If at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try, try, try again: The odd story of the Piaggio P-7

It is with a certain trepidation that yours truly approaches the subject of this week, my reading friend. I feel a certain discomfort at the idea of talking about an aircraft designed in Italy during the years during which the Partito Nazionale Fascista, an unsavoury organisation led by Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini, a pompous brute and buffoonish dictator mentioned in August 2018, December 2018 and July 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, held the reins of power.

This being said (typed?), I dare to hope that it is possible to examine the story of the Piaggio P-7 despite the monstrosity of the political regime which oversaw its birth. I dare to hope that you share this point of view.

Let us begin at the beginning. Yours truly found the photograph at the heart of this article in the December 1929 issue of a very interesting Spanish monthly magazine, Aérea, preserved in the fabulous library of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario.

Have you ever heard of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider? No? That’s not important. Said cup was awarded to the winner of a seaplane race created by Jacques Schneider, a wealthy French industrialist fascinated by aviation, whose first edition was held in April 1913. Interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, in 1914, this international competition really took off from 1920 on, thus becoming the most prestigious air race in Europe. Countries such as France, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States saw it as an excellent opportunity to demonstrate the superiority of their aeronautical technology. The successes of the Italian and British teams were such that they soon became the only ones left in the running.

By the way, the British team won the race for the third time in a row in September 1931, which earned the United Kingdom the great honour of keeping the magnificent Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider in perpetuity.

Would you believe that the British government, grappling with a serious economic crisis, the Great Depression was beginning let’s not forget, had refused to finance the design and construction of a racing seaplane for said race? Many British aviation enthusiasts were outraged by this decision. Lady Lucy Houston, born Fanny Lucy “Poppy” Radnall, was so outraged that she handed over the necessary funds to Supermarine Aviation Works Limited, a division of Vickers (Aviation) Limited, itself a subsidiary of the British military industrial giant Vickers-Armstrongs Limited.

What was / is not always said was / is that this fairy godmother of the Royal Air Force, as she was sometimes called, the most fervent supporter of British aviation during the interwar period, and also the most generous donor, was a great admirer of the aforementioned Mussolini, the most magnificent statesman of the modern era according to her. Having said (typed?) this, let us leave this sulphurous person to return to our story. And then no, let us keep a distance from our story for another moment. Would not it be fascinating to tackle in a temporary (travelling?) exhibition the links between aviation and Fascism, National Socialism and Marxist Leninist Stalinism during the interwar years? But I digress. Sorry.

In 1929, the Fascist government led by Mussolini intended to win the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider which was to be held in the United Kingdom in September of that year. You see, none of the 3 racing seaplanes of the Italian team had completed the course of the 1927 edition of the race. This humiliation was all the more serious in that said race had taken place in Venice, Italy, in front of a huge crowd. The Italian air minister, Italo Balbo, a brute with the looks of a movie star mentioned in an August 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, was furious. He soon created a special unit, the Reparto Alta Velocita, within the Italian air force, the Regia Aeronautica. Four aircraft manufacturers began before long to design high performance racing seaplanes. The best of them would defend the honour of Fascist Italy in 1929.

One of the engineers who designed an aircraft for this 1929 edition of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider had been working for Società Anónima Piaggio & Compagnia since 1923. His name was Giovanni Pegna. And yes, this truck and railway vehicle manufacturer which had launched into aeronautics during the First World War was mentioned in an August 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Born in January 1888, Pegna was a brilliant and original designer fascinated by aviation since the mid-1900s who did not hesitate to push the limits of the possible in terms of aeronautical technology.

Like many aeronautical engineers in the 1920s, Pegna believed that competitions such as the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider were a great way to advance aeronautical technology. In fact, he fervently believed that seaplanes, not landplanes, were the best way to reach higher and higher speeds, and this for 2 reasons:

- the more or less infinite length of available bodies of water allowed them to make the most of the power of their engine, regardless of their weight, and

- the presence of a landing gear on landplanes, a source of drag / air resistance, which had to be faired or retracted, which could be problematic in the case of small airplanes.

Recognising that the floats of floatplanes and the hull, hydrodynamic but not very aerodynamic, of flying boats accounted for much of the air resistance that these aircraft had to overcome in order to go faster and faster, Pegna designed, over the course of the 1920s, 5 less and less conventional seaplanes mainly intended for racing. Only a biplane floatplane fighter went beyond the drawing board stage. It was not even completed actually.

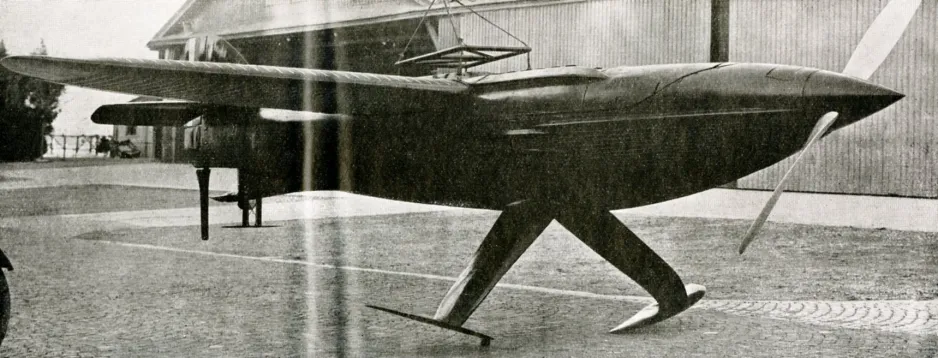

The Piaggio P-7 out of its element. The main lifting surfaces, or foils, are clearly visible, as is the small lifting surface under the tail. Pierre Léglise, “Solutions italiennes au problème des grandes vitesses.” L’Aéronautique, April 1940, 136.

Pegna’s quest for aerodynamic finesse resulted in the outright elimination of the floats and hull of conventional seaplanes. The engineer replaced them with 2 main lifting surfaces, or foils, supported by 2 streamlined legs attached to a fuselage / hull which was highly aerodynamic and fully watertight – for obvious reasons. The wings were also equally watertight.

The engine of the aircraft, placed just in front of the wings, operated a small marine propeller placed under the tail. This made movement on the water possible and allowed the aircraft to accelerate until the main lifting surfaces and the small lifting surface under the tail were able to lift its nose out of the water. The pilot only had to disengage the marine propeller and engage the large aerial propeller of the aircraft, placed in its nose. Its speed augmenting very rapidly, the aircraft soon took off. Said aircraft obviously was the Piaggio P-7 whose photograph you saw at the beginning of this article.

As was / is often the case in the wonderful world of aeronautical / aerospace technology, the concept of Pegna was not really new. Let’s go back in time, my reading friend, to find out more.

That story began in the United Kingdom in 1911. Like many other young women and men of his time, a young Royal Navy officer, Charles Dennistoun Burney, discovered a passion for wings. He was particularly interested in the use of aircraft far from shore.

Familiar, just like the aforementioned Pegna actually, with the work of an Italian engineer and inventor mentioned in November 2018 and July 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, Enrico Forlanini, who had completed and tested a hydrofoil in 1906, Burney began to cogitate, and ... What is a hydrofoil, you ask my reading friend who does not seem to have read the December 2018 issue of this same blog / bulletin / thingee in which yours truly explained what this was all about?

Wishing to make up for your lack of knowledge, I will quote myself.

Water, as you undoubtedly know, is a great deal denser than air. A wing like surface travelling through water will therefore produce a great deal more lift than a similar surface travelling through air. Now imagine a boat or ship fitted with specially designed lifting surfaces, or foils. When moving at low speed, this boat or ship would look perfectly ordinary. As it reached a critical speed, however, the lift produced by the foils of this boat or ship would raise its hull out of the water, greatly reducing water resistance and allowing it to travel at high speed.

Wishing to provide the Royal Navy with aircraft that could be used on the high seas, to improve the accuracy of the artillery salvos fired by battleships for example, Burney discretely / secretly contacted the management of British & Colonial Airplane Company. Intrigued by his ideas and informed that the Royal Navy supported them, the aircraft manufacturer agreed to create a secret design office, Department X, to develop the Bristol-Burney X seaplane, and this even before the end of 1911.

A prototype, equipped with 2 marine and 1 aerial propellers, and ladder-like lifting surfaces, began its tests, in the greatest secrecy, in May 1912. A first test of this 2-seat monoplane having failed to provide good results, the X was subsequently towed by a small warship. It took off in September but crashed almost immediately. The pilot was not injured.

An improved and larger second prototype was made around March 1913. Devoid of wings and equipped with a weak engine for testing purposes only, this X was also towed by a small warship. Equipped later on with its wings and a much more powerful engine, it began its flight tests in June 1914. The X ran aground on an underwater sandbar before taking to the air, however.

Faced with the possibility of a European war, the Royal Navy abandoned the project in July, a few days after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria-Este, of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It should be noted that Burney took advantage of his experience with the Xs to develop, in 1915, a very effective anti-mine device towed by a ship, the paravane. A version of this small underwater glider fitted with an explosive charge was later used against submarines.

Fascinated as I am by these flying cetaceans that are airships, yours truly must emphasise that Burney thereafter discovered a passion for this means of transport in the early 1920s. The British government wishing to examine the possibility of using rigid airships to create a transport network between the United Kingdom and the Dominions, including Canada, Vickers Limited, as this firm was called before it became Vickers-Armstrong, founded Airship Guarantee Company Limited. This subsidiary headed by Burney designed 1 of the 2 airships of the imperial airship transport program, the R-100.

And yes, you are right, my reading friend, it was under this program that the federal government financed the construction of an airport at Saint-Hubert, Québec – the first Canadian civilian airport financed by this level of government. Like everyone on our good old Earth, you are not unaware that the R-100 spent about 2 weeks in Canada in August 1930. And yes, this giant airship was mentioned in a July 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

What you may not know is that, according to some people, a British streamlined car whose design was supervised by Burney may, something I strongly doubt I must say (type?), have played a crucial role in history of the automobile. Indeed, in 1934, the monstrous leader of National Socialist Germany, Adolf Hitler, may, I repeat, may have given to brilliant automotive designer Ferdinand Anton Porsche some sketches derived from the Streamline / Crossley Streamline, nicknamed the R-100 car, an innovative vehicle manufactured in very, very small numbers between 1929 and 1933 by Streamline Cars Limited and Crossley Motors Limited. And yes, Porsche was mentioned in August 2017 and March 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Whether this detail was / is true or not, the fact was / is that Hitler wanted to launch the production of an economic automobile that millions of German families, the ones with the proper bloodline, could afford. The first prototypes of the Kraft durch Freude Wagen, or KdF Wagen, left the factory in 1938.

KdF, in other words strength through joy, was a huge and very popular agency created in late 1933 by the National Socialist government to keep the average working class German, the ones with the proper bloodline, quiet and happy as more and more resources that could be used to make her / his life better went into the acquisition of ever greater numbers of ever more expensive killing machines.

KdF achieved its objective through paid vacations, cheap movie / theatre tickets, low cost cruises, brief excursions to cultural events, etc., all of which came with heavy doses of propaganda. Mind you, KdF also wanted to improve the working environment in factories, both to improve productivity and to deepen the workers’ attachment to their nation, their “race” and the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeitpartei. Understandably enough, said workers were more interested in KdF’s leisure / tourism activities than in the new cafeteria of their factory, or the propaganda. Mind you, middle class Germans lost no time in taking advantage of the cheap activities as well. Bread and circus, my reading friend. Bread and circus. We would not fall for such nonsense nowadays, now would we? But I digress.

And yes, KdF was inspired by a huge and very popular leisure and tourism agency created by the Fascist government of Italy, the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro.

What is it, my reading friend? You wonder why you should worry about a German automobile that no one has ever heard of? Well, the (sad?) truth was / is that you have heard of this German automobile. Even though the KdF Wagen was not delivered to millions of German customers in the 1930s and 1940s, the world received more than 21.5 million of them between 1946 and 2003. You and I know this vehicle as, yes, you guessed it, the Volkswagen, an automobile mentioned in a June 2019 issue of our you know what.

Did you know that the Volkswagen was strongly inspired by the Standard Superior, an economical German automobile designed by Josef Ganz and launched in 1933? This engineer had to flee National Socialist Germany in 1934, however, because of its virulent anti-Semitism. Ganz’s contribution in the history of the Volkswagen was for a long time virtually stripped from history books, but back to our story.

The seaplane that Pegna designed was the most advanced and the most radical of its time. Dare I say that it was / is also the most unusual / strange of all time? By the way, this aircraft with a wonderful aerodynamic, a beautiful architecture and remarkable aesthetics was nicknamed Pinocchio, for obvious reasons, and…

What is it, my reading friend? Don’t tell me that you do not understand this hint as obvious as the nasal appendage on your pretty face? Sigh. I see. Pinocchio was / is a living wooden puppet, not always very nice, imagined in 1881 by the Italian journalist and author Carlo Collodi, born Carlo Lorenzini, whose nose got longer each time it / he told a lie.

Would you believe that the management of an Italian automobile giant then heavily involved in aeronautical production was so intrigued by the P-7 that it agreed to provide the powerful engine it needed? This firm and / or Piaggio & Compagnia started the design of the transmission and clutch system essential to the success of this ultra-secret project. What was this firm, you ask, my reading friend whose curiosity only exceeds her / his good taste? Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino Società Anónima (FIAT), of course. And yes, this firm was truly mentioned in March, March and September 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The management of FIAT unfortunately decided to withdraw from the project as the design of the P-7 continued. The management of Piaggio & Compagnia therefore had to contact its counterpart at Fabbrica Automobili Isotta-Fraschini Società Anomima. The latter agreed to provide an engine. Fabbrica Automobili Isotta-Fraschini and / or Piaggio & Compagnia started the design of a brand new transmission and clutch system, which was very annoying and delayed the development of the P-7.

This engine change was just one of the many challenges that Pegna and Piaggio & Compagnia had to overcome. As you may imagine, the P-7 was an aircraft of great complexity. Its many innovations required extensive experimentation that could be done at the drop of a hat. The catch, or the fly in the ointment if you prefer, was that Pegna and his team had to complete the development of the P-7 before the closing of the registration period of the 1929 edition of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider. And no, my reading friend, I have not yet found the date of this closing.

Once the aircraft was completed, in late 1928 or early 1929, Piaggio & Compagnia found itself in a somewhat paradoxical, but all in all predictable situation. The P-7 was so radical that some pilots refused to fly it. The company finally managed to find a rare pearl, however. This pilot soon began tests on the water, on a lake in northern Italy. He soon realised that many innovations of the P-7, mainly those relating to its propulsion (exhaust, air intakes, marine propeller, cooling system, transmission and clutch system, etc.), were not functioning properly. The lifting surfaces themselves were also a source of problems.

The various problems were so serious that, despite all his efforts, the pilot of the P-7 apparently did not dare to try to start its aerial propeller, which meant that no attempt at takeoff took place, and… You have a question, my reading friend? Could the pilot really see where he was going when he was on the water, you are wondering? Not really. The forward visibility offered by the cockpit of the P-7 was, how to say it, execrable. And yes, visibility in flight would have just as execrable.

As you may well imagine, the P-7 was far from ready when the registration period of the 1929 edition of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider ended. Three seaplanes produced by another aircraft manufacturer would eventually wear the colours of Fascist Italy.

Rather disappointed by the setbacks of the P-7, Piaggio & Compagnia gave up making a second prototype. Pegna, meanwhile, hoped to resume work on seaplanes with lifting surfaces at a later date. His hopes proved futile. The P-7 was scrapped at an undetermined date.

The publication of 2 photographs of the P-7 at rest in its element in the September 1929 issue of a prestigious Italian monthly, L’Ala d’Italia, proved shocking to all aviation enthusiasts who were not in the know. How did this seaplane take off, wondered the editorial office of a well-known French weekly, Les Ailes, in its 10 October issue? It was so intrigued by the P-7 that it asked said question to its readers.

The editorial office of Les Ailes was amazed by the number of responses, almost 200, received over the next 6 days. While some readers of the magazine believe that the P-7 was towed or catapulted to ensure its takeoff, more than a hundred mentioned the presence of a marine propeller invisible on the photograph. A reader, Fernand Laborde, an engineer working in a field other than aeronautics, even mentioned the presence of lifting surfaces, also invisible on the photograph.

In its explanation of how the P-7 took off, Les Ailes mentioned the marine and aerial propellers, but not the lifting surfaces. The magazine seemed to think that testing was to begin soon.

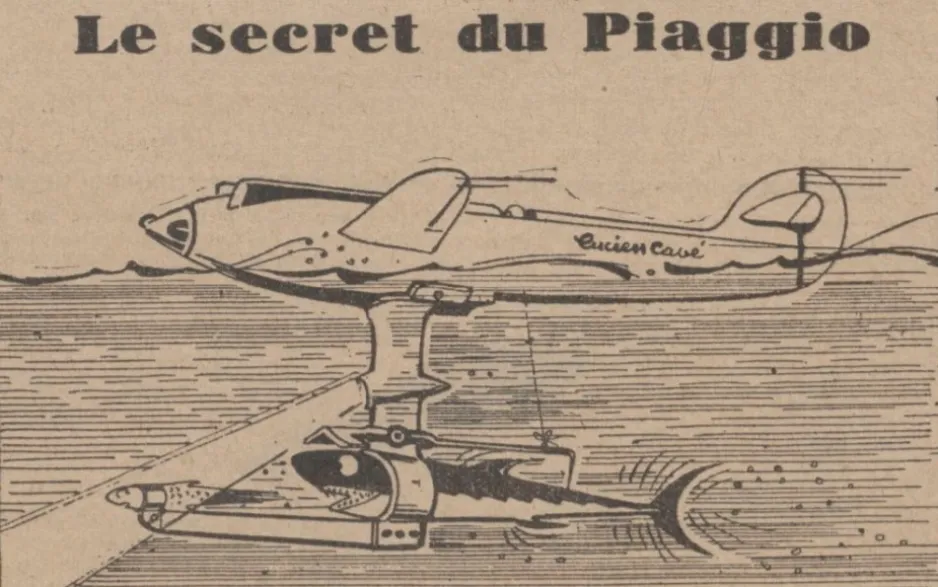

On 24 October, the editorial office of Les Ailes allowed itself the luxury of publishing a drawing by Lucien Cavé, the most famous aviation artist of his time, and the official artist of the Ministère de l’Air and the Aéro-Club de France.

The secret of the Piaggio P-7, according to Lucien Cavé. Lucien Cavé, “Le secret du Piaggio.” Les Ailes, 24 October 1929, 7.

The legend of said drawing read / reads as follows:

To take off, the pilot releases a cable attached under his seat, causing simultaneously: 1° the lowering of the accelerator sting; 2° the raising of the blind system; 3° the shimmering of the bait. A locking system releases the seaplane as soon as its elevation is sufficient to allow the propeller to start.

As intrigued by the P-7 as everyone, the management of the British weekly Flight, an aeronautical magazine famous among all, published Cavé’s drawing in its 1 November 1929 issue.

I must confess I find this drawing both amusing and disturbing. What say ye?

If I may be permitted a digression of extreme brevity, in 1929, the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider was won by a British pilot. The speed reached being nearly 529 kilometres/hour (nearly 329 miles/hour), said pilot could count himself lucky that the P-7 did not participate in the race. Indeed, Pegna thought that his aquatic thoroughbred could reach between 580 and 600 kilometres/hour (about 360 to 375 miles/hour), if not more.

Ironically, the seaplane chosen to defend the honour of Fascist Italy was not functioning properly at the time of the race. Neither of the 2 aircraft registered completed the course. A seaplane used during the 1926 edition of the Coupe d’aviation maritime Jacques Schneider saved the nation’s honour with a second place. The aforementioned Balbo was probably not amused by this result. And you know what, frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn, if I may quote Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind, a classic American film with a shocking racism released in theatres in December 1939, both of them mentioned in an October 2019 issue of this blog / bulletin / thingee!

Pegna died in May 1961 after a long and distinguished career.

Is that all for today, you ask, my reading friend? Not quite.

Indeed, before leaving you, allow me tell you that the rather radical nature of the P-7 inspired a French specialist in remotely controlled scale models. Made between June and September 1987 by Alain Vassel, a model of the P-7 flew in October, in Italy. Improved during the following weeks and months, it flew again, in France, in August 1988, and in Italy, in October. Two Italian modellers completed another model which flew no later than 2015.

These remotely controlled scale models validated the concept of Pegna. And yes, these successes followed in the wake of initial trials full of problems. If I may paraphrase Jonathan J. “Jack” O’Neill, one of the main characters in the Canadian American / American Canadian military science fiction television series Stargate SG-1 broadcasted between 1997 and 2007, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try, try, try again.

Ciao, and goodbye.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)