Once upon a time there was an acrobat tractor: The beautiful although partly military story of the Pavesi P4 farm tractor and the career of Ugo Pavesi

Hello, my reading friend, hello.

It is with a certain trepidation that yours truly approaches the subject of this week. I feel a certain discomfort at the idea of talking about an agricultural tractor designed in Italy during the years during which the Partito nazionale fascista, an unsavoury organisation led by Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini, a pompous brute and buffoonish dictator mentioned since August 2018 in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, held the reins of power.

This being said (typed?), I dare to hope that it is possible to examine the story of the Pavesi P4 despite the monstrousness of the political regime which oversaw its birth. I dare to hope that you share that point of view.

So let us start at the beginning. Ugo Pavesi was born in July 1886, in Italy. The childhood and adolescence of that brilliant young man took place in a culturally elevated and financially secure environment. Driven by an overwhelming passion for mechanics, he enrolled in engineering with a specialisation in mechanics at the Regio Politecnico di Torino. Pavesi graduated in 1909.

Pavesi’s first job, at Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino Società Anomima (FIAT) it seemed, a firm mentioned several times since March 2019 in our blog / bulletin / thingee, was interesting but it did not take long for him to leave it. With a free spirit and a few projects he would have liked to realise, Pavesi came to the conclusion that he needed to start his own firm.

Pavesi contacted various financial institutions which politely refused to lend the necessary funds to that illustrious 23 or so year old nobody. Pavesi realised he needed an older partner whose seriousness, professionalism and financial resources would overcome the bankers’ hesitation. He found that rare gem in the person of engineer Giulio Tolotti, who became his friend. A bank agreed to help the dynamic duo. La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti Società Anónima was created in 1910. Pavesi reserved for himself the positions of general manager and designer.

La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti presented a 3-wheel motorised plow at the Esposizione internazionale dell’industria e del lavoro di Torino, held in Turin, Italy, between April and November 1911. Would you believe that this vehicle, which some considered / consider to be the first Italian agricultural tractor, won a silver medal?

Towards the end of 1913, La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti launched a new tractor, the America. Once modified, that vehicle became a heavy artillery tractor used by the Italian army, the Regio Esercito, during the First World War. Indeed, that terrible conflict constituted a turning point for the young firm.

An ally of the German Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire since 1882, Italy declared itself neutral when the First World War broke out – to the great displeasure of its allies. Italy was favourable, however, to the idea of joining one or the other of the alliances involved in the conflict, provided that its political and territorial demands were met. As the Austro-Hungarian Empire did not wish to see some of its border territories absorbed by its “ally,” Italy joined the conflict alongside the United Kingdom, France and the Russian Empire in May 1915, the British and French governments willingly agreeing to hand over to their new “ally” territories which did not belong to them, once the war was over of course.

It went / goes without saying that the terms of these negotiations, which were all in all quite unsavoury, negotiations detailed in the Treaty of London, had to remain secret, just like the treaty actually.

Dare I paraphrase my father, in translation, at this point? What do you think of the following comment? If you put a skunk in a big bag with some politicians, that poor creature would come out first because the stench was just too unbearable. Too controversial, you say? Very good. I will therefore not paraphrase my father in this text.

A brief, well, a fairly brief digression if I may. At the risk of oversimplifying things, the Russian Empire gave way to the Rossiyskaya Sovetskaya Respublika in 1917, as a result of the October Revolution. The new government established through brute force by the Rossiyskaya Kommunisticheskaya Partiya (bol’shevikov) (RKPb) then found various secret treaties signed since the start of the First World War, including the Treaty of London. Hoping perhaps to ignite anti-war sentiment and propagate the communist revolution within allied countries (United States, United Kingdom, Italy, France, Canada, etc.), the RKPb published these treatises in its dailies, Izvestia and Pravda, and this from November 1917 onward.

As you may imagine, such news reached the ears of American, British, Canadian, etc. dailies, which published it. In public, the British and French governments claimed that the treaties in question were forgeries. In private, they were furious to see their all in all quite unsavoury negotiations exposed to the light of day.

The actions of the RKPb helped to concrete, sorry, cement the impression of the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, etc. that said party was in the pay of the German Empire. The peace treaty signed by the Bolshevik and German governments in March 1918 did not improve matters. Allied troops, including Canadian troops, thus participated in the terrible Russian civil war between 1918 and 1920, on the side of the anti-Bolshevik forces obviously. This being said (typed?), the RKPb ended up winning that war. Its leaders would not soon forget the overt hostility of Western countries, but back to our story.

La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti filled many orders for the Regio Esercito during the First World War. Pavesi demonstrated great professionalism and avoided any compromise or favouritism – an uprightness noted in a letter of recommendation signed by the Regio Esercito’s chief of staff, Major General Armando Diaz, after the conflict was over.

Given the predictable victory of Italy and its allies, Pavesi designed an almost revolutionary agricultural tractor in 1918. Indeed, he was familiar with the difficulties faced by Italian farmers in plowing their fields in wet weather. Neither oxen nor the still rare agricultural tractors were effective in muddy terrain.

The very concept of the P4 tractor, that is 2 large metallic driving and steering front wheels and 2 large metallic driving and steering rear wheels, all of the same size, with an articulation system between these 2 sections, made it a particularly agile vehicle. The P4 was in fact the first Italian 4-wheel drive tractor – and one of the first in the world. It was also the first Italian articulated tractor – and one of the first in the world.

Tests carried out near Rome in the summer of 1918 caused a sensation. The P4 indeed operated excellently in rough terrain and offered good grip even on muddy ground.

The obvious qualities of P4 aroused the interest of an Italian industrial giant, Giovanni Ansaldo & Compagni Società in accomandita semplice, whose subsidiary, Società Agricola Italiana, was then very active. A plan to acquire La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti went nowhere, however.

In fact, Italy was going through very difficult times at the time. That period of political instability and high unemployment between 1919 and 1921, known as the Biennio Rosso, or two red years, gave rise to more or less violent workers’ protests and mass strikes. It also opened the door to the October 1922 coup d’état which put into power Mussolini and the Partito nazionale fascista.

At the end of his tether, Tolotti sold his shares around 1921. Now alone, Pavesi reorganised La Moto Aratrice Brevetti Ingegneri Pavesi & Tolotti which then became La Motomeccanica Brevetti Ingegnere Pavesi Società Anónima.

The P4 distinguished itself in various demonstrations and competitions which took place in Italy during the 1920s. Members of the royal family, the house of Savoia, even Mussolini himself, often attended these events. The dictator apparently got behind the wheel of a P4 on at least one occasion, to satisfy photographers and cameramen – and his personal vanity. While Pavesi was one of the multitude of acquaintances of the “Duce,” his relations with him and the Partito nazionale fascista seemed purely formal. He was apparently neither a supporter nor a detractor of the Mussolini regime.

While it was true that the agility of the P4 surpassed that of any other tractor used in Italy, the fact was that it was an expensive to buy and complex to maintain vehicle. In 1929, for example, a P4 cost about 45 000 lire, compared to around 27 000 lire for a more conventional tractor. The P4 was therefore not very popular with small and medium-sized operators.

This being said (typed?), the sheer excellence of the P4 ensured that it remained in production until 1942. Better yet, it was produced under license in 2 or more European countries, in both civilian and military versions. It went / goes without saying that P4s were exported to several / many countries in Europe and, possibly / probably, some colonial territories in Africa.

And yes, you guessed it, the success the P4 lacked in agriculture came from the military. A modified version of that vehicle won a competition organised in 1923 by the Ministero della Guerra to find a heavy artillery tractor. While La Motomeccanica Brevetti Ingegnere Pavesi manufactured a small number of Trattore pesante campale Modello 25, it did not have the resources to manufacture the 1 000 new improved heavy artillery tractors, designated Modello 26s, that the Regio Esercito wished to obtain in the time limits requested, that is 4 years.

FIAT thus acquired the production license for the Modello 26. A subsidiary of that important Italian automobile manufacturer, Società Piemontese Automobili, manufactured some, if not perhaps all of these vehicles from 1928 onward. The same went for many improved Modello 30s, manufactured until around 1938. These heavy artillery tractors played a fundamental role in the motorisation of the Regio Esercito during the 1920s and 1930s.

It should be noted that FIAT committed not to sell civilian versions of the Modello 26 or 30.

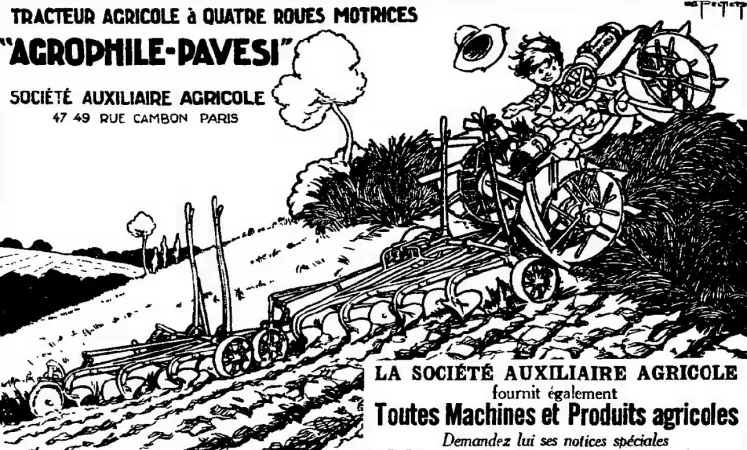

Would you like to know the names of some foreign firms which manufactured P4s under license? And yes, that was a rhetorical question. You are going to get it whether you like it or not. Armstrong Siddeley Motors Limited, a subsidiary of British industrial giant Vickers-Armstrongs Limited, and Weiss Manfréd Acél és Fémművek, Hungary’s largest metallurgical plant, were among these foreign firms. Yours truly does not know if that list included any other names. And yes, the Société auxiliaire agricole was perhaps on that list. That French firm, whose advertisement illustrated our subject today, marketed the P4 under the name Agrophile-Pavesi.

Before I forget, the armed forces of several European countries, including Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Hungary and Sweden, used one version or another of the Pavesi heavy artillery tractor, for many years.

In 1928 at the latest, La Motomeccanica Brevetti Ingegnere Pavesi undertook the design of an agricultural tractor which was to succeed the P4. The Pavesi Balilla hit the market around 1929-30. The firm also launched a tracked tractor, also called Pavesi Balilla, in 1933. These vehicles remained in production until around 1951-52.

The term Balilla was well known in Italy by the time the 1920s came to an end.

During the so-called War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), troops of the Austrian-led alliance invaded the Repúbrica de Zêna, allied to the opposing alliance, and occupied the city of Genoa itself. The Genoese suffered a lot during that occupation. In December 1746, the population rose up. Legend had / has it that the trigger for the insurgency was a stone thrown by an 11-year-old boy, Giovanni Battista Perasso it was / is said, known as Balilla it was / is said. The hated invader was driven out within days. The young boy became to all intents and purposes a national hero following the creation of Italy as a country in March 1861.

The Partito nazionale fascista took advantage of the character’s fame when it created a youth organisation, the Opera nazionale Balilla per l’assistenza e per l’educazione fisica e morale della gioventù (ONB), in April 1926, to instill suitable cultural, military, physical, professional, spiritual, sports, technical, etc. education / training to young Italians, both boys and girls, aged 6 to 18. If registration was not compulsory before 1937, date of the disappearance of the ONB in favour of a new youth organisation, the Gioventù italiana del littorio, non-participation was not particularly well received by the Partito nazionale fascista, but back to our story.

In 1933, the economic and banking crises which rocked Italy, and much of the world, brought La Motomeccanica Brevetti Ingegnere Pavesi into the arms of the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI), the main entrepreneur and banker of Fascist Italy. That state body strengthened production and organised sales. La Motomeccanica Brevetti Ingegnere Pavesi thus became the third largest Italian tractor manufacturer.

Pavesi died suddenly, in July 1935, just 4 days short of his 49th birthday, but his firm survived him. Indeed, it also survived the Second World War.

The high number of models of tractors produced once peace returned turned out to be a heavy and cumbersome burden for the IRI, however. It therefore refused to invest more money in the firm, whose name might have changed over the years. As a result, production of tractors came to an end during the first half of the 1960s. The noble Motomeccanica brand then disappeared forever.

And it is my turn to disappear… until next week. Ciao.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)