Wings over the world: The PT6 turboprop and turboshaft engine, Part 1

Allow me to offer you a big safe aerospace salute, my reading friend. I would like to talk (type?) to you about an engine, and what an engine!

In 1956, realising very well that the heyday of the piston engine had passed, the American parent company of Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company Limited of Longueuil, Québec, the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Division of the American aeronautical giant United Aircraft Corporation, gave it a mandate to develop jet engines of limited power.

Shortly thereafter, Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft president Ronald T. Riley asked Richard “Dick” Guthrie, Director of Engineering, to hire a number of engineers who were knowledgeable in jet engines / gas turbines. He wanted to start designing an engine of this type as soon as possible. In fact, Riley wanted to use it to initiate an expansion of Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft which would make it the main engine manufacturer in Canada.

Would you believe me if I told you that Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and United Aircraft were mentioned a few times in our fabulous blog / bulletin / thingee since August 2017? Better yet, Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft was in August 2017 and March 2018 issues. Our world is seriously interconnected, but I digress.

Guthrie was quick to hire 12 engineers from various Canadian and foreign organisations and firms, including the National Research Council (NRC) in Ottawa, Ontario, and Orenda Engines Limited, a subsidiary / division of A.V. Roe Canada Limited of Malton, Ontario, a subsidiary of British aeronautical giant Hawker Siddeley Group Limited. The first members of this design team, Canadians and British, arrived in Longueuil in January 1957.

As usual, it is with pleasure that I remind you that Orenda Engines was mentioned in July 2018, March 2020 and October 2020 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Hawker Siddeley Group, on the other hand, was mentioned many times therein since March 2018.

I also believe I forgot in the past to mention how frequently the NRC was mentioned in our you know what. If I may quote Mork, one of the main characters of the American soap opera Mork & Mindy, which aired between September 1978 and May 1982, shazbot! Sorry.

Even before the end of 1957, the design team from Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and 5 teams from Pratt & Whitney Aircraft prepared sketches for limited power turbojets. The Canadian concept, then known as DS-3J, won.

The management of Pratt & Whitney Aircraft approved the development of the turbojet, redesignated DS-4J, around September 1957. Its Québec subsidiary soon realised, however, that the price to pay to design a high-performance turbojet greatly exceeded its resources. Worse still, Canada’s main funding agency in matters of defence, the Department of Defence Production, was unwilling to get involved in the project. Also interested in the DS-4J, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft took control of the project in January 1958. The Canadian engine then became the Pratt & Whitney JT12. A prototype ran on a test bench in May of that same year.

The JT12 and its military version, the J60, were produced in nearly 2 270 examples. They were used almost exclusively on civilian business aircraft and military light transport aircraft such as the Lockheed JetStar / C-140 Jetstar. Pratt & Whitney Aircraft also manufactured approximately 350 turboshaft engines, a type of gas turbine designed for use in helicopters. These versions of the JT12 even gave rise to industrial and marine versions which, however, do not seem to have been produced in large quantities. But now back to our subject.

And yes, there is a civilian Jetstar in the incredible collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa.

At least one study carried out in 1958 by the Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft design team led it to consider an engine that could be used as a turboprop or turboshaft.

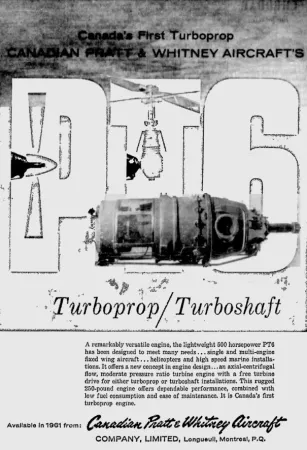

The prototype of the PT6, an engine originally known as the DS-10, ran on a test bench in February 1960. An improved engine took to the air in May 1961 aboard a small twin-engine aircraft from the Royal Canadian Air Force modified for this purpose by de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited of Downsview, Ontario, near Toronto – a well-known aircraft manufacturer mentioned many times in our you know what since March 2018. Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft supplied at least one another engine to an American aircraft manufacturer which mounted it on a prototype helicopter which flew in July 1961. This Hiller 1099 or Ten99 was not produced in series. Impressed by the potential of the new engine, which was much lighter and smaller in size than a piston engine of the same horsepower, the federal government supported it financially.

While the PT6 entered service around the beginning of 1964, the fact was that its development had not gone smoothly. The team which had designed it had virtually no experience in this field. A team of specialists from Pratt & Whitney Aircraft therefore had to spend a few months in Longueuil in order to properly develop the PT6.

It should be noted in passing that Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft became United Aircraft of Canada Limited (UACL) in December 1962.

While the PT6 enjoyed its first success as a business aircraft engine, it soon caught the interest of small-size commuter aircraft manufacturers, including de Havilland Aircraft of Canada. The DHC-6 Twin Otter was indeed very successful for this type of job. The PT6 also proved very popular with many foreign aircraft manufacturers which produced trainers or light transport aircraft for armed forces around the world.

As you know, the Twin Otter prototype is among the aircraft in the aforementioned collection of the aforementioned Canada Aviation and Space Museum. This same collection obviously includes a PT6.

A major West German aircraft engine manufacturer acquired a license to manufacture the PT6 and its marine / industrial version, the ST6, mentioned below, in late 1968. The hopes entertained by MAN Turbo Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung to deliver engines to local aircraft manufacturers proved in vain.

Still in 1968, UACL and a Czech state engine manufacturer, probably Motorlet Národní Podnik, negotiated the sale of a production license for the PT6. The Czech state-owned aircraft manufacturer Let Národní Podnik had chosen the Canadian turboprop to equip a new small-size commuter airliner. In the end, only the initial version of the L-410 Turbolet made use of the PT6, and the production project in Czechoslovakia got nowhere.

UACL was seriously considering converting the PT6 into a turboshaft in the early 1960s. However, helicopter manufacturers did not show much interest. Anxious to power rather large helicopters, engineers at UACL had the idea, in 1965, of coupling a pair of PT6 by means of a system of gears. Bell Helicopter Company, a subsidiary of Bell Aerospace Corporation, itself a subsidiary of American giant Textron Incorporated, thought the idea was excellent. The two firms embarked on the project in November 1967. In 1968, intrigued by the potential of the new engine, the United States Navy signed a development contract through the Canadian Commercial Corporation, the export sales organisation of the Canadian federal government. A prototype of the PT6T Twin Pac ran on a test bench in June 1968. A first test flight was held in May 1969. The civilian Twin Pac and its military version, the T400, were very successful, and this in civilian and military terms.

As you can imagine, Bell Helicopter and Bell Aerospace were mentioned in our blog / bulletin / thingee, in April 2019 on the one hand and in March 2018 and April 2019 on the other hand. Textron was mentioned on several / many occasions since October 2017, but back to our engine.

The wish expressed by the United States Navy to order Bell UH-1 Iroquois equipped with a T400, circa 1969-70, did not go unnoticed, however. Indeed, the chairman of the United States House Committee on Armed Services opposed this. Lucius Mendel Rivers pointed out that the federal government refused to support the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War and did not oppose the entry into Canada of many deserters. Although totally controlled by an American firm, UACL was forced to create a subsidiary in the United States in 1971. Legal considerations led Pratt & Whitney Aircraft of West Virginia Incorporated to become a division of United Aircraft. The new firm assembled the T400s intended for the American armed forces. Renamed Pratt & Whitney Engine Services Incorporated around 1981, this firm specialised in the maintenance and repair of aircraft engines. It still existed as of 2020.

And yes, the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Bell CH-135 Iroquois, a Canadian version of the UH-1. If I’m not mistaken, UHs equipped with T400s were / are commonly called Twin Huey, a nickname derived from the nickname of this helicopter, Huey, itself derived from its initial designation, HU-1.

A labour dispute disrupted UACL’s activities. In August 1973, management had begun discussions with the union representing the staff, the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America. This powerful union affiliated with the American Congress of Industrial Organizations intended to obtain some concessions, including the delivery of an uncapped cost-of-living allowances and a right to refuse to work overtime. The main demand of the union, however, remained the payment of dues by all employees, whether members or not. This mandatory union check-off was / is better known as the Rand formula, named after Supreme Court of Canada justice Ivan Cleveland Rand, who concluded in 1946 that an employer had to deduct union dues at source even for people who were not members of a trade union.

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America planned to use the concessions obtained from UACL to get Pratt & Whitney Aircraft to offer the same benefits to its employees. UACL or, more precisely, United Aircraft refused to give in, even if many companies established in Québec applied the Rand formula, sometimes without enthusiasm it must be admitted.

In November 1973, union members rejected the employers’ offers and called for a strike. In early January 1974, many workers disrupted operations in the factory. About 20 of them were suspended. The management locked the doors and instituted a search of the personnel, thus initiating a lockout. Three days later, a second group of workers disrupted operations at the factory. The union then erected picket lines, even though a few hundred people who were not union members remained at work. A strike began. A number of clerical staff and engineers came in to support employees who wished to work. Attempts at conciliation and mediation failed. Over the weeks, UACL hired hundreds of strike breakers / scabs.

As these measures proved insufficient to ensure all deliveries of engines and spare parts, United Aircraft transferred no less than 70% of PT6 production to the factories of its Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and Pratt & Whitney Aircraft of West Virginia divisions, located in the United States. The American giant claimed that this measure allowed it to break production records.

Some, including American actress and activist Jayne Seymour “Jane” Fonda, accused it of wanting to break the union. Still others believed that United Aircraft placed less importance on the future of UACL than on the demands of the mostly American aircraft manufacturers whose aircraft required PT6s.

The move of the production equipment caused a stir. Many observers feared that production of the PT6 would not resume in Canada, despite the financial assistance provided over the years by the federal government. Many individuals raised the issue in Ottawa and Québec, in the House of Commons and the Assemblée nationale. A well-known bimonthly, The Canadian Aircraft Operator, put forward a strong commentary: “Canadian developed and manufactured high technology products are much more important to the national economy, and as symbols of national capability and pride, than the Canadian Football League. The Cabinet might consider this when putting their priorities in order.”

The monthly Canadian Aviation went even further: “If Ottawa is truly sincere in its announced attempts to secure a brighter future for the Canadian aircraft industry, then its next step must surely be to ensure that the United Aircraft of Canada Ltd. is brought under Canadian control. “

A comment if I may. Much of The Canadian Aircraft Operator’s commentary was seemingly directed at Marc Lalonde. The Minister of National Health and Welfare, Status of Women, and Amateur Sport then indeed paid quite a bit of attention to what was going on within the Canadian Football League – an organisation foreign to say the least to his (too?) heavy functions, but back to the strike.

Increasingly frustrated by the employer’s tactics, deemed too unfair by far, some strikers attacked scabs and employees who remained at work. At least 50 or so people were attacked between January and December 1974. Over 900 cars and nearly 150 homes suffered damage. Six small homemade bombs exploded at the factory site in August. The tension reached such levels that UACL had to call in helicopters in October to transport scabs.

That same month, various people organised a benefit show for the strikers. This 24-hour Automne Show brought together some of the best-known and most popular nationalist / sovereignist artists in Québec, from Pauline Julien to Louise Forestier, born Louise Bellehumeur, including Raymond Lévesque and Claude Dubois, born Claude André, not to mention the folk / progressive rock band Harmonium. A well-known and respected trade unionist, Michel Chartrand, held the role of master of ceremonies. Many other demonstrations of solidarity took place in Montréal, Québec, over the weeks.

While employer-union meetings took place more or less regularly throughout 1974, the fact was that a solution to the conflict proved problematic. The union, for example, wanted an immediate return to work. The employer could not accept this request. It had responsibilities towards its scabs, for example. The return and re-installation of production tooling sent to the United States would also take some time. Both the Commission parlementaire du travail et de la main d’œuvre and Québec’s minister of Labour, Jean Cournoyer, failed in their attempt to advance negotiations.

Out of resources, hundreds of strikers had returned to work in the spring of 1974. A letter from the American management of the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America sent in August accusing union leaders of having illegally cashed more than 200 strike checks was a turning point in that regard. The confidence of the strikers was shaken even if the money was apparently intended for an emergency fund created to meet their needs. Regardless, many strikers came to believe that the powerful American union wanted to break their morale in order to end a conflict which was costing them dearly. Indeed, they were not without knowing that American workers had accepted without too much difficulty the use of production equipment relocated at great expense by United Aircraft.

A little before mid-May 1975, 60 or so strikers entered a workshop with makeshift weapons. They intended to occupy it in order to force the firm to negotiate. Informed by their union leaders, around 2 000 workers from other firms came to the factory site. They overturned a few cars from the Longueuil police department and set one on fire. Discovering 2 employees hidden in the occupied workshop, the strikers announced that they had many hostages. The riot squad of the Québec provincial police force, the Sûreté du Québec, easily dispersed the workers outside the factory and entered the occupied workshop. Many strikers managed to escape. About 35 others were arrested after being seriously beaten. UACL’s plant sustained damage estimated at over $ 600 000.

A few days later, nearly 100 000 workers, it was said, from across Québec took part in a one-day sympathy strike organised by the Fédération des travailleurs du Québec, one of the major labour unions in Québec.

Even before the end of the month, Gilles Laporte, a special adviser to the ministère du Travail appointed mediator in March by the provincial government, submitted his report. He recommended that UACL re-engage all strikers who wished to return to work. The firm hesitated. It only wanted to re-hire a part of them. Management decided after a few days to re-hire the employees once they knew how many of them wanted to return to work. UACL, however, refused to take back the arrested strikers. Negotiations stumbled.

Eager to break the deadlock, 7 well-known and respected Québec personalities, including Claude Ryan, director of an influential Montréal daily Le Devoir, formed a neutral committee. They wanted to contact the strikers who had held up so far to find out their intentions. The union hesitated, then accepted. More than three-quarters of the strikers wanted to return to their jobs. In July, UACL proposed a return to work deadline deemed unacceptable. Negotiations stumbled again.

His patience at breaking point, the premier of Québec, Robert Bourassa, submitted a proposal to the 2 parties in August. UACL accepted it. In doing so, it pledged to take back all strikers who wished to return to work by the end of February 1976 – a promise broken in the forthcoming return to work protocol text. The seniority of all re-hired strikers was also adjusted to include the approximately 600 days that the strike had lasted. UACL did not promise to give the strikers the jobs and / or wages they had before the conflict. The fate of those arrested in May, a thorny subject if any, was in the hands of an arbitrator. Worse still, the firm refused payment of union dues by all employees.

Although deeply disappointed, the strikers voted in favor of this agreement by a strong majority. The UACL strike, one of the longest and most violent labour disputes in Canadian history, officially ended in late August 1975. Although found not guilty, the strikers arrested in May may not have been rehired.

While it was / is true that the UACL strikers paid dearly for their solidarity, the fact is that workers in Québec owe them a lot. The attitude of the Bourassa government towards the strikers contributed in fact somewhat to the first electoral victory of a sovereignist / pro-independence party, the Parti Québécois, in November 1976.

This new government, led by René Lévesque, a gentleman mentioned in a few times in our you know what since September 2018, passed a bill which made the Rand formula mandatory. It also passed a bill which banned the use of scabs during a legal strike.

Realising that its reputation had been heavily tarnished, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft of Canada Limited / Pratt & Whitney Aircraft du Canada Limitée, a company name adopted in May 1975 to help restore its image, carried on philanthropy in the Montréal region for many years.

The end of the strike led to the gradual return of PT6 production equipment to Canada. Life resumed its course in the workshops.

Around May 1986, Pratt & Whitney Canada Incorporated, a company name adopted in October 1982, and a Chinese state-owned firm, Zhōngháng Jì Jìn Chūkǒu Yǒuxiàn Zérèn Gōngsī, or China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC), signed a 5-year agreement to assemble a version of the PT6 from sub-assemblies made in Québec. These turboprop engines were intended for a small transport aircraft very similar to the aforementioned Twin Otter, the Y-12 of the aircraft manufacturer Hāĕrbīn Fēijī Zhìzào Gōngsī / Zhōngháng Gōngyè Hāfĕi Gōngsī.

In August 1993, PWC and Otkrytoye Aktsionernoye Obshchestvo “Klimov,” the Russian Federation’s largest turboshaft manufacturer, joined forces to found Pratt & Whitney / Klimov Limited. Established to become the leading manufacturer of civil limited power turboshafts in the country, the new firm was licensed to produce a version of the PT6 and a newer engine, the PW200. Indeed, Pratt & Whitney / Klimov began to develop a Russian version of the PT6. This project apparently led to nothing concrete. In August 1997, PWC acquired all the holdings of Pratt & Whitney / Klimov and founded P&W-Rus. The latter intended to develop turboprops, turboshafts and turbofans for the Russian market and neighboring countries. Again, this project apparently led to nothing concrete, for one reason or other.

In 2020, nearly 60 years after its first bench test, the PT6 remained one of the most popular turboprop / turboshaft in its class. It represented a turning point in the history of its manufacturer. In fact, this exceptional engine has changed the face of the aerospace industry around the world. Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft /… / Pratt & Whitney Canada, as well as the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and Pratt & Whitney Aircraft of West Virginia Divisions of United Aircraft, produced more than 51 000 civilian and military PT6 and PT6T Twin Pacs between 1960 and 2015. Over the years, more than 6 500 civilian and military operators based in more than 170 countries have used / use airplanes and helicopters equipped with these various types of engines.

The saga of one of these airplanes, the Saunders ST-27, was / is at the heart of an issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee put on line in August 2019.

Is this the end of the first part of this article, you ask, hopeful, my reading friend? Nay.

No later than the mid-1960s, Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft realised that the PT6 was attracting a lot of interest outside of the aerospace community. The Québec firm created an Industrial and Marine Division in January 1966 in order to develop industrial and marine versions of its engine known as the ST6.

This being said (typed?), Kongsberg Vapenfabrik Aksjeselskap, a Norwegian state-owned weapon manufacturing firm, worked with Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft / UACL as early as 1962 to develop a marine version of the ST6 gas turbine. This engine was intended at least in part for the propulsion of future fast attack craft which might have been of interest to the Norwegian navy, or Sjøforsvaret. A prototype, the Rimfakse cabin cruiser, began a series of very successful trials even before the end of the year. The Norwegian navy, however, decided to equip its new fast attack craft with diesel engines, just as in the past.

In February 1966, the very first turbine racing boat, the American Thunderbird Products Thunderbird, manufactured by Alliance Machine Company, competed in the Sam Griffith Memorial Race. Its crew won this open sea race held between Miami and Fort Lauderdale, Florida, without any difficulty. In fact, only 2 of the 30 or so boats at the starting line completed the race. The experimental status of UACL’s gas turbines, however, did not allow the crew of the Thunderbird to pocket the prize.

In the spring of 1969, Aluminum Company of Canada Limited (Alcan), a firm mentioned in a December 2019 issue of our you know what, took delivery of the Nechako, the largest aluminum-hulled boat manufactured in Canada to date. A small shipyard, Matsumoto Shipyards Limited of North Vancouver, British Columbia, manufactured this shuttle boat powered by a pair of ST6s and designed by the Project Development division of the aluminum firm. Alcan used the Nechako to transport passengers and cargo between certain facilities in British Columbia.

The United States Army had the privilege of sponsoring the first land application of the ST6. An unidentified firm converted a Consolidated Diesel Electric LARC V amphibious transport vehicle in 1964. The test program worked well but did not lead to a production contract.

The first truck with an ST6 was a snow plow used from 1967-68 to the mid-1970s by the British Columbia Department of Highways. This vehicle was not produced in series. The same went for the few experimental trucks and tractor trailers manufactured at this time by often well-known American, Japanese and West German companies.

Non-mobile applications of the ST6 included a wood chipper built in Québec by Domtar Corporation and an oil fracker made in the United States by Halliburton Company. Neither of these pieces of equipment completed in the second half of the 1960s went beyond the prototype stage.

In general, manufacturers and users of the aforementioned equipment were satisfied with the performance of the ST6. However, the diesel engines used at the time proved to be sufficient and less expensive to purchase and operate.

It is worth noting that a number of ST6s spun / spin in pumping stations that force gas or oil into pipelines in various parts of the globe.

Another application of the ST6 worthy of mention was undoubtedly the STP Special or Turbocar, a revolutionary 4-wheel drive racing car designed in great secrecy by the Paxton Division of STP Corporation. This manufacturer of gasoline additives and subsidiary of the American automaker Studebaker Corporation sponsored racing teams which took part in one of the most important automobile competitions in the world, the Indianapolis 500. The STP Special, or “Silent Sam / Whooshmobile,” the first turbine car to qualify on this legendary circuit, set 18 speed records during the race, to the chagrin of many fans of roaring racing cars who fiercely hated it. Only a slight mechanical problem unrelated to the ST6 caused its driver to withdraw from the race, minutes before a seemingly certain victory. Shocked by this performance and pressured by the owners of other racing teams, the United States Auto Club (USAC) rushed to change its regulations to limit the chances of success of cars equipped with a gas turbine.

The chief executive officer of STP, Anthony “Andy” Granatelli, returned to the attack in 1968, with no less than 5 cars fitted with an ST6, namely the STP Special, modified to meet the new standards, and 4 STP-Lotus manufactured by a well-known British firm, Lotus Cars Limited. A revolutionary 4-wheel drive vehicle, the Lotus 56 was one of the first racing cars to use a special aerodynamic shape which pressed the wheels against the ground to maximize grip.

Tragically, the driver of a Lotus 56, Michael Henderson Spence, killed himself during training, shortly before the Indianapolis 500. Fearing that it would be impossible to run high-performance turbine cars without putting the drivers’ lives in danger, famous American racing car designer and owner Carroll Hall Shelby withdraws the 2 cars he had entered in the race. A few days after the accident, the STP Special was destroyed during training. Its pilot was not injured, however.

The 3 running Lotus 56s easily qualified for the 1968 edition of the Indianapolis 500. Two of them actually set the fastest times in practice, much to the chagrin of the other teams. Only slight mechanical problems unrelated to the ST6 lead their drivers to withdraw in the middle of the race. Responding to renewed pressure from the owners of virtually all racing teams, USAC further tightened its regulations. Only gas turbines intended for automobiles would be able to participate after January 1970 in the races it supervised. No such turbine being available at the time, or even later, this type of engine was banned from circuits governed by USAC.

This being said (typed?), Lotus Cars used the aerodynamic shape of the Lotus 56 for its new Formula 1 car with a piston engine. A pilot of this Lotus 72, Karl Jochen Rindt, won the 1970 world championship of the Fédération internationale de l’automobile, after his death during a practice run. With many Grand Prix races won between 1970 and 1975, by racing giants like Emerson Wojciechowska Fittipaldi and Jacques Bernard “Jacky” Ickx, the few (6?) Lotus 72s produced by Lotus Cars more or less dominated the world of Formula 1 racing in the first half of the 1970s.

A modified Lotus 56 competed in three Formula 1 Grand Prix in Europe in 1971. Its poor performance meant that no other team subsequently embarked on the adventure of designing a turbine car.

It was around 1965 that one of the most important applications of the ST6 made its debut. This project had its origins in the growing interest of the United States Department of Commerce in intercity passenger transport using light, fast and comfortable trains powered by gas turbines. The Corporate Systems Center of United Aircraft, greatly assisted by a sister firm, the Sikorsky Aircraft Division of United Aircraft, designed a turbine train, in response to a competition launched by the United States Department of Commerce as part of the Northeast Corridor Transportation Project. It did this using a design and various patents from an American railway firm, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company.

United Aircraft signed contracts with the United States Department of Transportation (2 years) and Canadian National Railway Company (8 years) in January and March 1966, without building a single prototype – a daring strategy to say the least given its inexperience in railway material. The American giant thus undertook to supervise the construction of 7 TMT-7 TurboTrains, including 5 for the Canadian crown corporation, from its own resources it seems. If the trains that were to run in the United States were to be leased to their user, the status of Canadian TurboTrains is not entirely clear. If the United Aircraft marketing team got a little too enthusiastic in the discussions, the firm’s engineers might have been overconfident.

It should be noted that Canadian National Railway had been considering introducing modern and fast trains in the Toronto-Montréal corridor since at least 1964. Indeed, the involvement of the Canadian crown corporation was to a good extent due to the fact that it was under certain political pressures in order to meet the expected demand throughout the Exposition internationale et universelle de Montréal, or Expo 67, which was to be held from April to October 1967. Let’s not forget that Canada was celebrating its centenary that year, as Québec sovereignist groups were getting louder and louder.

The TurboTrain, which outperformed any other model considered, was a godsend to the marketing staff of Canadian National Railway. Their colleagues in the technical, operational and maintenance sectors showed less enthusiasm. Indeed, some doubted that the trains could enter service in 1967.

In fact, the majority of the members of a working group created for this purpose rejected the project submitted by United Aircraft in June 1965. The vice-president of sales and passenger service, Pierre Delagrave, one of the most dynamic figures of the Canadian crown corporation, refused this recommendation, however. He fought for weeks, much to the chagrin of the other vice presidents. Frustrated by the lack of decision, Delagrave accepted a job in another firm in the fall of 1965. To the surprise of many, the executive vice-president of Canadian National Railway approved in December the project submitted by United Aircraft. Better yet, he used Delagrave’s arguments to do so.

In any event, Montreal Locomotive Works Limited of Montréal, a subsidiary of American Locomotive Company, received the contract to manufacture 5 TurboTrains for Canadian National Railway.

The first TurboTrain, made in the United States by a declining rail industry giant, Pullman-Standard Manufacturing Company, began to roll in May 1967. It was nonetheless in Canada that the first TurboTrain entered service, however, in December 1968, well after the planned date. The first American train, or Metroliner, made its maiden voyage in April 1969, between New York City, New York, and Boston, Massachusetts.

The TurboTrain unfortunately proved ill-suited to the harsh winters which plagued the northern regions where it operated. Canadian National Railway trains had to be taken out of service 3 times, for example, in order to modify and / or repair them. Between December 1968 and January 1974, for example, these TurboTrains only ran for about 9 months. As a result, the crown corporation suffered significant revenue losses. On at least one occasion, the management of Canadian National Railway seriously considered dropping the whole thing. Worse still, perhaps, the many crossings and curves did not allow the Canadian TurboTrains to operate at full speed. They therefore did not arouse the enthusiasm of travelers who, for the most part, continued to take the plane or even their automobile. The Canadian TurboTrains resumed service for good in January 1974 but the damage was done.

Equally worrying for United Aircraft was the situation in the United States. National Railroad Passenger Corporation, or Amtrak, the semi-private American firm responsible for transporting passengers by rail from 1971, did not seem to have much interest in the TurboTrain. In fact, it turned to European manufacturers, primarily French, deemed better able to meet its needs. United Aircraft was so frustrated with this interest that it abandoned rail transport around 1974-75. Several American senators and / or representatives protested and denounced the attitude of Amtrak and the United States Department of Transportation. In any event, the Sikorsky Aircraft Division of United Aircraft, which had been in charge of the project for an undetermined date, provided UACL with all technical files relating to the project.

Amtrak retired its TurboTrains in 1976. The Canadian trains, operated since 1977 by VIA Rail Canada, the Canadian opposite of Amtrak, made their last trip in October 1982.

In the United Kingdom, Cushioncraft Limited used an ST6 to lift and propel an air cushion vehicle or hovercraft. This subsidiary of aircraft manufacturer Britten-Norman Limited mentioned in May 2018 issues of our you know what designed the CC-7, mentioned in those same issues, under a Ministry of Technology research contract.

The ST6 was also involved in an attempt by the federal government to start production of hovercraft on Canadian soil. The Bell Aerospace Company Division of the aforementioned American giant Textron completed a prototype of the Model 7380 Voyageur in 1971. All this talent was mentioned in a you know what of March 2018.

One of the most interesting derivatives of PT6 was the ASP-10. This compressor owed its origin to the development of an Air Cushion Landing System mounted on a de Havilland Canada CC-115 Buffalo short take-off and landing military transport aircraft of the Canadian Armed Forces. As you might expect, this whole story was mentioned in the aforementioned you know what of March 2018.

It should be noted that UACL produced hundreds of ST6s used as an auxiliary power unit aboard the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, a wide-body airliner which first flew in November 1970.

Yours truly intends to address an aspect of the PT6’s aeronautical career in the second part of this article. What aspect is that, you ask? It’s a secret.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)