Movie titles can be so… positive and cheerful: The Day the Sky Exploded

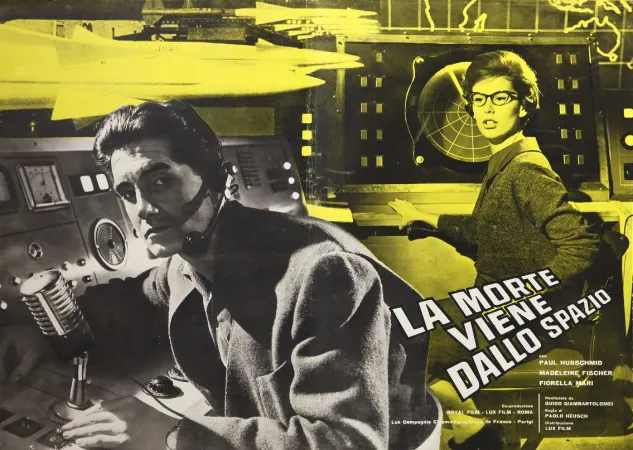

Good day / buongiorno / bonjour, my reading friend. Are you interested or, better yet, fascinated by science fiction? If so, yours truly advises you to leave this webpage. No, no, don’t go! Yours truly was joking. This being said (typed?), I must warn you that the film we are about to examine this week is not among the masterpieces of the 7th art. La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace is not without merit however. The original version of this Italian-French feature film hit theatres in Italy in September 1958.

The plot of this limited budget black and white production was as follows. Numerous newspapers around the world announced on their front page that the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) were working together, as part of a United Nations Organization project, to launch a nuclear powered rocket toward the Moon. In fact, the team that designed this technological marvel was headed by a Soviet engineer. The rocket was to lift off from the base at Cape Schark / Shark, Australia, a fictitious site, with a Soviet, British or American pilot. This pilot, the first human being launched into space, would fly over the Moon without landing.

On the day of the launch, the American John McLaren boarded the capsule of the huge rocket. A television camera mounted in front of him transmitted his image to the control centre. The rocket having lifted off without problem, McLaren went into orbit. The few meteors / meteoroids he observed seemed to pose no danger. Well attached to his seat, McLaren said he was not affected by the near absence of gravity. His morale was good but he seems a little groggy. The American briefly amused himself with a pencil floating in front of his face.

Delighted by this turn of events, the control centre staff toasted to the health of McLaren. Their joy gave way to anxiety when radio contact with the rocket was cut while it was flying over the Moon. McLaren found himself in an emergency situation. The rocket moved away from the intended course and he failed to remedy the situation. In desperation, McLaren operated the device that separated his capsule from the rocket. He returned to Earth safe and sound, much to the relief of everyone.

The rocket, meanwhile, continued its crazy course. It exploded in a region of the solar system where there were asteroids. The explosion caused the agglomeration of many of them. Without anyone on Earth knowing, the massive swarm born of this fusion soon began to move towards our planet. It was quickly detected, however.

Strange radio signals were soon picked up on Earth. Equally strange light effects appeared in the heavens. The canine companion of the staff of the control centre, Geiger, was affected very quickly. The Earth’s magnetic field decreased and the temperature began to rise. Many parts of the world were affected by floods or fires. As the situation deteriorated, many birds and mammals began unforeseen migrations.

Some researchers, however, pointed to a glimmer of hope. The asteroid swarm would move so close to the Moon that its trajectory could be affected. Many asteroids could also hit our satellite. This being said (typed?), assuming that the Earth did not suffer a direct impact, its coastal regions would be devastated by terrible tsunamis. It was therefore necessary to evacuate threatened populations inland. There was panic and there were riots. As the hours passed, the world held its breath. The hoped-for miracle did not occur. The trajectory of the largest asteroid had not really changed.

A researcher by the name of Randowsky cracked under the pressure of events. He shouted that the swarm of asteroids moving towards Earth was a divine punishment. Space exploration was in fact carried out using rockets derived more or less directly from intercontinental ballistic missiles with (thermo)nuclear warheads. His remarks, however incoherent, gave McLaren an idea.

The major powers had to launch their intercontinental ballistic missiles in the direction of the asteroid swarm. The explosion of their warheads could save humanity. The calculation of the missiles’ trajectories obviously required complex calculations that could only be performed by the computers at the base of Cape Schark. Global warming was heating up the room where the computers were, however. Their operation being threatened, the cooling system had to operate at full power. Wielding a weapon, Randowsky seemingly shut down that system. McLaren and a group of researchers rushed him. A researcher died, victim of a bullet. Randowsky died from electrocution.

Once the cooling system was restarted, the computers performed their calculations. McLaren gravely emphasized that the survival of humanity now depended on the weapons created to destroy it. A swarm of missiles, up to 3 000 perhaps, rose shortly thereafter. Explosions destroyed and / or diverted the asteroids. The Earth was saved. Geiger was very happy. The end.

Let me start my analysis of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace by pointing out that it was one of the first, if not the first Italian science fiction film. And no, my reading friend, this was not the first film whose plot was based on a celestial body that threatened our dear old Earth. Just think of disaster films like La fin du monde by Abel Gance, born Abel Eugène Alexandre Perthon, and When Worlds Collide by Rudolph Maté, born Rudolph Mayer, released in 1931 and 1951 in France and the United States. These 2 feature films were not the first films of this type either.

Aware that the world in which it lived was subject to strong tensions caused by the Cold War, the production team of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace wanted to convey an optimistic message to viewers. It suggested that the United States and the USSR could put their rivalry aside in order to cooperate on space exploration. Better yet, these 2 superpowers could work together to save humanity. If the optimism of the production team seemed naive, there was no denying the need to reduce the tensions caused by the Cold War. The survival of the Earth as an environment capable of supporting life depended on this.

As was said (typed?) above, the Italian version of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace arrived in theatres in September 1958. The French version followed in February or July 1959. Given the fact that the cast of characters included comedians born in various countries of the world (Brazil, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland for example), yours truly would really like to know which language(s) all of these beautiful people spoke during the shooting. In fact, the dialogues of certain characters were doubled in the French version of the film.

In a completely different vein, let me mention that the American and British premieres of our feature film were held in September 1961 and on an undetermined date (1960?). Yours truly must admit that he does not understand why the title of the film presented in the United States, The Day the Sky Exploded, differed from that offered to British moviegoers, Death Comes from Outer Space. This being said (typed?), I would like to submit a suggestion to film clubs and cinemas. They should consider the possibility of offering a dual program including The Day the Sky Exploded and an American feature film released in June 1957, The Night the World Exploded. Just sayin’. Before I forget, please note that this latest disaster film described the adventures of researchers dealing with a series of violent earthquakes.

Interestingly, the voice of the person reading the lines of dialogue of a female laboratory assistant was very similar to that of Lois Maxwell Marriott, born Lois Ruth Hooker. A few years later, this largely unknown Canadian actress lent her face to a character both secondary and iconic of one the most important series of feature films of the 20th and 21st centuries, Eve / Jane Moneypenny, executive assistant of the boss of the British secret agent James Bond, a well-known character mentioned in a May 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The voice of the person reading McLaren’s many lines of dialogue, on the other hand, was very similar to that of Canadian actor Shane Rimmer. And here lies a tale. Sorry.

After overseeing the production of 3 highly innovative children and teenage television series taking place on Earth, in space and under the sea, the United Kingdom’s Gerry Anderson, born Gerald Alexander Abrahams, launched Thunderbirds in September 1965, with the help of his wife, Sylvia, born Sylvia Thamm. This series, by far his most popular, also used a technique called Supermarionation, based on the use of wire puppets. Thunderbirds showed the adventures of an international rescue team whose secret base was on an island on which lived its leader, a former American astronaut, Jeff Tracy, his 5 sons, as well as their colleagues and friends. A technological utopia with few visible minorities, Thunderbirds took place in the 2060s.

If I may say so, some of you may have seen Thunderbirds puppets in a video by Dire Straits, one of the most important British rock bands of the 1980s. Produced in 1991 and co-directed by Anderson, Calling Elvis also featured wire puppets that reproduced the traits of band members.

To some extent, Anderson designed Thunderbirds based on the lucrative American market. He gave Tracy’s sons the first names of 5 American astronauts from the Mercury program of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, for example. Three now largely forgotten Canadian actors, the aforementioned Rimmer, as well as Peter Dyneley and Matthew Zimmerman, lent their voices to the characters of Scott, Jeff and Alan Tracy. A fourth, Jeremy Wilkins, replaced an American who had returned home. He lent his voice to Virgil Tracy. Interestingly, Anderson and his team gave their many puppets the appearance of more or less well known actors. One only needs to think of Thomas Sean Connery, Charlton Heston, born John Charles Carter, and Anthony Perkins. Jeff Tracy was portrayed by a well-known Canadian actor and Canadian Broadcasting Corporation announcer during the Second World War, Lorne Greene, born Lorne Himan Green. Anderson believed in all likelihood that the voices of British comedians would be less appealing to young American viewers.

And yes, my reading friend, the astronaut of the Mercury program whose first name was Virgil was none other than Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom, mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Give yourself a little gold star and buy yourself a corned beef sandwich, because you’re worth it.

The 64 episodes of Thunderbirds aired between September 1965 and December 1966. Over the years, this series was translated and broadcasted in at least 65 countries, including Canada – and Québec. It gave birth to a multitude of products, from milk chocolate bars to figurines, as well as comic books, novels and video games.

In the latter case, let me mention Thunderbirds, launched in 1985 by Firebird Software Limited, a subsidiary of the Telecomsoft Division of a British giant, British Telecommunications Public Limited Company. At least one other British company, Activision Incorporated, publishes a game called Thunderbirds, in 1990. At least one of these products was available in a version compatible with one of the most famous British computers of all time and one of the most important personal computers in the history of video games, the Sinclair Research ZX Spectrum, or “Speccy,” launched in 1982.

Anderson and his crew produce 2 feature films, Thunderbirds Are Go and Thunderbird 6 that did not prove very successful. A third movie, Thunderbirds, released in 2004, used live actors. It was not very successful either. A Japanese animated series, Thunderbird 2086, went on the air in 1982. Another animated version, Thunderbirds, arrived on television in 2015. It was not particularly interesting, and I am really moving away from our topic. Profuse apologies.

Now let’s go over some aspects of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace. Before going any further, yours truly must emphasize that Australia played a role in the evolution of a well-known graphic novel character. Dan Cooper, a Canadian fighter pilot imagined by Belgian cartoonist and scriptwriter Albert Weinberg, traveled to that country to test the Triangle Bleu, a supersonic vertical take-off fighter designed by his father. The Belgian illustrated weekly Tintin presented this first Cooper adventure to its readers from December 1954. Weinberg’s stories dealt with space more than once. They were also close to science fiction, especially in the 1950s. A symbol of Canadian duality, Cooper has an anglophone father and a francophone mother. Over the years, he served with the British Royal Air Force, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and the Canadian Forces.

Would you believe that a nuclear powered rocket was used to send a graphic novel hero known around the globe all the way to the Moon? This episode of the adventures of Tintin was originally published, in French, in the illustrated weekly Tintin between May 1952 and December 1953. And yes, this epic journey was mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to our story.

The scenarios of 3 adventures that the Belgian Jean-Michel Charlier wrote to help Weinberg, then overworked, represented a turning point. The latter found there lessons that were valuable to him. Charlier acted in secret in order not to get in trouble with the direction of the Belgian illustrated weekly Spirou, for which he wrote the scenarios of the adventures of Buck Danny, another classic aeronautical graphic novel series. No less than 20 million copies of the 54 albums detailing the adventures of this American fighter pilot were published between 1948 and 2015. The first story appeared in fact in Spirou as early as 1947. And yes, my reading friend with good eyes wide open, this weekly was mentioned in a June 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

By way of comparison, no less than 25 million copies of the 41 albums detailing Cooper’s adventures were published between 1957 and 1992. Over the years, Cooper’s adventures were translated into several languages, but not in English, which was a bit curious considering the popularity of the character among the officers of the RCAF and the CAF. Yours truly remembers receiving as a gift an album detailing one of Cooper’s adventures in the late 1960s.

It should be noted that the main daily of Québec, Québec, Le Soleil, published an episode of the album 3 cosmonautes each week, between February 1971 and April 1972. Canada’s main French-language daily newspaper, La Presse of Montréal, Québec, did the same with the album Les hommes aux ailes d’or, between August 1975 and June 1976.

In November 1971, a man who called himself Dan Cooper, and not D.B. Cooper, hijacked a jet airliner over Oregon. He later parachuted out and vanished. Around 2007, the Federal Bureau of Investigation agent who inherited the file concluded that this famous hijacker, probably a former member of the United States Air Force who had served in Europe, chose his alias to “honour” the character created by Weinberg. A poor quality American film released in 1981, The pursuit of D.B. Cooper, went over this truly fascinating tale.

The National Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, offered a fascinating exhibition on Cooper to its visitors in 1994. Great job, MD! Some other Canadian institutions borrow Dan Cooper: Canadian Hero in the following months, but let’s move back to today’s topic.

By the way, a third French-language aeronautical graphic novel series was created in 1959 in the new French illustrated weekly Pilote. The aforementioned Charlier teamed up with Albert Uderzo, born Alberto Aleandro Uderzo, to create Michel Tanguy and his friend Ernest Laverdure. The adventures of these 2 fighter pilots in the French air force, the Armée de l’Air, were found in 29 albums published in 6 million copies between 1961 and 2015. As early as 1960, Radio Luxembourg or, more precisely, the Compagnie luxembourgeoise de télédiffusion, broadcasted a weekly radio drama devoted to Tanguy and Laverdure and other characters of Pilote, including Astérix the Gaul, one of the great French graphic novel characters of the 20th century.

The great popularity of Tanguy and Laverdure led to the creation of 2 television series, Les Chevaliers du ciel and Les Nouveaux chevaliers du ciel, on the air in 1967-69 and 1988-91. The theme song of the first series was performed by none other than France’s Elvis Aaron Presley, Johnny Halliday, born Jean-Philippe Smet. A not overly successful movie, Les Chevaliers du ciel, had its premiere in 2005. Yours truly remembers seeing episodes of Les Chevaliers du ciel on television in the 1970s, in Québec.

This being said (typed?), Uderzo no longer drew the adventures of Tanguy and Laverdure from 1966 onward. Other characters, more popular still, occupied most of his time. Indeed, Uderzo and René Gosciny launched the adventures of the aforementioned Astérix and his friend Obélix. No less than 8 cartoonists replaced Uderzo over the years. The death of Charlier, in 1989, meant that no album of the adventures of Tanguy and Laverdure got published between 1988 and 2002.

Where was I? Oh yes, I was reviewing some aspects of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace. Several commentators noted the presence of numerous extracts of archival or newsreel footage throughout this film. This disparate material was, all in all, well assembled and used. One only needs to mention the sad scenes of people fleeing coastal regions. Similarly, the look and feel and special effects of the film were not bad. Just think of the model of the lunar rocket, very elegant and well filmed at takeoff and later in space. Let’s not forget either the original music of the film, which added a lot to the feeling of danger coming from space all and this even though it was a tad annoying at times. La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace was actually part of a new phase in the evolution of Italian cinema. The studios were trying to break into the lucrative British and American markets with films that resembled those produced in these countries.

Let me underline the absence of Italian or French pilot candidate for the lunar rocket of La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace. Such an absence was surprising in an Italian-French film. In fact, the cast did not include many French actors. Even worse, one of the few characters identified as French was an arrogant masher. Would you believe that this unsavoury researcher dared to bet with colleagues that he could seduce the pretty but cold mathematician of the team? She slapped him when she realized what was happening. Ironically, it was these 2 characters who oversaw the calculation of the missiles’ trajectories and saved the world.

Taken as a whole, the actions and / or comments of the characters in the film as a whole bordered on caricature. The very length of the scenes filmed in the control centre made this deficiency more visible.

The decision of the film crew to place McLaren, an American, in the lunar rocket capsule, may have been due to the fact that the United States was at the forefront of economic and military power. Americans also bought a lot of movie tickets. Be that as it may, McLaren was a man of action. He wore a suit and helmet when he stepped aboard the lunar rocket’s capsule. This being said (typed?), the visor of said helmet did not completely cover his face – a potentially fatal deficiency in case of damage to the capsule. The presence of a television camera inside of it was, however, prophetic to say the least. Such a camera was indeed inside at least 1 Vostok space capsule as well as in 1 Mercury space capsule, launched respectively by the USSR and the United States in the 1960s. The staff of the Soviet and American ground control centres could not converse with cosmonauts / astronauts, however. And yes, my reading friend, the Vostok space capsule was mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

If McLaren, well attached to his seat, did not float during his journey in space, the scene showing the pencil with which he played illustrated well and at a low cost the weightlessness that prevailed aboard the capsule. The presence of meteors / meteoroids was not unusual in feature films of the time. In short, McLaren’s flight was presented in a realistic way.

Things started to go wrong from a realism point of view when the explosion of the rocket caused the creation of a swarm of asteroids – a paradoxical result. The phenomena that affected the Earth, from the drop of the magnetic field to the fires, were just as absurd.

As original and well-intentioned as it was, the use of intercontinental missiles to destroy the asteroid swarm was hardly realistic. Weapons available or under development at that time, the Soviet Korolev R-7 and the American Convair SM-65 Atlas, for example, 2 missiles mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, could not rise to a very great distance from the Earth. Their explosion, even simultaneous and at a precise point, could neither destroy nor deflect a huge asteroid. Assuming that the latter broke apart, the damage would still have been catastrophic.

Unlike some American or British space films of the time that included disasters, La morte viene dallo spazio / Le danger vient de l’espace suggested that the exploration of space should not continue. Maybe there was a limit that we were not allowed to cross, said one of the researchers in the control centre. Please do not hesitate to ponder this question, my reading friend. I will be here next week, if the sky does not fall on my head, by Bélénos, by Toutatis and by any chance.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)