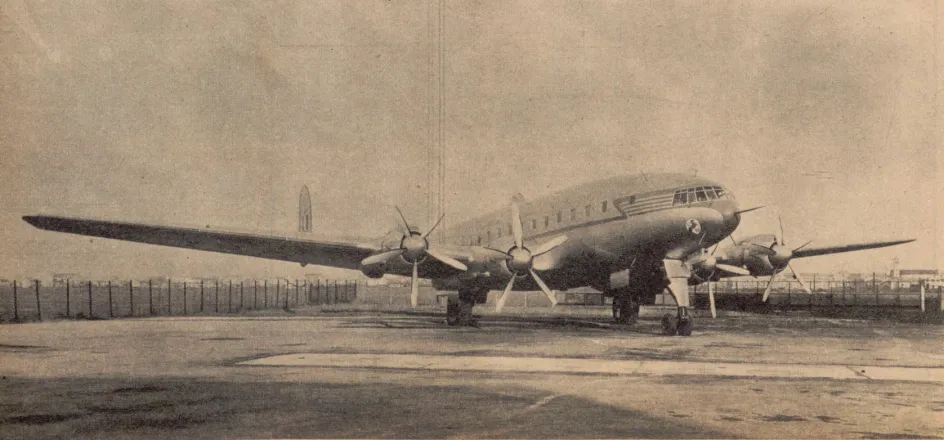

Il Constellation italiano, an unrecognised star in Italy’s aeronautical firmament: The Breda Zappata BZ 308 long range airliner

It is with a certain trepidation that yours truly approaches the subject of this week, my reading friend. I feel a certain discomfort at the idea of talking about an aircraft designed in Italy during the years during which the Partito nazionale fascista, an unsavoury organisation led by Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini, a pompous brute and buffoonish dictator mentioned since August 2018 in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, held the reins of power.

Before getting to the heart of the matter, discovered in the 1 September 1951 issue of the excellent French bimonthly Aviation Magazine, allow me to pontificate for a brief moment on the chief designer of the Breda Zappata BZ 308 long range airliner.

Filippo Zappata, one of the best Italian aeronautical engineers of the 20th century, was born in July 1894. Wishing to become a naval engineer, he began studies at the Regia Scuola d’Ingegneria Navale. Zappata was seriously injured while serving during the First World War, in 1917, however. Once recovered, in 1918, he was assigned to military technical services.

After the end of the conflict, Zappata began a career in aeronautical engineering. He first worked for Società anonima Gabardini per l’Incremento dell’Aviazione where he soon became deputy technical director. His employer preferring the traditional concepts of his superior, Zappata joined the staff of French aeronautical giant Blériot Aéronautique Société anonyme, a sister / brother firm of the Société anonyme des Établissements L. Blériot, around 1929.

And yes, both Blériot Aéronautique and Établissements L. Blériot were mentioned in a May 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but I digress.

The first aircraft that Zappata realised, the Blériot 110, or Blériot-Zappata 110, became famous as a record machine. In February-March 1931, Jean Baptiste Lucien Boussotrot and Maurice Rossi set new closed circuit world records for distance (8 805 kilometers / 5 471 miles) and flight time (75 hours 23 minutes). In March 1932, that same dynamic duo set another closed circuit world record for distance, 10 605 kilometers (6 590 miles). In August 1933, Paul Codos set a world distance record with Rossi flying from New York City, New York, to Rayak, Lebanon – a distance of 9 104 kilometers (5 657 miles).

Contacted perhaps, I repeat perhaps, by the Italian air minister, Italo Balbo, a brute with the looks of a movie star mentioned in August 2018 and December 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, Zappata returned to Italy in the summer of 1933. An important shipyard involved in aircraft construction, Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico Società anonima, offered him the post of chief aeronautical engineer. Zappata specialised in designing excellent seaplanes primarily for the Italian air force, the Regia Aeronautica. Well-known Italian crews flying these aircraft set several records for altitude, distance and speed during the 1930s.

Very concerned about the poor quality of the aircraft designed for a certain time by its engineers, the management of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche offered Zappata the post of chief aeronautical engineer at the beginning of 1942. Aware of the importance of this firm which worked in the railway and aeronautical fields, somewhat disappointed by the performance of Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico for a certain time and in search of new challenges, Zappata accepted.

The disintegration of the Italian war machine, which culminated with the signing of an armistice with the Allies, in September 1943, and the subsequent occupation of the Italian peninsula by National Socialist Germany, allied with the submission of the Italian war industry to the desiderata of the German occupier and the almost total destruction of the aeronautical factory of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche, in April 1944, by bombers of the United States Army Air Forces, ensured that none of the new projects launched by Zappata took to the sky during the Second World War.

One of said projects was a long range airliner, the BZ 308, in other words the aircraft that concerns us today, which Zappata began to focus on even before the end of 1942. If yours truly may be permitted a comment, one might wonder why the engineer embarked on that adventure. Submitted to the needs of the increasingly desperate Italian government, the Italian national air carrier, Ala Littoria Società anonima, had other fish to fry.

This being said (typed?), the staff of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche may, I repeat may, have completed the fuselage structure of the prototype of the BZ 308 before the signing of the armistice of September 1943. Once informed of the firm’s activities, the German occupier prohibited further work on the aircraft.

The unconditional surrender of National Socialist Germany, in May 1945, resulted in the substitution of a most brutal German occupation by a much more humane Allied, read Anglo-American, control. This being said (typed?), however, the Allied Commission put the kibosh on all Italian aeronautical projects until early 1946.

Faced with this cease and desist, the staff of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche had to put its tools aside for several months. It completed the prototype of the BZ 308 during the summer of 1946. It is possible that the Allied Commission put the kibosh on the work, which did not resume until early 1947.

If so, the staff of the firm completed the prototype of the BZ 308 during that same year. Well almost. You see, the Engines Division of Bristol Aeroplane Company Limited, a well-known British firm mentioned in several issues of our you know what since June 2018, did not deliver the engines the BZ 308 needed until 1948.

A suspicious person, not I or you of course, might wonder if the delay was caused by a request from the British government, or a refusal by the latter to grant an export permit. Why would the British government do this, you ask? Our suspicious person might suggest that the British government did not want an Italian airliner to capture a share of the airliner market at the expense of new aircraft offered by British aircraft manufacturers.

Indeed, Zappata and his team had considered since at least 1947 the possibility of offering their future customers the possibility of using engines designed by 2 American aeronautical giants, the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Division of United Aircraft Corporation and the Wright Aeronautical Division of Curtiss-Wright Corporation. A detail before I forget: the engine nacelles of the BZ 308 were accessible in midflight.

And yes, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and United Aircraft were mentioned several / many times in our you know who since August 2017. Wright Aeronautical and Curtiss-Wright, on the other hand, have been mentioned there several / many times since February 2018 and November 2017.

Another detail before I forget: the new long range airliners offered by said British aircraft manufacturers were the Avro Tudor and the Handley Page Hermes, which went into service in the fall of 1947 and the summer of 1950. The former was no great shakes. From the looks of it, less than 10 Tudors and 25 Hermes carried passengers. The Bristol Brabazon was even worse. That ginormous flying dinosaur flight tested in September 1949 never entered service. And yes, the Québec-made Canadair North Star pretty much saved the day, as did American long range airliners like the Lockheed Constellation and Boeing Stratocruiser.

At the risk of falling into the dark and paranoid world of conspiracies, a Polish daily, the most important one in fact, Trybuna Ludu, asserted around 1948-50 that the delay in the delivery of the BZ 307 engines was the result of a discreet Anglo-American operation having aim to oust a potential competitor. Better yet, the American government allegedly asked the president of the Italian Cabinet, Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi, to have employees of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche laid off in order to delay the completion of the BZ 308. Although it admitted that such interventions were possible, the Italian press nonetheless pointed out that Trybuna Ludu was published in a country under Soviet domination, and ...

You have a question, don’t you? How could a Polish journalist get wind of a more or less secret meeting involving De Gasperi? The fact was that the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI) was very influential at the time and had supporters almost everywhere. Such a supporter may have informed the party, which informed a member of the Soviet embassy, which informed the Soviet government. Aware of its lack of credibility among large segments of the Italian population, the latter may have passed the information on to the Polish government, which informed the leadership of Trybuna Ludu. All of this was obviously very conjectural, and very possible.

Let us not forget, the American government was, perhaps, equally aware of its lack of credibility among large segments of the Italian population. A good part, if not the majority of the servants of the state in place before the fall of the aforementioned Partito nazionale fascista, including unsavoury figures in the armed and police forces, remained in place after its fall. Worse still, the American government did not denounce the systematic refusal of the Italian government to allow the governments of countries such as Yugoslavia and Ethiopia to obtain the extradition of several Italians so they could be brought to justice for war crimes.

Would you believe that some very influential elements of the American government were thinking of encouraging and supporting a military coup if the Fronte Democratico Popolare per la libertà, la pace, il lavoro, a left of centre coalition of the PCI and the Partito Socialista Italiano, won the elections of April 1948? Discussions to that effect ended following the victory of a center-right / right-wing party, Democrazia Cristiana, following a campaign in which the American government intervened in total disregard of democracy, but I digress.

Late delivery of the engines was not the only problem that Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche faced. Its tooling was somewhat obsolete. It also experienced more or less serious difficulties in getting its hands on top quality materials. Worse yet, the firm’s serious financial problems did not always allow it to buy what it needed when it needed it. And even when these materials were available and the tools were working, the Italian electricity network was not always of exemplary reliability.

By the way, the cafeteria of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche was apparently one of the few in the region where white collar and blue collar workers could eat together. In fact, in the eyes of many workers in various industries in the region, the BZ 308 pretty much became a symbol of their knowhow and a source of hope for the future. Some even dared to claim, it was said, that it was a… communist airplane.

And no, the Italian government headed by De Gasperi provided virtually no financial support for the project. It did not facilitate the acquisition of new tools or materials either. Such indifference may be surprising, or not, given the fact that said government was to all intents and purposes the owner of Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche, through the Fondo per il finanziamento dell’Industria Meccanica (FIM), an organisation created in 1947 to finance the conversion of firms engaged in military production during the Second World War. While many Italian firms managed to recover and repay the loans granted by the FIM, Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche simply could not.

You ask yourself if the discreet Anglo-American operation having aim to oust the BZ 308 was / is more than an urban legend, my reading friend? Me too.

In any event, the BZ 308 first took to the air in August 1948. As was his custom, Zappata was on board to observe the behaviour of his creation.

Would you believe that De Gasperi and other members of the government, not to mention senior military officials, were present at the first flight of the BZ 308?

This elegant aircraft was quickly nicknamed the Italian Constellation because of its resemblance to the aforementioned Constellation.

The BZ 308 could carry approximately 50 passengers on transatlantic flights, or up to approximately 80 passengers on continental flights. Its fuselage could also accommodate humans and cargo – approximately 30 passengers and 3 or 4 tonnes (3 or 4 Imperial tons / 3.3 or 4.4 American tons) of cargo.

Keen to improve his aircraft’s chances of success, Zappata prepared plans for a pressurised version of the BZ 308 – an innovation which allowed flying humans to breathe unhindered at an altitude which maximised the performance of an airliner’s engines.

Oddly enough, Zappata also prepared plans for a twin-float version of the BZ 308. The floats on this machine were designed to be accessible in mid-flight. They also contained storage spaces for freight. According to Zappata, a seaplane offered greater safety during transoceanic flights.

Neither of these versions went beyond the drafting table or the model stage.

And yes, you are quite right, my wing nutty reading friend. The Constellation, or “Connie,” had been carrying passengers from one side of the Atlantic Ocean to the other since February 1946. The crew of a Douglas DC-4, another American long range airliner, had crossed that same ocean with dignitaries and journalists in October 1945.

Available as war surplus, the Constellation, ex-Lockheed C-69 Constellation, and the DC-4, ex-Douglas C-54 Skymaster, soon took up a large share of the market. Brand new Constellations and DC-4s soon joined them. It should also be noted that the first example of a more modern and powerful derivative of the DC-4, the Douglas DC-6, was delivered in November 1946.

Confronted with these magnificent, well-proven machines, the BZ 308 stood little chance of breaking through.

By the way, as 1946 drew to a close, rumours were circulating that an Italian airline, Linee Aeree Italiane Società per azioni (LAI) or Aerolinee Italiane Internazionali Società per azioni in all likelihood, was apparently considering ordering 6 aircraft which would enter service after the signing of a peace treaty by the governments of Italy and allied countries.

Said treaty, the Treaty of Paris, was signed in February 1947. Indeed, that treaty was signed by 5 countries who had fought on the wrong side, in other words the losing side, during the Second World War, namely Bulgaria, Finland, Hungary, Italy and Romania, and…

Why this horrified look, my reading friend? Whatever the conflict, the losers are always wrong. As Brennus, the Gallic leader who captured Rome or, more precisely, whose troops captured Rome in 390 before the common era, said, vae victis! Woe to the vanquished!

A brief digression if I may. Expressions like “Pharaoh Khnum Khufu built the great pyramid” read and / or heard from time to time, make me laugh like a drain. I imagine that good pharaoh carrying one by one the 2.3 million blocks of stone that made up the pyramid. Assuming he had ruled for about 45 years, Khnum Khufu would have been shoving 140 blocks a day. That’s a lot of magic potion… Getafix? Asterix?? Nothing?! Really? Sigh… Let us go back to the 6 aircraft that an Italian air carrier apparently wanted to order.

A suspicious person, not me or you of course, might doubt somewhat the truth of that statement. Indeed, the major American airline Trans World Airlines Incorporated (TWA) owned 40% of the shares of LAI while the British crown corporation British European Airways Corporation (BEA) owned 40% of the shares of Aerolinee Italiane Internazionali. Pressure from representatives of TWA and BEA to buy American or British airliners was not unimaginable. And yes, LAI and Aerolinee Italiane Internazionali mainly used American airliners.

This being said (typed?), rumours circulated in the fall of 1949 that an order from an Italian air carrier was still held. It was still mentioned in the middle of 1950. Better yet, other rumours circulated in the fall of 1949 concerning an Argentinian order, for 3 or 4 aircraft it seems, perhaps destined for the national air carrier Aerolíneas Argentinas Sociedad anónima. Indeed, Zappata went to Argentina around 1947 to negotiate that order. Better yet, when he came back, he had a licensed production project in his pocket involving Argentina’s only aircraft manufacturer worthy of the name, state-owned Fábrica Militar de Aviones.

Still other rumours circulated in 1949-50 that air carriers of India and Iran and, perhaps, Israel and Norway, other words Air India International Limited and Iran Airways Company as well as El Al Aviation Company and Det Norske Luftfartselskap Aksjeselskap, envisioned to contemplate purchasing BZ 308s.

That interest was due in part to the fact that the management of said carriers was questioning whether the American aircraft industry would be able to meet the enormous increase in demand for airliners capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Additionally, not everyone wanted to depend on the American aircraft industry for their airliner needs.

None of these potential orders led to anything concrete.

Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche ultimately had to resign itself to sell the one and only BZ 308 to the Italian air force, the Aeronautica Militare, in August 1951.

The firm’s financial situation was then so serious that a state-imposed administrator ordered the closure of all its aeronautical workshops, except one, which was transferred to another firm. In 1952, Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche became a holding firm, Finanziaria Ernesto Breda Società per azioni.

And what happened to the BZ 308, you ask yourself, my reading friend who wishes this endless pontification to end? What happened to it can be summed up in a few words. Well, in many paragraphs in fact.

The BZ 308 made a series of flights to the United Kingdom around 1952 and appeared as an Italian extra in the excellent American film Roman Holiday, which was released in theatres in 1953. It was indeed from the BZ 308 that disembarked the agents of an unidentified European country whose mission was to find the young crown princess of said country, who had temporarily run away in Rome because she was sick and tired of her overly regimented life. And yes, it was the lovely British actor Audrey Hepburn, born Audrey Kathleen Ruston, who starred as princess Ann.

In October 1953, the BZ 308 became one of the aircraft used to transport the personnel of the Amministrazione Fiduciaria Italiana della Somalia (AFIS), as well as their families. Said administration, created in 1950 under the aegis of the United Nations Organization (UN), was to facilitate the transition to independence of Italian Somalia, an African territory conquered, occupied and colonised in brutality between 1889 and 1941. And yes, as incredible as it may seem, the UN was allowing the Italian government to prepare the independence of its former colony.

Incidentally, Italian Somalia and British Somaliland merged in July 1960 to form Somalia.

A brief digression if I may. Even though the conquest, occupation and colonisation of British Somaliland was far less bloody than that of Italian Somalia, it was not all that rosy for the local populations. A resistance movement rose which fought the British occupier for 20 years. It was crushed within the space of 6 weeks, in January and February 1920, as a result of a well-prepared and coordinated assault launched by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and African units of the British Army.

The former’s “shock and awe” method proved so effective, in theory, and cheap, that it became the method of choice of British governments to crush local resistance movements in places like Palestine, Mesopotamia (Iraq) and India, in this case the North West Frontier Province, during the 1920s and 1930s. One could argue that the RAF’s success in British Somaliland and elsewhere helped to save it from being torn asunder and absorbed by the British Army and Royal Navy.

One of the RAF officers who served in these faraway lands was Arthur Travers “Bomber / Butch / Butcher” Harris, the commanding officer of the RAF’s Bomber Command between February 1942 and September 1945.

More or less similar “Shock and awe” methods have been / are being used by the United States since 2001, through unpiloted aerial vehicles, in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen. Between 900 and 2 200 civilians may have died in these attacks as of 2021. End of digression.

The BZ 308 made its first flight to Italian Somalia in October 1953. That odyssey was marred by a failure of the hydraulic system and a higher than expected fuel consumption. As the crew examined the aircraft in order to return to Italy, the director of AFIS lobbied the Ministero della Difesa and Ministero degli Affari esteri to obtain permission to borrow the BZ 308 to offer himself a little vacation in Madagascar, then a French overseas territory. Enrico Martino got what he asked for.

The BZ 308 flew to Madagascar in October 1953 but had to land in Tanganyika, today’s Tanzania but then a British-administered territory under UN control, because of bad weather. A tire having burst, the aircraft left the runway. A propeller and a wing were damaged.

Once repaired, the BZ 308 returned to Italian Somalia in November. With Martino’s little vacation no longer a priority, it flew to Rome a few days later. The list of passengers included a lion destined for the Giardino zoologico di Roma.

Less than 2 hours after take-off, one of the engines gave way, resulting in a return to square one. As the engine damage was serious, the ground crew had to use a winch or crane to carry it to a workshop. Poorly maintained and / or overwhelmed by the weight of said engine, that piece of equipment gave way. The engine crashed heavily to the ground. Lady rumour had it that, in a scene reminiscent of a clip from a farce by Canadian-American film actor, director, producer and studio head Mack Sennett, born Michael Sinnott, the pilot of the BZ 308 was so incensed that he chased the chief of the technical staff all the way to his home, where the latter barricaded himself.

Do I need to point out that Sennett was mentioned in November 2018 and December 2019 issues of our… All right, all right, let’s not get angry – an expression which corresponds to the title of the English language version of a popular French cop comedy with few if any cops which arrived in movie theatres in April 1966.

With the damaged engine now beyond repair, the BZ 308 was not ready for flight again until February 1954. The test flight went well. As the aircraft was about to touch down, the pilot was distracted by workers running across the runway. The tip of the left wing of the BZ 308 struck a concrete mixer used to repair said runway and was torn off. The structure of the wing itself was also damaged.

The pilot and ground crew suggested removing the right wing tip from the BZ 308 in order to return to Italy at low speed. Aeronautica Militare officers rejected that suggestion and recommended that the aircraft be abandoned.

Shortly after the announcement of that decision, all the seats in the BZ 308 were removed to fit out the movie theatre of the airport at Muqdisho / Mogadishu, which was widely patronised by the Italians who lived in Italian Somalia. All usable parts and accessories, on the other hand, were removed by the staff of the Ciidanka Cirka Soomaaliya, the air service of Italian Somalia. The BZ 308 as such was dismembered. Rumours that parts of this aircraft were still visible in 1992, or even in 2006, seem unlikely.

Thus ended the story of the last long range airliner designed in Italy.

Zappata left Società Italiana Ernesto Breda per Costruzioni Meccaniche around 1951-52. Over the months and years, he politely declined many job offers, mainly from foreign firms. Around 1954, however, Zappata readily accepted to become the chief aeronautical engineer of the Italian firm Costruzioni Aeronautiche Giovanni Agusta Società per azioni. He designed a small, 4-engine short range airliner flight tested in June 1958 which did not go beyond the prototype stage. Zappata subsequently contributed significantly to the design of a large transport helicopter flight tested in October 1964 which did not go beyond the prototype stage either.

A consultant for a few years, Zappata retired in 1973. He died in August 1994, at the age of 100.

Arrivederci e ci vediamo la prossima settimana, amico di lettura.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)