Don’t let it be forgot that once there was a firm, for one brief shining moment, that was known as La Machine Agricole Nationale Limitée of Montmagny, Québec

As you may have noticed, I hope, my reading friend, our blog / bulletin / thingee regularly opens its columns to topics of an agricultural or food nature. Yours truly will not derogate from this rule in this month of June 2021. Thus, I hereby and heretofore offer you a peroration on a firm whose history was a brief and shining moment in the great adventure of the agricultural machinery industry of Québec / Canada. I hope once again that this text will be an exercise in minimising sesquipedalian loquaciousness. (Hello, EP!)

Captivating and dramatic music behind the scenes. The curtain opens. It was March 1871, in Montmagny, Québec, a small town on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. Arthur Napoléon Normand was born. His childhood resembled that of many other young Quebecers of his generation.

In 1893, Normand founded a small firm, Montmagny Machine Works (Registered?), perhaps located in the village of Saint-Thomas-de-la-Pointe-à-la-Caille, 3 steps from Montmagny, which produced wood sawing machines and threshing mills intended for the local / regional market.

Working together with 8 other people (1 baker, 1 bottler, 1 farmer, 1 lawyer, 3 merchants and 1 navigator), Normand founded the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny in 1902. He was the manager of this firm, apparently also located in Saint-Thomas-de-la-Pointe-à-la-Caille, whose staff built, among other things, steam and gasoline engines.

The Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny factory was virtually destroyed by fire in early December 1902. Just six months later, another fire ravaged the building. Although severely shaken, Normand and his staff put the firm back on its feet on both occasions.

Weeks, months went by. Business looked good. In fact, at the end of May 1906, Normand tested his “gasoline yacht” on the St. Lawrence River. It should be noted in passing that the engines, if not the entirety of said yacht, were produced in the shops of the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny. Normand apparently bought himself a second and magnificent “gasoline yacht,” completed around June 1907.

A brief digression if I may. In April 1906, the Compagnie Charles-A. Paquet of Québec, Québec, a firm which sold accessories, hardware and machinery founded by Joseph Henri Paquet and Joseph Charles Abraham Paquet, brothers and merchants of Québec, ordered (from the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny??) equipment (vehicles?) used for the construction of roads. Would it be indelicate to mention that the latter Paquet was well known to the party in power in Québec? Said party had a somewhat… liberal attitude when it came to helping its friends and allies.

This being said (typed?), the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny seemingly did not really took off until around 1911, when it landed (new?) contracts for the production of equipment for road construction. The purchase of said equipment may very well have been linked to the subsidies granted by the ministère de l’Agriculture of Québec from that same year 1911 onward, via the Loi des bons chemins, for the purposes of graveling, paving and improving the main road of villages, as well as their maintenance.

The contracts won by the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny very possibly came from the Compagnie Charles-A. Paquet. These contracts were of such magnitude that the investments necessary to carry them out jeopardised the financial stability of the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny. The firm was in dire need of money.

Normand therefore joined forces with a few people to found Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries Limitée in Montmagny, in October 1912. And yes, 2 of the 4 people in question were the Paquet brothers.

Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries, a firm with a varied mandate to say the least, took control of the assets of the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny in December 1912. It also absorbed the Compagnie Charles-A. Paquet.

Acting with the blessing of the shareholders, Normand dissolved the Compagnie manufacturière de Montmagny around October 1913. This being said (typed?), the main shareholder and directing soul of Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries was indeed the businessman Joseph Charles Abraham Paquet.

The latter was born in March 1868 in Québec. Like his father, he went into the retail business. In 1891-92, Paquet sold milk and flour. In 1898, he was the agent of Canadian Dairy Supply Company of Montréal, Québec, for the Québec region. In 1900-01, Paquet began selling equipment for butter factories.

Paquet was one of the (15?) investors who, in May 1901, launched the Compagnie de pulpe de Métabetchouan – one of the first pulp producers in the Lac Saint-Jean region of Québec. A new phase of his life began. The aforementioned Compagnie Charles-A. Paquet was born in September 1902, for example, but back to our story.

Wishing to increase the well-being of his staff, or his control over it, Paquet bought many plots of land in Montmagny and Saint-Thomas-de-la-Pointe-à-la-Caille that he wanted to transform into a neighbourhood reserved for said staff. In 1913, he supervised the division of these lots and the opening of streets. This project did not appeal to everyone, however. Indeed, it was not until 1916 that Paquet finally conquered or convinced his last opponents. The sale of the lots could thus begin. Paquet, Normand and 3 other people founded the Compagnie de Construction de Montmagny in June to build the houses in the new neighbourhood.

In 1918 or 1919, Paquet joined the group of investors which, in April 1918, had created the Corporation d’énergie de Montmagny – the first electricity transmission and distribution firm in the Montmagny region. Would you believe that the first client of this firm based in Québec until March 1919 was La Machine Agricole Nationale Limitée of Montmagny, and ... Oh, yours truly has just taken a giant leap that is likely to disrupt the space time continuum. Let us retrace our steps if you do not mind.

The onset of the First World War in 1914 was a turning point in Paquet’s career. In 1915, Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries obtained at least one major contract to manufacture shells which, once loaded with explosives by one or more other firms, would be fired by 83.8 millimetre (3.3 inch) field guns and 152.4 millimetre (6 inch) heavy field howitzers.

Said contract(s) were in all likelihood among those awarded on behalf of the British Army by the Shell Committee of the Department of Militia and Defence of Canada – a committee whose political patronage, which was not particularly… conservative, sometimes / often resulted in excessive profits. A committee replaced by the Imperial Munitions Board, a Canadian-based British body created in 1915 by Canadian businessmen to oversee the production of war material in Canada, but I digress.

Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries obviously had to obtain the necessary tools to fulfill its contract. It also had repair its facilities, which were seriously damaged by a fire in early May 1916. Would you believe that rumour had it that this was a criminal fire? The press, however, did not seem to mention the possibility that the fire was the work of German agents, although present / active in North America at the time, but back to our story.

Once its workshops were repaired and reopened, in 1917, thanks to a considerable loan from the Banque nationale of Québec, Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries became the largest employer in the Montmagny region and one of the most important and modern factories in Québec. Its staff, which numbered up to 1 100 or 1 200 people, was also recognised for its quality. Before I forget, the aforementioned Normand was the firm’s technical advisor.

This being said (typed?), Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries was apparently failing to meet its deadlines. The relationship between the firm and its creditor also deteriorated somewhat over time, especially as Paquet granted himself, according to the Banque nationale, unreasonable wages and bonuses.

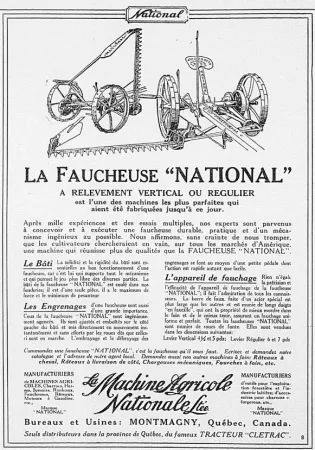

Once the First World War ended, production of shells obviously ended. Usines Générales de Chars et de Machineries returned to the production of agricultural and road machinery. It changed its name to the aforementioned La Machine Agricole Nationale in October 1919 – a moniker which, at least it was hoped, would strike the patriotic cord of French-speaking Québec farmers. To better strike said cord, the management could count on a talented copywriter, the young journalist Jean-Charles Harvey, apparently hired in 1918. Before I forget, Paquet was president and general manager of the firm.

His interest in economics led Harvey to publish his first work in the summer of 1920, the pamphlet La Chasse aux millions: L’avenir industriel du Canada-français. Convinced that they would not be able to make a living in the countryside, many young people were moving to the city, he wrote. Worse yet, many of these people were leaving Québec. Greater involvement of the French-Canadian / Québec business community in the industrialisation of Québec could help reduce this exodus. Harvey wanted this effort to focus outside of the big cities of the province and specialise in areas related to agriculture and the settlement of new lands (farm machinery factories, pulp mills, etc.), but I digress.

Despite its innovative spirit, La Machine Agricole Nationale was faced with formidable competitors and the economic crisis of 1921-22. It issued bonds and obtained significant credit from the Banque nationale. These measures proved insufficient, however. The management put the key in the door, temporarily it was said, at the beginning of February 1922 and thus laid off all the 200 employees who still worked in the shops. A rumour of a purchase by the American giant International Harvester Company turned out to be unfounded.

About 100 employees returned to work in April, under the direction of Philippe Béchard, the general manager of Compagnie A. Bélanger Limitée of Montmorency, Québec – a foundry and manufacturing firm well known in Québec and outside Québec for its magnificent wood stoves, decorated with nickel-plated pieces and / or ceramic tiles.

A little before or after the first weeks of 1922, the Banque nationale indicated it wished to obtain repayment of the sums lent over the years. Unable to find the cash which would have allowed it to stay afloat, La Machine Agricole Nationale was declared bankrupt in November.

This being said (typed?), the firm’s trustees, The Sun Trust Limited of Montréal, sold farm machinery for some time after that date. Some suggest that such (discount?) sales continued until 1924.

Although ephemeral, La Machine Agricole Nationale occupied a very honourable place in the history of the Québec / Canadian agricultural machinery industry. Its production was one of the most varied in Québec (harrows, hay loaders, plows, potato harvesters, potato planters, rakes, weeders and wagons on the one hand; churns, cream separators, pumps and wood stoves on the other hand) and it left the shops in large quantities to reach a clientele which went beyond the borders of Québec.

It should be noted that the Banque nationale did not come out of this adventure unscathed. Nay. This financial institution had to face such problems that it found itself forced to merge with the Banque d’Hochelaga of Montréal at the beginning of 1924, a merger supported financially by the government of Québec, thus giving birth at the Banque canadienne nationale of Montréal.

And no, Montmagny did not come out of this adventure unscathed either. This small town lost a good percentage of its population between 1922 and 1924.

The collapse of La Machine Agricole Nationale inspired the aforementioned Harvey to publish his first novel, Marcel Faure, in 1922. His hero was a young industrialist, the Marcel Faure of the title, for whom American materialism, widely denounced by the secular and religious elites of Québec, was not demonic.

Harvey’s fame / notoriety, however, owed more to the novel Les demi-civililisés, published in early 1934, which strongly denounces the exaggerated conservatism of said secular and religious elites of Québec as well as the stranglehold of the roman catholic church on the French-speaking population of the province. This red hot book was quickly banned from reading by cardinal Jean Marie Rodrigue Villeneuve, in residence in Québec – the city of course.

The reaction of the elites reached such a level that Harvey had to request that Les demi-civililisés be taken out of circulation. Worse still, he lost his job as editor in chief of the daily Le Soleil in Québec. Very few people spoke or wrote in defence of Harvey, but many people rushed to bookshops, especially in Montréal, to buy his book.

If truth be told, as important as it was / is in the history of Québec literature, Les demi-civililisés was not / is not really a good novel. Somewhat misogynist, it also sinned through its dialogues, plot, story and style.

The sadly short-lived (less than 9 years) weekly Harvey founded in 1937, Le Jour, gave him the opportunity to denounce said exaggerated conservatism and stranglehold, as well as the backward / archaic education system in Québec. Before the Second World War, Harvey denounced Fascist Italy and National Socialist Germany, as well as its allies, including the rebels who were then trying to crush by force the legally elected government of Spain – bloodthirsty rebels largely supported by a good part of the secular and religious elites of Québec.

During the Second World War, Harvey supported the leader of Free France, Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle – a gentleman mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since March 2018. At least for a time, a good part of the secular and religious elites of Québec, on the other hand, preferred to give its support to the puppet / collaborationist government of France and its head until April 1942, Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain, almost senile, who celebrated his 86th anniversary in the days that followed his fall from power, but I digress. Again.

Although strongly affected by the collapse of La Machine Agricole Nationale, Paquet decided to remain in Montmagny, where he had lived with his family since 1915 or 1916. In 1931, he helped set up a textile firm incorporated in October 1931, M.E. Bintz Company Limited, in the municipality. In fact, this subsidiary of an American firm, it was said, may have occupied some of the buildings used in the past by La Machine Agricole Nationale.

Paquet died in October 1936. He was then 68 years old.

The aforementioned Normand, on the other hand, left this world in December 1952, at the age of 81.

One of the main employers in Québec for decades, the textile industry gradually succumbed to the blows of textile companies in Asian countries, a region of the world where wages were much lower than those offered by firms settled in Québec. And no, the wages received by Québec workers were not particularly impressive. My father would have a lot to say about that.

In any event, a textile firm still occupied part of the facilities of La Machine Agricole Nationale at the start of the 21st century. The factory of Consoltex Incorporée, a subsidiary of the Montréal firm Consoltex Holdings Incorporated, itself a subsidiary of American Industrial Partners Incorporated it seemed, closed its doors in July 2006, however. The firm then only employed around 30 or so people whose average age was over 50. A difficult quest for employment began.

Take care of yourself, my reading friend.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)