“You know how to dry cabbage the way you do it at home?” La Société Ferdon Enregistrée / Ferdon Limitée of Laprairie / La Prairie, Québec, the first vegetable dehydration plant of the Belle Province, part 2

Welcome aboard, my reading friend! I dare to hope that all is well with you. Many people are not so lucky.

If you have no objection, yours truly would like to begin this second part of our article on the first vegetable dehydration plant in Québec with added information concerning the photograph you have just seen.

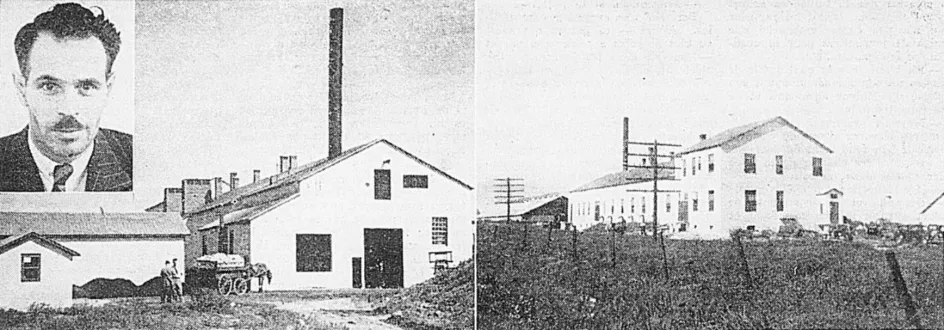

The gentleman whose photograph was / is in the upper left corner of said photograph was the managing director of Ferdon Limitée, initially La Société Ferdon Enregistrée de Laprairie / La Prairie, Québec. Before the creation of that firm, Marc H. Hudon was the general agronomist of the Société coopérative fédérée des agriculteurs de la province de Québec, the cooperative organisation which sold the bulk of the agricultural production of the province, and the head of the Service de l’industrie laitière of the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec.

What was this Ferdon, you ask, my reading friend? A good question.

That firm at the heart of this second part of our article burst onto the Québec scene, and onto the Québec press, at the very end of August 1943. The Premier of Québec and Minister of Agriculture of that province, the agronomist Joseph-Adélard Godbout, informed the press at that time that the first dehydration plant in Québec was being organised near Laprairie. As you might well imagine, this firm was La Société Ferdon.

That name was in fact a portmanteau which combined the last name of Hudon and that of the president of the firm, Raynald Ferron, a Québec agronomist, director of the Service de l’économie rurale of the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec and professor at the École supérieure de Commerce of Québec, Québec. Both Hudon and Ferron were well known to Québec’s agricultural elites. They both had quite interesting backgrounds.

Hudon, for example, began his studies in agronomy in 1921 at the École d’agriculture de Saintes, in Saintes, France, shortly before his 14th birthday. He then spent 3 years at the École supérieure d’agriculture de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, in… Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, Québec. Hudon graduated in 1925 and went to the United States at some point later on. The New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell University, a renowned American university, awarded him a master’s degree in 1928 or 1929.

Ferron, for his part, left a job in a bank to begin his agricultural studies, in 1924, at the Institut agricole d’Oka, in… Oka, Québec, an institution affiliated with the Université de Montréal, in you know where. That agronomist graduated in 1928. Ferron deepened his knowledge of rural economics at the New York State College of Agriculture in 1929-30.

Founded and managed by agronomists, La Société Ferdon aimed to be a school which would train people who knew dehydration well. Indeed, a well-equipped laboratory was located just a stone’s throw from its equally well-equipped facilities.

Construction of the facility of the firm began in July 1943, with the full cooperation of the municipal authorities of Laprairie.

As was the case with Canada’s new vegetable dehydration plants, the production tooling equipment in that facility was provided by the federal Department of Agriculture.

Subsidised by the provincial and federal governments to the tune of $75 000, or a little over $1 290 000 in 2024 currency, La Société Ferdon began processing its first vegetables (cabbage, carrots and turnips) at the end of November 1943 and...

You have a question, do you not, my reading friend? Why Laprairie and not Montréal? A good question. While it was true that Canada’s metropolis constituted an enormous potential market, it was also true that the bulk of Québec’s vegetable production came from regions located to the south and southeast of that city. Laprairie was also not far from some important railway lines. Indeed, a branch line leading to the factory of La Société Ferdon itself might, I repeat might, have been completed in 1944.

La Société Ferdon hoped to be able to process 30 or so metric tonnes (30 or so imperial tons / 33 or so American tons) of cabbage, carrots and turnips per day. For that purpose, it had an imposing cellar in the basement of its plant. The firm completed a second, even more imposing cellar in 1944.

When production began in Laprairie, all of it was destined for the federal government, which planned to ship it to Sicily and the Italian peninsula, probably to supply the Canadian Army forces participating in the invasion / liberation of Italy, in progress since September 1943.

A completely distinct dehydration plant project, in Saint-Hilaire, Québec, although envisaged around November 1943, never saw the light of day.

This being said (typed?), in December 1943, the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec joined forces with the Corporation des agronomes de la province de Québec to create a renewable scholarship on the conservation of agricultural products and, more specifically, dehydration and freezing. Part of the $6 000 allocated to that scholarship actually came from private industry. By the way, that $6 000 was worth approximately $105 000 in 2024 currency, which was a nice sum.

A young and recent (1940) graduate of the Institut agricole d’Oka and professor of horticulture for the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec was the first recipient of that scholarship, at the beginning of January 1944. Jean David spent over 4 years at the University of California, in Berkeley, California. He returned to Québec at the end of 1948 or early 1949 with a doctorate in his pocket. The Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec immediately offered him a job in its horticulture department. David became a horticultural research officer. He concentrated on the conservation of vegetable crops.

And no, yours truly does not know if the renewable scholarship on the conservation of agricultural products was awarded to someone else besides David. Sorry.

And you will never guess where David had acquired the knowledge of dehydration which might well have landed him his scholarship. Yes, yes, through an advanced training course at La Société Ferdon. In fact, while it was true that he was not part of the competition jury, the aforementioned Hudon was one of the 3 examiners. Ours is a small world, is it not?

It is so small that it is now possible for me to insert an aeronautical element into our article on La Société Ferdon in its various forms. Yes, yes, an aeronautical element. David actually took courses at the Macdonald College of McGill University before taking the train, I presume, to California. Said agricultural college of that Montréal-based university was in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Québec. It turned out that it was in that town that the Montréal Aviation Museum, a museal institution in operation since 1998, was built.

By the way, the trio of examiners also included Édouard Brochu. Did you know that this Québec agronomist / microbiologist was the co-founder, in July 1934, with the Spanish bacteriologist José María Rosell, of the Institut Rosell de bactériologie laitière Incorporée of Oka? So what, you say, my jaded reading friend? So what?! I will let you know that it was largely through Rosell, Brochu and their institute that Canada and the United States gradually discovered the benefits of yoghourt / yogourt / yoghurt / yogurt.

The word largely is very important here. You see, Quebecer Jude Delisle had actually begun to produce his Croix-Verte yogurt in a small workshop in Montréal no later than September 1931. Would you believe that he had acquired the Yoghourt trademark from the Patent and Copyright Office in April of that same year?

Aliments Delisle Limitée of Boucherville, Québec, a firm founded no later than March 1968, eventually became the largest producer of yogurt in Canada. The French multinational food firm BSN Société anonyme acquired Aliments Delisle in May 1993. The following year, BSN became Danone Société anonyme. Aliments Delisle, for its part, became Danone Incorporated in March 1997, but back to our story.

La Société Ferdon did not make much noise in 1944.

An article written by Pellerin Lagloire, an agronomist working in the Service de l’information et des recherches of the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec, published in the June issue of the Québec monthly Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, mentioned, however, that the firm planned to process 6 100 or so metric tonnes (6 000 or so imperial tons / 6 700 or so American tons) of vegetables in 1944-45.

Those very optimistic figures seemed to be realistic. Indeed, La Société Ferdon ultimately processed 4 485 or so metric tonnes (4 415 or so imperial tons / 4 945 or so American tons) of vegetables (cabbage, 47% or so of the total; turnips, 33% or so; carrots, 20% or so) in 1944, but back to our story.

In November 1944, La Société Ferdon was incorporated under the name Ferdon Limitée. Interestingly, neither Ferron nor Hudon were part of the group of 5 people from Montréal, that is 1 notary, 2 accountants and 2 stenographers, who carried out that work.

The firm might, I repeat might, have counted on a good 100 or so male and female employees. Its workforce actually included a high percentage of women from the Laprairie region. Mind you, most of its male employees presumably came from that same region.

The vegetables processed by Ferdon came partly from a farm of just under 50 hectares (120 or so acres) in Sainte-Clothilde-de-Châteauguay, Québec, which it owned. Those excellent lands being insufficient for the task, the firm also called on 200 or so farmers located at a maximum of 16 or so kilometers (10 or so miles) from its factory. Trucks transported 85% or so of the vegetables intended for Ferdon. The rest travelled to the factory in horse-drawn carriages, I think.

The dehydration of vegetables began in July 1944, with the arrival of the first cabbage. That work continues until December. Carrots, for their part, were processed in December and January. Turnips brought up the rear. They were processed from January to April. And yes, the Ferdon plant might have been inactive every year from mid-April to mid-July.

As 1945 began, Ferdon’s management planned to increase its product range, adding spinach, onions, etc. It planned to process fruits such as pumpkins, blueberries, etc. And yes, again, the pumpkin is well and truly a fruit.

Let me point out here that Ferdon might, I repeat might, have dehydrated some quantity of rutabaga / swede, a root vegetable also known in Québec as choutiame / chouquiame, two terms which quite possibly drive bonkers the good people of the Office québécois de la langue française, an organisation informally known as the language police.

Yours truly will teach you nothing by telling you that the dehydrated vegetables produced by Ferdon represented only a very small percentage of the production capacity of the 12 to 15 Canadian factories in operation around 1944-45.

Would you believe that in 1945 alone and for the British market alone, those factories produced just over 5 400 metric tonnes (5 325 or so imperial tons / 5 960 or so American tons) of dehydrated vegetables (turnips, spinach, potatoes, onions, carrots, cabbage and beets)? Potatoes alone represented about 75% of that production. Spinach, for its part, represented 0.035% of that production.

Yours truly cannot say if the British did not like that vegetable plant originating from Iran, yes, yes, Iran, or if Canadians liked it so much that they wished to keep all the production in the country. A well known American, Mathurin / Popeye the sailor man, must have been a tad annoyed by that possible wish.

Yes, yes, Mathurin. It was under that name that this great spinach chomper before the lord was initially known in France and Québec during the 1930s.

A brief digression, if I may. My maternal grandfather, a dour pater familias that I never saw smile, was rather fond of Popoyee, his personal pronunciation of the name of that famous American sailor. Whether he discovered Popeye in a newspaper or local movie house, in the 1930s, 1940s or 1950s, I cannot say.

And yes, my reading friend who wants to return to the subject of the day, dehydrated vegetables intended for the British market constituted a significant part of the Canadian vegetable production.

Would you like to see some photographs related to Ferdon’s activities? […] Wunderbar!

The second cellar of Ferdon Limitée of Laprairie, Québec. That building was then the largest cellar on Québec soil. Eugène Stucker, “Nouvelle industrie du Québec : La déshydratation des légumes.” Technique, March 1945, 207.

The first phases of the vegetable dehydration process in the Ferdon Limitée factory in Laprairie, Québec: the washing of the vegetables, here cabbage, in a rotating tank, and a first examination. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 9.

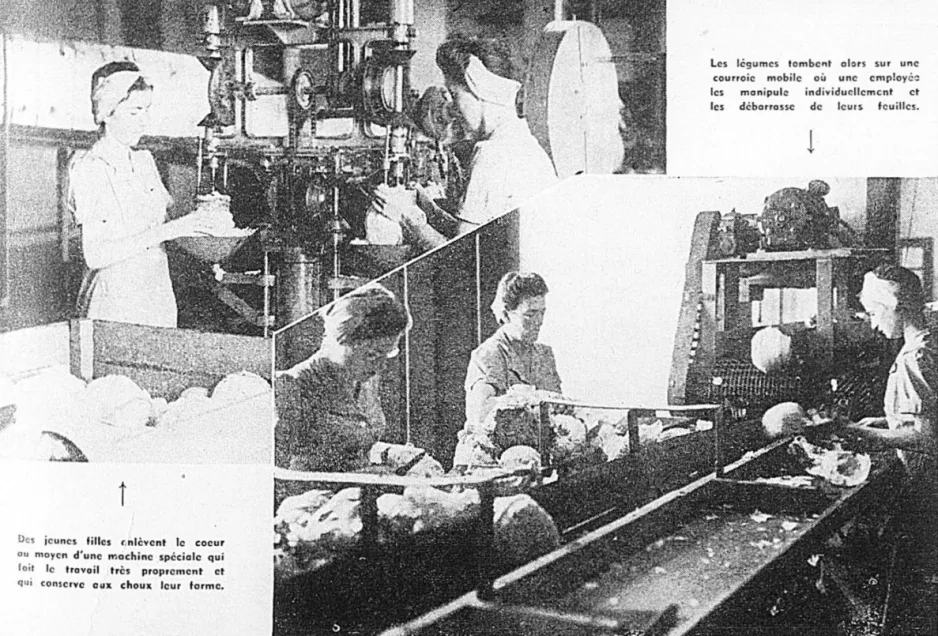

Two subsequent phases of the dehydration process of our cabbage: removal of the cores, on the one hand, and of spots and dead leaves on the other. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 9.

Two other phases of the dehydration process of our cabbage: chopping those vegetables into thin strips on the one hand and, on the other, spreading the chopped cabbage in thin uniform layers on racks. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 10.

Before being placed on racks, however, the chopped cabbage passed through a sulphite bath whose aim was to preserve their color and nutritional value. Eugène Stucker, “Nouvelle industrie du Québec : La déshydratation des légumes.” Technique, March 1945, 209.

Entrance of the racks filled with chopped cabbage into the dehydration tunnel. Eugène Stucker, “Nouvelle industrie du Québec : La déshydratation des légumes.” Technique, March 1945, 210.

Exit of the racks filled with chopped dehydrated cabbage from the dehydration tunnel. Eugène Stucker, “Nouvelle industrie du Québec : La déshydratation des légumes.” Technique, March 1945, 211.

Filling metal cans with dehydrated cabbage, left, and weighing one of these metal cans before its lid was sealed. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 11.

Manual pressing of the dehydrated cabbage into in their metal boxes using pestles, while said boxes were gently shaken mechanically, to help the process. Eugène Stucker, “Nouvelle industrie du Québec : La déshydratation des légumes.” Technique, March 1945, 212.

Replacement of the air contained in metal boxes containing approximately 4.5 kilogrammes (10 pounds) of dehydrated cabbage with an inert gas (nitrogen?), in order to ensure their preservation, on the left, and crimping of the lid of one of the boxes in question. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 11.

The female technician at the Ferdon Limitée laboratory in Laprairie, Québec, performing various tests. J.B. Roy, “La déshydratation des légumes.” Le Bulletin des Agriculteurs, January 1946, 11.

The official end of the Second World War, in September 1945, and the subsequent cancellation of military contracts dealt a severe blow to the Canadian dehydration industry. Even the British Ministry of Food got into the act by canceling at the end of 1945 orders placed in 1944 and / or 1945.

In June 1945, for example, that ministry had ordered 8 750 or so metric tonnes (8 625 or so imperial tons / 9 650 or so American tons) of dehydrated vegetables (turnips, potatoes, carrots, cabbage and beets).

There were obviously significant layoffs. One only needed to think of the 1 500 or so people laid off toward the end of 1945 by Canada Foods Limited of Kentville, Nova Scotia, Island Foods Incorporated of Summerside, Prince Edward Island, Pirie Potato Products Limited of Grand Falls, New Brunswick, and another firm in the Atlantic provinces.

Canada Foods and New Brunswick Potato Products Limited of Hartland, New Brunswick, reopened their doors in January 1946, however, if only temporarily. You see, at least one of those firms was ordered to reopen in order to complete its contract with the Ministry of Food. And yes, other firms might also have reopened elsewhere in Canada to complete their own contracts. Even so, the future of the Canadian dehydration industry was far from rosy.

It went without saying that the obvious lack of interest in dehydrated foods from the United Nations Relief and Reconstruction Administration, an organisation active in many countries in Asia (Korea and China) and Europe (Yugoslavia, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Poland, Greece, Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria), did not improve things.

You see, while some observers had predicted (hoped for?) a singing tomorrow once peace returned, the fact was that the typical Québec or Canadian family was more interested in frozen foods than dehydrated foods. Dehydrated foods ultimately only had a tiny place in the menu of such a family.

Nor should one have relied on the British market. Indeed, a scientific advisor to the Ministry of Food, the English biochemist Jack Cecil Drummond, had stated as early as November 1943 that dehydrated foods would only hold a tiny place in the menu of a typical British family once peace returned. That assertion was quickly confirmed once said peace returned.

Mind you, a few dispatches published in the United Kingdom in July 1944 may not have added to the prestige of dehydrated foods.

In a (serious?) speech delivered to the Honorable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in Parliament assembled, during a debate on Scottish agriculture, a very popular Scottish Member of Parliament from the Labour Party, Alexander “Sanny” Sloan, claimed that, as the best cuts of meat produced in Scotland were being exported, dehydrated frogs had to be imported in order to feed the population.

“Did my honourable friend say frogs,” asked an incredulous and somewhat stunned Member of Parliament from the Conservative and Unionist Party, the Under-Secretary of State for Scotland, Henry James Scrymgeour-Wedderburn, Earl of Dundee? “Yes, frogs,” replied Sloan, “but I won’t give you my authority for it. You might as well have dehydrated bugs as dehydrated eggs from China and America.”

Yours truly assumes that this exchange with some racist connotations caused a certain hilarity within the Honorable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in Parliament assembled.

I would be remiss if I did not mention at this point a July 1944 humorous poem by Ferlie Moudiewort, a fictional proletarian poet created by Gangrel, the pen name of Scottish author Harold S. Stewart for his occasional column Bats in the Belfry, published in a major Scottish daily newspaper, Daily Record and Mail. And yes, said poem came out after the speech, not before it.

Untranslatable is not French, you affirm, my emphatic reading friend, thus paraphrasing a sentence attributed to a megalomaniacal tyrant? Yes, yes, Emperor Napoléon Ier, born Napoleone di Buonaparte, but I digress.

Brilliant as you are, you will obviously have no difficulty in deciphering said poem:

I’ve et some queerish things, frae craws

Tae robins (whilk some fowk ca’ ruddocks);

But never, kennin’, hae my jaws

Been used on dehydrated puddocks.

I’ve spent, on mony an unco’ dish,

My shillin’s (sometimes kent as scuddicks);

I’ve taen a chance wi’ fowl and fish,

But no’, I think with poothered puddicks.

So, is that decipherment coming or what? I have to continue this peroration, you know.

Allow me also to mention the following comment, also published in July 1944 by Daily Record and Mail: “Tasted your dehydrated frog yet? No? Try our savoury croakettes.” Ba dom tss. End of digression.

Sadly enough, the then inactive vegetable dehydration plant of Pirie Potato Products was destroyed by fire in August 1946. In turn, the only plant active in the Atlantic provinces at the time, that operated by New Brunswick Potato Products, was destroyed by fire in October. The paper mill operated in St. George, New Brunswick, by St. George Pulp & Paper Company Limited, in turn, had been similarly destroyed less than a week earlier.

One wonders if those disasters were coincidences, or if they were related to the many wildfires which devastated the province in the summer and fall of 1946. In any event, New Brunswick was one very unlucky place that year, but back to dehydration in Québec and Ferdon.

The creation of other vegetable dehydration plants on Québec soil once the Second World War was over did not go beyond the stage of predictions or hope.

In January 1946, around 50 people worked in the Ferdon factory. And yes, that workforce still had a high percentage of women. That staff was divided into 2 teams. The day shift lasted 11 hours. The night shift shifts lasted 11.5 hours for women and 12 hours for men. Ow!

Yours truly cannot say whether that staff worked 6 or 5 days a week. And no, I very much doubt that those people were unionised.

As 1946 began, Ferdon had around 225 market gardeners under contract. Those were able to supply it with a little over 25 hectares (a little over 65 acres) of turnips, a little over 40 hectares (105 or so acres) of carrots and a little over 100 hectares (a little over of 250 acres) of cabbage. Ferdon’s aforementioned farm could then count on a little less than 70 hectares (a little less than 170 acres) of good land. Only 15 or so hectares (less than 40 acres) were under cultivation then, however.

It should be noted that Ferdon provided seeds and insecticides to its producers. Its staff also provided advice to members of that group who requested it.

Better yet, Ferdon paid its suppliers at the end of the month in which they had delivered their vegetables – a unique case in Québec, or even in Canada, at the time, it was said. That regularity, combined with the prices per unit of measurement paid, ensured the reputation of the firm.

Ferdon’s reputation was so good within the dehydration industry that Hudon had the honour of becoming the founding president of the Canadian Dehydrators’ Association, founded in Montréal in January 1946 by representatives of 11 firms established in 7 of the 9 provinces of Canada. Yes, only 7 of the 9. No representative from Alberta or Saskatchewan showed up in Montréal.

And yes, Hudon was the only French-speaking member of the steering committee of the Canadian Dehydrators’ Association, an organisation which did not seem to have functioned for very long. Indeed, Hudon did not remain at the head of that association for very long anyway.

You see, Heeney Frosted Foods Limited of Ottawa, Ontario, acquired the Ferdon plant in late March, early April 1946. That firm which pioneered food freezing in Canada quickly transformed its new industrial site into a quick-freezing plant.

In 1952, for example, the plant produced 1 055 or so metric tonnes (1 040 or so imperial tons / 1 160 or so American tons) of frozen vegetables (spinach, green peas, maize / corn and beans) and 55 or so metric tonnes (55 or so imperial tons / 60 or so American tons) of frozen strawberries. It also produced some frozen fish during the 1950s.

In June 1962, a violent fire destroyed the Laprairie plant of Heeney Frosted Foods, a subsidiary since 1959 of Czarnikow Canada Limited, I think, itself a subsidiary of the English sugar brokerage firm C. Czarnikow & Company.

In December 1946, the head office of Ferdon, of the ghost of Ferdon in fact, had moved to Dunham, Québec, where its president now resided. No, not Ferron, Hudon.

Ferdon abandoned its charter and was wiped off the map in January 1951.

At that time and in the following years, Hudon lived in Dunham and took care of his farm and orchard. Indeed, he was active within the Quebec Apple Growers Cooperative and the Société pomologique et de culture fruitière de la Province de Québec. Mind you, Hudon also devoted part of his time to the management of Hudon & Orsali Limitée of Montréal, one of the most important wholesale grocery businesses in Québec.

The aforementioned Ferron did not suffer from the sale of Ferdon to Heeney Frosted Foods either. Then deputy director of services at the Ministère de l’Agriculture du Québec, he became the treasurer of the Société coopérative fédérée des agriculteurs de la province de Québec no later than early 1949.

And this is how this issue of our breathtaking blog / bulletin / thingee ends.

And your decipherment of Ferlie Moudiewort’s poem, is it for today or tomorrow?

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)