Montréal has its first aeroplane: The Blériot Type XI of Jean Versailles and William Carruthers

Welcome, my reading friend, welcome.

May yours truly propose that we listen to our passion for wings on this day in May? We have, after all, ignored it for some weeks. Any objections?

Objection denied.

The year I intend to bring to your attention being 1910, put on your time travelling goggles and take a deep breath.

In mid-May of that year, a brand new Blériot Type XI, a French aeroplane type made famous by Louis Charles Joseph Blériot’s crossing of the English Channel in July 1909, a world first, arrived in Montréal, Québec, Canada’s metropolis.

And yes, Blériot was mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since October 2018.

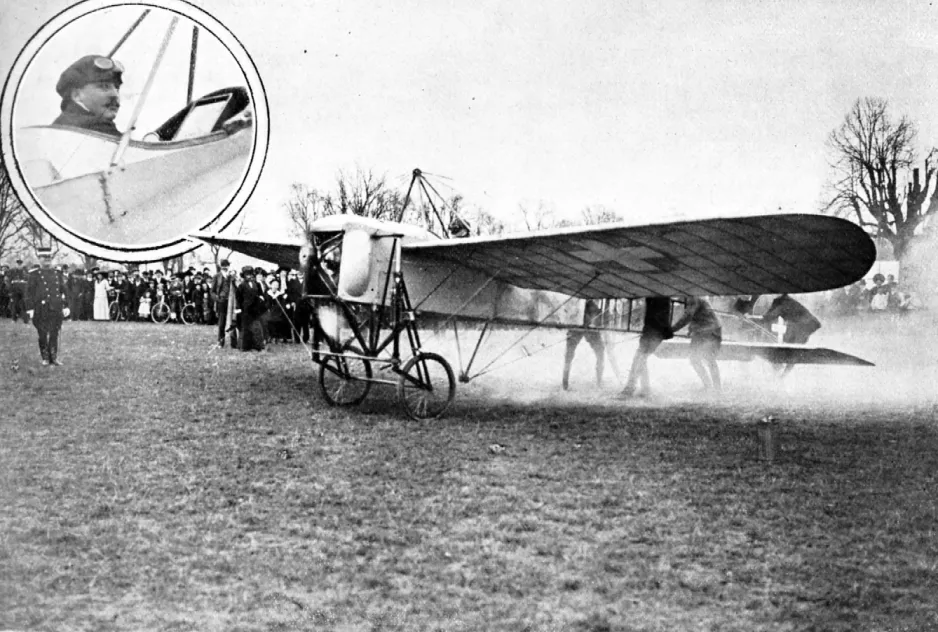

A typical Blériot Type XI flown by Swiss aviator Attilio Maffei to promote the Swiss national subscription for military aviation. Anon., “Maffei vole pour l’aviation militaire à Soleure et à Sion.” La Suisse Sportive, 17 May 1913, 3 067.

The proud owner of the Type XI which had arrived in Montréal, Jean Versailles, a well-known and wealthy real estate agent, sports patron and keen sportsperson (yacht, motorcycle and automobile racing for example), was / is seemingly the first private individual in Québec / Canada to own an aeroplane. His passion for wings seemingly dated from 1909.

The Type XI in question had crossed the Atlantic, no, not in flight, but safely stored in the cargo hold of the SS Sardinian, a mixed passenger and cargo ship owned by the Montréal-based Allan Line Steamship Company Limited. A news report stated that this flying machine was to be used by Blériot himself, until Versailles’ order came in that is.

Yeah, right.

Sorry.

Did you know that the Sardinian was the ship aboard which Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, a handsome, brilliant and ambitious young Italian mentioned in December 2018 and April 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, crossed the Atlantic Ocean, in November / December 1901, with his wireless telegraphy / radio equipment, to set up a station at St Johns, Newfoundland – an independent and sovereign Dominion at the time? Small world, isn’t it?

In December, Marconi and his assistant heard the first radio signal ever sent across the Atlantic – or so they claimed. You see, my reading friend, this world famous experiment, this turning point in human history, may be no more than a hoary old myth. The atmospheric conditions were such and the equipment used so primitive that many experts in radio wave propagation believe that Marconi and his assistant wanted, dare one say needed, to hear something so much that they mistook atmospheric noise for the signal they were waiting for.

Would you believe that the collection of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes 4 kites that may, I repeat may, have been used during this experiment? But back to our story.

Versailles was very pleased indeed with his acquisition. You see, he had to jump through quite a few hoops to get his hands on an aeroplane. Versailles had ordered a small number of machines from 2 French aeroplane manufacturing firms. The latter, however, could not honour their part of the contracts. In other words, neither firm could deliver an aeroplane to Versailles.

Deeply annoyed, Versailles got what he wanted through G. Husson, the director of Montréal-based Franco-American Automobile Company, a firm mentioned in a March 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee who happened to be the Canadian representative of the Établissements Blériot Aéronautique, a sister / brother company of the Société anonyme des Établissements L. Blériot, a well-known French manufacturer of headlamps for horse-driven carriages and horseless carriages / automobiles.

At this point, yours truly would like to apologise for not pointing out that Franco-American Automobile should not be confused with 2 short-lived American firms, Franco-American Automobile Company and Franco-American Car Company, founded in the early years of the 20th century.

The arrival of the Type XI caused a sensation in Montréal. It made the front page of La Presse, one of the most important French language daily newspapers in Québec / Canada. The presence of this aeroplane also whetted the appetite of several individuals who asked Versailles if he might be willing to sell the Type XI.

Within days, Versailles’ interest in aviation led to his appointment as director of a committee set up by the Automobile and Aero Club of Canada Incorporated, a wealthy organisation, to organise aeronautical events in Montréal.

Interestingly, a good size article published around that time in La Presse stated that the first flights of a powered heavier than air flying machine, in other words an aeroplane, had taken place… 3 and a half years before, in October and November 1960, sorry, 1906, near Paris, France. The first one was little more than a hop but the second one covered an astonishing distance of 220 metres (720 feet).

You will remember that the pilot of said aeroplane, a rich and fearless Brazilian mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since November 2018, Alberto Santos Dumont, established, in November 1906, the first 3 world records (distance, altitude and duration of flight) made aboard an aeroplane to be approved by the Fédération aéronautique internationale, the Paris-based world governing body for all manners of aeronautical records mentioned several / many times in that same outstandingly significant publication since January 2018.

You and I both know that Santos Dumont was / is not the first human being to make a controlled and sustained flight in a powered aeroplane. This honour belonged / belongs to Orville and Wilbur Wright, 2 world famous aviation pioneers mentioned several times in our you know what since August 2018.

If truth be told, the odd looking machine piloted by Santos Dumont was, well, not really controllable, but back to our story.

The Type XI was scheduled to fly, somewhere northeast of Montréal, at a hippodrome perhaps, in the late spring or early summer of 1910, at the latest. Versailles did not know if he would pilot the aeroplane himself or hire someone to take his place. While the latter seemed the preferable option given that Versailles had no experience whatsoever in piloting any type of flying machine, the truth was there was no one in Montréal who had any heavier than air piloting experience. A journalist working for La Presse wondered if Versailles might want to choose an individual, all right, all right, a man who knew how to pilot a balloon.

Oddly enough, and I will readily admit my lack of faith in personkind might be all too visible here, it so happened that La Presse may have counted among its staff a person who knew how to pilot a balloon. This rara avis was Émile Auguste Albert Barlatier, the French born mechanical sports editor of the Montréal daily from late 1910 or early 1911 onward, and an employee of the newspaper for some time before that from the looks of it.

Would you believe that Barlatier may, I repeat may, have been an employee of La Presse since 1905? This would explain the fact that he seemingly made a balloon flight near Montréal in November of that same year with another employee of the daily, Lorenzo Prince.

The catch with that information is that I cannot find a thing on this flight in La Presse, which is very suspicious. Indeed, I seriously think that this flight may not have taken place, and that Barlatier came to Canada much later.

Anyway, in 1905, Prince was a household name in Canada’s metropolis. You see, back in May, June and July 1901, he and the La Presse’s city editor, Augustin Marion, had taken part in a race around the world initiated by the famous Parisian daily newspaper Le Matin. Said newspaper, mentioned in an April 2019 of our you know what, wanted to see if it was possible, in 1901, to beat the time needed by fictional hero Phileas Fogg to go around our circular, yes, yes, circular, not flat, planet.

The author of Around the World in Eighty Days, a novel published, in French, in 1872, Jules Gabriel Verne, a gentleman mentioned in many issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since June 2018, indicated that he was convinced that Fogg’s time could be beaten. He wished the best of luck to the writer and Le Matin journalist, Gaston Stiegler, who would make the attempt.

You will remember that the motion picture Around the World in Eighty Days was mentioned in a May 2019 issue of our you still know what.

In the end, Stiegler beat Fogg’s time. Indeed, he completed the Paris-Paris journey in less than 64 days.

As far as yours truly can figure out, Prince completed his Montréal-Montréal trip around the globe in 63 days. In other words, he did it faster than Stiegler. This being said (typed?), Le Matin and the rest of France / the world (?) seemingly could not have cared less.

What about Marion, you ask, my concerned reading friend? Fear not. He also completed his trip around the globe. Marion arrived in Montréal a month or so after Prince, however, and he was not amused. You see, he had been arrested and detained by the Russian authorities as the dynamic duo from Québec was travelling on the Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga, in the other words the Russian-built and controlled railway line crossing Manchuria, a vast region of North-East Asia with poorly defined limits. Prince had somehow convinced said authorities that he was as white as snow. I can only presume that his companion and boss was in agreement.

Dare I interrupt this pointless peroration to state that Barlatier was mentioned in March and May 2019 issues of… I should not, you say? Very well. Let’s move on.

But not now.

In 1903, in Marseille, France, Barlatier, a journalist at the time from the looks of it, and a lawyer by the name of Henri Blanc began to envision the possibility of building an aeroplane. In 1905, they flew kites. The following year, Barlatier and Blanc tested a powered scale model of their aeroplane, whose wings were inspired by those of the magpie. In late 1906, thanks to the financial assistance of a local businessman and keen sportsperson, Morpugo Lavalli, they completed a monoplane inspired by that model. It proved unable to fly. Barlatier and Blanc may have tested another powered scale model in 1907. They tested a second monoplane in March 1908. It too proved unable to fly. Barlatier, president of the Automobile Club de Marseille at the time, seemingly decided to call it quits not too long after.

Blanc, on the other hand, designed a new aeroplane in which he was able to take off, briefly, in August 1909. This machine later made some brief flights. It was not all that good, a characteristic it shared with the great majority of the aeroplanes designed around that time.

Do you have time for a brief digression, my reading friend? I do not want to be pushy.

Do you remember a brief peroration on the French word tourte in an April 2020 issue of our you know what? No? Sigh. Never mind. Would you believe that Barlatier’s father, industrialist and composer Albert Auguste Marie Barlatier, worked several times with a well-known songwriter / dramatist / composer named Francis… Tourte, born Louis François Tourte? Ours is a very small world indeed, is not it?

In fact, you probably wonder if, like the famous Captain Jack Sparrow, a gentleman (?) mentioned in September 2018 and October 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, yours truly plans it all, or just makes it up as I go along. You decide.

Now back to our story. Versailles indicated that the Type XI would soon be transported to Pointe-aux-Trembles, near Montréal, where he owned huge tracts of land, after payment of all custom fees of course. The first flight of this aeroplane would be an event to which he would invite all Montrealers. There were some / many who thought / hoped that said flight would take place before the end of May.

Would you believe that rumours circulated to the effect that a large Montréal organisation, either private or public, would offer a magnificent prize to the individual who would perform the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered aeroplane in Montréal?

“It is an era of progress that is beginning, stated an unnamed journalist of Le Devoir, a new Montréal daily newspaper which still existed as of 2020. Before long one will be able to holiday by aerial means. Who knows if the delivery of mail will not be done soon by this fast and direct means.”

That same unnamed journalist mentioned that the aforementioned Blériot would not be visiting Canada’s metropolis in 1910. Negotiations to that effect had recently failed. One of his engineers, a brother of Marie Joseph Adrien Leblond de Brumath, the principal of the Académie commerciale catholique of Montréal, a commercial school I believe, would not be coming either. And yes, negotiations to that effect had also recently failed.

A total digression if I may and I do apologise but, as the friendly but somewhat deranged Sparrow said so well, yours truly could not resist.

And here is the digression. For some time (weeks? months?) during 1910, La Presse offered prizes to children who recognised their photograph in a special column of the newspaper and came to its offices. Said prizes were a sum of $ 1.00, a pretty good sum for 1910, and a Chantecler aeroplane, a toy invented by Montrealer J. Renaud-Egret.

It is possible that the name of this toy was inspired by the title of a well-known but not very popular 1909 French play entitled, err, Chantecler, by Edmond Eugène Alexis Rostand. This renowned poet and dramatist had written the very popular 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac, by the way, and yes Virginia, there was a Cyrano, mentioned in a February 2018 issue of our you know what.

Back in the 17th century, French author / satirist / soldier Hector (?) Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac imagined journeys to other worlds. In The Comical History of the States and Empires of the Worlds of the Moon and Sun, published posthumously in 1657, in French, for example, the hero of the story was lifted off the soil of France by the dew contained in bottles strapped around his waist. While it is true that this interplanetary journey proved unsuccessful, a successful landing was made in New France.

Our hero then built an ornithopter, in other words a flapping wing flying machine, in Québec, the capital of said New France. The first test flight ended with a painful crash. Back in his room, our hero put beef bone marrow over much of his bruised body. Meanwhile, soldiers who had found the ornithopter in the woods brought it to the city square where they attached firework rockets to it, to celebrate the birthday of Saint John the Baptist, on 24 June.

Realising what about to happen, our furious hero rushed to his machine but could not remove the rockets before the first ones went off. The ornithopter took off and began to climb, and climb, and climb. It eventually fell back to Earth but our hero was so close to the Moon by then that the attraction between our neighbour and the bone marrow, a scientifically proven fact and if you believe that I have a bridge I’d like to sell, was so great that he ended up there, making a safe landing of course, to continue his adventures, but back to our you know what – the story of course.

You may be saddened, or not, to hear (read?) that Versailles took possession of his Type XI only in late May, almost 2 weeks after the ship carrying it arrived in Montréal. Why the delay, you ask? To quote Hellboy, the grumpy nacho and cat loving hero of the very popular eponymous 2004 movie, let me go ask.

[Music of the American television game show Jeopardy playin’ in your noggin.]

Greetings, my reading friend. The reasons why Versailles’ efforts to take possession of his Type XI proved so time consuming, in French chronophages (Hello, EP!), were / are a tad convoluted. While it is true that bureaucracy was / is (will be?) bureaucracy, it looks as if certain unnamed individuals proved somewhat uncooperative, for unknown reasons. A representative of La Presse may have pulled a few strings to help things along.

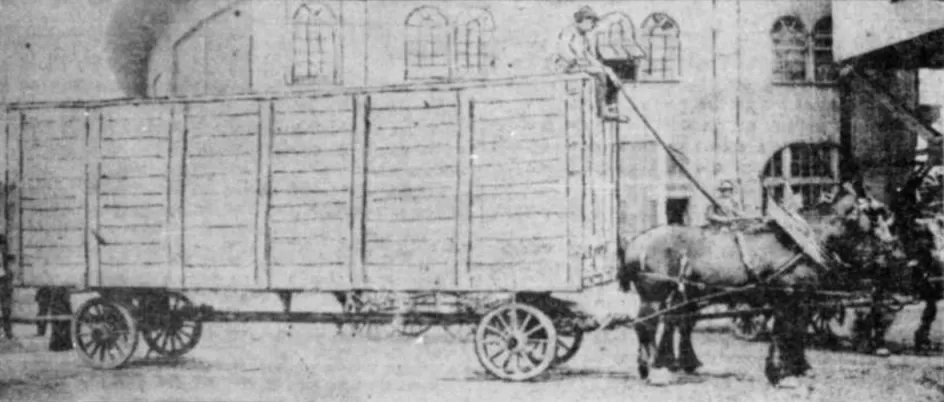

In any event, the huge crate containing the partly disassembled aeroplane left a hangar in the harbour of Montréal and was hoisted aboard a specially equipped horse-driven truck which belonged to Shedden Forwarding Company Limited of Montréal.

The crate slowly made its way to Pointe-aux-Trembles, with an automobile driven by La Presse representatives to keep it company. It was raining cats and dogs, which was not necessarily good news for the content of the crate.

In the end, the crate and its content arrived at Pointe-aux-Trembles. The crate was lowered to the ground and opened, besides the hangar which had been built to house the Type XI. The aeroplane was then carefully extracted from the crate. It would be ready for its first flight 1 or 2 days later, or so claimed La Presse.

The newspaper noted with some sadness that, while French aviation could count on several wealthy patrons willing to offer important prizes to pilots, no one in Montréal had offered so much as a medal to reward the as yet unknown individual who would make the first flight of a powered aeroplane in Québec.

Given this situation, La Presse announced in very, very early June that it would give a magnificent silver cup to the individual who would make the first 1 mile (1.6 kilometre) flight in a straight line, without any intermediate stop, in Québec.

A dramatic turn of event changed the game even before the month of May came to a close, however. Versailles agreed to sell his Type XI, under certain conditions, to a Montrealer by the name of William Carruthers. This well-known grain operator, horse race enthusiast and automobile patron mentioned in a March 2020 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee did not want to say how much moolah / dough had been spent to acquire said aeroplane. Carruthers did, however, indicate that the Type XI would be flown at Pointe-aux-Trembles soon after his return from a trip to the United States.

What is odd about an article published in La Presse in late May is the fact that it seems to say that the Type XI was not yet in Pointe-aux-Trembles and that the hangar at the site was as yet incomplete. Yours truly must admit that I am quite puzzled. Let us go on a limb, my intrepid reading friend, and choose as a working hypothesis the possibility that said article was / is inaccurate.

In any event, Carruthers’ Type XI had yet to take to the air when it went on display for a brief period of time, in June, at Dominion Park, one of the largest amusement parks in Canada, located some distance from downtown Montréal. J. Sullivan, an electrician working at said park who was deeply interesting in aviation, was on hand whenever he could (Hello, museum volunteers from around the world, and thank you!) to answer questions from the public.

How about Versailles? Was he abandoning aviation, you ask, my reading friend? Nay, say I. Indeed, Versailles ordered a larger aeroplane, a biplane this time, from the first aeroplane manufacturing firm in Europe, and the second in the world, after that of the aforementioned Wright brothers, Appareils d’aviation Les frères Voisin. He may, I repeat may, have done so through the Canadian representative of this French firm, the equally aforementioned Franco-American Automobile.

When the Type XI was finally assembled, in very, very late May, Le Presse described this fact as the beginnings of aviation in Canada. You and I both know that this was / is not true. One could argue that aviation in Canada began in February 1909 with the controlled and sustained flight of the Aerodrome No. 4 Silver Dart.

This flight was made by a young Canadian engineer, John Alexander Douglas McCurdy, the Silver Dart’s designer. This American-made aeroplane was the most successful machine developed by, you guessed it, the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), a group founded in Canada in 1907 by Scottish American, yes, yes, American, inventor Alexander Graham Bell. And yes, my reading friend, you are quite right in thinking that Bell, McCurdy and the AEA are known to us. They were mentioned in many previous issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee:

- McCurdy, since September 2017,

- Bell, since October 2018, and

- the AEA, also since October 2018.

But back to our Type XI.

Its engine ran for the first time in North America in very, very late May, on the day the aeroplane was finally completed actually.

Versailles climbed aboard the Type XI and was photographed by one of the people sent by La Presse to immortalise this auspicious occasion. The aeroplane’s new owner, the aforementioned Carruthers, was also there, as was the equally aforementioned Husson and several / many other people.

An unnamed journalist from La Presse stated that he was sure that aeroplanes would soon be used in large numbers. They were after all far superior to airships / dirigibles and less annoying than automobiles, which scared / injured / killed both pedestrians and animals and required good quality roads.

As was the case in all major cities of the Western world, aviation, in 1910, was attracting a fair amount of attention in Montréal.

What could well be the city’s first aeroplane manufacturing firm, the Compagnie de moteurs et d’aéroplanes Valois, came into existence, on paper only from the looks of it, in May 1910. Its promoters were well known Montrealers. They included the manager of the city and 3 lawyers. One of these was none other than Robert Taschereau, a close relative of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, minister of public works in the Québec government led by Lomer Gouin. Rather old in 1910, Achille Valois seemingly completed no more than a scale model of his multiple wing vertical take and landing aeroplane.

The individual who gave his name to the Compagnie de moteurs et d’aéroplanes Valois came to Québec around 1884. Head layup person with Marinoni Société anonyme, a French firm and a pioneer in the production of rotating presses for newspapers, Valois installed one of these (very?) large machines in the shops of La Presse. Ours is a small world, don’t you think, my reading friend? He seemingly remained in Canada’s metropolis, where he supervised the maintenance of said rotating press during an unknown number of years.

What could well be Montréal’s second aeroplane manufacturing firm, International Aviation Association Limited, came into existence, again on paper only from the looks of it, in June 1910. Its mandate included the production of various types of flying machines (balloons, aeroplanes, etc.), the organisation of air meets, etc., etc., etc. The firm’s promoters may not have been as well-known as those of the Compagnie de moteurs et d’aéroplanes Valois. International Aviation Association may not have produced so much as a scale model of the flying machines it had planned to produce, but back to our Type XI. Again.

Yours truly would be remiss if I did not mention that Carruthers’ Type XI was involved in one of the most significant aeronautical events held in Canada before the First World War, and the very first air show / meet held in this country. Said event was the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, held between 25 June and 5 July 1910. And yes, my reading friend, that was a lot of held.

To some extent, the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal owed its existence to another event, an annual event, the 1910 Motor Show held in Montréal in March – an event mentioned in a March 2020 issue of our you know what.

The presence of 2 aeroplane at this event had created quite a stir and its organisers concluded it was high time that Canada’s metropolis offered its citizens the chance to see pilots and aeroplanes in action. Other community leaders agreed. The aforementioned Automobile and Aero Club of Canada got to work. Incidentally, the site chosen was at Pointe-Claire / Lakeside, about 25 kilometres (15 miles) of downtown Montreal, near the shores of Lake Saint Louis.

You may delighted to hear (read?) that Carruthers’ Type XI was not the only aeroplane of its type present at the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal. This second Type XI also belonged to a Montréal businessman and well-known motorist, R. Baker Timberlake, who may have intended to teach himself how to fly during the air meet.

Carruthers’ aeroplane, on the other hand, was to be piloted by a little known French aviator and mechanic named Paul Miltgen, also spelled Miltzen, Miltjen, Miltjean and Mietgen, and sometimes referred to as Gustave Milgen, who had been hired expressly for this job.

Miltgen had begun his involvement in aviation in 1909. In October of that year, this still novice aviator arrived in the United States with a Type XI, quite possibly the very first foreign aeroplane brought to that country. American newspapers reported that this aeroplane belonged to Ralph Saulnier, the brother of a famous French aviation pioneer by the name of Raymond Victor Gabriel Jules Saulnier, then chief mechanic at the Établissements Blériot Aéronautique.

The catch with that information was / is that Ralph is not a very French name. Indeed, it looks as if this gentleman was not related in any way to Saulnier. Yours truly wonders if Saulnier, the American one, was not, in fact, an American resident / citizen who hoped to demonstrate the Type XI in order to sell a few examples of this type of aeroplane to wealthy Americans.

Incidentally, his Franco American secretary, Marie Sperber, very much wanted to make a brief flight aboard the Type XI. This plucky young woman had proved able to disassemble and reassemble the engine of this aeroplane. She seemingly did not get her wish. Pity.

Miltgen may, I repeat may, have made a few (2?) brief flights in New Jersey in the fall of 1909. In mid-October, either before or after these alleged flights, one of the hecklers who had called him a bluffer and a fake allegedly threw a brick at the Type XI as the French pilot was getting ready to take off. This brick was thrown with such force that it broke the propeller and damaged the engine.

Around that time, slightly before or after, a well-known Washington, District of Columbia, department store, S. Kann, Sons & Company, indicated it wanted to put the Type XI on display, a project under the supervision of the president of French-American Toy and Novelty Manufacturing Company. Interested in aviation since 1903 or so, Ladis Lewkowski supervised there the production of, among other things, flying model aeroplanes. Yours truly cannot say if this project came to fruition. Somehow, I doubt it and here is why.

Saulnier, the American one, was sued in October 1909 by the aforementioned Wright brothers, for patent infringement. They, after all, had invented a control system which made controlled flight possible. The Wrights wanted damage payments and the power to destroy the Type XI. Saulnier was one of the many individuals sued by the Wrights – an unfortunate episode known as the patent war which put the brakes on the development of aviation in the United States before the First World War.

If yours truly may be permitted a few words, this battle was not the Wright’s finest hour.

Saulnier, the French one that is, later cofounded the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier and the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Saulnier, one of the most significant French aircraft manufacturing firms of the pre-Second World War era, and…

What is it, my reading friend? You fail to see why yours truly is busting your chops with this twaddle? Well, did you know that the Borel Morane monoplane on display at the magnificently amazing Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, a sister / brother museum of the aforementioned Canada Science and Technology Museum, was seemingly made by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel-Saulnier? This Borel Morane monoplane is the oldest surviving aircraft to have flown in Canada, as we both know.

All but identical aeroplanes produced between 1910 and 1912 by this company and its predecessor, the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Borel, were confusingly known as Morane, Morane Borel and Borel Morane. Some witty persons even called them Morel Borane. Similar machines were also made in 1912 and later by the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Morane-Saulnier and the Société anonyme des aéroplanes Borel, but that’s not all. Would you believe that a Société des aéroplanes Raymond Saulnier existed in 1909-10?

So, have I succeeded in thoroughly confusing you, my reading friend? Yes? That’s good to hear (read?), because the history of aviation before the start of the First World War, in 1914, can be very confusing indeed.

All of these French aeroplane manufacturing firms were of course mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Of course.

Walter Richard Brookins, 1 of the 4 pilots of the aforementioned Wright brothers’ recently formed demonstration team present at the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, was the first aviator to take to the sky, on 25 June, the first day of the air meet. Miltgen was one of the people who helped prepare his biplane for takeoff.

Scheduled to lift off right a few minutes after Brookins, the French pilot was unable to do so on his first attempt. One the wheels of the Type XI had dug into a deep furrow. Miltgen’s second attempt went swimmingly and the crowd cheered. This was seemingly the first flight of the aeroplane since its arrival in Québec.

Two rather different versions of what happened next were published in La Presse and another Montréal daily newspaper, Le Canada.

According to the former, Miltgen realised that the rudder was not working almost immediately after takeoff, while the Type XI was still flying quite low. Unwilling to crash on the nearby catapult used to launch the Wright biplanes, he cut the engine. A combination of the tilting of the nose caused by Miltgen’s attempt to turn and of the weight of the aeroplane steepened its angle of descent.

According to the latter, the Type XI’s engine stopped very soon after takeoff, while the aeroplane was still flying quite low. Realising that any attempt to glide back to earth could result in a collision with said catapult, Miltgen steepened his angle of descent.

n any event, the Type XI crashed. The crowd held its breath, fearing the worst.

Almost miraculously, Miltgen walked away all but unhurt from this rather spectacular accident. The Type XI, however, was quite seriously damaged (shattered propeller, fuselage broken in 2 and separated from the wings, etc.).

Carruthers declared to journalists that he had been far more concerned with Miltgen’s condition than that of his aeroplane. If reparable, the Type XI would be repaired. If unrepairable, it would be put aside and replaced. As things turned out, the aeroplane was repairable. Work seemingly began the very day of the accident.

It is worth noting that, before his flight, Miltgen had indicated to at least one journalist that the Type XI was in rather bad shape when he picked it up at Dominion Park. The aeroplane had been moved in a somewhat careless fashion since its arrival in Québec and it had not been properly protected from the elements. There were even a few missing pieces. Miltgen had, however, done all he could to make the Type XI fully airworthy. Even so, the rudder did not seem to work too well and the wings did not seem perfectly symmetrical. All in all, Miltgen was not a happy camper when he climbed aboard the Type XI on 25 June.

In any event, Carruthers’ Type XI was deemed airworthy as of early July.

A teenage American airship pilot who had lost his mount on 27 June, Cromwell Dixon, had a close call when he took off aboard this machine, on 4 July, the American national holiday – his first flight in an aeroplane. Impressed by the courage he had shown a few days before, the star of the Grande semaine d’aviation de Montréal, France’s Count Jacques Benjamin Marie de Lesseps, took Dixon under his wing and may have given him pointers on how to fly an aeroplane. After a few takeoff attempts, the budding aviator managed to get into the air, barely missing the grandstand and causing quite a scare. Dixon completed this brief and rather wild flight with an awkward landing in a farmer’s field. His mother, who, as usual, was with him, but on the ground, was simply beside herself.

By the way, Carruthers’ Type XI also participated in the Toronto air meet which was held between 8 and 16 July, near Weston, about 16 kilometres (10 miles) from downtown Toronto, Ontario, on a model farm owned by a mining magnate, William G. Trethewey. It then had an American pilot named John Gale Stratton. This gentleman could not fly during the first days of the air meet, however, as he had to repair the damage suffered by the Type XI during its (train?) journey between Montréal and Toronto.

Stratton soon experienced difficulty controlling the aeroplane on its first attempt to fly, on 12 July, before the start of the day’s activities. He crashed among some trees, or between a pair of them. If Stratton walked away from this accident with an arm injury, the aeroplane was all but wrecked. Someone (seriously?) suggested that it would have to be shipped to France for reconstruction. One has to wonder if Carruthers’ Type XI flew again.

And so, once again, the Men in Black saved the people of Earth… Sorry, wrong ending.

Have a nice week.

And one more thing, if yours truly may permitted to quote police lieutenant Columbo, played on television by the irreplaceable Peter Michael Falk. The Voisin biplane mentioned above, you know, the one ordered by Versailles, yes, that one, well, it never made it to Montréal.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)