A tale of air, water, and fire: A peek at the aeronautical activities of Hoffar Motor Boat Company of Vancouver, British Columbia, 1915-27, part 3

Again, greetings and salutations, my reading friend. You will of course remember how the first part of this article ended. Something about the beginning of a new phase in the aeronautical history of Hoffar Motor Boat Company of Vancouver, British Columbia. Well, the hyper long digression also known as Part 2 of this article is finally behind us, which means that we finally have the means, motive and opportunity to jump into the fray. Are you ready? Wunderbar!

Our story began with the Minister of Lands of British Columbia, or else someone who had his ear. In any event, at some point during the spring of 1918, Thomas Dufferin “Duff” Pattullo began to think that aeroplanes could be of use in defending the province’s vast and valuable forests against forest fires.

You see, the wood of the large numbers of large and very large spruce trees found in those forests was a strategic / critical material, to use an anachronistic expression. In other words, spruce trees were of vital importance to the aeroplane industries of the Allied countries. Their wood was one of the best readily available materials to make the long spars of the wings of the aeroplanes flown during the First World War.

Forest fires threatened that strategic / critical resource and the sad truth was that the summer of 1917 had proven itself to one of the worst of the decade, and this in many regions of British Columbia. Any form of assistance would therefore be most welcome. Why not aeroplanes, thought Pattullo?

Yours truly wonders if that minister came to that conclusion as a result of the positive responses of the membership of the province’s Fire Protection Committee to a suggestion made in late March 1918 by the General Manager of a logging firm, Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing Company Limited of Chemainus, British Columbia. Edmund James Palmer’s reasoning went as follows.

Given the speed at which aeronautical technology was progressing, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) of the Royal Navy undoubtedly had a lot perfectly usable yet obsolete aeroplanes. The government of British Columbia should ask the federal government to ask the British government if several aeroplanes, presumably seaplanes actually, could be secured at a nominal cost.

The fact that a certain number of aviators born in British Columbia would be sent home in 1918 as a result of injuries or diseases suffered overseas could prove very useful in that regard. Although no longer able to fight, some of them might be prevailed upon to patrol the forests of their home on native land, if yours truly may quote a few words of the version of the national anthem Oh Canada sung in February 2023 by a Canadian songwriter / singer / actor, Jully Black, born Jullyann Inderia Gordon Black, mentioned in May and June 2023 issues of our dazzling and astounding blog / bulletin / thingee.

It went without saying that, after the victorious end of the First World War hoped by one all, more aviators would return home to British Columbia, thus adding to the roster of potential aerial forest fire spotters. And yes, my astute reading friend, some / many of the aviators who would return to British Columbia during and after the conflict had worked for the Forest Branch of the Department of Lands before their enrolment, but back to our story.

As favourable as they were to Palmer’s suggestion, the members of the Fire Protection Committee were seemingly of the opinion that it could hardly be realised in 1918. Several / many industry insiders disagreed. Pattullo was obviously one of them.

You see, in mid July 1918, news reports appeared which indicated that the Department of Lands was about to enter into negotiations which would lead to the leasing of a seaplane to see if flying machines could be of use to control forest fires. If the 1918 experiment, scheduled to take place before the middle of August, proved successful, several seaplanes could (would?) be put into service in 1919.

To answer the question quickly forming in your noggin, the department was interested in seaplanes because there was not one real aerodrome in the interior or along the coast of British Columbia where a landplane could operate from. There were, however, a great many lakes and arms / bays / coves / inlets from which a flying boat or floatplane could operate from.

Would you believe that Pattullo seemed quite interested in going aloft at least once?

You will undoubtedly be pleased to hear (read?) that the Department of Lands and Hoffar Motor Boat signed a contract in late July 1918, according to which the latter agreed to build a 2-seat single engine flying boat that the former would lease for a year in order to conduct a series of experimental forest patrol flights. If all went well, the department might purchase that machine at a later date.

How about the obsolete military machines mentioned above, you ask, my reading friend? Were they still part of the plan? Err, from the looks of it, no. You see, even though it briefly considered the possibility of leasing 1 or 2 such machines, the department had come to the conclusion that a flying boat designed from the start as a forest patrol machine would be a better fit.

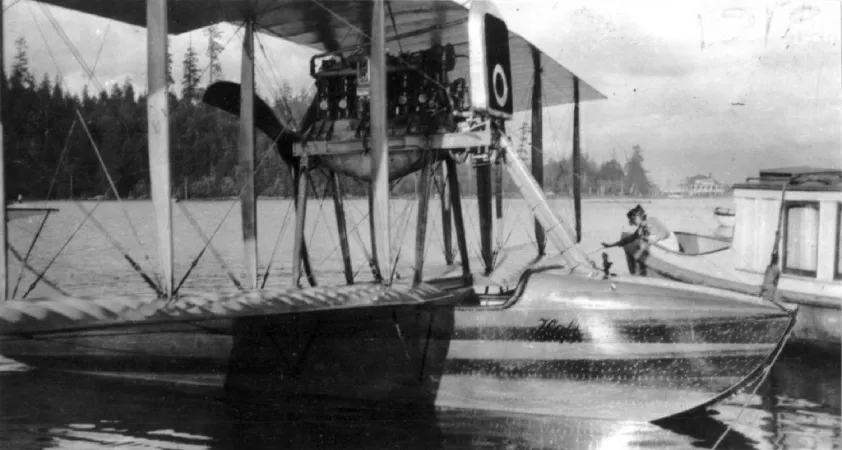

The staff of Hoffar Motor Boat completed the $ 8 000 biplane forest patrol flying boat, later known as the Hoffar H-2, shortly after mid August 1918, a month or so later than the date mentioned earlier by the Deputy Minister of Lands, George Ratcliffe Naden. Incidentally, that $ 8 000 corresponds to more than $ 140 000 in 2023 currency.

If truth be told, yours truly does not know when the designation H-2 made its appearance, or the name of the person who introduced it.

The pilot of the new machine would be an individual born in British Columbia, Captain William Herbert Mackenzie of Victoria, British Columbia, a gentleman who had served in the RNAS and its successor, the Royal Air Force (RAF). Before going on furlough to Canada, that experienced seaplane pilot was seemingly involved in some sort of experimental work, possibly, I repeat possibly, at the Seaplane Experimental Station of the RAF, previously RNAS Felixstowe, in England.

Mackenzie was to fly the Hoffar flying boat until he was satisfied with its performance, reliability, safety, etc. Then, and only then, would an experience military pilot who had worked for the Forest Branch of the Department of Lands before his enrolment be allowed to fly Canada’s first forest patrol aeroplane.

Pattullo seemingly planned to hold some sort of handover ceremony near Victoria, at Sooke Lake.

In any event, the Hoffar flying boat seemingly flew for the first time on 25 August 1918. James Blaine “Jim / Jimmie” Hoffar was at the controls for the first and second flights. Everything seemed to be in order. Mackenzie was at the controls for the third flight. Although generally pleased, he thought that the controls of the flying boat were a tad too sensitive. There were also some minor structural defects. Even so, Peter Zemro Caverhill, the Assistant Chief Forester of British Columbia, took at least partial possession of the aeroplane that very day. And yes, thousands upon thousands of Vancouverites witnessed the flights made by Hoffar and Mackenzie.

Mind you, it looks as if another Victoria aviator, a certain Captain Grant, was involved in the testing.

Within a day or three, the staff of Hoffar Motor Boat effected some minor alterations to the flying boat in order to increase its stability and remedy its structural defects.

Mackenzie flew the aeroplane on 29 August in order to complete the official trials required by the Department of Lands. All in all, he was very pleased. And yes, again, thousands upon thousands of Vancouverites witnessed the flight made by Mackenzie. Would you believe that, on that fine day, that pilot made no less than 4 flights? Or that a passenger was with him on each occasion? Incidentally, one of those passengers was Caverhill.

From that point on, Mackenzie would not be involved in the forest patrol project, however. You see, he had just packed his suitcases before returning to Europe in order to return to combat. The Hoffar flying boat would need a new pilot. And soon.

And yes, my astute reading friend, it looks as if Grant would no longer be involved in the forest patrol project either.

The aforementioned Naden… Yes, the Deputy Minister of Lands. The aforementioned Naden informed the press that the Hoffar flying boat, if temporarily taken over, would be used to patrol a 325 or so kilometre (200 or so miles) long strip of coastline north of Vancouver. The crew of the aeroplane during that 2 month long operational testing period would consist of 2 RAF aviators who had been staff members of the Forest Branch of the Department of Lands before their enrollment. If the flying boat proved satisfactory, the department would take it over permanently, which presumably meant that the aeroplane would be bought.

Contrary to what yours truly had thought, one of the aforementioned RAF aviators was not Lieutenant Victor A. Bishop, another British Columbia pilot home on leave, an armament instructor previously based in England who had been born there in fact. Even so, the Department of Lands was willing to pay that RNAS and RAF pilot $ 225 a month, a sum which corresponds to something like $ 4 000 in 2023 currency, to fly the aeroplane, if he could manage to get discharged from the RAF of course.

On 4 September, Bishop climbed aboard the Hoffar flying boat and took off. Everything was going swimmingly and then the engine misfired, then stopped, while the aeroplane was over Vancouver. Bishop tried to glide back to a body of water, English Bay it seemed, in order to make an emergency landing. Realising that he would not make it, Bishop tried to turn toward Coal Harbour and alight there. The flying boat stalled before that could happen. As thousands of Vancouverites, including Pattullo, watched in horror, it dove and went into a spin.

According to some, I repeat some, witnesses, Bishop left his seat and climbed on one of the lower wings of the flying boat, the left one I presume. That desperate attempt to stabilise the aeroplane, which probably did not take place at all, ended in failure. The aeroplane crashed into the roof of the house of an ear, eye and nose doctor by the name of James Collins Farish. The flying boat was damaged beyond repair.

And yes, that crash was / is the one portrayed in the illustration at the beginning of the first part of this article of our glorious blog / bulletin / thingee.

The wreckage of the Hoffar H-2 flying boat after its crash on the roof of the house of an ear, eye and nose doctor by the name of James Collins Farish, Vancouver, British Columbia. The gentleman wearing a uniform, on the left, might be Lieutenant Victor A. Bishop. The gentleman on the right might be Farish, or not. CASM, 2640.

Torn off from its mount, the engine of the flying boat ploughed through the roof of the house and ended up on the floor of the upstairs bathroom. Bishop found himself there as well, dazed, confused and in pain. He had some serious bruises and cuts on his face and head. He had also wrenched his back. Still, Bishop was one lucky guy. He had not been crushed by the wayward engine and the flying boat had not caught fire.

As he staggered out of the upstairs bathroom, Bishop walked into the only occupant of the house at the time of the crash, the Farish family’s rather shocked housekeeper. Whether or not that lady applied some bandages on Bishop’s wounds was unclear. What was clear, however, was that Dr. Farish walked into Bishop as the latter staggered through the front door of the visibly banged up house. The rather shocked doctor helped Bishop into his automobile and drove him to a hospital.

According to another version of the story, Farish arrived home as Bishop was taken off the roof of his house. He patched up the aviator and accompanied him as an ambulance drove both men to a hospital.

As was to be expected, the scene of the accidents was soon packed with people and automobiles. Some / many people allegedly walked away with souvenirs. The mind boggles.

As was also to be expected, the Hoffar brothers soon arrived on the scene. They quickly took charge of the wreckage of their flying boat – and tried to shoo away potential souvenir hunters. The police officers and firemen who had rushed to the scene presumably assisted them in that regard.

Several, if not many children who were thus kept away from the aeroplane quickly turned their attention to the raspberry bushes on a neighbour’s property. A swarm of locusts could not have ravaged those any faster.

It should be noted that, in the hours and days which followed the accident, some people wondered if Bishop might have been attempting to perform aerobatics over the house of an aunt he was staying with when his engine gave out.

And no, it looks as if the suggestion made by a certain J. Robson of Vancouver, a denturologist perhaps, went nowhere. That gentleman had proposed that pieces of the wrecked flying boat be sold in order to defray the cost of Bishop’s stay in the hospital.

Ahh, the good old days before Canada’s publicly funded health care system came into existence, in 1966, thanks to the Medical Care Act – and Premier of Saskatchewan (1944-61) Thomas Clement “Tommy” Douglas. Sorry, I digress.

Farish was understandably relieved to learn that the Department of Lands would defray the expense of repairs to his house.

Would you believe that an Australian quarterly magazine, Australian Forestry Journal, mentioned the trials of the H-2? I kid you not, but I digress.

The crash did not lessen the belief of the aforementioned Pattullo that aeroplanes could be of use in detecting the forest fires which devastated British Columbia’s forests decade after decade. Indeed, within days of the crash, the press reported the likelihood that Hoffar Motor Boat was planning to build 2 more flying boats, which would presumably be completed in the spring of 1919. One of those machines could be delivered to the Department of Lands, if required.

Incidentally, Pattullo also thought that aeroplanes, err, seaplanes actually, could be used to fly prospectors into otherwise inaccessible areas of British Columbia. The minister had reached that conclusion as a result of discussions held in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, in August, with various prospectors and / or prospecting firm executives.

Better yet, one of the Hoffar brothers stated that, if orders could be secured, the firm could produce up to 10 aeroplanes a month, aeroplanes which could be used in military flying schools that could be set up in western Canada, presumably in British Columbia.

While the signing of the Armistice, in November 1918, put an end to any British Columbian flying school project, it did not put an end to Pattullo’s forest patrol plans. Indeed, the minister very much wanted to have a flying boat by the start of 1919 forest fire season.

Pattullo’s enthusiasm was soon doused, however, by an analysis conducted by or for the aforementioned Caverhill. Said analysis actually showed that an adequate forest patrol force would require at least 3 flying machines flying twice a day. Operating such a force would cost $ 2.47 to $ 4.94 per square kilometre ($ 6.40 to $ 12.80 per square mile) of land patrolled. By comparison, the average cost incurred at the time by the British Columbian government was 49 cents per square kilometre ($ 1.28 per square mile) of land patrolled. Ow…

As yours truly is wont to do, I will now provide you with information on much all of this would cost using 2023 currency. Operating such a force would cost $ 44.25 or so $ 88.45 or so per square kilometre ($ 114.55 or so to $ 229.10 or so per square mile) of land patrolled. By comparison, the average cost incurred at the time by the British Columbian government was $ 8.85 or so per square kilometre ($ 22.90 or so per square mile) of land patrolled. Ow… Again.

This being said, the project would be feasible…

- if aerial patrols were confined to areas where the fire hazard was extreme,

- if the flying machines were used for aerial survey before and after the forest fire season, and

- if the cost of flying machines fell, as was anticipated / hoped, after the end of the First World War.

Given such information, Pattullo’s deflating enthusiasm was understandable.

The Hoffar H-3 flying boat in one of its elements, Vancouver, British Columbia, 1919. CASM, 5173.

In any event, a small team from Hoffar Motor Boat, a team consisting of the Hoffar brothers themselves perhaps, began to work part time on a 3-seat single engine biplane flying boat in October 1918.

By December at the latest, the brothers might have given a thought to the possibility of using that machine, the Hoffar H-3, for a mail route between Vancouver and Victoria. By January 1919, the possibility of running another mail route, between Vancouver and Nanaimo, British Columbia, was being discussed as well. Both routes were deemed to be feasible, if aeroplanes could be made available. The postmaster of Vancouver, Robert George Macpherson, for example, supported both routes.

This time around, yours truly does know when the designation H-3 made its appearance. Yes, I do. Written (typed?) H3, it was used in the press as early as April 1919.

The Hoffar brothers were not planning to immediately sell their new machine, an improved and slightly larger version of the H-2 worth $ 11 000, which was quite in increase in price. They would use it themselves. Incidentally, that $ 11 000 corresponds to almost $ 180 000 in 2023 currency.

The H-3 might have included ideas that James Blaine “Jim / Jimmie” Hoffar had picked up during his visits of several / many aeroplane manufacturing facilities in the United States. Yours truly wonders if one of those facilities was that of a firm launched in May 1917, Boeing Airplane Company. Yes, that Boeing Airplane, the firm mentioned several / many times in our spectacular blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2021.

The Hoffar brothers test flew the H-3 on 1 May 1919. “Jim / Jimmie” Hoffar was at the controls. He took off and landed, checking all the while how the machine behaved. As the flying boat was about to alight a second time, it hit a log, barely visible in the fading light of day.

The crew of a motor launch which was following the aeroplane picked up the two brothers. The pilot had a slight scalp wound and a seriously sprained leg. His brother was uninjured.

The H-3, on the other hand, was extensively damaged. At one point, only one wing was visible above water. Within a day or two of the crash, the wreckage of the H-3 was towed to shore and moored there. Even so, the two brothers intended to repair their machine and have it ready for flight in late May or early June. That assessment proved mistaken. The H-3 never flew again.

An advertisement of the as yet unincorporated firm United Aircraft of British Columbia Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, singing the praises of the Curtiss JN-4 Canuck it wanted to sell. Anon., “United Aircraft of British Columbia Limited.” Vancouver Daily World, 17 May 1919, 18.

This being said (typed?), the Hoffar brothers did not abandon their aeronautical activities. Nay. Even before the end of May 1919, they were working on the incorporation of a new firm, United Aircraft of British Columbia Limited of Vancouver. You see, the Hoffar brothers had secured the British Columbian sales right for war surplus Canadian-made Curtiss JN-4 Canucks.

A typical example of that 2-seat single engine biplane used to train aviators of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) of the British Army / Royal Air Force (RAF) in Ontario in 1917-18 would cost $ 2 500, a sum which corresponds to approximately $ 40 500 in 2023 currency.

By comparison, a float-equipped Canuck would sell for $ 3 000, a sum which corresponds to more than $ 48 500 in 2023 currency.

Now, I ask you, my reading friend, did any aspect of the preceding paragraph strike you as odd? And yes, that was indeed a trick question. You see, in May 1919, not one float-equipped Canuck would have been seen on our big blue marble. Mind you, not one float-equipped JN-4 Jenny would have been seen either and… Is that a veil of confusion I see over you face, my easily puzzled reading friend?

A brief explanatory digression if I may. Both the Canuck and Jenny were / are derivatives of the Curtiss JN-3, a flying machine developed in 1915 by what was then Curtiss Aeroplane Company, a well-known American firm. Historians and aviation enthusiasts examining photographs of Canucks and Jennies have been pulling their hair out for a century as it could / can be difficult to identify which of the two machines was in front of them. Yours truly does not, however, give in to that exasperation. Nay. No Canuck-ian conniption for me. Nay. My Olympian calm and androgenetic alopecia prevent me from going there and ...

What is wrong with you, my reading friend? The meaning of that terroir / homegrown expression escapes you? Sigh… The quality of education offered in this world has declined significantly since my distant youth. Well, know then that androgenetic alopecia means male pattern baldness. Cur simplici vocabulo uti si tam bene complicatum verbum facit officium? In other words, why use a simple word if a complicated word does its job so well? Is that not the motto of museum curators around the world? (Hello EG, EP, etc.!) Sorry. Back to our story.

To understand how the first float-equipped Canuck made its appearance, you and I will have to travel back in time.

And yes, as you well know, the incredible collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a Canuck.

The American firm at the heart of this aspect of our plot emerged in late November 1918. The main storage facility of United Aircraft Engineering Corporation was located near Leaside, Ontario. The person responsible for that storage facility and the firm’s representative in Canada was Frithiof Gustav “Eric / Fritz” Ericson, the Swedish-born former chief aeronautical engineer of Curtiss Aeroplanes & Motors Limited of Toronto, Ontario, and Canadian Aeroplanes Limited of Toronto.

As the weeks turned into months, and the months into longer periods of time, United Aircraft Engineering sold the multitude of war surplus Canucks it had acquired in January 1919 to a variety of civilian users, both private and commercial, seemingly mainly in the United States.

By the way, Canadian Aeroplanes was a British-controlled firm, controlled via the Imperial Munitions Board, a British body created in November 1915, by the British Ministry of Munitions and Canadian businessmen, to oversee the production of war material in Canada. Created in December 1916, Canadian Aeroplanes was Canada’s first major aeroplane manufacturing firm.

Would I be correct in assuming that you know that Curtiss Aeroplanes & Motors was a subsidiary of Curtiss Aeroplane? Or that it was mentioned in September 2017 and February 2022 issues of our magnificent blog / bulletin / thingee? Or that, again, Canadian Aeroplanes was mentioned several times therein since April 2018? Wunderbar! But I digress.

You will undoubtedly not be surprised to learn that the aforementioned United Aircraft of British Columbia was the property of United Aircraft Engineering and Hoffar Motor Boat.

By mid-May 1919, United Aircraft of British Columbia was preparing to receive 6 Canucks which were to be fitted with the float ensemble developed by the Hoffar brothers. Said ensemble consisted of a large single float under the fuselage and a pair of small stabilising floats near the tips of the lower wings. It was in all likelihood derived from that of the Hoffar H-1, an aeroplane mentioned in the first part of this article.

Mind you, an engineering professor at the University of British Columbia, located in Vancouver, might have helped with the design of the new ensemble.

A second batch of 6 Canucks was scheduled to arrive in the middle of June 1919. Whether or not it arrived as scheduled, if at all, was / is unclear. The same could be said of the 6 aeroplanes scheduled to arrive in September.

In any event, work on the first Canuck floatplane began in early June 1919.

Why was United Aircraft of British Columbia planning to perform the aeronautical surgery which would transform terrestrial aeroplanes into aquatic aeroplanes, you ask, my reading friend? Well, the sad truth was there was still not one real aerodrome in the interior or along the coast of British Columbia where a landplane could operate from. There were, however, a great many lakes and arms / bays / coves / inlets from which a flying boat or floatplane could operate from.

Would you believe that the Hoffar brothers, or one of their representatives, claimed that all 6 float-equipped Canucks had already been ordered by British Columbian aviators? Better yet, they expected to see 50 or so of those machines active in that province during the summer of 1919. That high number might, I repeat might, explain the brothers’ plan to form branches of United Aircraft of British Columbia in Victoria as well as Nelson, British Columbia, and Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

Mind you, the Hoffar brothers were also working on yet another flying boat, an extra strong machine able to alight in bad conditions – and stay afloat. They soon changed their mind, however, and put aside their project in early June 1919.

This being said (typed?), if a high enough prize was offered for the first flight across the Canadian Rockies, that project might have been resurrected. And yes, yours truly realises that a flying boat might not have been an ideal flying machine for crossing an inland mountain chain, but back to our British Columbian Canucks.

The Hoffar brothers’ first customer was an American by the name of Herbert A. “Herb” Munter. He picked up his Canuck, apparently a standard landplane, and promptly flew to Seattle, Washington, where he worked as a barnstorming pilot. A well-known aviator, that gentleman was the former test pilot of the aforementioned Boeing Airplane.

Incidentally, one had to wonder what the management of that firm thought of rumours / news reports according to which United Aircraft of British Columbia might open a branch in its very own backyard, in Seattle.

This being said (typed?), the staff of Hoffar Motor Boat had other fish to fry. It was in fact preparing the first flight of the first Canuck equipped with floats.

It is with a feeling of profound embarrassment that yours truly has to admit that I grossly underestimated the verbosity I expressed in preparing this article. Would you believe that there is enough material left for a 4th part?

I know, I know, but this is where we are.

Ta ta for now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)