“Petrol will never kill electricity, especially if the latter is defended by a Kriéger.” Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger and his electric automobiles, including some of the first hybrid vehicles on planet Earth, part 1

Hail, my reading friend, on this day of July 2024. Allow me to welcome you to this issue of our electrifying blog / bulletin / thingee, an issue dedicated to the automotive industry.

Our story began in May 1868, in Paris, France, and not Paris, Texas, with the arrival in this world of Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger. Very imaginative from a young age, that young human apparently put ideas on paper for an electric tram around 1876. I kid you not.

This being said (typed?), yours truly must admit some doubts regarding those ideas. You see, it was only in May 1881 that the first passengers of the first electric tram in the world took their seat aboard said vehicle, the Straßenbahn Groß-Lichterfelde of Berlin, German Empire, mentioned extensively in a July 2021 issue of our encyclopedic blog / bulletin / thingee. Anyway, let us move on.

Graduating from the École centrale des arts et manufactures, one of the great engineering schools of France, in 1891, Kriéger soon became interested in a brand-new invention, the horseless carriage, in other words the automobile.

The young engineer might, I repeat might, have acquired that interest while he seemed to be working for a French manufacturer of rechargeable batteries, the Société anonyme l’accumulateur multitubulaire, a firm which became the Société (anonyme?) l’accumulateur Fulmen around July 1893.

Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger at the wheel of the horse-drawn fiacre of the Compagnie l’Abeille transformed into an electric vehicle under his direction in 1895. Anon., “Note historique sur les véhicules électriques.” Revue industrielle, February 1924, 494.

In May 1895 at the latest, Kriéger tested an old (1884?) horse-drawn fiacre from the Compagnie l’Abeille, purchased around November 1894 then transformed into an electric vehicle / electromobile / accumobile under his direction, and under an eminent patronage, by the staff of the Société de carrosserie industrielle. Said vehicle could travel just over 30 kilometres (about 20 miles) before running out of juice.

To answer the question forming in your little noggin, a fiacre was for all intent and purposes a taxicab.

Cur simplici vocabulo uti si tam bene complicatum verbum facit officium? In other words, why use a simple word if a complicated word does its job so well? Is that not the motto of museum curators around the world? (Hello EG, EP, etc.!) Sorry, sorry. Back to our story.

Kriéger might, I repeat might, have received help from a brilliant Russian engineer of Polish origin, Wacław Kamil Rechniewski, chief engineer of the Société Anonyme des establishments Postel-Vinay.

In any event, Kriéger’s front-wheel drive (!) prototype generated much surprise among Paris fiacre drivers. It behaved relatively well but steering proved difficult and it lacked solidity, something Kriéger readily acknowledged. Indeed, since the body of the vehicle had not been designed to support the weight of the rechargeable batteries, it failed after a year of more or less commercial use.

Kriéger might, I repeat might, have completed a second prototype in 1895, and…

Yes, yes, you read correctly, my reading friend, Kriéger seemed to be one of the first people who put together a front-wheel drive vehicle.

In June 1895, Kriéger was among the people on board the 4 (or 6?) seat electric automobile manufactured under the direction of the co-founder of the Société Gaillardet et Jeantaud, the French businessman / coachbuilder Jean Baptiste Jeantaud, better known as Charles Jeantaud, with the help of his friend Camille Brault, during at least part of the June 1895 Course de voitures automobiles Paris-Bordeaux-Paris, a journey of nearly 1 200 kilometres (nearly 750 miles).

It should be noted that the vehicle in question made the return trip to Paris only towards the end of June, or even the beginning of July. Indeed, it only arrived in Bordeaux, France, 4 days after the start of the race – and approximately 34 hours after the return to Paris of the official winner of the competition, the French industrialist Paul Koechlin.

And yes, my reading friend, the Course de voitures automobiles Paris-Bordeaux-Paris was / is often deemed to be the first automobile race in the world, even though

- it did not / does not correspond to a modern competition where the fastest vehicle was the winner, and

- a race had taken place in Italy in May 1895, the Torino-Asti-Torino.

And I will answer the question you were about to ask. The first car to cross the finish line of the Course de voitures automobiles Paris-Bordeaux-Paris was a 2-seater vehicle driven by the French engineer Émile Constant Levassor.

Yes, yes, that Levassor, the founder, with the French engineer Louis François René Panhard, of the Société anonyme des Anciens Établissements Panhard & Levassor, the first French manufacturer of horseless carriages, but back to our story.

As the regulations for the race required the participation of 4-seater vehicles, the 1st automobile of that type, which happened to be the 4th automobile to have crossed the finish line, was declared the winner. Yes, it was indeed the one driven by Koechlin. As you might well imagine, that decision sparked an outcry, but I digress.

Kriéger and a small team manufactured their first entirely original electric vehicle, with front wheel drive, I think, in 1896. Its structure was metallic in order to properly support the weight of the rechargeable batteries and the 2 electric motors, one per driving wheel.

By the way, Kriéger obtained a patent for a nickel-iron rechargeable battery in December 1896. By way of comparison, it was in July 1901 that a more or less similar patent application from Thomas Alva Edison, a great American inventor mentioned several times in our dazzling blog / bulletin / thingee since July 2019, was received or approved.

And no, Edison did not invent the nickel-iron or nickel-cadmium battery – just as he did not invent the incandescent light bulb, as many Americans seem to believe. Other individuals had invented incandescent light bulbs before him.

And no, Edison Storage Battery Company was apparently not the first manufacturer of nickel-iron or nickel-cadmium rechargeable batteries either. That honour apparently went to a Swedish firm, Ackumulator Aktiebolaget Jungner, founded by the Swedish engineer / inventor Ernst Waldemar Jungner.

Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger. Anon., “Juste récompense.” L’Auto, 10 December 1904, 3.

Kriéger launched his own workshop to manufacture electric automobiles in December 1895. That firm was the Société des voitures électriques, of which we can find traces as early as August 1897 in French publications of the time.

That firm became the Compagnie des automobiles électriques at the very beginning of 1898. The catch with that was that the expression Société des voitures électriques was still used in February 1900. Worse still, the shareholders then voted to dissolve that firm.

There was, however, a cherry on top of that cake. Would you believe that, at the end of June 1898, I think, another French firm, the Société française pour l’industrie et les mines, acquired the firm and patents of Kriéger, creating the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques, whose technical director was… Kriéger, but back to our story and... Yes, in August 1897.

A little before mid-August, Kriéger “presented” to the members of the Automobile-Club de France another electric automobile, much more advanced than the first. Yours truly unfortunately does not know if that vehicle was presented or given to said members.

Incidentally, the Automobile-Club de France was mentioned in August 2019 and February 2024 issues of our ever-interesting blog / bulletin / thingee.

That 4-seater automobile, manufactured by the staff of the aforementioned Société de carrosserie industrielle, might have been the first example of the electric fiacres promised to Parisians for a while, to complement the horse-drawn fiacres, and…

Yes, yes, promised for a while. You see, there were no automobile fiacres in Paris at that time. Worse still, to quote a text, translated here, by journalist Paul Puy published in a Parisian daily, Le journal des sports, around August 1897, “So, London currently has 150 electric fiacres, intended for public service, and London is far behind Paris on the automobile field. What would it be like if we were not ahead?”

A brief digression if I may. The very first Bersey electric fiacres of the English firm London Electrical Cab Company Limited went into service in… August 1897. Hardly more than a handful rolled in London during that month, or in September. Indeed, the total number of fiacres produced in 1897-98, or 1897-99 I cannot state, by Great Horseless Carriage Company Limited and Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Company Limited barely exceeded 75. We are far from the 150 mentioned by Puy, and…

You have a question, do you not, my reading friend? I will answer it by saying (typing?) that Walter Charles Bersey was an English electrical engineer who, at that time, was the managing director of London Electrical Cab, a firm which closed its doors around August 1899, but back to our story.

And yes, Great Horseless Carriage was indeed mentioned in a March 2024 issue of our amaaazing blog / bulletin / thingee.

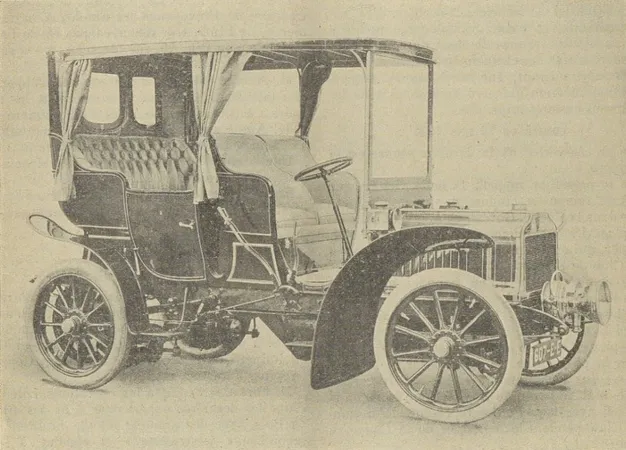

A coupe-type electric fiacre presented by the Compagnie des Automobiles Électriques at the Concours de voitures de place automobiles organised in June 1898 by the Automobile-Club de France. Anon., “Fiacre électrique Kriéger.” La Locomotion automobile, 31 March 1898, 193.

Kriéger was one of the dozen manufacturers who took part in the Concours de voitures de place automobiles launched by the Automobile-Club de France around August 1897. In fact, he presented 4 different front-wheel drive vehicles during that competition which took place in Paris in June 1898 over a period of 12 days. Three of them were of the type that Kriéger wished to series produce. Mechanically identical, they differed only in their easily interchangeable bodyworks and sold for 12 000 francs, an amount which corresponded to $79 000 or so in 2024 currency.

Incidentally, a voiture de place was for all intent and purposes a fiacre, in other words a taxicab.

All in all, 7 manufacturers entered 19 electric fiacres in the competition. Five others registered 9 petrol fiacres.

In reality, however, barely 12 vehicles took part in the competition, including only one petrol fiacre. The almost total absence of petrol fiacres was seemingly due to the fact that their manufacturers had the impression that electric fiacres would receive preferential treatment.

Mind you, a manufacturer of electric fiacres, the Compagnie française des voitures électromobiles, did not participate in the competition because the French engineer Jules Maurice Bixio was part of the jury. You see, he was chairman of the board of directors of the Compagnie générale des voitures, an important Parisian fiacre operator closely associated with the Compagnie française des voitures électromobiles.

Even though the hyper-detailed report approved by the jury in October 1898 did not mention a great winner as such, the fact was that the 3 pre-production vehicles of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques performed very well. Two of them were at the top of their category while the third, out of competition given its characteristics, also impressed a lot. All three also consumed less electricity than vehicles from rival firms.

Kriéger seemingly received a prize of 1 000 francs, or about $6 600 in 2024 currency.

The successes achieved by Kriéger soon impressed many industrialists. In 1898, the German firm Kölner Electricitäts-Actiengesellschaft vor dem Louis Welter & Compagnie imported one of his vehicles. It then contacted a German rechargeable battery manufacturer, Kölner Accumulatoren-Werke (KAW), to see if it could design something interesting.

The new rechargeable battery was so impressive that Kölner Electricitäts-Actiengesellschaft vor dem Louis Welter & Compagnie and KAW joined forces in 1900 to create Allgemeine Betriebs-Gesellschaft für Motorfahrzeuge (ABAM). Having acquired production rights for the technology developed by Kriéger, ABAM began production of Urbanus (trucks and omnibuses) and KAW (private automobiles and fiacres) electric vehicles.

Between 1900 and 1908, ABAM might, I repeat might, have produced 1 500 or so electric vehicles.

Interestingly, the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques joined forces with ABAM in 1905 to create Krieger Automobil Actiengesellschaft, a firm which put up a garage with charging stations in Berlin, German Empire.

Ten or so Kriéger electric fiacres might, I repeat might, have circulated in Paris from the beginning of 1899 onward. Yours truly unfortunately does not know who those somewhat expensive vehicles belonged to. Indeed, did you know that one of them apparently cost a trifling 50 000 francs, or around $330 000 in 2024 currency? Wah!

Interestingly, a Kriéger electric fiacre circulated in the streets of London in January 1899, apparently for the purpose of an experiment, a performance organised by an English firm, Motor Car Company. It aroused a certain enthusiasm among experts, without winning the slightest order, however.

An interesting episode in the saga of Kriéger’s electric vehicles began in another anglophone country, the United States, in the spring of 1899.

Believing they were seeing a growing interest in motorised fiacres in New York, New York, a group of American businessmen founded General Carriage Company in May, and obtained what appeared to be an exclusive license for all road transport for the entire state of New York (!), to the great displeasure of a powerful firm founded in September 1897, Electric Vehicle Company.

Aware that this rival was not going to allow it to use its own supplier of electric fiacres, General Carriage bought the manufacturing rights to the Hoadley-Knight compressed air engine.

If I may be allowed to express an opinion, that descriptor was actually a misnomer. Joseph H. Hoadley was an American financier who could not have designed a spoon had his life depended on it. The brain behind the Hoadley-Knight engine was in fact Walter H. Knight, an engineer employed by General Electric Company, an American giant mentioned in several / many issues of our exceptional blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since April 2018.

And yes, it was an American firm headed by Hoadley, International Air Power Company, which was to produce the fiacres intended for General Carriage.

International Air Power and another firm in which Hoadley was involved, New York Autotruck Company, found themselves in hot air, err, water at that time, however. The second was actually committed to producing compressed air trucks which would crisscross the streets, boulevards and avenues of the Big Apple in large numbers.

With no trucks assembled or built, International Air Power, New York Autotruck and Hoadley were heavily criticised during the summer of 1899, which explained why International Air Power had become International Power Company even before the end of the spring of that year.

With the compressed air motor proving to be little more than hot air, sorry, sorry, at least in the case of automobiles, General Carriage turned its sights toward the electric motor. Indeed, the American firm might well have thought of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques before abandoning the Hoadley-Knight engine once and for all, and…

You have a question, my reading friend? Very well. What did I mean by the expression at least in the case of automobiles? A good question. You see, Hoadley-Knight engines powered a number of streetcars in New York and Chicago, Illinois, before and after 1900. This being said (typed?), those cars deemed smoky, smelly and dusty by more than a few users in no way undermined the domination of electric traction.

In any event, General Carriage received 1 or 2 Kriéger electric fiacres even before the end of May 1899. It might also have purchased the production rights for those vehicles. Indeed, its management might, I repeat might, have considered the possibility of ordering up to 1 000 (!) electric fiacres which would be produced on American soil.

Even though General Carriage seemed to receive a certain number of (electric?) (Kriéger??) fiacres around April 1900, the fact was that it did not manage to carve out a place for itself in the New York fiacre market. It became Manhattan Transit Company around May 1902. Kriéger electric fiacres no longer interested it at all, but back to our engineer.

Kriéger was obviously one of the 6 manufacturers who took part in the 2nd Concoures des fiacres, held in Paris at the beginning of June 1899, over a period of 11 days. He entered one of the 10 participating vehicles, all of them electric with the exception of 2 petrol vehicles. Even though the report of the results, made public in August, did not mention a winner as such, the fact was that the fiacre of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques once again performed very well.

A typical delivery van of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques. Anon., “Heavy Motor-Car Trials in France.” The Engineer, 28 October 1898, 424.

It should be noted that the staff of the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques manufactured several electric delivery vans in 1899, some of which were used by the large Parisian department store Au Bon Marché.

It was also in 1899 that the Compagnie parisienne des voitures électriques sold certain production rights to the Société française d’automobiles électriques. Do not forget that name, my reading friend. We will get back to it.

The prototype of the Kriéger Électrolette electric automobile. Louis Antoine Jules Tony Kriéger was at the wheel, on the left of the photograph. Georges Prade, “Une nouvelle voiture électrique.” La Vie au Grand Air, 10 December 1899, 152.

Mind you, Kriéger also gave himself a little gift at the end of 1899, by designing the Électrolette, a small 2-seater automobile capable, it was said, of approaching 80 kilometres/hour (50 or so miles/hour) on a good, straight road.

Do you have doubts about that velocity, my skeptical reading friend? Me too, but we might both be wrong. Some of those early automobiles could move surprisingly fast, which could prove lethal to the people onboard, and those who happened to be in the way. Anyway, let us move on.

A French sports journalist and editor of the Parisian sports daily L’Auto-Vélo, Georges Prade, raised an interesting point about that vehicle, a point which was still very valid 125 years later, in the article he published in a December 1899 issue of the Parisian sports weekly La Vie au Grand Air, words translated here: “The absence of chain and any metal gear gives a silent ride, too silent even, because one arrives at 60 per hour on a car or on a passerby without any sound warning him, or her.”

Yes, my reading friend, this 60 per hour obviously corresponded to 60 kilometres/hour (38 or so miles/hour).

Indeed, Kriéger was traveling at a rather high speed, at the end of November 1899, in the evening, in Paris, when he hit a horse-drawn fiacre, throwing the sleeping coachman, Louis Tony, and his horse to the ground. While the fiacre was traveling in the left lane, the wrong lane, Kriéger did not blow his horn before making the turn at an intersection which caused the collision. The engineer was ordered to pay a fine of 100 francs, and to remit the sum of 1 000 francs to Tony, sums which corresponded respectively to approximately $660 and $6 600 in 2024 currency.

Would you believe that Kriéger was involved in at least one other accident? I kid you not. In May 1903, in Paris, he hit an electric fiacre driven by the wattman Henri Seraye. That latter vehicle in turn hit a ladder on which a billsticker of the Grands Magasins Dufayel, one of the large Parisian department stores of the time, was working. Thrown to the ground, Jules Grison suffered multiple bruises and had to be hospitalised. Émile Simon, who was holding the ladder, was tightly squeezed between the fiacre and a palisade and also suffered multiple bruises, but I digress.

Aware of the need to promote his vehicles, Kriéger took part in the Critérium des voitures électriques of the Parisian sports daily Le Vélo, held at the end of April 1900. Indeed, he won that competition by covering a distance of 152 or so kilometres (94 or so miles), between Paris and Laroche, France, perhaps a world record, and this without having to use the charging stations placed along the road. It should be noted, however, that only 3 manufacturers had dared to embark on that adventure.

And yes, my reading friend, a 3rd fiacre competition was held in Paris in August 1900, over a period of 6 days. Kriéger was still in the running, this time with 2 vehicles out of a total of 14 registrations, including 5 petrol fiacres. Said vehicles won the gold medal in the electric voitures de place / fiacres category. Mind you, Kriéger also returned home with the gold medal in the electric delivery van category.

At that time, however, the electric fiacre was no longer really popular with the public. A ride was often very expensive. You see, many drivers were seemingly ordered not to drive more than 35 to 40 kilometres (22 to 25 miles) in one go. Parisian passengers wishing to travel far from downtown therefore had to put up with spending at least 2 hours (!) at a charging station. I kid you not.

Let us also mention that charging stations were not common in France in 1900. Apparently few in number in Paris, they seemed virtually non-existent in the regions.

To quote a sentence, translated here, extracted from a text by French sports journalist Paul Meyan published in August 1900 in a renowned Parisian daily, Le Figaro, “Ah! certainly, electricity is the future, we are convinced of it; but it is still only a future.”

Practically 125 years later, have things really changed? To paraphrase a world-famous beagle named Snoopy, curse you, petroleum! Sorry, sorry. Let us talk (type?) about something else. In fact, why not end the 1st part of this article right now?

See you later.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)