I have been asked a few times what my favourite airplane was. Well, here is one of my all-time favourites: Sweden’s FFVS J 22 fighter plane, part 1

Greetings, my reading friend. Yours truly hopes that you will forgive this decision on my part to offer myself a tiny gift on this April Fool’s Day. While I cannot explain why this is so, I must admit that Sweden’s FFVS J 22 fighter plane is indeed one of my all-time favourite airplanes.

And yes, you are quite correct, my all-seeing and all-knowing reading friend, Looping was the monthly magazine of the Kungliga Svenska Aeroklubben. And you are the one who is digressing. As usual. So back to our story.

One could argue that the story of the J 22 began in the spring of 1940, when the “phony” stage of the Second World War ended with a bang, namely the invasion / occupation of Belgium, Denmark, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, Norway and the northern half of France by National Socialist Germany.

Sweden’s access to the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean was now subject to every whim of its supremely evil neighbour, whose Kriegsmarine patrolled the waters between Norway and Denmark, and to every whim of the far the more powerful and utterly non evil navy of the United Kingdom, the Royal Navy, which patrolled the waters of the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

As this was taking place, one of the Baltic Sea neighbours of Sweden, Finland, was picking itself up after a savage 105 or so day war (November 1939-March 1940) with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). In June 1940, that evil empire sent ultimatums to the governments of three tiny Baltic Sea neighbours of Sweden, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania: accept incorporation within the paradise of the proletariat or be forced into it. Soviet troops arrived within days. Sweden now found itself pretty well surrounded.

At the time, Sweden had been a neutral country for more than 125 years. Its armed forces were no match for those of National Socialist Germany or the USSR. While it was true that the Swedish arms industry had supplied and could, to a large extent, continue to supply the Armén and Marinen, the situation was not quite as rosy in the case of the Swedish air force, or Flygvapnet.

You see, the Swedish aircraft industry was quite small and unable to quickly produce the high-performance aircraft needed to defend Sweden’s neutrality. Even before the invasions of 1940, the government knew that British or French aircraft manufacturers could offer no assistance. Indeed, the aircraft industries of the United Kingdom and, even more so, France were unable to produce all the aircraft that the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Armée de l’Air wanted to operate. The acquisition of German aircraft was also considered but the government of that other evil empire was not willing to help.

Back in 1936, when the Flygvapnet and the Swedish department of defence, the Försvarsdepartementet, launched a modest rearmament plan, the main effort (4 of the 5 new non-naval combat aircraft) was put on the acquisition and / or production, on Swedish soil, of aircraft used for bombing (light / attack and medium) and reconnaissance. These aircraft were to protect the country against a seaborne invasion and an associated aerial onslaught. The main goal of the medium bombers, for example, was seemingly to attack the bases from which enemy bombers would take off to attack Swedish cities, terrorise the population and force the Swedish government to surrender. The latter approach was to some extent based on the writings of a renowned Italian air power theorist, major general Giulio Douhet, the best known of which being Il dominio dell’aria, in English The Command of the Air, initially published in 1921.

A catch, if not the catch, with the Flygvapnet’s plan was that the 55 or so German- and Swedish-made Junkers B 3 twin-engine medium bombers delivered between 1936 and 1941 were all but obsolete by the time the Second World War began. In any event, there was no way on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth that these machines could have deterred the 1 200 or so twin-engine medium bombers that the Luftwaffe, the air force of National Socialist Germany, operated as early as September 1939. Worse still, even if the B 3s had managed through some miracle to reach one or more targets in Germany without being detected, the 1 200 or so single- and twin-engine fighters the Luftwaffe had as early as September 1939 would have all but obliterated that force before it could return to Sweden, but back to our rearmament story.

In 1936-37, the big wigs of the Flygvapnet and Försvarsdepartementet seemingly did not realise the level of destruction that a sizeable force of modern bombers was capable of. Indeed, no one realised the level of destruction that a sizeable force of modern bombers was capable of.

What happened in Gernika in April 1937, in other words the bombing of that Basque / Spanish town during the Spanish Civil War by German aerial thugs, came as a shock. The bombing of the capital city of Poland, Warszawa / Warsaw, in September 1939, by a far greater number of German aerial thugs, fully opened the eyes of the big wigs of the Flygvapnet and Försvarsdepartementet to what would happen to Swedish cities if the country was attacked. The fighter units of the Flygvapnet were too few in number and their aircraft were obsolete – and quite possibly slower than the bombers they could be asked to attack.

To the shock of the onset of the Second World War, in September 1939, should be added the aforementioned unprovoked war unleashed by the evil Muscovite empire, in other words the USSR, against Finland in November 1939.

This being said (typed?), an effort had been launched in April 1939 to design a fighter plane in Sweden. When informed of this, one of the country’s few aircraft manufacturing firm, a shipbuilder involved in aviation in fact, Aktiebolaget Götaverken, indicated to the Swedish authorities that it was withdrawing from aircraft manufacturing. This being said (typed?), again, it pointed out that a small firm formed as result of that decision, Aktiebolaget Flygplanverken, would be interested in submitting a bid. Götaverken’s ex-chief aeronautical engineer and founder of Flygplanverken, Bo Klas Oskar Lundberg, was very interested indeed. He submitted a proposal for an aircraft known as the GP 9, no later than September 1939.

The other team involved in the fighter plane plan worked for Aktiebolaget Svenska Järnvägsverkstädernas Aeroplanavdelning (ASJA). Its design was known as the L 12. Mind you, American engineers present in Sweden between 1938 and 1940 to help ASJA produce under licence a pair of American machines, an advanced training aircraft and an attack / dive bombing aircraft, may well have lent a hand to that project.

In any event, it so happened that, in 1939, ASJA was in the process of being absorbed by a recently created (1937) aircraft manufacturing firm, Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget (SAAB). Yes, that SAAB, the automobile manufacturer. And this explained why the second of two fighter plane proposals submitted, again no later than September 1939, bore the designation SAAB 19.

And yes, my inquisitive reading friend, Lundberg had indeed worked for ASJA before joining Götaverken’s staff.

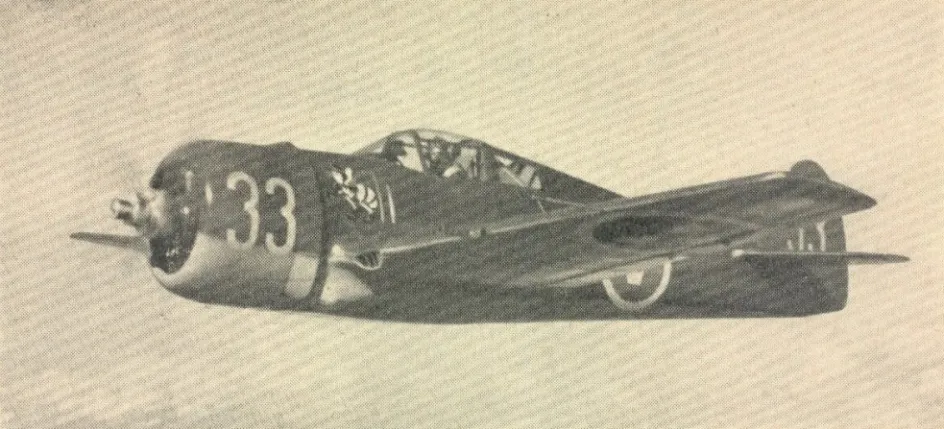

Oddly enough, the SAAB 19 bore more than a passing resemblance to one of the most iconic fighter planes of the 20th century, the standard aircraft carrier-based fighter plane of the imperial Japanese navy, or Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun, the Mitsubishi A6M. And yes, that resemblance was a coincidence, and… Do not even think of going paranoid on me, my reading friend, there are enough wackadoodles, anti-vaxxers, conspiracy theorists, b*llsh*t peddlers and plain nutters around as it is!

Unfortunately, fortunately actually given Sweden’s situation, SAAB also had another pair of projects on its plate: the SAAB 17 single engine bomber and the SAAB 18 twin engine medium bomber, respectively flight tested in May 1940 and June 1942.

While interested in the GP 9 and SAAB 19, all the parties involved knew only too well a prototype of the machine chosen by the Flygvapnet would not fly before 1941. Worse still, it would probably not enter service before 1943. In any event, the British government showed no interest in selling the engines that the chosen aircraft would need. And so it was that the GP 9 and SAAB 19 went bye bye in December 1939, but back to our story.

The Swedish government thus found itself trying to obtain fighter planes as quickly as humanly possible from the country where its British and French counterparts, not to mention its Belgian, Dutch, Norwegian, etc. counterparts, had been conducting business since 1938. That country was the United States.

Between May 1939 and January 1940, for example, the aviation administration / air board, or Flygförvaltningen, signed a trio of contracts with Seversky Aircraft Corporation, a troubled firm which became Republic Aviation Corporation in September 1939, some months after its founder, the flamboyant Russian-American pilot and businessman Alexander Prokofiev “Sasha” de Seversky, born Alexandr Nikolaevich Prokofev-Severskii, was removed from the presidency. Said contracts were for the Seversky EP-1, an export version of the Seversky P-35 fighter plane, a type flown by the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) which was no great shakes, and…

You have a question, my reading friend? Shoot. Why did the Flygförvaltningen and Flygvapnet choose the EP-1 if it was no great shakes? Well, the sad truth was that American firms which produced somewhat better machines, the export version of the Curtiss P-36 fighter plane for example, already had full order books. This being said (typed?), I am puzzled by the fact that the single-seat aircraft sold to Sweden were significantly slower than the Seversky 2PA two-seat long range escort fighter / fighter bomber tested in England by the RAF in 1939.

How troubled was Seversky Aircraft, you ask, my concerned reading friend? Well, let me tell you. In the late summer of 1938, that firm, then short of money, as it frequently was, secretly shipped twenty 2PAs to the Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun. Known in the land of the rising sun as Seversky A8Vs, these 2-seat derivatives of the P-35 performed a number of missions during the Second Sino-Japanese War which had erupted in July 1937.

Seversky Aircraft’s need to keep this perfectly legal sale off the radar was easy to understand. You see, in December 1937, Japanese warplanes had sunk a United States Navy gunboat, the U.S.S. Panay, anchored in a Chinese river port, killing three Americans. Japan’s aggressiveness toward China met with increasing hostility in the United States. If truth be told, both the United States Navy and United States Army saw the Japanese armed forces as their most likely opponent if a war was to erupt.

Sadly enough for Seversky Aircraft, The New York Times published an article in late July 1938 about the secret deal with Japan, negotiated by Miranda Brothers Incorporated, a colourful if not downright shady international trading firm, with a strong tilt toward weapons export, with the help of a dummy firm, American Trading Corporation.

For the USAAC, unhappy as it was with Seversky Aircraft, and this for a variety of reasons, from late deliveries to inadequate aircraft performance, that was the final straw. It all but refused to deal with Seversky Aircraft from then on. Unable to obtain production orders, and this at a time when the USAAC and the United States Navy were trying to order as many aircraft as they could, the company’s management came to see de Seversky as a liability, hence the April 1939 demotion, but back to our story.

Although inferior in performance to classic fighter planes like the British Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire or the German Messerschmitt Bf / Me 109, the EP-1, or J 9 as the Flygvapnet called it, was superior to any machine in its inventory.

Forty-five or so J 9s got to Sweden through Norway in 1940 before the invasion of that country brought deliveries to a stop. Another way to delivering the next batch of 15 or so aircraft was needed. Fast. While delivering the J 9s to a British port, filling their large fuel tanks right to the brim and flying them to Sweden was an option, covering close to 900 kilometres (more than 550 miles) over the North Sea in single engine, single seat aircraft with limited navigational equipment was deemed too risky.

Another option was to deliver the crated J 9s to an Italian port, Fascist Italy being neutral at the time, put the crates on one or more trains, run the trains through National Socialist Germany, transfer the crates on a ship and sail the ship to Sweden. The American government politely vetoed that rather convoluted proposal. Its British counterpart might not have been too thrilled either.

Someone finally suggested that the J 9s be shipped to Petsamo, an Arctic Ocean port city located at the northernmost tip of Finland. The Finnish, British and American governments did not object. Indeed, the Finnish government assigned one or more engineering teams to reinforce the roads and bridges between Petsamo and a Swedish port city on the Baltic Sea, 700 or so kilometres (440 or so miles) away to the south. From there, the J 9s went to a testing, repair and maintenance workshop of the Flygvapnet where they were assembled and put in service as quickly as possible.

The Finnish government had bent over backward to help its Swedish counterpart because the latter had done the very same thing when Finland was fighting for its life during its war against the USSR.

A second group of 60 J 9s never made it to Sweden, and neither did a batch of 145 or so Vultee V-48 Vanguard fighter planes, or J 10s as the Flygvapnet called these American machines, which were had been ordered in February 1940. The seizure of these 205 or so fighter planes by the American government was the result of an arms embargo the latter had decreed in early July and of a law voted in October which made possible the confiscation of as yet undelivered war supplies. The non delivery of 550 Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines was just as damaging, if not more so. And yes, the Twin Waso was one of the great aeroengines of its day.

The American government may well have thought that National Socialist Germany was on the verge of invading Sweden, a move which might well have proven successful. Mind you, the Swedish government’s decision, in June 1940, to allow large numbers of unarmed German soldiers to transit through Sweden, on their way to or from Norway, may well have raised a few eyebrows. The widescale export of iron ore to National Socialist Germany probably did not help either.

In fairness, one must admit that the Swedish government knew only too well what would happen if it really displeased its evil neighbour. It pretty much had to play nice. There was indeed no way Sweden (6.3 million people) could defeat National Socialist Germany (80 or so million people, annexed territories included).

Incidentally, the Vanguard was a machine designed expressly for export by the Vultee Aircraft Division of Aviation Manufacturing Corporation. The firm, which became Vultee Aircraft Incorporated in December 1939, actually developed a family of 4 aircraft fitted with the same wings and rear fuselage which were to fulfill both training roles (basic, intermediate and advanced) and a combat role (fighter). The basic trainer was the only member of the family to be produced in large numbers, 9 525 or so in fact. Officially known as Valiants but colloquially referred to as “Vibrators,” these aircraft were the BT-13 and BT-15 of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), the name given in June 1941 to the reorganised USAAC, and the SNV of the United States Navy, but I digress.

Once deliveries to Sweden were blocked, would you believe that the RAF thought of using a hundred or so Vultee Vanguards on Canadian soil as advanced training aircraft? However, the RAF gave up on this idea in the spring of 1941, even before taking possession of the first production aircraft. While most Vultee P-66 Vanguards, a designation adopted by the USAAF, were transferred to the Chinese air force, or Zhōnghuá Mínguó Kōngjūn, very few machines were actually used in combat against the Japanese armed forces.

Most of the 60 EP-1s confiscated by the American government found themselves in the Philippines, a commonwealth under American control at that time, in USAAF units. These obsolete aircraft, then known as P-35s, disappeared in the turmoil during the invasion of the Philippines launched in December 1941 by the same Japanese armed forces.

In any event, the American embargo and the confiscation of its war supplies put the Swedish government in a real pickle. It may well have tried to obtain German fighter planes, but that did not work. The USSR may have been approached as well but the fighter planes it might have been willing to offer were at best obsolescent. Some people have suggested that the Swedish government approached its Japanese counterpart but yours truly finds that hard to believe.

In any event, the only short-term option the Swedish government truly had access to was a request to the Italian government. The latter agreed to let the Flygförvaltningen order 60 FIAT CR.42 Falcos, or J 11s as the Flygvapnet called them, in October 1940, and this despite the fact that this fighter plane was a totally obsolete biplane.

Once assembled at a testing, repair and maintenance workshop of the Flygvapnet, in 1941, these aircraft joined the 12 Falcos initially bought by Swedish civilians in late 1939 / early 1940 as a result of a national subscription campaign aimed at providing aircraft to reinforce the Finnish air force, or Ilmavoimat, which was fighting a hopeless struggle against the overwhelmingly stronger Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily – Raboche Krestyanskaya Krasnaya Armiya, in other words the military air forces of the red army of workers and peasants. Assembled by the aircraft department of the aforementioned Götaverken, the 12 Falcos could not be delivered before the Finnish government was forced to sign a peace treaty, in March 1940. The desperately short of aircraft Flygvapnet bought the whole dozen during the summer of 1940.

The Italian government also agreed to let the Flygförvaltningen order 60 Reggiane Re 2000 Falcos, or J 20s as the Flygvapnet called them, in November 1940. That particular order was paid in cash as well as in nickel and chrome, a pair of metals the Italian war industry was always interested in.

Would you believe that the Regia Aeronautica, as the Italian air force was called back then, had chosen not to order the Falco, which explained why this rather good machine was available for export? You see, its engine was a tad unreliable and its fuel tanks leaked.

All but 2 or 4 of the J20s were shipped to Sweden by train, then by ship, and assembled there. Delivered for the most part in 1942, by which time they all but obsolete, these aircraft were nonetheless the best fighter planes in Sweden until the delivery of the first examples of a new type of fighter plane, in October 1943. While pilots liked the J 20 well enough, as long as everything worked, ground crews were rather less enthusiastic. And no, you are quite correct, my reading friend, the J 20 had not been designed to operate in a country like Sweden, where the winters could be a tad frigid.

Even so, the Flygförvaltningen seriously looked into the possibility of ordering another batch of 60 J 20s in December 1941. It had to drop the idea because Svensk Flygmotor Aktiebolaget had yet to begin mass production of the engine intended for these aircraft. In any event, the J 20s were not the only Flygvapnet aircraft that this American engine was supposed to power. But now is not the time to state how the Twin Wasp came to be produced in Sweden. Yours truly will do so next week, however.

Now, would you believe that the Re 2000 Falco and P-35 were very, very similar in appearance and size? Yea, you should. It has been suggested that Officine Meccaniche Italiane Società Anonima, as the maker of the Italian machine was known, tried to acquire the Italian production rights of the American aircraft.

Others suggest that the chief engineer of the Italian firm managed to get his hands on the drawings of the P-35 during a 2 or so year study time in the United States. Others even suggest that Seversky Aircraft and Officine Meccaniche Italiane signed some sort of secret deal which saw the latter get its hands on the drawings of the P-35. Would you believe that, according to these same others, that very deal played a role in “Sasha” de Seversky’s removal from the presidency of the company he had founded? And no, there is no evidence to the effect that the statements made in this paragraph bear any relationship to what happened, which is almost too bad, because the volume of jiggery-pokery swirling around Seversky Aircraft was deliciously mind blowing.

When we will this pontification finally reach the point when the J 22 gets mentioned, you ask? Tålamod är en dygd, my reading friend, tålamod är en dygd. Patience is a virtue. And you will have to wait until next week to learn more about the J 22. Bazinga.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)