“Petrol will never kill electricity, especially if the latter is defended by a Kriéger.” Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger and his electric automobiles, including some of the first hybrid vehicles on planet Earth, part 2

Welcome aboard, my reading friend fascinated by the French engineer Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger and his electric and hybrid automobiles. Let us resume our look at that exciting story without any further ado.

In the United Kingdom, the firm which represented the interests of Kriéger and the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques, British & Foreign Electrical Vehicle Company Limited, took part in the electric automobile competition organised in November 1900 by the Automobile Club of Great Britain. A Kriéger type vehicle known under the name Powerful was, with an English vehicle, the one which did best during all the tests, spread over 4 days, in difficult terrain and bad weather.

Would you believe that a Canadian firm took part in that competition? Yes, yes, Canadian. Canadian Electric Motor Company of Toronto, Ontario, manufactured the vehicle in question. The brain behind said vehicle was an Anglo-Canadian engineer / inventor by the name of William Joseph Still.

Yes, yes, that Still, the one honoured by a stamp issued in June 1996 by Canada Post Corporation. Still had manufactured the first Canadian electric automobile, in 1893, for a patent lawyer, Frederick Barnard Fetherstonhaugh of Mimico, Ontario. (Hello, EP!)

The Canadian vehicle did not behave particularly well in the 1900 competition, by the way.

You will obviously remember, my avid reading friend which you are, that Kriéger gave himself a small gift in 1899, in this case the Électrolette, a fast and powerful 2-seater car.

As you might imagine, the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques presented that Electrolette to the general public as part of the Exposition universelle de 1900, held in Paris, France, between April and November.

At the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in that same city in January and February 1901, Kriéger had the honour of describing the first French electric postal vehicle to the Minister of commerce, industry, and posts and telegraphs, Alexandre Millerand. That vehicle using the technology developed by Kriéger was, however, seemingly manufactured under license by another firm, the Société l’Électrique, for all intents and purposes owner of the Société française d’automobiles électriques from 1901 onward, I think, and…

Yes, that Société française d’automobiles électriques, the one whose name I asked you not to forget in the 1st part of this article.

Would you believe that the Gallia brand vehicle which we have just come across carried the mail of the French President, Émile François Loubet, and the Tsar of Russia, Nikolai II, born Nikolai Aleksandrovich “Nicky” of house Romanov, while they attended a military review, at the Bétheny camp, not far from Reims, France, in September 1901?

Nikolai II and his spouse, Tsarina Aleksandra Feodorovna “Alix” Romanova, née Princess Alix Viktoria Helene Luise Beatrix of house Hessen und bei Rhein, were then making a brief official visit to France, in order to strengthen the essential Franco-Russian alliance.

Let us not forget, the Russian Empire and France, two countries which could not be more different, had respectively ratified a secret military convention in December 1893 and January 1894 according to which they would come to each other’s aid in the event of a German attack. Adversity really makes strange bedfellows. In any event, that secret convention had been publicly confirmed in August 1897, but back to Kriéger.

Um, yes, you are right, my reading friend, the Tsarina was indeed mentioned in an August 2023 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Her spouse, for his part, was so mentioned a few times since December 2018.

The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques having hardly appreciated certain practices of the aforementioned Société française d’automobiles électriques, it withdrew its production rights and sued in August 1901. It won its case. The management of the Société française d’automobiles électriques appealed that judgment, however. That legal saga only ended in May 1906, with the victory of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques, but back to the year 1901 and our story.

It was during the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports of December 1901 that a Kriéger coupe, in other words a fixed roof Kriéger automobile, I think, was “presented” to the King of the Belgians, Léopold II, born Léopold Louis-Philippe Marie Victor of house Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha, a very unpopular monarch in many circles. You see, the subordinates of Leopold II had governed with unspeakable cruelty the État indépendant du Congo, his personal, yes, yes, personal property, I kid you not, and this between 1885 and 1908.

Yours truly unfortunately does not know if that vehicle was presented or given to that rather unsavory king who never had to pay for those crimes against humanity, to quote the expression used as early as 1890 by the African American amateur historian / journalist / lawyer / Baptist minister / politician / soldier George Washington Williams.

Now let us move on.

Allow me to mention that Prince Ibrāhīm Ḥilmī Pāshā, one of the uncles of the Khedive / Viceroy of Egypt and Sudan, ‘Abbās Ḥilmī II of house Alawiyya, acquired a Kriéger 4-seater electric landaulet no later than October 1900. That vehicle, an automobile whose rear seats were covered by a convertible top, I think, may very well have been the first electric automobile to have rolled in Egypt. Between 1900 and 1904, that prince also acquired a 2-seater Kriéger electric coupe for gala outings.

Another uncle of ‘Abbās Ḥilmī II, Ḥusayn Kāmil Pāshā, received two vehicles from the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques between 1900 and 1904, the first one electric and the second hybrid.

In October 1901, Kriéger set a world distance record for an electric vehicle by traveling from Paris to Chatellerault, France, in the company of Georges Prade, a French sports journalist and editor of the Parisian sports daily L’Auto-Vélo. He covered that distance, 307 or so kilometres (191 or so miles), in 17 hours 35 minutes, without having to recharge the batteries of his Électrolette.

It should be noted that those 17 hours 35 minutes included a certain number of stops and backtracks due to route errors or sections of road that were too dangerous for the Électrolette’s tires. Kriéger and Prade thus lost around 2 hours 20 minutes. I kid you not.

Mind you, Kriéger and / or the staff of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques might, I repeat might, have secretly introduced a chemical into the Electrolette’s rechargeable batteries, in order to improve its performance. This at least was what the boss of the Société anonyme des voitures électriques A. Védrine, a certain… A. Védrine, would later state.

In turn, the editor-in-chief of the Parisian magazine L’Industrie électrique, the French engineer / professor Édouard Hospitalier, believed that the rechargeable batteries were tampered with in another way.

Kriéger vehemently denied those allegations.

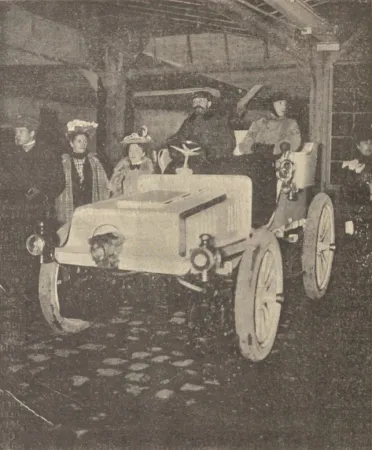

Before I forget, the photograph at the very beginning of the 2nd part of this article showed Kriéger and Prade a few moments before the beginning of their journey.

An American financier apparently purchased their Électrolette in June 1902. Joseph H. Hoadley was said to have paid the modest sum of 50 000 francs for that powerful and fast vehicle. By the way, that sum corresponded to approximately $330 000 in 2024 currency. Wah!

And yes, Hoadley was mentioned in the 1st part of this article.

In the United Kingdom, in June 1901, the aforementioned British & Foreign Electrical Vehicles Company Limited oversaw a round trip of just over 150 kilometres (95 or so miles) between London, England, and Reading, England. The vehicle used to do that, painted white and equipped with English rechargeable batteries, was known as the Powerful. Yes, again.

The English firm went one better in August and September, overseeing a road trip of 1 775 or so kilometres (1 100 or so miles) from London, England, to Glasgow, Scotland, with a return trip to London. Wah!

Between the end of May and the end of July, the Powerful actually travelled a little over 2 950 kilometres (nearly 1 850 miles) on British soil with 4, and sometimes even 5, people on board.

Incidentally, the management of British & Foreign Electrical Vehicles had organised the trip to Glasgow in order to participate in the Glasgow International Exhibition which was held between May and November 1901.

The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques also delivered an electric automobile to the English firm during the fall of 1901. Used during the round trip organised in November by the Automobile Club of Great Britain between London and Southsea, England, a very popular seaside resort, that vehicle behaved very well, a performance which certainly did not go unnoticed.

It went without saying that all those peregrinations took place in very varied weather conditions and on very varied routes, the United Kingdom being of course known for its idyllic climate.

According to many observers, all those performances demonstrated that the electric automobile was finally ready. It truly was the vehicle of the future. Easy to maintain and with a good range, the Electrolette was a relatively inexpensive example of that type of vehicle.

The term relatively was very important here. Indeed, the electric vehicles of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques were not within the reach of all budgets. Just think of the magnificent and powerful olive green 4-seater landaulet delivered in 1901, or at the very beginning of 1902, to a German banker who died shortly after taking delivery. Said banker had paid the modest sum of 18 000 francs, or approximately $120 000 in 2024 currency. Wah!

A typical electric coupe of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. That vehicle was probably very similar to the electric fiacres which circulated in the streets of Paris. Gérard Lavergne, “L’automobile en 1902 – Quatrième partie: Voitures électriques et mixtes.” Revue générale des sciences pures et appliquées, 30 October 1902, 976.

Many less wealthy Parisians, both female and male, could nevertheless experience the olfactory and auditory comfort offered by the electric vehicles produced by the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. Would you believe that, at the end of 1902, more than 300 red painted (Kriéger?) electric fiacres circulated every day in the streets of Paris, offering said Parisians a much appreciated odorless and noiseless service? Things had changed a lot since 1900, it seemed.

It was apparently in May 1902 that the first hybrid vehicle designed by Kriéger appeared in public, more precisely as part of the Concours de véhicules automobiles à l’alcool organised in Paris by the Ministère de l’agriculture. Said vehicle, a phaeton, in other words a two-seater open automobile, I think, was the only voiture mixte / voiture pétroléo-électrique, two French expressions used more or less frequently at the time, which participated in the competition. That vehicle, quite possibly the very first hybrid vehicle running on alcohol, could approach 50 kilometres/hour (more than 30 miles/hour), it was said, on a good, straight road.

And yes, yours truly assumes that the piston engine of that hybrid vehicle could also burn gasoline, if modified for that purpose.

And yes, again, the Ministère de l’agriculture probably organised that competition to lend a hand to the French wine industry, a large productor of alcohol before the lord.

A brief digression of a technical nature if I may. Kriéger’s hybrid vehicle had a piston engine operating a dynamo in addition to its rechargeable batteries and its pair of electric motors, one for each front drive wheel. There was no mechanical connection between the piston engine and the driving wheels of the vehicle, however.

Although the piston engine / dynamo assembly could send a bit of electric fluid to the rechargeable batteries while said vehicle moved on a flat surface, it was especially in descents that the rechargeable batteries charged up.

By the way, the Kriéger hybrid vehicle was the subject of all conversations among Paris automobile enthusiasts. For many, that type of automobile was the formula of the future. Unlike the electric automobile, confined to Paris due to the absence of a network of charging stations in the provinces, it could actually set off into the countryside.

Indeed, in June, Kriéger used his hybrid vehicle to travel to Bruxelles / Brussel / Brussels, Belgium, a nice trip of 400 or so kilometres (250 or so miles), completed in just over 17 hours, most of it on unpaved roads. History did not say whether he made the return trip at the wheel of that same vehicle, however.

Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger at the entrance to the stand of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques at the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports, Paris, France. Édouard Pontié, “Le 5e Salon du Cycle et de l’Automobile.” Le Sport universel illustré, 21 December 1902, 814.

The Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques exhibited a hybrid vehicle slightly different from the one mentioned above during the Salon de l’automobile, du cycle et des sports held in Paris in December 1902.

There was still no mechanical connection between the piston engine and the drive wheels of that new vehicle, of course, but it no longer had rechargeable batteries, which considerably reduced its weight. You see, the piston engine now activated a dynamo which powered the 2 electric motors which turned the vehicle’s drive wheels.

That hybrid vehicle was said to be able to reach 70 kilometres/hour (almost 45 miles/hour) on a good, straight road.

Kriéger might, I repeat might, have driven at least one example of that improved vehicle with a more powerful engine from Paris to Brittany and to Normandy in order to check its reliability.

It was in front of that type of vehicle and in front of the magnificent electric automobiles present in the firm’s stand that the French President stopped for long minutes. Yes, yes, the French President. The aforementioned Loubet asked many questions, to the great joy of Kriéger.

It went without saying that Loubet probably visited other stands during his visit.

Rumours circulated at this time according to which a major French automobile manufacturer was seriously considering joining forces with Kriéger to launch large-scale production of his hybrid vehicle, and…

You have a question, do you not, my reading friend? Let me guess. Was Kriéger the first Homo sapiens to develop a hybrid vehicle? To make a long story short, a rarity in these pages I freely admit, no.

The first hybrid vehicle to run on Earth appeared to be a unique and advanced vehicle designed by a brilliant American designer, Harold E. “Harry” Dey, for Roger American Mechanical Carriage Company, an American firm specialising in the importation of gasoline automobiles produced in France by Roger & Compagnie. Said vehicle, a phaeton, was manufactured in 1896 by another American entity, however, Armstrong Manufacturing Company.

The management of Roger American Mechanical Carriage was so impressed by Dey’s hybrid vehicle that it founded American Horseless Carriage Company to market it.

For some reason or other, however, both Roger American Mechanical Carriage and American Horseless Carriage had to close up shop before 1896 was even out.

As you might imagine, several other hybrid vehicle prototypes hit the road in Europe and America, yes, the continent, over the following years. And no, my patriotic reading friend, as far as yours truly can tell, none of those hailed from Canada. Sorry.

The first series-produced hybrid vehicle, on the other hand, apparently saw the light of day in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. That story began in 1899 when Ludwig Lohner, the boss of König- und Kaiserlichen Hof-Wagen-Fabrik Jacob Lohner & Compagnie, saw a hybrid vehicle manufactured by a Belgian firm, the Anciens establishments Pieper Société anonyme, at the Internationale Motorwagen-Ausstellung which was held in Berlin, German Empire, in September.

Intrigued, Lohner asked a brilliant young Austro-Hungarian engineer who was more or less self-taught to design a similar vehicle. Ferdinand Porsche supervised the manufacture of the Lohner-Porsche Semper Vivus in 1900 and…

Yes, yes, that Porsche. The one who designed, between 1933 and 1938, with some help, the German compact automobile known as the KdF-Wagen, a mythical vehicle known after the Second World War as the Volkswagen Type 1, or Kafer / Beetle / Coccinelle.

The acronym KdF obviously meant Kraft durch Freude, in English Strength through Joy. That movement was a large leisure organisation within the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, the German workers’ and employers’ organisation created in 1933 by Adolf Hitler’s Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, but back to Porsche’s hybrid vehicles.

A second version of the Austro-Hungarian hybrid vehicle left the workshops in 1901, but it was soon put aside. Two other improved versions appeared in 1902 and 1903. Those vehicles gave birth to a production vehicle, the Lohner-Porsche Mixte, I think. That hybrid vehicle was said to be able to reach 90 kilometres/hour (more than 55 miles/hour) on a good, straight road. Wah!

König- und Kaiserlichen Hof-Wagen-Fabrik Jacob Lohner & Compagnie might, I repeat might, have produced around 300 Mixtes, but back to Kriéger.

The King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele III, born Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro of house Savoia at the wheel of the royal couple’s Kriéger victoria. His spouse, the Queen of Italy, Elena del Montenegro, born Jelena of house Petrović-Njegoš, was at his side. Anon., “LL. Majestés le Roi et la Reine d’Italie dans leur victoria électrique Kriéger.” La Vie au Grand Air, 12 May 1904, 363.

Before I forget, let me point out that, around mid-August 1903, Kriéger went to Italy to personally deliver one of his electric automobiles to the King of Italy. Having absorbed Kriéger’s explanations, Vittorio Emanuele III, born Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro of house Savoia, took the wheel of that 2-seater victoria, in other words of that open automobile, and strolled through the magnificent park of the Racconigi / Racunìs palace in the company of his spouse.

Mind you, at least one source suggested that it was this Queen of Italy, Elena del Montenegro, born Jelena of house Petrović-Njegoš, who had ordered the vehicle in question.

By May 1904 at the latest, members of the Spanish (Borbón y Austria), Russian (Romanov), Italian (Savoia), Egyptian (Alawiyya), Danish (Glücksburg), British (Saxe-Coburg and Gotha) and, perhaps, Belgian (Saxe-Cobourg et Gotha) royal families owned at least one vehicle from the workshops of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. Impressive, was it not?

A Russian royal vehicle belonged to Grand Duke and General Admiral Alexei Aleksandrovich of house Romanov and... Yes, yes, that Grand Duke, the one who had spent several days in Québec and Ontario in December 1871. He was not yet 22 years old and seemed very impressed by the Niagara Falls, but I digress.

And while we are at it, why not add that another Russian royal vehicle belonged to Prince Vladimir Nikolayevich Orloff and... Yes, yes, that prince, the one who introduced the aforementioned Nikolai II to the pleasures of an automobile ride, in 1903.

Before I forget, Vittorio Emanuele III took possession of an electric coupe in September 1905. He and his spouse used it as passengers. The Italian king loved both of his Kriéger vehicles.

Another royal client was added to this list around October 1905. Sultan Abd Hamid II, born Abd ul-Hamid-i s̱ānī of house Osmanoğlu, sovereign of the Ottoman Empire, actually renounced a little his hostility towards automobile locomotion and most things modern, and took possession of an electric vehicle. He apparently only used it in the gardens of Yildiz Sarayi, his palace in Istanbul, Ottoman Empire, however.

And yes, Abd Hamid II was an unsavory monarch who never had to pay for his crimes against humanity, namely the massacres of 1894-96, which caused the death of 225 000 innocent people, if not more, the huge majority of Armenian origin.

Now let us move on.

Let me mention that the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, born Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio of house Borbón y Austria, became the proud owner of a Kriéger electric vehicle no later than 1906, I think. You remember of course, my faithful reading friend that you are, that this sovereign was mentioned in December 2017, June 2020 and November 2020 issues of our essential blog / bulletin / thingee.

A brief digression if I may. Members of Alfonso XIII’s entourage had a good scare in February 1909 when he placed his royal posterior next to that of Wilbur Wright, in Pau, France, when the latter showed him the controls of a Wright Flyer. The King of Spain, then aged 22, was cruelly tempted to take to the air with that famous American aviation pioneer.

Wright, as you probably know, has been mentioned many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since December 2017.

Ending this second part of our review of the achievements of a French electric and hybrid automobile manufacturer by mentioning one of the Wright brothers was not something yours truly had intended, but it works for me. See you soon.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)