Sorry, but no, the Wright brothers did not really invent the airplane: An all too brief overview of the piloted powered heavier than air flying machines fabricated and / or tested before 17 December 1903, part 1

Why such a look of surprise, my easily confused reading friend? You thought that yours truly had forgotten the 120th anniversary of the first controlled and sustained flight of a piloted powered aeroplane, on 17 December 1903, did you not? Yes, you did. Do not deny it. Your ears twitch when you fib.

Actually, if yours truly may be permitted to play devil’s advocate, given the winds which blew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in December 1903, a winged anvil or Steve the kākāpō would have taken to the sky without too much ado. The tricky part was to control one’s trajectory once aloft and… Why the puzzled look, my reading friend? Do you not know Steve the kākāpō? Ahh, such a gaping chasm in your culture cannot remain, err, gaping.

Have a look at the following. I will wait.

Humm, given the amount of snort laughter emanating from your corner of the galaxy, I can only presume that you liked Steve’s down to earth presentation style. Sorry, sorry. (Hello, EP!)

Sadly enough, the kākāpō is a critically endangered species. As yours truly typed this sentence, there were 245 or so kākāpōs living on 4 small islands off the shores of Aotearoa / New Zealand. Yes, 245 or so, not 203.

Now I ask you, what could be more likeable and worthy of survival than a solitary, peaceful, odorous, nocturnal, herbivorous, flightless and curious parrot able to live close to 100 years?

And yes, kākāpōs were doing just fine until Home sapiens set foot on Aotearoa, around 1280-1320 to be more precise. While those people, the Māoris, certainly put a dent in their numbers, both directly and indirectly, British settlers who began to put down roots in the 1810s and 1820s proved far more destructive, both directly and indirectly.

And yes, those pale faced settlers treated the Māoris very poorly, something that will not come as a surprise to the indigenous peoples of every continent on planet Earth, but back to our topic of the day.

To quote the title of today’s pontification, sorry but no, the Wright brothers did really not invent the airplane. The look of puzzlement on your pretty face is giving way to one of outrage, my reading friend? How dare I contest the primacy of the Wright brothers?

Well, for one thing, I am not. Even though the winds which blew at Kitty Hawk were of great help to them in December 1903, the Wright brothers did manage to fly near Dayton, Ohio, during the summer and fall of 1904. By then, mind you, they had begun to use a catapult to facilitate take offs.

And yes, that use of a means to assist their take offs led many individuals in France and Brazil to challenge the Wright brothers’ claim that they had made the first controlled and sustained flight of a piloted powered aeroplane. The many individuals hailing from France gave their allegiance to a French gentleman we will meet before too, too long. The ones hailing from Brazil gave and, in many cases, still give theirs to another gentleman, the Brazilian aeronaut / inventor / sportsman Alberto Santos Dumont.

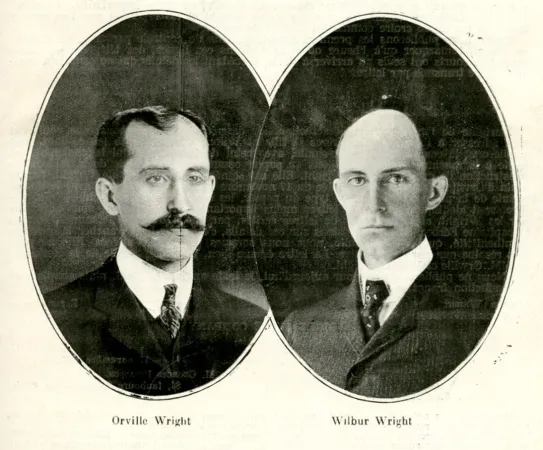

Incidentally, Wilbur and Orville Wright were mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since August 2018. Santos Dumont, on the other hand, was also mentioned many times therein, and this since December 2018, but back to our story.

Yours truly’s contention is that the Wright brothers were the first people on Earth to develop a control system which allowed them to control their flying machines in a three-dimensional space. In other words, they mastered pitch, roll and yaw, and that was how Wilbur Wright managed to remain aloft for an incredible 59 or so seconds on 17 December 1903, covering a distance of 260 or so metres (852 or so feet).

One could argue that the Wright brothers’ familiarity with bicycles, a statically unstable form of transportation, might have resulted in a lightbulb moment of some sort at some point in the late 1890s, but I digress, and…

Do not tell me you did not know that the Wright brothers ran the Wright Cycle Exchange between 1892 and 1895, and Wright Cycle Company, between 1895 and 1909, in Dayton? Sigh… To paraphrase Captain Jean-Luc Picard, a gentleman mentioned in a September 2020, April 2023 and December 2023 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, you should read more history, my reading friend.

Mind you, many individuals seemingly developed, with more or less clarity but before the Wright brothers, 30 or so years before them in two cases, the idea of controlling a flying machines in a three-dimensional space. Individuals like…

- the French engineer / inventor Clément Agnès Ader (1841-1925),

- the English classicist / inventor / amateur scientist Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (1820-94),

- the American engineer / professor Edson Fessenden Gallaudet (1871-1945),

- the French civil engineer Alexandre Goupil (1843-1919),

- the French sea captain / shipowner Jean Marie Le Bris (1817-72), also known as Yann-Vari ar Brizh,

- the (German?) American businessman / industrialist / inventor Johann Ferdinand Hugo Mattullath (1840-1902),

- the American engineer / inventor / glider pilot / professor John Joseph Montgomery (1858-1911),

- the French engineer / professor Louis Pierre Marie Mouillard (1834-97), and

- the French engineer / inventor Charles Alphonse Pénaud (1850-80).

This being said (typed?), the numerous individuals who fabricated and / or tested piloted powered heavier than air flying machines before the Wright brothers seemingly did not realise the importance of such a control system

You may be pleased, or not, to hear (read?) that Ader was mentioned in a September 2022 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and…

Yes, yes, my sceptical reading friend, yes, numerous individuals fabricated and / or tested piloted powered heavier than air flying machines before the Wright brothers. You do not believe me, now do you? O ye, of little faith.

Well, fasten your seatbelt, kitten, and enjoy this ride down the yellow brick road of memory lane.

3, 2, 1, go!

Jean-Marie Félix Rivallon du Temple de la Croix, circa 1870-71. Bibliothèque nationale de France, P082165.

The steam-powered aeroplane of Jean Marie Félix Rivallon du Temple de la Croix. J. Lecornu. La Navigation aérienne : Histoire documentaire et anecdotique. (Paris: Librairie Vuibert, 1913), 125.

If one is to believe the doxa, in other words popular opinion, Commander Jean Marie Félix Rivallon du Temple de la Croix (1823-90) was still an officer in the French Marine impériale when he and a small team began, in 1869-70, in Cherbourg, France, the construction of a monoplane flying machine patented in May 1857, a flying machine powered by a steam engine designed by du Temple de la Croix and his older brother, who was also an officer in the Marine impériale, Commander Jean Louis Antoine Rivallon du Temple de la Croix.

Completed in 1874, that aeroplane was tested several times from the top of an inclined plane. On one occasion, the young sailor who was at the controls allegedly found himself aloft for a few seconds. The French aeroplane could therefore be described as the first piloted powered heavier than air flying machine to achieve flight, albeit a brief and uncontrolled one.

The catch with those assertions was / is that a seemingly well documented article in the 21 December 1885 issue of the French weekly science popularisation magazine Cosmos asserted that the aeroplane of du Temple de la Croix had yet to be tested. Fearing failure and ridicule, the latter had decided not to tempt fate.

Indeed, yours truly has been unable to locate a single mention of the aforementioned hop in the French press of the 1870s and 1880s. The French American civil engineer / aviation pioneer Octave Chanute had been equally unable to find a single mention during research undertaken in the early 1890s. Books or magazines published before 1914 mentioned tests carried out with at least one scale model, but nothing more. Could the doxa be wrong? Might the hop of the aeroplane of du Temple de la Croix be pure invention? Yours truly must admit to being increasingly skeptical. You be the judge.

A 1963 Soviet stamp adorned with a portrait of Captain First Rank Aleksándr Fodorovich Mozháyskiy and an artist’s impression of his steam-powered aeroplane. Wikipedia.

A 1974 Soviet stamp adorned with an artist’s impression of the steam-powered aeroplane designed by Captain First Rank Aleksándr Fodorovich Mozháyskiy. Wikipedia.

Captain First Rank Aleksándr Fodorovich Mozháyskiy (1825-90) was an officer, possibly of Ukrainian origin, in the Rossiyskiy imperatorskiy flot, in other words the imperial Russian navy, living in Sankt-Peterburg / Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, when he set out to build a steam powered aeroplane, in 1882, in the nearby village of Krásnoe Seló, Russian Empire. At some point between 1882 and 1885, an unidentified pilot tried to take off from an inclined plane. The underpowered monoplane proved unable to lift off, possibly tilted to one side and crashed, possibly injuring its pilot.

A brief digression if I may. From March or April 1948 onward, several Soviet military and civilian publications began to put forward the idea that Mozháyskiy had invented the first aeroplane, and this more than 20 years before the Wright brothers.

In January 1949, for example, the Soviet daily newspaper Komsomol’skaya Pravda stated that Mozháyskiy’s aeroplane, an amphibian piloted by a certain Golubev, had successfully flown in July 1882. And yes, Mozháyskiy’s aeroplane was more advanced than that of the Wright brothers.

Neener, neener, or so seemed to claim the official organ of the central committee of the Vsesoyuznyy Leninskiy Kommunisticheskiy Soyuz Molodozhi of the Kommunisticheskaya Partiya Sovetskogo Soyuza, in other words the all-union Leninist communist youth league of the communist party of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Incidentally, the Golubev in question was apparently a young self-taught mechanic by the name of Ivan Nikiforovich Golubev.

According to an article published in a December 1949 issue of the Soviet illustrated weekly magazine Ogoniok, Golubev, the first aeroplane pilot in history, was born near Kaluga, Russian Empire, a city which happened to be the place near which the Russian / Soviet pioneer of cosmonautics Konstantín Eduárdovich Tsiolkóvskiy, a person mentioned in a February 2019 issue of our all-encompassing blog / bulletin / thingee, spent most of his life. A pure coincidence of course.

Would you believe that the aeroplane was but one of a series of scientific and technological firsts claimed by the USSR in the late 1940s and the early to mid 1950s, from insulin, penicillin, steam engine, radio communication and incandescent lightbulb to the existence of the atomic nucleus and the discovery of the electrical nature of lightning?

As one might expect, given the Cold War the world was suffering from at the time, American and pro-American sources tended to dismiss such claims as more or less preposterous propaganda exercises.

A rather scathing cartoon which expressed the opinion of many Americans, and Canadians, regarding the Soviet claims concerning Captain First Rank Aleksándr Fodorovich Mozháyskiy’s flight of 1882. Anon., “Ivan the Terrible Fibber.” Sunday World Herald, 2 January 1949, 2-E.

This being said (typed?), the truth was…

- that the famous Russian polymath Mikhail Vasil’yevich Lomonosov was one of the individuals who had conducted experiments on atmospheric electricity in the early 1750s;

- that the Russian inventor Ivan Ivanovich Polzunov oversaw the construction of the first two-cylinder steam engine, in the mid-1760s, an engine which could be used away from large sources of water, another world first;

- that the Russian doctor Vyachesláv Avksént’yevich Manasséin had discovered the antibiotic properties of certain molds in the early 1870s, and suggested their use for the treatment of wounds;

- that the Russian electrical engineer / inventor Aleksandr Nikolayevich Lodygin was one of the individuals who had developed incandescent lightbulbs in the 1870s;

- that the Russian historian / lawyer / philosopher / publicist / teacher Borís Nikoláevich Chichérin was one of people who had taken for granted the existence of the atomic nucleus in the late 1880s;

- that the Russian inventor / physicist / science populariser / teacher Aleksándr Stepánovich Popóv was one of the individuals who had developed a radio wave detecting device in the mid 1890s but was not the first to transmit radio messages; and

- that the Russian pathologist / physiologist Leonid Vasil’yevich Sobolev thought in the early 1900s that problems with certain parts of the pancreas might be the cause of diabetes.

Dare one suggest that, in the late 1940s and the early, mid and late 1950s, the governments of the United States and its allies tended to look down on the USSR? It was, many claimed, a militarily mighty if technologically backward country. Such assumptions proved to be mistaken. One only needed to consider the shock caused by the appearance of Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 jet fighters in the skies of the Korean peninsula in late 1950 or the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, in October 1957, but I digress.

And yes, you are quite correct, my reading friend, the astounding collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a MiG-15. Well, the aircraft in question is actually a WSK Lim-2, in other words a MiG-15 made in Poland, but I will give you a gold star anyway.

A 1938 French stamp adorned with a portrait of Clément Agnès Ader and a drawing of his Avion III. Wikipedia.

A slightly outlandish artist’s impression of Clément Agnès Ader’s Éole steam-powered aeroplane in flight. Anon., “Les nouveaux aérostats [sic] – L’oiseau de M. Ader.” La Science française, 12 September 1891, 17.

Clément Agnès Ader (1841-1925) was a French engineer / inventor who, in 1890, supervised the construction of an aeroplane of his own design, a flying machine whose folding wings were inspired by those of an otherwise unidentified species of flying fox / fruit bat. The Éole was fitted with an alcohol-fired steam engine Ader had designed himself, an engine far superior in power and power to weight ratio to the one used a decade later by the Wright brothers.

Ader lifted off the ground on 9 October 1890, at Gretz-Armainvilliers, France, near Paris. His 50 or so metre (165 or so feet) uncontrolled hop was witnessed only by a few people who worked for him. Ader had accomplished the unassisted first take off of a piloted powered aeroplane from a flat surface.

Confirmation of that contested hop came in 1937 when a crucial discovery was made. Someone found the small pieces of coal that Ader’s assistants had put in the ground to indicate where the Éole had taken off.

Intrigued by the potential of Ader’s flying machine, the Armée de Terre allowed the inventor to test it on one of its bases, near Satory, France, in September 1891. It was and still is unclear whether or not the Éole managed to make another uncontrolled hop at that time. Even so, the Ministère de la Guerre was sufficiently intrigued to finance the construction of an improved aeroplane.

Soon after that decision, in 1892 perhaps, Ader began to supervise the construction of a second aeroplane, the Zéphyr. For some reason or other, that machine was never completed.

The Avion III steam powered aeroplane of Clément Agnès Ader at the first Exposition internationale de locomotion aérienne, Paris, France, September or October 1909. Max de Nansouty. Aérostation – Aviation. (Les Merveilles de la Science, no. 4) (Paris: Boivin & Compagnie, 1911), 524.

Ader completed another bat-like steam-powered aeroplane, also financed by the Ministère de la Guerre, in 1897. He was at the controls of that twin-engine Avion III during trials held near Satory in October. On 14 October, having underestimated the slope of the land on which the circular track he was planning to follow had been built, Ader almost immediately found himself aloft. As he attempted a turn, a gust of wing hit the Avion III, pushing it off the track. Ader’s creation crashed. Ader himself was uninjured.

Even though his aeroplane managed to make several hops over a distance of 300 or so metres (985 or so feet), the members of the military commission present on the scene were not exactly impressed. Ader’s funding was cut, which brought to an end his plans to build the gasoline-powered Avion IV.

Exhibited at the site of the Exposition universelle de 1900, held in Paris between April and November, the Avion III was among the aeroplanes exhibited at the first Exposition internationale de locomotion aérienne, held in Paris in September and October 1909.

In 1902, Ader donated the Avion III to the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers, a renowned French higher learning institution specialising in science and technology education and in the dissemination of such knowledge.

The Musée des arts et métiers, the oldest science and technology museum on planet Earth and a component of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers, is well worth the visit, trust me. After all, you will see many wonderful things, including, yes, including the Avion III, the oldest piloted powered heavier than air flying machine on planet Earth.

The hybrid flying machine designed and built by Edward Purkis Frost, West Wratting, England, circa 1892. Octave Chanute. Progress in Flying Machines. (New York: The American Engineer and Railroad Journal, 1894), 34.

Edward Purkis Frost (1842-1922) was a well off and well connected English justice of the peace / livestock breeder who, at some point in the mid 1860s or early 1870s, began to work on a flying machine, at West Wratting, near Cambridge, England. He completed a hybrid flying machine, half ornithopter, half aeroplane, with 8 wings covered with artificial feathers or silk in late 1891 but found himself unable to locate a sufficiently light and powerful (gasoline?) engine, and…

I know, I know, the aforementioned doxa is of the opinion that Frost completed that flying machine in 1877. The problem with that assertion is that the only articles on that aeroplane that yours truly could find dated from 1891-92. Could the doxa be wrong? You be the judge.

And yes, Frost was mentioned in an August 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Major Ross Franklin Moore (1847-1923) was a British Army officer who served in the British Raj, today’s Pakistan, Myanmar, India and Bangladesh, with the Corps of Royal Engineers. While stationed in Rangoon, British Raj, today’s Yangon, Myanmar, in 1890, he contacted a small engineering firm, Messrs. J. Shaw & Sons of Coventry, England, and asked that it build an ornithopter whose design was based on that of an as yet unidentified species of bat.

Realising a few months or so into the project that the chiropteran he had chosen would not do, seemingly as a result of experiments conducted in or near Rangoon, Moore chose another bat species, a flying fox species to be more precise, that yours truly has yet to identify. Small world is it not?

In any event, work on the new design began in Coventry in early 1891. Completed in early 1892, not too long before Moore’s retirement, in July, and, presumably, before his return to England, that tethered ornithopter was fitted with an electric motor linked by cables to one or two high voltage power lines. It was to be used as an aerial (civilian?) survey or (military?) observation platform. Seemingly tested near Coventry, that utterly unique flying machine proved unable to fly.

Interestingly, Moore immigrated to Canada around 1910. He died in Victoria, British Columbia, in June 1923, at the age of 76.

And that is it for today, my reading friend. Do not forget to come back soon…

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)