As the world, err, as the wheel turns; Or, How / why SS Klondike, a cargo-carrying sternwheeler river boat briefly used for river cruises, became one of Parks Canada’s 1,004 national historic sites, part 1

Are you one of those people who dream of cruising a lonely sea, with a star to steer your ship by, my reading friend, if I may ineloquently paraphrase a teeny tiny bit of the superb poem Sea-Fever, published in 1902 in the first volume of poetry put out by famous English poet and writer John Edward Masefield? Yes? Good for you. I am very much a unadventurous landlubber, I am afraid.

Still, yours truly would like to launch a nautical topic on this fine day of May. The proven usefulness of taking baby steps before jumping off a cliff being a watchword of my existence, the topic of this issue of our white-sailed blog / bulletin / thingee will touch upon a ship which never sailed a lonely sea, or a busy one for that matter. Nay. The ship in question sailed one of the many great waterways of Canada. That story began a long time ago.

In the early summer of 1896, in the Northwest Territories, 240 or so kilometres (150 or so miles) south of the Arctic Circle, a Canadian gold digger, Robert Henderson, discovered an interesting site near a stream which flowed into the Klondike River, a tributary of the Yukon River. As was customary, he informed gold diggers who crossed his path. One of these, an American by the name of George Washington Carmack, settled on a nearby stream, Rabbit Creek, with his spouse, her brother and their nephew, all three of them members of the Tagish nation. On 16 August 1896, one of these people saw an object shining in the bottom of the water: GOLD! The news spread like wildfire. The few hundred gold diggers in the area soon flocked to the site, soon renamed Bonanza Creek.

Realising what was happening, Joseph Francis “James / Joe” Ladue, born Joseph Ledoux, an American prospector and trader, purchased land at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers, approximately 15 kilometres (approximately 10 miles) from the site of the initial gold discovery. He thus delimited the site of a small town quickly baptised Dawson City, or plain Dawson.

The Klondike, as the region became known, was so isolated that the discovery of the gold sites remained unknown to the outside world until shortly after mid-July 1897, with the arrival in Seattle, Washington, and San Francisco, California, of two ships carrying gold and gold prospectors who had made their fortune the year before. A gold rush began which reached its climax in 1898. The impact of the discovery was all the more important since at that time much of the Western world was still suffering the effects of a quarter of a century of economic stagnation.

More than 100 000 people from all corners of the globe, mostly white men, set off for the Klondike. Many gave up along the way. Those who arrived in the Territory of Alaska, the final destination for ships arriving from everywhere, found themselves confronted with formidable obstacles: a very rough terrain and a ferocious climate. Barely 40 000 people, including more than 30 000 Americans, made it to Dawson City. Worse still, barely a few hundred of these people found a good vein.

In any event, Dawson City became for a time, from the summer of 1898 to the spring of 1899, the largest North American city west of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and north of San Francisco. The population of that Paris of the North, as it was called, went from 4 000 in June 1897 to 25 000 in June 1898. There were buildings with central heating, churches of four denominations, cinemas, two daily newspapers, four-star restaurants and upscale stores showcasing the latest creations of Parisian fashion.

By 1900, residents had at their disposal all the services of a southern city: running water, sewers, an electrical power grid and a telephone network. Indeed, Dawson City’s power grid was second to none in Western Canada. By then, however, the city only had 5 400 residents. That fall could be explained by the announcement, during the winter of 1898-99, of the discovery of gold deposits in Nome, Territory of Alaska, in July 1898.

Although greatly reduced in importance, Dawson City continued to play a vital role in the development of the Yukon Territory. Indeed, that municipality was the capital of that territory.

In turn, the Yukon River continued to play a vital role in the transportation system of the Yukon Territory. Shallow draught sternwheeler river boats were the primary mode of transportation with the outside world. Up to 250 river boats plied the waters of the Yukon River, all 755 or so kilometres (470 or so miles) of them, between White Horse, Yukon Territory, and Dawson City, transporting mainly cargo but also some people for as long as the river remained passable.

The introduction of bushplanes in the regions of White Horse (1927) and Dawson City (1935), slowly began to reduce the importance of the river boats. The inauguration of a road to Dawson City, in 1952, I think, was all but a death knell for those workhorses. It was in that changing world that the ship at the heart of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee hit the waves.

One could argue that our story began in June 1936, when the large sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike, then on its way to Dawson City, foundered in a matter of minutes when treacherous currents rammed it into an rocky ledge rock of the Yukon River, 145 or so kilometres (90 or so miles) north of White Horse. Every passenger and crew member were able to escape in the steamer’s lifeboats but two horses stored below deck could not be reached as the ship drifted downstream over a distance of 5 or so kilometres (3 or so miles). Its hull ripped open, SS Klondike ended up wedged on a sandbar, with only its upper deck piercing the swirling waters of the Yukon River.

SS Klondike was operated by the river division of White Pass & Yukon Railway Company Limited of London, England, I think. Mind you, yours truly wonders if the river division of that firm was not in fact British Yukon Navigation Company Limited of White Horse. In any event, as of 2023, the remains of SS Klondike were still visible just below surface, or just above it, when water levels are low.

The very size of SS Klondike meant that White Pass & Yukon Railway quickly chose to order a nearly identical replacement vessel. That order was given to its subsidiary, British Yukon Navigation. Construction began no later than August 1936. To save time and moolah, White Pass & Yukon Railway and / or British Yukon Navigation salvaged the steam engines and boiler of SS Klondike, not to mention many fittings.

Incidentally, said nearly identical replacement vessel would be called... SS Klondike.

By the way, did you know that the boiler of SS Klondike was a locomotive boiler made in 1909 by Polson Iron Works Limited, a shipbuilder and maker of steam engines based in Toronto, Ontario?

So what, you ask, my blasé reading friend? So what!? I will let you know that Polson Iron Works played an interesting and quite important role in the history of Canadian shipbuilding. That firm built the first Canadian steel ship, SS Manitoba, completed in 1889 for Canadian Pacific Railway Company of Montréal, Québec, a Canadian transportation giant mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since April 2018. It also built the first Canadian armed ship, CGS Vigilant, completed in 1904 for the Department of Marine and Fisheries.

Mind you, in 1897, Polson Iron Works had completed one of the oddest and most inefficient ships on all time, the Roller Boat, imagined by Prescott, Ontario, lawyer and inventor Frederick Augustus Knapp. The co-imaginator and co-financier of that cylindrical vessel, sometimes known as Knapp’s Folly, was the well-known late 19th and early 20th century American Canadian funambulist / inventor / entertainment promoter William Leonard Hunt, also known as Guillermo Antonio Farini but better known as The Great Farini.

Yours truly also wishes to point out that Polson Iron Works made a brief foray in the world of aviation during the First World War. Yea, it did. You see, my reading friend, the president and general manager that firm, John Bellamy Miller, came to believe that aviation was a field of work worth looking into. In late 1915 or early 1916, he seemingly got in touch with a small, short lived and poorly known American firm, Steel Constructed Aeroplanes Company, an initiative which seemingly led to the creation of another small, short lived and poorly known American firm, MFP Aero Sales Corporation. And yes, the M in MFP stood for Miller.

And no, the P in MFP did not stand for Polson. Nay. It stood for Walter H. Phipps, an American designer of aeroplanes and… model aeroplanes.

All of these contacts resulted in the development of a family of 4 military biplanes which could be flown with wheels or floats, as required, with a fabric-covered structure made from wood and steel, which was a tad unusual for the time, especially in North America.

The prototype of a 2-seat biplane, the MFP Model B, made by Polson Iron Works, flew in March 1916, in Toronto. It was later shipped to the United States where representatives of the Koninklijke Marine and Regia Marina, in other words representatives of the navies of the Netherlands and Italy, watched it fly. Oddly enough, the Model B was seemingly not officially offered to the governments of the United States, United Kingdom or Canada.

No other member of the MFP family of aircraft was made, either in Canada or the United States.

One of the individuals who went to Toronto in 1916 to train the staff of Polson Iron Works in the art of aeroplane manufacturing went by the name Jean Alfred Roché. In 1929, Aeronautical Corporation of America (Aeronca) bought the rights to produce a small aircraft developed in 1925 by that Franco American aeronautical engineer. Once modified / updated, that aircraft became the Aeronca C-2, the first truly successful North American light / private plane. It should be noted that the mind blowing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, located in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a C-2.

You did not think that the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, a glorious institution if there was ever one, would be mentioned in this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, now did you? As was pointed out in the past, given that there is most certainly a will on my part to mention that incomparable museal institution as often as (in)humanly possible, you can bet your knickers that I will do my very best to find a way to do it, but back to SS Klondike.

Launched in the spring of 1937 and in service by June at the latest, the wood-burning SS Klondike performed splendidly over the following years, initially as a (silver carrying?) mining freighter.

The outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1939, negatively impacted the price of silver, which negatively impacted the amount of silver carried on the Yukon River. The early to mid 1940s were therefore lean years for British Yukon Navigation. SS Klondike actually spent an entire navigation season on shore, on the ways of the firm’s White Horse shipyard.

Mind you, SS Klondike also contributed to Canada’s war effort in a more direct manner. One particular year, it transported cargo and personnel to help with the construction of the Alaska-Canadian Highway, between Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and Delta Junction, Territory of Alaska, a strategically important roadway which linked said Territory of Alaska and Yukon Territory to the rest of North America.

An increase in silver and lead production in the late 1940s helped balance British Yukon Navigation’s books – and returned SS Klondike to regular service. Indeed, extra staterooms were added in 1945. They were followed by a bar and lounge, in 1952, I think.

The opening of a North-South all season road between White Horse and Mayo, Yukon Territory, in 1950, brought to a close SS Klondike’s career as an ore carrier. The ship continued to ply the waters of the Yukon River, however, carrying both freight and passengers.

Travelling back and forth on the Yukon River was no picnic. No siree. Some tracts of that waterway were quite shallow, with only 15 or so centimetres (6 inches) of water between the riverbed and the flat bottom of SS Klondike. In other locations, the river’s navigable channel was barely 18 metres (60 feet) wide, a dangerously narrow path for a 12 metre (40 feet) wide ship. Given such challenges, it came as no surprise that a river pilot interested in obtaining his own command would not be considered until he had 15 or more years experience under his belt.

As was said (typed?) above, the inauguration of a road / highway to Dawson City, in 1952, I think, was all but a death knell for the sternwheeler river boats which were still plying the waters of the Yukon River. Indeed, SS Klondike itself was seemingly taken out of service in 1952 but fear not, my reading friend. All was not lost.

Incidentally, the seat of the government of the Yukon Territory moved from Dawson City to White Horse in April 1953. That move was to a large extent motivated by the greater demographic weight of the latter community, as well as the completion of a road / highway between Dawson and White Horse, but back to SS Klondike. Again.

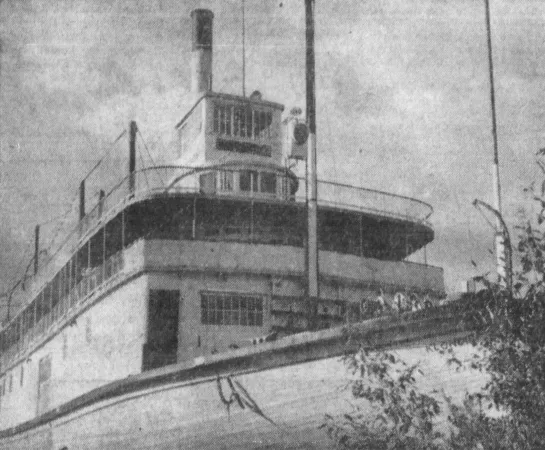

The reconstructed Canadian sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike at the time of its first cruise on the Yukon River, from White Horse, Yukon Territory, to Dawson City, Yukon Territory. Charlie King, “Leisurely Days Back As Klondike Starts Life Again.” The Vancouver Province, 22 June 1954, 3.

At some point between 1952 and 1954, in 1953 perhaps, the management of Canadian Pacific Airlines Limited of Vancouver, British Columbia, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway, contacted its counterpart at White Pass & Yukon Corporation of Vancouver, the new corporate identity of White Pass & Yukon Railway, acquired in October 1951 when Canadian interests took over the firm.

Need yours truly add that Canadian Pacific Airlines was mentioned moult times in our interstellar blog / bulletin / thingee since May 2019? I thought not.

The gaudy mural in the lounge of SS Klondike with its high kicking dancing girls. John D. McOrmond, an employee of T. Eaton Company Limited, on the left, supervised the interior decoration of the ship. SS Klondike’s commanding officer, William J. “Bill” Bromley, was with him when the photograph was taken. Charlie King, “Rebirth of the North – ‘Commodore’ Of Fleet Pumps Gas All Winter.” The Vancouver Province, 23 June 1954, 3.

The good people of Canadian Pacific Airlines had a plan, and what a plan it was. They would finance a reconstruction of SS Klondike which would transform that very ordinary river boat into a luxurious cruise ship fitted with a swanky lounge with a dance floor, full bar facilities and a high tech radio and record playing system. There would even be an observation parlour finished in mid-Victorian style. The ship would accommodate up to 50 passengers on two decks, in 25 staterooms fitted with foam rubber mattresses as well as hot and cold water.

Incidentally, the person overseeing the interior design of the ship was an employee of T. Eaton Company Limited, one of the largest department store chains in Canada and a firm mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since January 2019. He was called John D. McOrmond.

The reconstruction of SS Klondike might have cost $100 000, roughly $1 075 000 in 2023 currency, if not more, something like 40 to 50% more perhaps.

Did said reconstruction include a switch from wood to oil as a fuel, you ask, my technically astute reading friend? Nay, it did not. That switch was apparently performed around 1952.

Incidentally, each and every bottle of beer sold at the ship’s bar would have to come from outside. At 75 cents a pop, or approximately $8.20 in 2023 currency, they would not exactly be cheap.

Now, do not get me wrong, yours truly has paid and will continue to pay that kind of money for a beer, but it better be good. I distinctly remember paying almost twice that sum for a 330 millilitre (11.6 Imperial fluid ounces / 11.2 American fluid ounces) bottle of Brouwerij de Molen’s Kopi Loewak, an extra strong (11.2% alcohol) coffee stout from the Netherlands. That must have been 10 to 15 years ago. A very nice beer. Sadly enough, it is no longer being brewed.

Incidentally, again, the term kopi luwak refers to a coffee made from coffee cherries which had been eaten, partially digested, fermented and, err, defecated by a cat like critter known as the Asian palm civet. I kid you not. That unique product was first consumed by 19th century Dutch coffee planters / occupiers / exploiters / colonisers in what were then the Nederlandsch-Indië, today’s Indonesia.

Understandably enough, kopi luwak was the most exclusive and expensive coffee in the world until Black ivory coffee came along, around 2012, that is. And yes, you are quite correct, my slightly nauseous reading friend, that new delicacy of delicacies was / is, err, processed by 20 or so Asian elephants living in Thailand. End of ciceronian digression and… Sigh… A cicerone is a beer sommelier. You should go out more often, my homebody reading friend, but back to our story.

Canadian Pacific Airlines thought / hoped that tourists flown from Vancouver or Edmonton, Alberta, to White Horse aboard one of its aircraft would be fascinated by the idea of cruising to the site of the famous Klondike gold rush. Those Klondike Tours, as the airline called those package tours, were to some extent aimed at American tourists. Oh, before I forget, the price mentioned in American newspapers was $390 for an 8 day package tour, which corresponds to approximately $5 900 in 2023 Canadian currency. Per person. Of course.

Before I forget, the aircraft used by Canadian Pacific Airlines might well have been Convair Model 240s, older cousins of the Convair Model 580 remote sensing aircraft of the unforgettable Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike as it plied the waters of the Yukon River during one of its 1954 cruises between White Horse, Yukon Territory, and Dawson City, Yukon Territory. Anon., “Not too rugged.” Fort Lauderdale Sunday News, 10 April 1955, 13-D.

The sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike going through one of the tricky stretches of the Yukon River during one of its (1954?) cruises between White Horse, Yukon Territory, and Dawson City, Yukon Territory. Anon., “Sternwheeler to Sourdough Country.” The Ottawa Citizen – Weekend Magazine, 25 June 1955, 1.

Now chartered by Canadian Pacific Airlines, SS Klondike began its new career in June 1954. Travelling down the Yukon River, from White Horse to Dawson City, took approximately 40 hours. The journey back, made possible in one location, the formidable Five Finger Rapids, by a powerful winch and underwater cable picked up by the crew on every trip, took approximately 130 hours.

The sternwheeler river boat SS Klondike moored on the Yukon River during one of its (1954?) cruises between White Horse, Yukon Territory, and Dawson City, Yukon Territory. One of its passengers, Bruce West, a columnist with a Toronto, Ontario, daily newspaper, The Globe and Mail, perhaps, is panning for gold in the foreground. Anon., “–.” The Detroit Free Press, 7 August 1955, 23.

The good folks onboard who did not like to dance could watch the scenery, visit abandoned gold mine sites or Indigenous camp sites, play shuffleboard, pan for gold, catch some fish, etc., etc., and they could do all that for a long time. As we both know, regions north of White Horse experienced at least 15 hours of daylight between mid April and mid August.

Quite shockingly, Indigenous cemeteries were also visited on some occasions.

Despite the absence of docking facilities, going ashore was seemingly not a problem. SS Klondike’s captain simply brought the prow of his shallow draught ship into the wooded shore of the Yukon River. Some crew members then lashed a cable to a large tree. Easy-peasy.

By the way, if one was to believe John Tomlinson, the teenage son of a British Yukon Navigation economist living in White Horse who was hired in 1954 as a dishwasher and cabin boy, a member of the crew, possibly, and I do mean possibly the purser, err, “salted” a few of the spots where panning took place.

Mind you, on at least one occasion, a ginormous if thoroughly fake / bogus nugget caused a great deal of hilarity among both passengers and crew. Can you guess the name of the happy person who found that nugget, in 1954 or 1955, my smarty pants reading friend? No? Oh, oh, somebody has got a frowny face. All right, all right. Said happy person was Bruce West, a columnist with an influential Toronto, Ontario, daily newspaper, The Globe and Mail.

The ginormous and thoroughly fake / bogus gold nugget found (in 1954?) by an SS Klondike passenger, Bruce West, a columnist with a Toronto, Ontario, daily newspaper, The Globe and Mail, Isaac Creek, Yukon Territory. David Willock, “There’s Tourist Gold in the Yukon.” The Ottawa Citizen – Weekend Magazine, 25 June 1955, 19.

Incidentally, SS Klondike’s captain was William J. “Bill” Bromley, commodore of the British Yukon Navigation fleet. He occupied that high status position only during the summer months, however. Bromley had spent the winter of 1953-54, and that of previous years, pumping gasoline at a service station located in Victoria, British Columbia. Indeed, Bromley had been living that double life, a few months up north on river boats and many months down south filling various positions, since 1923.

And yes, a person or couple booking a trip on SS Klondike would go down the Yukon River from White Horse to Dawson City before making the journey back. The package tours lasted 8 days.

Canadian Pacific Airlines planned to make a trip every 9 days for a grand total of 10 trips during the summer of 1954. If that trial run proved popular, and presumably profitable, one or more of the 5 other sternwheeler river boats stored on ways at White Horse might undergo a similar reconstruction before setting out on a new career as cruise ships.

Do I have you at the edge of your seat, my reading friend? Do you wish to know more? Too bad, so sad. You will have to wait until next week. Bwa, ha, ha. Sorry, sorry.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)