursus americanus from those parts that a small troop of humans was in the vicinity, in the act of stealing their food. Children were duly warned not to wander too far, just in case.

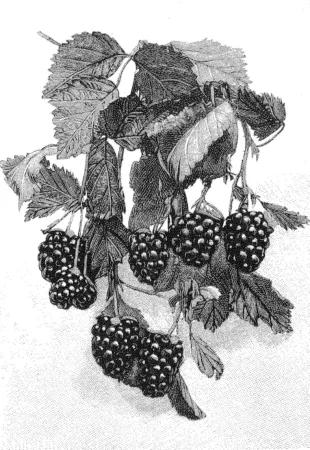

Anyway, as yours truly pored through the pages of La Nature, a very fine French scientific popularisation weekly magazine launched in June 1873 by the French meteorologist / editor / chemist / author / aeronaut Gaston Tissandier, I stumbled across an illustrated article on the loganberry and… Yes, yes, an aeronaut / balloonist.

Indeed, I have a feeling Tissandier was one of the people mentioned in the 1995 international and bilingual travelling exhibition The Balloon Age created by what was then the National Aviation Museum of Ottawa, Ontario, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in close cooperation with the Stewart Museum of Montréal, Québec, which no longer exists, and the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace of Paris, France.

Incidentally, yours truly was the researcher for that exhibition. Would you believe that I spent 2 or 3 weeks in Paris, all expenses paid, looking for illustrations and objects at said Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, courtesy of the Canada-France Agreement component of the Museums Assistance Program (MAP) of the Department of Canadian Heritage, I think?

Mind you, I also contributed to the English and French versions of The Balloon Age and Au temps des ballons, a pair of CD-ROMs created around that exhibition. There is a story about the creation of those CD-ROMs that I might tell some day. Perhaps.

Ahhh, the good old days. When I had hair. Sorry, sorry.

Incidentally,

- given that the 500th anniversary of the arrival in North America of the French expedition led by Jacques Cartier will undoubtedly be celebrated in 2034,

- given that the 250th anniversary of the first piloted balloon flights, in France, will undoubtedly be celebrated in 2033,

- given that the 125th anniversary of numerous significant aeronautical events, events which often occurred in France, but also in Canada, will undoubtedly be commemorated in 2033-34,

some museum people in Ottawa may wish to consider the possibility of developing international (travelling?) exhibitions with one or more Canadian and French museal institutions able to take advantage of the moolah present in the coffers of the aforementioned Canada-France Agreement component of the MAP. Just sayin’.

There might be all expense paid trips in the offing for them, after all. (Hello, EG, EP and VW!)

And yes, that was a loooong sentence, and back to our loganberry.

Incidentally, I am told that the French name of the dark purplish / dusty maroon red aggregate fruit produced by that plant is mûroise / ronce-framboise. The plant which produces it is the mûre de Logan. Somehow, I doubt that francophones use the term mûroise when referring to that aggregate fruit, but I digress, and…

Yes, yes, an aggregate fruit / etaerio. Technically speaking (typing?), loganberries are not berries at all, and neither are raspberries and blackberries by the way. This being said (typed?), blueberries and gooseberries are true berries. Tomatoes too, by the way, as well as eggplants and avocados. Strawberries, in turn, are accessory fruits / false fruits / pseudofruits / spurious fruits, but back to our topic, and…

You are puzzled, are you not, my reading friend? Well, an accessory fruit is a fruit whose flesh does not develop from the ovaries of a plant’s flowers. In turn, an aggregate fruit is a fruit which develops from the merger of several / many distinct ovaries contained in a single flower. End of digression.

Incidentally, if I may paraphrase / quote the Anglo-Irish novelist / Anglican cleric Laurence Sterne, author of the 9-volume novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, published between 1759 and 1767, digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine; – they are the life, the soul of reading; – take them out of this blog / bulletin / thingee for instance, – you might as well take the blog / bulletin / thingee along with them.

For example, did you know that the author of the article in which yours truly found the drawing at the beginning of this article, yes, the one in a July 1904 issue of La Nature, the French professor / journalist / horticulturist / editor / author Albert Maumené, was, among other things, a populariser of photography on fruits. Yes, yes, you read it right. Photography on fruits.

That scientific and artistic recreation of the late 19th and early 20th centuries consisted in applying a cover cut from paper or the negative of a photograph on the skin on an unripe fruit whose skin had been hidden from the sun with a bag very early on, apples being particularly good subjects, and leave that fruit in peace, exposed to the sun, during 20 to 30 days, until it was ripe. The cover or negative had to be applied the right way of course, to make sure that any writing present would be legible.

And here is an example of photography on fruits.

A portrait of the Tsar of Russia, Nikolaï II, born Nikolaï Aleksandrovich of house Romanov, on an apple. Albert Maumené, “Comment Photographier sur Fruits.” Jardins et Basses-Cours, 20 September 1909, 373.

Mind you, Maumené also wrote the first French language book on the Japanese art of bonsai. And bonsai is an art. I discovered I did not have a green thumb when the miniature tree I bought in the late 1980s kicked the proverbial bucket within weeks, if not days. Poor thing, but back to our topic.

As I came across the aforementioned article, yes, again, the one in a July 1904 issue of La Nature, it occurred to me that it would make a tasty addition to the list of topics of our succulent blog / bulletin / thingee. Shall we begin our quest for the loganberry?

One could rightfully argue that the story of that delectable aggregate fruit began in December 1841 with the birth, in Rockville, Indiana, of James Harvey Logan.

A district attorney (1870s) and superior court judge (1880s and 1890s) in Santa Cruz, California, a bank manager also, Logan was a keen amateur botanist / plant breeder / horticulturalist. Mind you, he certainly loved preserves, pies, jams, cobblers, etc. Do we not all? Well, most humans do, I guess. Personally, yours truly tends to shy away from preserves, pies, jams, cobblers, etc. Too much sugar.

Somewhat unhappy with the size of existing blackberries, Logan collected every kind of blackberry and raspberry he could get his hands on and planted them in his garden.

Indeed, he attempted to produce a superior cultivar by crossing two types of blackberries, namely a cultivar of the Douglas berry / California blackberry / Pacific blackberry / trailing blackberry / California dewberry / Pacific dewberry known as the Aughinbaugh and an Eastern (?) United States blackberry cultivar known as… the Texas Early / Crandall. He happened to plant those plants next to examples of a raspberry cultivar known as the Red Antwerp and…

I recognise the hand of my honourable and ever curious reading friend poking through the ether. Is there a difference between a variety and a cultivar, you ask? A splendid question. To make a long story short, a rare occurrence in these parts I will admit, a variety is a naturally occurring variant of a species. A cultivar, on the other hand, is an artificially occurring variant of a species, a variant developed by people to express desirable traits, and…

You have another question, do you not? Was the Red Antwerp a Belgian cultivar of raspberries? Another splendid question. It can be answered with a firm yet polite no. Actually, it had little to do with Belgium, Anvers / Antwerpen / Antwerp being, as we both know, a Belgian city.

The name Red Antwerp was allegedly coined in the late 1780s or very early 1790s by an English plant nurseryman named Cornwall who noted that the red aggregate fruits produced by such plants were as large as those of a cultivar of yellow raspberries known as, you guessed it, the Yellow Antwerp.

The latter got this its name in an interesting manner. Some yet to be named plants were given to an English gentleman by the governor of Antwerp, Austrian Netherlands, today’s Belgium, Lieutenant General Petrus von Langlois, in 1783. Said gentleman, Henry Willoughby, offered those plants to his father. In turn, Lord Middleton, the 5th Baron Middleton actually, born… Henry Willoughby, gave the plants to his gardener who planted and nurtured them, but back to Logan.

And no, my overly romantic reading friend, those Willoughbys were not related to John Willoughby, the handsome young man who played a crucial role in the plot of Sense and Sensibility, an 1811 novel penned by the English novelist Jane Austen. How could that have been possible, my overly imaginative reading friend? John Willoughby was a fictional character. Now, where was I?

As these things were and still are wont to happen, pollen circulated in Logan’s garden. In the case which interests us today, pollen grains from the Red Antwerp raspberry cultivar fell on flowers of the Aughinbaugh blackberry cultivar, I think.

Unaware of what had taken place, Logan collected the seeds and planted them in 1881. You will remember that he was trying to create a new and improved blackberry.

In any event, the plants which resulted from that unplanned pollinisation were similar to, yet larger and more vigorous than the Aughinbaugh blackberry cultivar. They first fruited in 1883.

One or more of the plants gave birth to the loganberry or, as it was called early on, but not for long, the blaspberry.

One or more of the other plants gave birth to the Mammoth blackberry, or black loganberry, an aggregate fruit Logan was especially proud of. And yes, those Mammoth blackberries were quite simply ginormous, with a length of up to 65 or so millimetres (2.5 or so inches), or so claimed Logan. I kid you not, but I do digress.

Loganberries were of course smaller, with a length of up to 30 or so millimetres (1.25 or so inch).

A brief digression if I may. What Logan achieved by accident, in other words the creation of a successful raspberry-blackberry hybrid, had been tried on purpose by other individuals. One only needed to mention the French agronomist / botanist / physician / professor Louis Charles Trabut. The cultivars he came up with proved to be sterile, however.

Yours truly unfortunately does not know if one of those cultivars was the raspberry-gooseberry developed at the latest in 1905, in Algeria, and this in order to tolerate the climate of that French settler colony.

In the United States, the American botanist / horticulturist and pioneer in agricultural science Luther Burbank produced a successful cultivar in the early 1890s by crossing the Aughinbaugh blackberry cultivar with the Cuthbert raspberry cultivar, developed in England. The rights for this Humboldt berry, Burbank’s most successful creation, were soon sold to the American horticultural businessman / amateur ornithologist / politician John Lewis Childs, who promptly renamed it the Phenomenal berry, in 1894, and…

Yes, you are indeed correct, my reading friend, Childs apparently founded the first mail order seed catalog business in the United States.

And yes, there were undoubtedly other raspberry-blackberry hybrids developed around that time.

And yes, again, my green thumbed reading friend, one can certainly imagine that more or less successful raspberry-blackberry hybrids appeared spontaneously in one or more places. One only needs to mention the one found by Liberty Hyde Bailey, an American horticulturist / rural life reformer, in a dryish bog near Lansing, Michigan, no later than 1898.

Incidentally, Trabut was the individual who brought to the attention of the scientific community a citrus fruit hybrid between a willowleaf mandarin orange and a sweet orange, in other words a tangor. As we both know, that tangor produced the fruit known as the clementine. I love clementines. How about you?

While yours truly does not know when commercial sales of loganberry plants began, I can state with some certainty that Logan granted exclusive sales rights to James Waters, a builder / carpenter / horticulturalist and founder of the Pajaro Valley Nursery of Watsonville, California, near Santa Cruz, and this no later than January 1895.

By the late 1910s, countless loganberry plants could be found in the milder areas of California, Oregon and Washington. Attempts to grow that plant in Southern, Northern, Eastern and Central states of the United States did not prove all that successful, however.

It should be noted that the loganberry began to appear in Europe, in this case England, around 1897.

In 1900, a well-known pomological society based in the Netherlands, the Koninklijke Vereniging voor Boskoopse Culturen, awarded one of its first-class certificates of merit to the loganberry. In England, the Fruit Committee of the Royal Horticultural Society granted an award of merit to, you guessed it, the loganberry in 1903.

In the United States, large quantities of loganberries were canned, dried, preserved or turned into jams, jellies, soda fountain syrups or wines. All of this transformation work was due to the fact that the typical loganberry was a tad too acidic / tart to be consumed fresh in large quantities.

A typical advertisement for Waukesha Pure Food Company’s Jiffy-Jell fruit flavoured gelatin dessert which prominently featured loganberries in all their glory. Anon., “Waukesha Pure Food Company.” The York Dispatch, 17 September 1918, 3.

Would you believe that packages of loganberry-flavoured Jiffy-Jell, the second fruit flavoured gelatin dessert marketed in the United States, if not North America, hit the shelves no later than September 1918?

Produced by an American firm, Waukesha Pure Food Company, from early 1916 onward, I think, Jiffy-Jell quickly became very popular. Sadly enough, that popularity was short-lived.

You see, the various fruit essences used in the various mixes were preserved with alcohol. Yes, yes, alcohol. I kid you not. A scarce commodity during the First World War, especially after the United States entered the fray, in April 1917, alcohol became public enemy number 1 with the onset of prohibition in the United States, in January 1920.

Waukesha Pure Food attempted to replace the alcohol in its production process with another product. It failed. In 1921, the firm’s management sold its factory and the production rights of Jiffy-Jell to another American firm. Incidentally, Genesee Pure Food Company was already producing a fruit flavoured gelatin dessert and you know which one, of course. Yes, that one, the first fruit flavoured gelatin dessert marketed in the United States, if not North America.

In 1923, Genesee Pure Food became Jell-O Company, the proud maker of chocolate Jell-O, among other varieties, and…

Yes, yes, chocolate Jell-O. Introduced in 1927, that version of the world-famous gelatin dessert was yanked off the shelves in… 1927. I wonder why, but back to our fruity friend, the loganberry.

The drying of loganberries might, I repeat might, have played an important role in the success of that aggregate fruit from 1908 or so onward. Let me explain. Ripe loganberries were proving too fragile to stand much travelling and early attempts at canning proved unsuccessful because canners used plain tin rather than its enameled and acidity proof cousin. Faced with local markets glutted with loganberries, many producers began to tear up their fields.

In desperation, a couple of producers turned to the drying tooling used in conjunction with prunes. Their dried loganberries proved popular, especially in the Eastern United States.

Realising that the dried loganberry market could soon reach its saturation point, some producers experimented with juice production. The new product met with near instant approval.

A typical advertisement for Northwest Fruit Products Company’s Loju loganberry juice. Anon., “Henry May & Company Limited.” Honolulu Star Bulletin, 16 March 1916, 8.

And so it was that, from 1915 onward, one could buy a non-alcoholic beverage made from loganberries, Loju, bottled by an American firm, Northwest Fruit Products Company.

Oregon Fruit Juice Company, an American firm which became Pheasant Fruit Juice Company around March 1916, began to produce a similar product, Phez, during that same year. Yes, 1916. The two firms merged around February 1918, to form Pheasant Northwest Fruit Products Company, later known as Phez Company. Both Loju and Phez seemingly remained on sale, at least for a while.

As was to be expected, there were many who thought (hoped?) that loganberry beverages would gain in popularity given the onset of prohibition in the United States. They were correct, but only to a point. A fairly small point in fact.

And so ends the first part of this article on the loganberry.

You will be back for more of that tasty treat, will you not, my reading friend?

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)