Tomanowos, a visitor from the sky or Moon: A brief look at the largest North American meteorite known today

Hello there, my reading friend. Given the name of the breathtaking and world-famous Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, it occurred to yours truly that a space rock would make a nice anchor for an issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

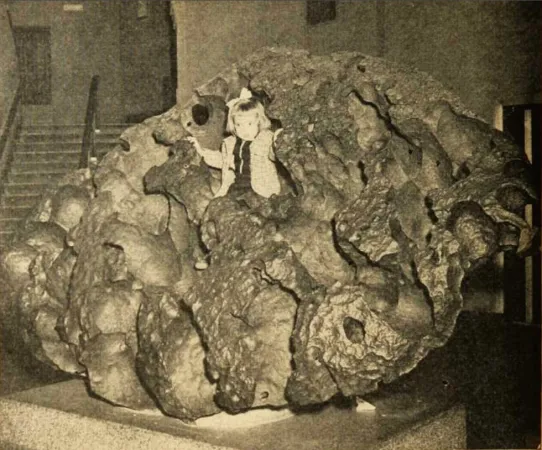

Let us therefore begin this pontification by quoting, in translation, the caption of the photograph found in a February 1947 issue of the illustrated weekly Le Samedi, published in Montréal, Québec.

A fireball which fell near the city of Oregon, United States, in 1902 has recently been on display for New Yorkers to see. This very interesting specimen weighs [14 000 kilogrammes] fifteen and a half tons and, to get a fair idea of its dimensions, you will notice the little girl who has taken her place in one of the cavities in the centre of this enormous mass of metal coming from space.

If I may be permitted to nitpick for a moment, a rare occurrence you will admit, the Willamette meteorite did not fall near Oregon City, Oregon, in 1902 and it had been on display in New York City, New York, for quite some time.

The truth is, and no, we will not look into the existence or non existence of truth as an absolute today. The truth is that no one knows when, or where, the Willamette meteorite and our planet had a close encounter of the colliding kind. To paraphrase an old Québec expression, in translation of course, the good lord knew and the devil suspected, to which my father would add that he had no clue whatsoever (Le bon Dieu le sait et le diable s’en doute, mais mon père ne le sait pas pantoute).

The Librairie Pantoute, by the way, is a magnificent independent bookstore whose two branches are located in Québec, Québec, but I digress.

It looks as if the meteorite crashed on the ice sheet which covered what is now British Columbia and parts of what are now Idaho, Montana and Washington. A glacier slowly dragged it close to a 600-metre (2 000 feet) high ice barrier which had formed across a river, thus forming a huge body of water, Lake Missoula. Around 13 000 years ago, the increasingly unstable barrier gave in under the pressure.

The resulting cataclysm was, well, beyond anything our puny minds could imagine. Yea. Can you indeed imagine up to 3 000 Niagara Falls coming straight at you? The sight, the sound, the terror? To paraphrase the idiotic president of the United States in the popular 2009 animated science fiction comedy motion picture Monsters vs. Aliens, should someone put you on code brown because you need to change your pants?

One of the ginormous ice rafts which destroyed everything in their path carried the Willamette meteorite more than 650 kilometres (400 miles) to the west. The visitor from the sky finally settled near Oregon City and West Linn, Oregon, in the valley where the Willamette River flows today.

The Indigenous people who inhabited the area eventually came across this huge mass of metal (91 % iron and 7.6 % nickel). Understandably enough, they were deeply impressed and puzzled. The Clackamas, for example, came to venerate the meteorite, sent to them by the Sky People / Sky Beings / Above People, which they called Tomanowos, or visitor from the sky / visitor from the Moon / heavenly visitor.

The Clackamas believed that Tomanowos possessed supernatural powers. Young men visited the meteorite and spent a night near it to commune with the spirits. Men about to go into battle dipped the tip of their arrows in one of the meteorite’s many waterfilled cavities.

The name Tomanowos itself was / is puzzling. How could the Clackamas have known, hundreds if not thousands of years ago, that the Willamette meteorite was indeed a visitor from the sky? You see, right until the late 1700s, if not the early 1800s, virtually all members of Europe’s scientific elite consistently mocked the illiterate peasants who claimed they had seen rocks falling from the sky.

I mean, peasants of 1800, what did they know? What could one possibly learn from observation? Had they consulted the 2 100-year-old treatises of the great Greek philosopher and polymath Aristotélēs, a smart guy who did not waste his time observing, they would have learned that rocks cannot fall from the sky. Period. Observation? Humbug. One might as well state that women deserve to have the same rights as men, or that vaccines are not part of a plot to enslave humanity, but I digress.

And no, even if the Clackamas had concluded that the Willamette meteorite had fallen from the sky before they first made contact with white settlers / invaders, they did not do so because they had been visited by beings from another world, but back to our story.

In 1902, a resident of Portland, Oregon, Ellis G. Hughes, came across the Willamette meteorite. He too was presumably deeply impressed and puzzled. Oddly enough, newspapers articles published at the time inferred that Hughes might have been the first white settler / invader, if not the first person, to have become aware of the meteorite’s existence. Better yet, the articles inferred that the latter had fallen to Earth quite recently.

Such a conclusion brings to mind the American Hiram Bingham III, the history lecturer at Yale University who discovered the ruins of the Tahuantinsuyu / Inca city of Machu Picchu in July 1911. That discovery came as a great surprise to the local people. Someone had obviously forgotten to tell them the city had been… lost. Some white, male naked apes can be a pain in the neck, can they not? But who listens to a local population anyway? Its voice does not count for much, but I digress. Again.

A brief digression if I may. Between 1911 and 1915, Bingham led 3 archaeological expeditions to Machu Picchu with the support of Yale University and the National Geographic Society – and a permission from the Peruvian government. He shipped more than 4 000 objects to the United States, including bones, jewelry, mummies and pottery. Many of these objects were soon put on display at the Peabody Museum of Natural History affiliated with Yale University. And yes, I too wonder what bones, jewelry, mummies and pottery were doing in a natural history museum.

Incidentally, the American financier George Peabody was / is widely regarded as the father of modern philanthropy. He was, however, quite thrifty, if not miserly, toward his employees and relatives.

Given its understanding that said objects had been loaned and not given to the “yanquis,” the Peruvian government officially requested their return in 1918 and 1920. The Peabody Museum of Natural History returned only certain objects, the less valuable and important ones. The Peruvian government returned to the attack in 2001. If the National Geographic Society gave its approval to the requested restitution, the museum refused. Adding insult to injury, it launched a magnificent and very popular traveling exhibition in 2003, Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas.

An agreement negotiated in 2007 by the American university and the Peruvian government was not finalised.

Would you believe that, in 2008, Yale University only agreed to return approximately 385 of the objects from Machu Picchu, even though it recognised that all said objects belonged to Peru? Outraged by what someone, not me of course, could describe as a display of museal arrogance, the Peruvian government launched a legal action in December 2008. A change of venue delayed things but Yale University finally agreed to sign an agreement in November 2010, in which it committed to return the objects from Machu Picchu.

Dare I say (type?) that… Too offensive, you say? Alright, I will not dare. May I suggest instead that Bingham was one of the individuals who inspired a certain Dr. Henry Walton “Indiana” Jones, Junior, or that “Indy” was a tomb robber? No? You are no fun, but thanks for having my rear end. (Hello, EP!) End of digression.

For some reason or other, possibly because he thought the meteorite was very valuable, Hughes gradually moved it down, using a rude wagon, from the slight knoll where it sat, upright if you must know, to a piece of land he owned. Covering the 1 200 metres (4 000 feet) separating point A from point B took about 3 months. Hughes soon built a shed around the meteorite and charged an admission fee to see it.

The catch was that Hughes did all that behind the back of Oregon Iron and Steel Company, which owned the piece of land where the meteorite had sat. As you may understand, the management of that pipe foundry was not amused. It sued Hughes around November 1903 and demanded that the meteorite be returned to its original location. Oregon Iron and Steel won its case. Hughes was now in a tricky situation. Pushing the massive mass of metal uphill was a physical impossibility. Concerned by the potential repercussions of his defeat (Fine? Jail? Both?), Hughes decided to appeal the court’s decision.

In the meantime, in December 1904, Rudolph Koerner and P.J. Meyer, respectively a well-known and respected resident of Oregon City and a bank cashier living in that city, launched a suit of their own against Oregon Iron and Steel. The meteorite had fallen on land they owned, they claimed, but had been removed at some point by persons unknown.

The judge, jury, lawyers, etc. visited the piece of land in question in mid January 1905. They duly saw a sizeable hole in the ground. Witnesses speaking on behalf of Oregon Iron and Steel proved, however, that said hole was not natural in nature. Indeed, it had been blasted very, very recently. Koerner and Meyer lost their case. Yours truly has yet to find any information on what penalty the duplicitous duo faced, if any.

The aforementioned second trial requested by Hughes was held in 1905. Two Indigenous elders, a Klickitat and a Wasco, the Clackamas being all but extinct by then, confirmed that the meteorite had been part of tribal ceremonies and rituals. Back then (and still today?), such oral claims did not carry much weight in white men’s courts. Indeed, Oregon Iron and Steel’s lawyer actually denied that the meteorite was an Indigenous relic.

As a result, holding that there was not sufficient evidence from which a jury would be permitted to infer that the meteorite had once been an Indigenous property which had been abandoned, as claimed by Hughes, or that it was an Indigenous relic, the chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, Charles Edwin Wolverton, concluded in July 1905 that the latter could not claim to have become the new owner of the meteorite by virtue of its discovery. Hughes found himself once again in a tricky situation. Yours truly does not know what penalty (Fine? Jail? Both?) he was faced with.

A brief digression if I may. The possibility that the Willamette meteorite might be an Indigenous relic, as stated by Wolverton in his decision, did not seem to matter all that much. It was on land which belonged to Oregon Iron and Steel and that was that. The fact that Indigenous people had known about the meteorite for hundreds if not thousands of years did not matter one whit. How arrogant. How typical.

In any event, at some point in 1905, presumably after Wolverton’s decision, Sarah Tappan Dodge, born Hoadley, purchased the Willamette meteorite for the measly sum of $ 26 000 (approximately $ 820 000 in 2022 currency).

For those who care about such things, Hoadley was the spouse of William Earl Dodge Junior, a wealthy businessman and philanthropist who had made his moolah in mining.

The Willamette meteorite soon went on display at the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair, held in Portland between June and October 1905. A decision to that effect had seemingly been taken no later than January of that year, quite possibly by Oregon Iron and Steel.

After that exhibition closed, Hoadley donated her extra-terrestrial pebble to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, New York, in 1906. The Willamette meteorite may, I repeat may, have been on display there since 1935, seemingly in the Hayden Planetarium.

Charles Hayden was an American banker, businessman, financier and philanthropist. He was said to be one of those people who are too busy to hold political office, but determine who shall.

By the time the meteorite went to the museum, dozens of people, all right, all right, dozens of white men and boys, had chiseled off nickel-sized pieces, which can still be found in private homes in Oregon and elsewhere. Some white, male naked apes seem to think they can do anything they want. It is unfortunate that the police chose not to arrest any of those vandals. Dare one suggest that some policemen… Too dangerous a thought, you say? A very good point. I shall not dare.

The following decades were much kinder to the Willamette meteorite.

Around 1990, 28 000 or so Oregon schoolchildren signed a high-profile petition requesting that it be returned to Oregon. Two of them made a good impression when interviewed by the host of a very popular American television show, The Tonight Show, John William “Johnny” Carson – a gentleman mentioned in a January 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Even though the Oregon State Senate and one of the Oregon senators sitting in the United States Senate supported their cause, the initiative, channelled by the Help End Willamette Meteorite Absence Committee, was politely ignored by the American Museum of Natural History. Something about having to punch a hole through a building, which begs the question of how the museum hag gotten that huge hunk of metal inside the building in the first place. Sorry.

In November 1999, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde (CTGR), a confederation of Indigenous communities / tribes which included descendants of the Clackamas, filed an action pursuant to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act against the American Museum of Natural History, demanding that the meteorite be turned over to its members. In turn, the museum filed an action of its own in March 2000, seeking a declaratory judgment against the CTGR. A nice gesture, was it not?

Both parties came to an agreement in June 2000, according to which…

- The meteorite would remain in New York City, in the American Museum of Natural History’s brand-new Frederick Phineas and Sandra Priest Rose Center for Earth and Space.

- No piece would be cut from the meteorite from that point onward,

- Indigenous people would be able to conduct a private ceremony around the meteorite once a year,

- The museum agreed to put up a prominent panel explaining the spiritual significance of the meteorite,

- Ownership of the meteorite would be transferred to the CTGR should the museum take it out of display.

The museum may also have launched an internship program aimed at Indigenous people around that time.

If you must know, Rose was an American real estate developer and philanthropist.

It is worth noting that when dealing with Indigenous representatives, certain staff members of the American Museum of Natural History, while civil, were not necessarily cooperative. And yes, the museum had / has in its collections more than a few objects these representatives wanted to see returned to their original / rightful owners.

In April 2006, a 130 or so grammes (4.5 ounces) fragment of the meteorite in the possession of the Macovich Collection of Meteorites, the largest and most famous private collection of (iron?) meteorites on planet Earth, was bought at auction by a person or group and put on display at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, in McMinnville, Oregon. Said fragment was given to the CTGR in February 2019.

In 2007, the 13 or so kilogramme (28 pounds) section of the meteorite which had been traded, around 1997-98, to the Macovich Collection of Meteorites, in exchange for a Martian meteorite, was scheduled to be auctioned. That piece of news did not go unnoticed. Oregon Indigenous groups were deeply saddened by what they described as the sale of a sacred and historic artifact. An offer made at some point by the Macovich Collection of Meteorites to sell the fragment to the American Museum of Natural History, which would donate it to the CTGR, was politely turned down. Indigenous groups stated that they simply could not negotiate or barter for objects deemed to be sacred.

An article published in the most important newspaper in Portland, The Oregonian, soon asserted that the CTGR would file a lawsuit against the new owner of the meteorite fragment. The CTGR, which may not have been contacted beforehand, denied it intended to sue anyone. It even had no intention to stop the auction from taking place. Somewhat contrite, the newspaper published an apology. By then, of course, the damage had been done. Several potential bidders chose not to take part in the proceedings. In the end, the auction house withdrew the fragment from sale when bids failed to reach, and by far, the minimum sum it had put forward.

Responding to the request of a student, Oregon state representative John Lim, born Lim Yong-geun, introduced a resolution in (March?) 2019 demanding that the American Museum of Natural History return the meteorite to Oregon. The CTGR, which had not been contacted beforehand and was happy with the agreement it had reached with the museum, did not support the resolution. There was a vote and the resolution was sent to a committee which seemingly chose to let the matter drop.

And that is it for today, my faithful if slightly masochistic reading friend. Stay safe, away from the clamour of the streets, and, if I may quote, out of context, journalist Ned “Scotty” Scott, one of the supporting characters in a classic of cinematographic science fiction, The Thing From Another World of 1951, watch the skies, everywhere! Keep looking. Keep watching the skies!

And yes, any meteorite found on Canadian soil belongs to the owner, either private or public, of the property where it is found. Given the number of very legitimate Indigenous land claims, that ownership may not be as clear as one might think.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)