“Is This Prophetic of Future?”: University of Saskatchewan professor Robert Dawson MacLaurin and the billowing saga of straw gas, part 1

How would you feel about the idea of using a definition to launch this issue of our mind-blowing blog / bulletin / thingee? […] Thank you. And apologies for the tardy appearance of this text online. I overslept.

By the way, Visalia is a city in the San Joaquin valley of California, located half way between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

According to a 2023 document of the United States Energy Information Administration, an agency of the United States Department of Energy, and I quote,

Biofuels are a set of renewable fuels made from biomass feedstocks such as corn, vegetable oils, animal fat and other similar. Biofuels includes ethanol, biodiesel, biojetfuel and renewable diesel.

Even though the examples given above are all liquid biofuels, the definition itself does not seem to exclude gaseous or solid fuels.

As you may well image, there are more than one type of biofuels. First generation biofuels, for example, are derived from existing edible row crops like sugarcane, soy and corn / maize, which was / is not necessarily a good idea in a world where countless people go to bed hungry every night. By comparison, second generation biofuels are derived from cellulosic biomass like organic waste, agricultural residues and perennial grasses. Third generation biofuels, on the other hand, are derived from microalgae. Fourth generation biofuels, finally, at least for now, are derived from bioengineered organisms like fungi, bacteria and microalgae.

Even though the use of the term generation suggests the idea of a process which unfolds over time, the fact is that there is no reason why a second generation biofuel has to be developed after a first generation biofuel.

Have you, for example, ever heard of straw gas? Yes, my slightly cheeky reading friend, before you saw the title of this article. Sigh… You had not? Well, neither had I.

One could argue that our story began in February 1879 with the birth of Robert Dawson MacLaurin in Vankleek Hill, Ontario, a town located… halfway between Ottawa, Ontario, and Montréal, Québec, or so I thought, until I discovered that the origin story of this story began elsewhere, in Wales actually. Still, given Dawson’s key role in our story, let us proceed along that path anyway, shall we?

A brilliant young man, MacLaurin earned a Bachelor’s Degree from McMaster University (Hello, EG!), then located in Toronto, Ontario, a Master’s Degree from that same institution, in 1903, and a doctorate from Harvard University, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1906.

MacLaurin’s work on physiological chemistry at that latter institution proved so impressive that the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, in New York City, New York, made him a research fellow.

And yes, that biomedical research institute, the first of its kind in the United States, had been founded in June 1901 by none other than John Davison Rockefeller, Senior, the richest Homo sapiens on planet Earth and a world famous (infamous?) American robber baron.

In 1907, MacLaurin began to work at one of the experimental stations of the Massachusetts Agricultural College, in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Robert Dawson MacLaurin, circa 1910-12. University of Saskatchewan.

MacLaurin joined the staff of the University of Saskatchewan, in… Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, around August 1910, as professor of Chemistry. Indeed, he was the founding head of the university’s newly formed Department of Chemistry.

As the weeks into months, and the months into years, Maclaurin became one of best known faculty members of the institution. Indeed, again, he arguably became one of the most audible voices on the need and usefulness of research in Saskatchewan. MacLaurin’s career seemed to be well on track. That career took a new turn during the First World War, however.

To understand how that turn came about, a brief journey to Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, will prove necessary.

George H. Harrison with one of his straw gas production devices, Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, circa 1917. Anon., “Plant for Farms Makes Gas From Straw.” Popular Mechanics, August 1918, 176.

You see, news reports began to appear in newspapers of Western Canada in September 1916 about a small straw gas production device developed by George H. Harrison, a Welsh Canadian marine engineer and mechanic living in Moose Jaw who happened to be the manager of Saskatchewan Bridge and Iron Company Limited and the founder of the Dominion By-Product and Research Society, and…

No, my over imaginative reading friend, Harrison was probably not related to another George Harrison, an English songwriter / singer / musician / lead guitarist of an iconic English rock band, the Beatles.

This being said (typed?), Harrison’s assistant manager was seemingly Ernest Gaskell Sterndale Bennett, an English Canadian amateur theatre actor / mechanical engineer who would go on to become a renowned actor / adjudicator / consultant / director / teacher active in the field of Canadian theatre for more than half a century, but back to our story.

Said straw gas production device, developed in 1915-16, was said to be so simple that any Western Canadian farming family would soon be able to turn straw, a much-despised waste product until then, into a gas it would be able to use to cook its food, heat and light its home, and run its various stationary farm engines.

And yes, the gas produced was said to be at least as good as coal gas or natural gas, and… Err, yes, coal gas was / is a combustible gas made from coal.

Harrison was so confident in the success of his invention that he had applied for patents not only in Canada and the United States, but also in Argentina and the Russian Empire.

Wilbur Williams Andrews, one of the partners in a respected analytical and consulting chemistry bureau of Regina, Saskatchewan, Andrews and Cruickshank, had been involved in the development of Harrison’s idea almost from the beginning. Indeed, a miniature straw gas production device had been producing gas in the bureau’s laboratory for some time when newspapers began to publish articles.

You may be interested, or not, to read that Harrison was not the first Homo sapiens to come up with the idea of using straw to produce gas. Nay. A Canadian resident of Cleveland, Ohio, by the name of James Russell Coutts had come up with that very idea during a visit to or stay in a farm, somewhere in Western Canada, around 1904.

Yours truly has a feeling the Coutts in question had been the pastor of a protestant church in Toronto, a few years before. Indeed, he had apparently been a resident of Kemptville, Ontario, who had graduated from… McMaster University, with a degree in theology. Small world, is it not?

Intrigued by the burning straw he had seen on at least one occasion, Coutts mentioned his idea of using straw to produce gas to a professor at… McMaster University. Encouraged by that person, he conducted experiments. Some Toronto businessmen were allegedly sufficiently intrigued by Coutts’s idea to provide him with the moolah needed to scour libraries in the United Kingdom, the German Empire and France.

Mind you, while in England, he also talked with several eminent chemists. Once back in North America, Coutts paid a visit to several equally eminent American chemists.

Coutts’ idea was developed in parallel with patent applications not only in Canada and the United States, but also, it was claimed, in many other countries (Argentina, Australia, Austria-Hungary, British Raj, Egypt, Italy, Mexico, Russian Empire and Spain).

And yes, the British Raj primarily enclosed countries known today as Pakistan, Myanmar, India and Bangladesh.

Coutts and his partners formed a firm, International Heating & Lighting Company of Cleveland, seemingly headed by said Coutts, and set up an experimental straw gas production device in or near Cleveland.

In early 1907, a well connected Canadian American clergyman / newspaper editor / preacher, Charles Aubrey Eaton, applied for and received a franchise from the municipal council of Beatrice, Nebraska, to set up a gas plant which would use straw, corn stalks and corn cobs as fuel. That plant went into operation in July 1907. It might well have been the first facility of its type in the world. The gas it produced was seemingly used to light buildings in the city.

Would you believe that Eaton was the preacher at a protestant church in… Cleveland attended by, among other local luminaries, the aforementioned Rockefeller? Indeed, (judiciously planted?) rumours circulated to the effect that this robber baron had invested an infinitesimal fraction of his own (nefariously acquired?) dough in International Heating & Lighting. Small world, is it not?

Would you also believe that International Heating & Lighting supervised the construction of a gas plant in Brandon, Manitoba? That coal-fired, yes, yes, coal-fired facility became operational in December 1909.

Other (coal-fired?) construction projects fell through, however, in Alberta (Edmonton), Manitoba (Portage la Prairie), Ontario (Fort William / Port Arthur) and Saskatchewan (Moose Jaw, yes, yes, Moose Jaw and Regina). In at least one case, Edmonton if you must know, discussions had gone on for more than 4 and a half years.

And no, yours truly cannot state with certainty that Beatrice’s gas plant was the only one of its type in the United States.

A brief digression if I may. Eaton’s nephew, Cyrus Stephen Eaton, was a well known and influential / controversial Canadian-American investment banker / businessman / philanthropist who funded and helped organise a conference where scientists from 10 countries looked at the dangers posed by nuclear weapons. That conference was held in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, in July 1957. (Hello, EP!) And yes, that conference was the very first of a series of Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs which continues to this day.

Another digression if I may and please note that this one is quite disturbing.

If one was to believe a news report, the aforementioned Coutts was sued by a young lady from New York City. Theresa M. Almer had agreed to marry him, until her discovery that the cad already had a spouse, that is. She asked for US $ 50 000 in damages in December 1909, a sum which corresponds to approximately 2 300 000 $ in 2023 Canadian currency. No additional information on that civil suit could be found but it looked as if Coutts moved (skedaddled?) to England around that time.

And yes, Cyrus Stephen Eaton then became president of International Heating & Lighting. That firm, by the way, seemingly disappeared from view around 1911-12, which brings us back to the aforementioned Harrison and his straw gas dreams.

Saskatchewan Straw Gas Company Limited of Moose Jaw came into existence in January 1917.

That same month, farmers who attended the 1917 meeting of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association, in Moose Jaw, saw a demonstration model of the straw gas production device developed by Harrison. Some of them were intrigued. Others were amused.

Even though he did not want to favour Harrison’s invention, the founding dean of the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Saskatchewan, William John Rutherford, nonetheless stated that, if the device could do what it was supposed to do, it would be “one of the most wonderful discoveries of the age.”

From the looks of it, the original version of the domestic version of the straw gas production device had a chamber-oven the size of an office desk. That chamber-oven could absorb close to 35 kilogrammes (75 pounds) of straw, which would result in the production of 14 or so cubic metres (500 or so cubic feet) of gas in 30 or so minutes. The device seemingly included a scrubber, to clean the gas and remove impurities, and a gasometer, to measure and store the gas.

While straw or some other fuel to heat the straw could certainly be used, using some straw gas for that purpose also made a lot of sense.

The fact that the production of straw gas did not require temperatures as high as those required to produce coal gas meant that less fuel was needed, and that production costs were not as high, but I digress.

According to press reports, two loads of straw would produce enough gas to produce the lighting, heating and cooking energy required by a 10-room house over a period of 24 hours, and this at a temperature of -40° Celsius (-40°Fahrenheit). It went without saying (typing?) that a lot less straw would be required in summertime.

Interestingly, the device included a chamber which stored the byproducts of the gas producing process. One such byproduct, coal tar, would be of value to firms involved in the production of synthetic dyes known as aniline dyes / coal tar dyes.

According to Harrison, his domestic straw gas production device would not cost more than the tidy sum of $ 500, an amount which corresponds to $ 9 900 or so in 2023 currency. Mind you, that sum was said within the reach of a sizeable majority of Saskatchewan farmers.

Given the amount of straw produced in Saskatchewan, enough gas could theoretically be processed to produce the lighting, heating and cooking energy required annually by 43 750 or so family homes, an impressive figure when compared to the number of farms in that province in 1921, that is 119 450 or so. The word theoretically was important here given that a great deal of straw was used by farmers for animal feeding and bedding purposes.

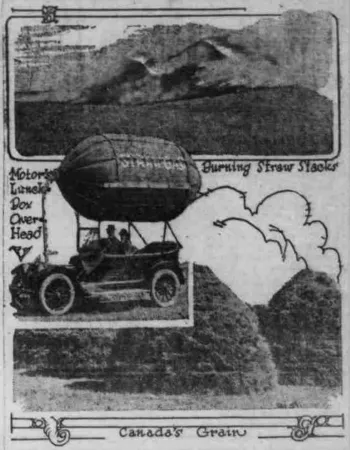

And yes, my attentive reading friend, you are quite correct in reminding me that straw gas could also be used to power various stationary farm engines. Better yet, it could be used to power automobiles. Yes, yes, automobiles, or even trains, or so claimed Harrison.

Let us not forget that a tonne or so of straw could produce a volume of gas whose energy was equivalent to that of more than 155 litres of gasoline. The non metric figures would be 35 or so imperial gallons of gasoline per imperial ton of straw and more 37 American gallons per American ton. A farmer’s Ford Model T could go pretty far with that much go-go juice.

Incidentally, gasoline cost 8.8 or so cents per litre (40 or so cents per imperial gallon / 33.3 or so cents per American gallon) in Saskatchewan, in 1917, a sum which corresponds to $ 1.75 or so per litre ($ 7.95 or so per imperial gallon / $ 6.60 or so per American gallon) in 2023 currency.

Incidentally, again, how much are you paying for your go-go juice these days, my driving reading friend?

And no, yours truly does not think that an automobile seen on a 2023 road would run for long, if at all, on the gasoline available in 1917, gasoline whose rating did not exceed 65 octane and might have been as low as 40 octane (Yikes!), but back to our main line of thought.

By May 1917, more than 5 000 requests for information had been received by Harrison and / or Saskatchewan Straw Gas, and this from every region of Canada where straw was produced in some quantity.

Better yet, the secretary for of the Prairie provinces branch of the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, was quoted as stating that “The possibilities of the system are enormous.” Harrison’s device, stated George E. Carpenter, should be tested in every region of the country to assess its commercial potential.

Would you believe that Harrison and / or his firm were encouraging the federal government to undertake production of domestic straw gas production devices and regulate the price of straw?

As you may well imagine, MacLaurin was aware of what was being done by Harrison. He had actually seen his straw gas production device in March 1917. MacLaurin was very interested, so interested in fact that, in April, rumours circulated to the effect that he might leave his post at the University of Saskatchewan to join the upper echelons of Saskatchewan Straw Gas in order to manage the production of the straw gas production devices.

Even though MacLaurin did not, in the end, leave his teaching position, he did invest some of his own dough in the Dominion By-Product and Research Society.

Mind you, MacLaurin’s interest might have been stimulated by the fact that the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association was eager to see its members acquire said straw gas production devices in large numbers. The association seemed to be of the opinion that those devices could revolutionise life in rural Saskatchewan. On top of that, their use could result in significant annual savings, savings which could be used for a variety of purposes.

As enthusiastic as promoters of the straw gas production project were, the May 1917 fire which destroyed the building of the aforementioned Saskatchewan Bridge and Iron where that gas was being made came as a nasty surprise. Even so, it seemingly did not put much of a damper on things.

Indeed, the University of Saskatchewan provided some money to someone at some point to see if the straw gas production project had legs.

MacLaurin, for one, remained deeply enthusiastic.

How enthusiastic was he, you ask, my reading friend? Come back in a few days and you might find out.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)