“Reds Carry Cold War to North Americans:” A brief roadmap of the circumstances surrounding the importation of Czechoslovakian automobiles into Canada at the height of the Cold War, part 2

Dobrý den, můj čtenářský přítel, a vítám vás u této druhé části našeho článku.

Um, hello, my reading friend, and welcome to this second part of our article. You will of course remember that said second part will complete our examination of the reaction of various stakeholders to the importation into Canada of automobiles produced in Czechoslovakia by the state firm Automobilové Závody Národni Podnik (AZNP), during the 1950s.

An interesting aspect of that story was / is that, in the spring of 1950, Canadian automobile distributors / dealers and Canadian and British automobile manufacturers petitioned the federal government to block the importation into Canada of automobiles produced in Czechoslovakia, a communist country. Those low-cost automobiles competed with vehicles produced by Canadian workers.

This being said (typed?), Canadian automobile distributors / dealers and Canadian automobile manufacturers also complained about competition from automobiles manufactured in the United Kingdom or elsewhere in Europe.

How could European automobile manufacturers dare to sell Canadian consumers vehicles which were more economical in all aspects than the 4-wheeled mastodons produced in North America in 1950? Sorry, sorry.

Yes, yes, automobiles manufactured in the United Kingdom or elsewhere in Europe. Indeed, with all due respect to Brexiteers, those British citizens, a majority of them disoriented / frightened / uncertain Englishmen and Englishwomen, the United Kingdom was, is and always will be a European country, but I digress.

Contacted by the Canadian Press in the hours following the moment when the dark affair of sabotage mentioned in the first part of this article broke out, a spokesperson for an unidentified ministry of the federal government declared that the latter would not impose an embargo on imports to Canada of Czechoslovakian automobiles. Since Czechoslovakia had signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, in 1948 I think, an agreement also binding on Canada, the federal government had to consider it to be one of the most favoured nations favoured by said agreement.

The only potential obstacle to the importation of Czechoslovakian automobiles into Canada would have been the Emergency Exchange Conservation Act which had come into force in July 1948. Czechoslovakia being one of the many countries whose currency, the Czechoslovakian crown, then had a fixed exchange rate with the British pound sterling, however, the law in question was not an obstacle either.

Even recourse to Canada’s antidumping regulations, for all intents and purposes abandoned during the Second World War, was not an option. In any case, no one really knew how to determine the fair market value of an automobile produced behind the Iron Curtain. Worse still, the application of said antidumping regulation was likely to clobber one, if not two British automobile manufacturers of secondary importance who were selling vehicles in Canada.

In any event, AZNP and the Czechoslovakian state firm Tatra Národní Podnik had permits allowing them to import up to 1 600 vehicles into Canada in 1950, a total which could well be increased before the end of the year.

A somewhat impertinent comment if I may. Considering the fact that Canadian firms manufactured approximately 284 075 automobiles in 1950 and that the total number of vehicles imported by firms from the rest of the world came to approximately 6 775, one was entitled to wonder why spokespersons for the Canadian automobile industry were climbing the curtains at the announcement that Établissements Cotton Incorporée of Québec, Québec, one of the firms at the heart of our article, wanted to import several hundred Czechoslovakian automobiles, but I digress.

And yes, those spokespersons for the Canadian automobile industry initially seemed to have thought that the anti-communism of Canadians would have been more than enough to stem the flow of communist automobiles.

And the fact was that this argument worked in more than one case. According to an unidentified Toronto, Ontario, automobile dealer, yes, yes, the same one mentioned in the first part of this article,

They come in, look the car over. They say they like it but not where it comes from. They don’t like the idea of buying something made in a country under Soviet domination.

I try to reason with them. We’ve got to try and get along with the Russians. That goes for politics as well as trade. I pay for these cars in Canadian dollars through a Montreal bank. The Czechs draw on it to buy Canadian goods they want.

This being said (typed?), the fact was that a number of people were considering the possibility of acquiring a more economical automobile than the typical North American mastodon regardless of its provenance, provided of course that it was reliable and durable, but back to the dark story mentioned in the first part of this article.

However plausible might have been the suggestion that the damage to the Czechoslovakian automobiles imported by Établissements Cotton was due to bad weather in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean or, perhaps, negligent handling at the port of Saint John, New Brunswick, the fact was that, at almost the same time, in Vancouver, British Columbia, the general manager of Campbell Motors Limited, a major automobile seller, made an interesting statement to say the least.

William M. “Billie” Campbell claimed that pilferers had removed 15 or so clocks and several tool kits from a lot of Škoda 1101 / 1102s and Tatra 600s located on a quay in the port of Vancouver.

And yes, the automobiles in question had arrived in British Columbia by ship. Yours truly assumes that the cargo ship in question had crossed the Atlantic Ocean before passing through the Panama Canal, then sailed north into the Pacific Ocean.

Did that theft of clocks and tool kits confirm the assertion of Randall Cotton, the founding president of Établissements Cotton and Cotton Motor Sales Company Limited of Québec, according to which dark forces in Canada were trying to harm the import of Czechoslovakian automobiles? Not necessarily. You see, British Columbian firms which imported British automobiles reported that the pilfering of clocks, fog lights, mirrors and tool kits was quite frequent.

This being said (typed?), no one seemed to know if those misdeeds were committed in Europe, during the crossing or at the port of Vancouver – or in more than one place.

A brief digression if I may. According to an importer of British automobiles from the Vancouver area, I presume, a batch of vehicles had suffered more or less serious damage during the second half of the 1940s. You see, a shipment of alcohol was on board the same cargo ship, in a hold next to the one where the vehicles were located.

And yes, my reading friend with a lot of life experience, you guessed right. Several / many sailors had cut the wall of said hold in order to access the hooch. Around 200 (!?) cases of alcohol disappeared during the crossing. The transfer of that loot took place across the hoods and / or roofs of the automobiles, all of which had suffered damage. History did / does not say whether the culprits were identified.

Incidentally, 6 Škoda 1101 / 1102s belonging to Cotton Motor Sales and 50 British automobiles belonging to an automobile dealer, McGrail Motors Limited of Montréal, Standard / Triumph Mayflowers if you want to know, were damaged in early July 1952 at the latest while they were located on a storage site in Montréal. Many windows were smashed and many accessories, from ashtrays to door handles to tires, went missing, and...

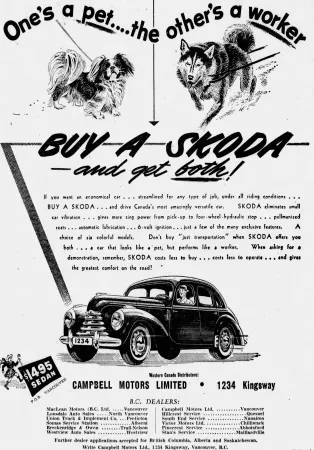

What is Campbell Motors doing in our history, you ask, my reading friend? A good question. It turned out that this firm was the distributor of the Czechoslovakian automobiles for Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan). Better yet, by May 1950 at the latest, Campbell Motors could count on 8 dealerships in British Columbia. It had 12 in June at the latest. The following illustration might prove interesting in that regard.

An advertisement of Campbell Motors Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, extolling the virtues of the AZNP Škoda 1101 or 1102 automobile. Anon., “Campbell Motors Limited.” The Vancouver Daily Province, 9 May 1950, 5.

And yes, you read correctly, my reading friend: “Absolutely free a two week holiday in California every year… with the new SKODA… Believe it or not!” According to Campbell Motors, there was a difference of about $400, or about $5 100 in 2023 currency, between the annual operating costs of a Škoda 1101 / 1102 and those of a large North American automobile, enough to pay for said holiday in California.

The expression “Believe it or not!” was / is obviously inspired by the famous eponymous franchise created in December 1918, initially under the name “Champs and Chumps,” by the American amateur anthropologist / adventurer / designer / entrepreneur / explorer / journalist LeRoy Robert Ripley.

The following ad might intrigue / amuse you a little…

An advertisement of Campbell Motors Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, extolling the virtues of the AZNP Škoda 1101 or 1102 automobile. Anon., “Campbell Motors Limited.” The Vancouver Sun, 12 May 1950, 4.

It went without saying that Campbell Motors wanted to expand its dealer network in Alberta and Saskatchewan. It seemed to get pretty good results.

By the way, the Škoda 1101 / 1102 sold for between $1 495 and $1 745 in British Columbia in 1950, a sum which corresponds to between approximately $19 050 and $22 250 in 2023 currency. The least expensive American automobile apparently cost between $500 and $700 more, which translated to between about $6 375 and $8 925 in 2023 currency, or between 35 and 40% more, which was no small thing you will admit.

The first six Škoda 1101 / 1102s arrived in British Columbia in January 1950. And here is proof…

A posed photograph showing two employees of Campbell Motors Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, in the company of an AZNP Škoda 1101 or 1102 convertible. Anon. “Picture Parade.” The Vancouver Daily Province, 14 January 1950, 32.

Another posed photograph showing the same two employees of Campbell Motors Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, in the company of an AZNP Škoda 1101 or 1102 convertible. The firm’s manager, William M. Campbell, was in the back seat of the vehicle. Anon., “Toe does the work – Grease Job Thing of Past With Midget Czech Auto. » The Vancouver Sun, 16 January 1950, 13.

Campbell Motors had apparently ordered no less than 450 Czechoslovakian automobiles.

The reception given to the Škoda 1101 / 1102 by The Vancouver Sun of… Vancouver could not have been more positive. Let us cite for example the author of the column “Sincerely yours by Ann Drummond” who had this to say in February 1950.

The SKODA is any woman’s idea of what a small car should look like. A demonstration in this streamlined Czechoslovakian auto was thrilling. The SKODA has a remarkably rich appearance. Every minute detail has been attended to and the finished product is so outstanding you’ll want one on sight.

The Cold War? Never heard of it.

Before I forget, the first batch of 6 Tatra 600s arrived at the port of Vancouver from Antwerpen, Belgium, in March 1950 aboard the cargo ship MS Uruguay of the Johnson Line of the Swedish shipping company Aktiebolaget Nordstjernan. Other cargo ships were due to leave shortly the ports of Antwerpen, Hamburg and Trieste in Belgium, West Germany and the Free Territory of Trieste.

Would you believe that the founding president of Campbell Motors, Malcolm D. “Jock” Campbell, then retired, had gone to Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1949 or 1950, to negotiate the purchase of Tatra 600s and, in all likelihood, that of the Škoda 1101 / 1102s?

And yes, yours truly has noticed, just like you, my reading friend, that the media coverage of the British Columbian press concerning Czechoslovakian automobiles far exceeded that of the Québec press.

This being said (typed?), a daily newspaper of secondary importance in Québec, the city, L’Événement-Journal, published a quasi-editorial on that question, whose following quotes are translated here, in April 1950, the very day of the publication of the first articles on the possible sabotage of some of those vehicles.

“Whatever the motive for sabotaging a shipment in transit, that crime will embarrass federal authorities and undermine the success of Canada’s trade relations.”

If greater freedom of trade was to the advantage of the workers who manufactured the exported items and of the consumers who bought them,

it sometimes happens that change temporarily disconcerts the habits of a country. One cannot expect a domestic industry to look favorably on declining sales or consumers to understand that exporting farm products increases the cost of food for her or him.

L’Événement-Journal went on to conclude that “criticism has its reason for being, but not sabotage.”

A rather interesting article also appeared in a September 1950 issue of the weekly newspaper / magazine of the Ligue ouvrière catholique, a movement subject to the roman catholic church of Québec. The unidentified author of the text published in Le Front Ouvrier denounced Cotton’s “merchant’s reasoning,” a title translated from the original “Le raisonnement de commerçant.”

The businessman had indeed made the following comment in August 1949, in a translation of a contemporary translation:

Czechoslovakia being behind the Iron Curtain, many customers may be opposed to the purchase of Skoda cars. But with the trade deal between this country and ours being in the ratio of three to one, interest trumps politics. For every Canadian dollar we spend in Czechoslovakia, they buy three dollars worth from Canada. If all countries in the world observed a similar balance, Canada would be the most prosperous country in the world.

Cotton had no objection to trading with communists if there was money to be made. Indeed, according to the weekly, he seemed to all intents and purposes to take the Czechoslovakians for suckers.

The unidentified author of the text published in Le Front Ouvrier did not, however, limit himself to a simple denunciation of Cotton’s candid admission. Nay. International trade was at an impasse according to many, he pointed out, because dollar zone countries, Canada for example, insisted on selling more products abroad than they bought.

Perhaps worse still, in translation,

neither gold nor silver is wealth. These are just signs that represent wealth. What is the use of having many signs if the true riches are beyond our reach, shipped to foreign countries?

Since when is the reflection, the image, preferable to the thing?

Let us mention in passing that Établissements Cotton was very sensitive to the power of the image. In November 1950, for example, that firm presented a magnificent Škoda 1101 or 1102 convertible to a young secretary, Jacqueline Gilbert, the winner of the Miss Cinéma 1950 competition organised by a popular Montréal weekly, Le Petit Journal, a short-lived Montréal film production company, Quebec Productions Corporation, and a popular Montréal radio station, CKVL.

Indeed, people associated with the competition traveled for a few months, from spring to autumn 1950, aboard a similar but slightly less luxurious vehicle, decorated with mentions of the Miss Cinéma 1950 competition.

People who saw that vehicle passing by were asked to send a note including their name and address as well as the location and date of their sighting. One of those notes was chosen at random in November 1950. The person who had sent it then won a magnificent motorcycle manufactured by the Czechoslovakian state firm Moto Jawa Národni Podnik, a firm represented by… Cotton in eastern Canada, through Établissements Cotton Cycles (Incorporée?) of Québec.

Would you believe that it then cost 3 cents to post in Montréal a letter intended for Montréal, and 4 cents to post elsewhere in Québec a letter intended for Montréal? Those amounts correspond respectively to 38 and 51 cents in 2023 currency, amounts much lower than the cost of a stamp in this year of woe 2023.

Before I forget, let me mention that Gilbert’s film career unfortunately did not take off. This being said (typed?), she became a well-known model on the Canadian fashion scene of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

In May 1951, Établissements Cotton presented another magnificent Škoda 1101 or 1102 convertible to one of the most popular artists in the Québec region. The Franco-American Christo Christy, born Émilien Conrad Ouellette, had indeed won the RadioMonde plaque awarded, I think, to the most popular radio announcer in said region.

Before I forget, launched in January 1939, the Montréal weekly RadioMonde was the first francophone Québec / Canadian magazine devoted to radio artists, but back to our story.

While it was true that Czechoslovakian automobiles were available in Canada around 1949-51 and around 1958, yours truly was unable to confirm whether their importation continued uninterrupted throughout the 1950s. The same went for the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

The presence of several AZNP Škoda 1200 automobiles on the site of the 1954 edition of the Canadian International Trade Fair, held between 31 May and 11 June on the site of the Canadian National Exhibition, in Toronto, seemingly did not generate much interest among Canadian dealers.

And no, Czechoslovakia did not participate in the 1951, 1952 and 1953 editions of that international fair. Yours truly wonders if the Korean War had anything to do with that. Just sayin’.

As far as yours truly can figure out, Czechoslovakian automobiles might not have returned to Canada until the fall of 1957 when the Czechoslovakian foreign trade company Omnitrade Limited could count on a network of dealers located in Ontario, Québec and Atlantic Canada.

The automobiles in question, by the way, were AZNP Škoda 440s, the automobile with which we began the first part of this article of our utterly unbelievable blog / bulletin / thingee.

Your increasingly agitated air indicating to me how much you wish to be somewhere else, my reading friend, I will put an end to this peroration without further delay.

Speaking (typing?) of being somewhere else, yours truly would be remiss if I did not bring to your attention the best line of the very impressive American space opera type television series Babylon 5, broadcasted between January 1994 and November 1998. To quote Delenn, the Minbari ambassadress on the Babylon 5 space station: “Only one human captain has ever survived battle with a Minbari fleet. He is behind me. You are in front of me. If you value your lives, be somewhere else!”

And yes, Babylon 5 is one television series I would not mind seeing again rather than having to endure constant and incessant repeats of the innumerable series of the Star Trek franchise. (Sorry, EG.)

Na shledanou a měj se krásně.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)