“Fakes that pay off:” A brief glance at the totally fictitious nuclear-powered Soviet super bomber ‘revealed’ in December 1958 by the American magazine Aviation Week, Part 1

Yes, my reading friend well versed in the facts of life, there are fakes that pay off. You have undoubtedly heard of the counterfeiters and counterfeit money which have plagued ordinary people for centuries.

Incidentally, yours truly got saddled with a pair of fake 1 £ coins during a trip to London, England, in the late 1980s or early 1990s. The gentleman from the London Passenger Transport Board whom I asked why the ticket machine rejected those coins was kind enough to explain that fake coins were not exactly uncommon. I believe I still have one of those bloomin’ coins. Somewhere.

Would you believe that, around 2017, at least 1 in 30 of the 1 £ coins circulating in the United Kingdom was counterfeit? Wah!

And yes, counterfeit $ 2 coins made in China have been circulating in Canada since at least 2018. In very small numbers. Or so the Royal Canadian Mint says, but I digress.

You have also probably heard of the forgeries and forgers which have plagued the world of painting for centuries. Just think of the following forgers active during the 20th century:

- the West German Wolfgang Fischer, better known as Wolfgang Beltracchi,

- the Frenchman Henri Abel Abraham Haddad, better known as David Stein,

- the Englishman Eric Hebborn,

- the Hungarian Hoffmann Elemér Albert, better known as Elmyr de Hory,

- the American Mark Augustus Landis,

- the Dutchman Henricus Antonius “Han” van Meegeren,

- the Chinese Qián Péi-Chēn,

- the American Kenneth “Ken” Perenyi, and

- the Frenchman Guy Ribes.

And let us not forget one the largest art fraud cases in history, a case which involved the creation of 4 500 to 6 000 fake paintings worth tens of millions of dollars. The individual whose artwork was defrauded was the world famous Anishnaabe artist Miskwaabik Animikii, in other words Jean-Baptiste Norman Henry “Norval” Morrisseau.

Yours truly has good reason to believe that the fake about which I am going to type today is completely unknown to you, however. If this is not the case, please accept my apologies and return to this place in a fortnight.

With that warning now behind us, let us get straight to the heart of the matter, a subject linked to the upcoming inauguration of an exhibition on the Cold War at the formidable Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario. (Hello, EG and VW!)

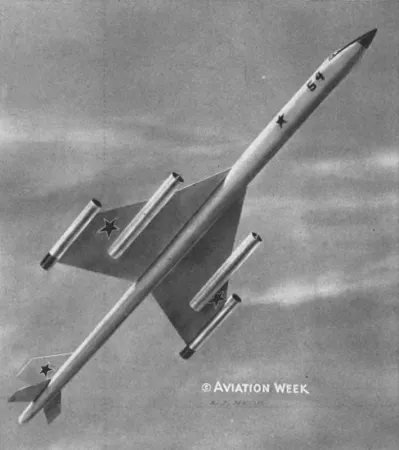

In its 1 December 1958 issue, an issue whose contents was known at least in part to the press of North America (and elsewhere?) no later than that same day, the well-known American weekly aeronautical magazine Aviation Week offered to its readership an article with a punchy title: “Soviets Flight Testing Nuclear Bomber – Atomic powerplants producing [31 750 or so kilograms] 70,000 lb. thrust are combined with turbojets for initial operations.”

The slightly supersonic military aircraft in question had made its first flight no later than September 1958, the magazine claimed. Many observers from communist and non-communist countries had seen it, whether in the air or on the ground.

Those tests were the result of a well-funded, high-priority program whose research and development origins dated back to 1950, Aviation Week believed. Work had accelerated from 1956 onward, however.

The turbojet engines mounted on the wingtips of the Soviet prototype were present for safety reasons during the preliminary test program. Subsequent versions of the aircraft could retain them for high-speed dashes, unless they were replaced by another pair of nuclear engines.

While the bulk of the preliminary tests of the new aircraft was carried out with the turbojet engines, its nuclear engines had definitely been tested in the air.

Said nuclear engines gave that machine an autonomy whose only limit was the endurance of its crew. Indeed, according to Aviation Week, a unit of mass (kilogram or pound, your choice) of a type of uranium known as uranium 235 contained as much energy as 1 700 000 units of mass of gasoline.

And no, these figures were not necessarily correct, my reading friend who likes to dot the i’s. A unit of mass (kilogram or pound, your choice) of highly enriched uranium 235 actually contains as much energy as 6 000 000 units of mass of gasoline. And it was you who digressed this time. Yes, yes, you.

Aviation Week pointed out that, unlike the American Convair B-36 strategic bomber which had been strolling since September 1955, I think, with a small nuclear reactor on board, the new Soviet aircraft was not a flying test bed intended to verify the effectiveness of its shielding against radiation, among other things. Nay. It was the prototype of a continuous airborne alert and missile launching aircraft which could enter service around mid to late 1959 at the earliest.

As such, that machine, the manufacturer of which appeared to be unknown, was the Soviet counterpart of the aircraft that two American aircraft manufacturers were hoping to develop as part of the Continuous Airborne Alert, Missile Launching and Low Level Penetration program of the United States Air Force (USAF).

And I recognise my honourable reading friend’s hand poking through the ether. Was the B-36 not known as the Peacemaker, you ask? A good question. It so happened that this moniker was apparently never officially adopted. You see, various religious groups in the United States objected more or less strongly to the use of such a name for an aircraft whose main purpose was to drop atomic bombs – and kill countless human beings.

By the way, the nuclear engine developed by the engineers of an equally unidentified Soviet design bureau was a direct cycle engine. That technology indeed offered numerous advantages (simplicity, reliability, relevance, etc.).

The air entering a direct cycle aircraft nuclear engine is compressed by a completely conventional compressor. That compressed air then passes through the core of the nuclear reactor which constitutes the heart of the engine. In doing so, it heats up considerably upon contact with said core. In return, said core is cooled by that air, which prevents it from melting. The very hot air which leaves the reactor is channeled towards a turbine which activates the aforementioned compressor. It then leaves the engine through a nozzle, producing considerable thrust.

Speaking (typing?) of melting, the shaft which connects the turbine to the compressor via the nuclear reactor core obviously has to withstand extreme temperatures and radiation. Developing an efficient cooling system was a puzzle of extreme complexity, one to which Soviet engineers seemed to have found a solution and...

Err, yes, you are quite right, my reading friend whose hair stands up straight under the effect of fright, the air which comes out of a direct cycle aircraft nuclear engine is pretty radioactive. In fact, the engine itself is highly radioactive.

Getting some fresh air near an aircraft equipped with nuclear engines if those were running on the ground would have been a very bad idea. Living downwind of a base where such aircraft would be based would also have been unadvisable.

Regarding radiation exposure of the new aircraft’s crew, Aviation Week pointed out that recent Soviet publications had mentioned technological breakthroughs in protection. Indeed, the magazine noted that, in recent years, the number of Soviet publications concerning the use of nuclear energy in aircraft construction had increased significantly.

Aviation Week pointed out that a similar increase in the number of publications had preceded the tests of the first Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile and the launch of the very first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, in 1957.

According to the magazine,

Recent speculative stories in the Soviet popular press suggest conditioning the Russian people to an announcement of a spectacular achievement by an atomic-powered aircraft in the near future, probably a nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world.

(Dramatic music)

Aviation Week tightened the screws a little further by adding to its article a short text which quoted Major General Donald John Keirn, Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff of the USAF responsible for nuclear weapons systems and director of the United States Atomic Energy Commission responsible for aircraft nuclear engines.

The first lines of that text read as follows:

Imagine a fleet of ‘enemy’ high-speed aircraft continuously patrolling the airspace just outside our early-warning net, capable of air-launching a devastating missile attack against our hardened installations. Through a consideration of these capabilities, combined with those possessed by the intercontinental-range ballistic missile, the degree of possible future threat of surprise attack immediately becomes apparent…

(Dramatic music)

The 1 December 1958 issue of Aviation Week also contained an editorial by the editor and publisher of that publication.

Robert B. Hotz pulled no punches. The appearance of the new Soviet aircraft came as a crushing shock to everyone involved in America’s nuclear aircraft program. “For, once again, the Soviets have beaten us needlessly to a significant technical punch.”

Worse still, “it is clear to even the most conservative technical analysts that we are at least four years behind the Russians in this critical area,” a lag due to “the technical timidity, penny-pinching, and lack of vision that have characterized our own political leaders.”

Hotz denounced the weasel phrases that spokespersons of the administration led by President Dwight David “Ike” Eisenhower, a gentleman mentioned many times in our scintillating blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since March 2018, would obviously utter to calm things down.

In fact, the existence of the Soviet aircraft was known in American and foreign official circles. Did Keirn not say he would not be surprised to see a Soviet nuclear-powered aircraft fly before the end of 1958?

Hotz denounced the hostility of James Rhyne Killian, Junior, president on leave of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and chairperson of the President’s Science Advisory Committee, towards the American nuclear aircraft program.

He also denounced the hostility of the Secretary of Defense between 1953 and 1957, Charles Erwin “Engine Charlie” Wilson, a gentleman mentioned in September 2018, April 2022 and February 2023 issues of our amazing blog / bulletin / thingee, towards that same program.

And yes, MIT was mentioned several times in our you know what.

Hotz concluded his editorial, dare I say his diatribe, with the following lines:

During the past few years, we have heard much from our political leaders on how much we can or cannot ‘afford’ for the defense of this country.

These were the same years that we have been belabored with vigorous efforts to cut the strength of our military forces in being and jeopardize our military future bv sabre slashes through the research and development budget.

These were the same years the Soviets appeared first with their huge turbojet and turboprop gas turbines, their medium-range ballistic missiles, [intercontinental ballistic missile] and Sputniks.

In view of these Soviet technical achievements, it is more pertinent to ask:

How much longer can we ‘afford’ this kind of leadership and still survive as a free nation?

(Dramatic… Err, sorry.

By the way, the installation of the small nuclear reactor on board the B-36 known as the Nuclear Test Aircraft was carried out within the framework of the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program, a joint military and civilian program which brought together the USAF and the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

Indeed, the ANP had its origins in a military program launched in May 1946. That Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft program became the ANP in May 1951.

And yes, American engineers were also toiling on a direct cycle nuclear engine. In fact, engineers from two American aircraft engine manufacturers were toiling on two types of aircraft nuclear engines, direct and indirect cycle engines.

That second type of engine was much more complex than the direct cycle engine, by the way, which was no small thing considering the great complexity of the latter.

The air entering an indirect cycle engine is compressed by a completely conventional compressor. That compressed air then passes through a heat exchanger in which a cooling liquid coming from the reactor core circulates. In doing so, it heats up considerably. In return, the cooling liquid is cooled by that air before returning to the reactor core, which prevents it from melting. The very hot air which leaves the heat exchanger is channeled towards a turbine which activates the aforementioned compressor. It then leaves the engine through a nozzle, producing considerable thrust.

The subject of this pontification being other than the ANP, I will not bust your chops any further with a history of what was happening in the United States.

You are welcome, and…

Why are you so agitated, my reading friend? You want to know the impact of the article which appeared in the 1 December 1958 issue of Aviation Week? Why did you not say (type?) so sooner?

As you might imagine, the article in question did not go unnoticed. Dozens, nay, hundreds of American daily newspapers talked about it. Many Canadian and foreign daily newspapers also talked about it.

In fact, at least one English daily pointed out that this news considerably tempered the jubilation of the American authorities following the first successful intercontinental flight of the first American intercontinental ballistic missile, the Convair SM-65 Atlas, barely 4 days before the publication of the plethora of articles on the new Soviet aircraft.

In any event, when questioned by journalists on 1 December, yes, yes, on 1 December 1958, about Aviation Week’s bombshell article, the Secretary of Defense, Neil Hosler McElroy, said he was “highly skeptical.” He conceded at most that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) could have a “slight lead” over the United States. Indeed, McElroy saw no need to accelerate the work underway under the aforementioned ANP program.

Western sources based in Moskvá / Moscow, USSR, reported that they had not heard of the nuclear-powered aircraft mentioned by Aviation Week, and no one had seen it, be that in the air or on the ground.

This being said (typed?), several daily newspapers informed their readers that mysterious condensation trails formed by unidentified fast aircraft had been seen in the skies of Moscow.

Indeed, again, at least one news agency pointed out that the aforementioned Keirn had told journalists 10 or so days before the publication of the article that a nuclear-powered aircraft could take to the air in the USSR before the end of 1958, or in early 1959. Assuming that happened, he did not expect that machine to be very sophisticated.

Rightly or wrongly, the news agency concluded that Keirn seemed to believe that the aircraft in question would be a simple flying test bed carrying a small nuclear reactor, in a way a Soviet equivalent of the aforementioned B-36.

That was also the opinion expressed at the beginning of December 1958 by the director of a major English engine manufacturer mentioned in a December 2022 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, de Havilland Engine Company Limited, Alexander D. Baxter, before that the boss of the Nuclear Power Group of that firm.

The Daily Telegraph of London, England, a conservative daily newspaper which certainly could not be suspected of sympathising with the USSR, seemed to show a certain skepticism towards the existence of a Soviet nuclear-powered aircraft. How else could one explain its list of factors which advocated for said skepticism, a list which went beyond the absence of sightings of the mysterious aircraft or the absence of publications on solutions to the problems posed by nuclear propulsion?

According to the daily, the development of the American defence budget being almost complete, a budget which did not allow the realisation of all programs, the publication of texts on Soviet advances in one area or another could influence decision-makers and lead to a reallocation of certain funds.

Furthermore, the Soviet government having not hesitated to announce the progress of its intercontinental ballistic missile program, The Daily Telegraph wondered why said government had not attempted to maximise the propaganda impact of its new aircraft.

Finally, the London daily raised certain objections of a technical nature. Since any nuclear engine mounted on an aircraft was by definition very heavy, for example, the positioning of the Soviet nuclear-powered aircraft’s engines, halfway between the fuselage and the wingtips, was less logical than an installation in its fuselage.

This being said (typed?), many American dailies, including at least two among the most influential, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, both based in New York, New York, almost instantly supported the allegations contained in the article published by Aviation Week.

How will this Cold War tale end, you ask, my reading friend? Another good question. Come back soon, real soon, to read all about it.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)