Jules Gabriel Verne would not have been amused: From the Earth to the Moon

May I begin this article by offering you my most sincere salutations, my reading frfiend? I am very pleased indeed to be with you again. If yours truly may paraphrase the title of a rather popular 1991 song by the American hip hop trio Salt-n-Pepa, let’s talk about space. More specifically, let’s talk about a forgotten space movie whose premiere occurred 60 years ago this month, in other words in November 1958.

From the Earth to the Moon was an adaptation of a well known novel, From the Earth to the Moon, direct in 97 hours 20 minutes, published in French in 1865. Indeed, it was 1 of the 9 motion pictures inspired by novels written by one of the founding fathers of science fiction, France’s Jules Gabriel Verne, which hit theatres between 1954 and 1962. The others were 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, in 1954, Around the World in Eighty Days, in 1956, Journey to the Center of the Earth, in 1959, Master of the World, Mysterious Island and Valley of the Dragons, in 1961, and Five Weeks in a Balloon and In Search of the Castaways, in 1962.

Yours truly did / does not care much for some of these movies. They were too silly. A few were really great, however, but I digress, one of my many faults. And yes, that was a very, very brief quote from the superb 2010 movie The King’s Speech. And yes again, my attentive reading friend, 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, the novel that is, not the film, was mentioned in July and September 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Why Vernian movies, you ask? Well, why not? On the one hand, movies based on Verne’s novels might attract science fiction and / or adventure fans. On the other hand, the aura surrounding Verne’s name might give movies based on these same novels a certain patina of dignity and distinction. These same factors help explain why movie studios also adapted 3 novels by Herbert George Wells in the 1950s and 1960s. The movies that resulted from this work were The War of the Worlds, in 1953, The Time Machine, in 1960, and First Men in the Moon, in 1964. Now that I think about it, I wonder if Verne’s books were not in the public domain, which would have eliminated the need for payments to his estate.

Interestingly enough, an American screenwriter, producer, director and actor announced in 1948 that he was considering the possibility of turning From the Earth to the Moon into a movie, tentatively entitled Trip to the Moon. William Castle, born Wilhelm Schloss, Junior, seemingly changed the title to Destination Moon. A Hungarian-American producer and director named George Pal, born Marczincsak György Pál, took on the project and the rest, as they say, is history. Who these “they” were / are, I have no idea, but I digress. And yes, my reading friend, Pal produced one of the Wellsian movies mentioned above, namely The War of the Worlds. Incidentally, yours truly is considering the possibility of pontificating on Destination Moon, a classic science fiction movie mentioned in a September 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, at some point in the future, but back to our story.

The plot of the movie From the Earth to the Moon would be familiar to the countless millions who have read Verne’s novel over the past 150 years. The opening credits, printed in gothic letters on the slowly turning pages of a large book, were admittedly a bit tacky. One has to wonder if they diminished the impact of the historical context of the story, which began soon after the end of one of the most terrible conflicts of the 19th century, the American Civil War (1861-65).

In any event, the film really got under way with an announcement by an American, Victor Barbicane, that he had invented an explosive of unparalleled and unprecedented power. An American metallurgist who despised this munitions manufacturer poured ridiculed on his claim. Stuyvesant Nicholl seemingly could not accept that Barbicane had done nothing to help the Confederate States of America (CSA) win the American Civil War. At the risk of stirring controversy, may I be permitted to ask if the slave holding southern states deserved to win? And yet, there were powerful groups in the United Kingdom and Canada, the pre 1867 one of course, that favoured the CSA. Why would anyone want to work with the CSA was / is beyond comprehension. It had to be a question of money.

In any event, Nicholl bet $ 100 000, a titanic sum at the time, that a metal of unparalleled and unprecedented strength that he had perfected would not be destroyed by Barbicane’s Power X, as the new super explosive was called. The latter accepted the challenge. Using a rather unimpressive cannon, he pulverised a thick plate made with Nicholl’s super metal. The demonstration also smashed a small mountain behind the test site. If I may steal a phrase from a British monarch, Nicholl was not amused.

And no, it is by no means certain that Queen Victoria, born Alexandrina Victoria Hanover, spoke these words. According to some, the monarch in question was Elizabeth I, born Elizabeth Tudor. Chances are we may never know for sure. Indeed, neither of the queens may have said these words, but back to our story.

Before we get there, I wish to point out that Power X was a liquid somewhat similar in appearance to ginger ale. You may be pleased to hear (read?), or not, that John James McLaughlin, the founder of Canadian soft drinks giant Canada Dry Ginger Ale Incorporated, was the brother of Robert Samuel “Sam” McLaughlin, founder of McLaughlin Motor Car Company Limited, an ancestor of General Motors of Canada Limited (GMC), a subsidiary of an American car manufacturing giant, General Motors Corporation.

Would you believe that GMC made 2 very special automobiles for the 1927 royal tour made in Canada by the Prince of Wales, then heir to the British throne, and his brother, the Duke of York? And yes, my royalist reading friend, the Duke of York, by then King George VI, born Albert Frederick Arthur George “Bertie” Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, was the main character in the aforementioned movie The King’s Speech. Better yet, in 1939, GMC completed 2 more very special cars for another royal visit, the first made in Canada by a reigning monarch, you guessed it, the equally aforementioned King George VI. Two of these 4 automobiles, one from each visit, have been preserved by the Canada Science and Technology Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, but back to our story. Again. Apologies.

It so happened that Barbicane got the idea of hitting the Moon with a shell filled with Power X in order to set off an explosion that would be visible from the Earth. President Ulysses Simpson Grant sent him a letter requesting that he put aside this project, and his invention. The governments of several countries, it seemed, feared the power of the new American super explosive. Worse still, Barbicane’s shell might miss the Moon and crash on Earth, causing numerous fatalities. Such a disaster could be construed as an act of war. Barbicane abided by the wishes of the President, and was promptly vilified by his backers and by members of the public.

At some point, Barbicane discovered that pieces of Nicholl’s super metal shattered by Power X had somehow been transformed into an extremely light and strong ceramic. The idea came to him that this material could be used to build a shell / spacecraft in which people could travel to the Moon, land there and presumably come back. Very much aware that he would need his rival’s assistance in realising his endeavour, Barbicane contacted Nicholl, who agreed to help. As construction of the spacecraft, and of the giant cannon needed to fire it, proceeded, Nicholl’s young assistant, Ben Sharpe, and Barbicane’s lovely daughter, Virginia, gradually fell in love.

On the day of the launch, Barbicane, Nicholl and Sharpe sealed themselves inside the spacecraft. Each man got inside a cylindrical chamber that soon filled with a special gas which reduced their heart rate to 5 beats per minute. The men did this in order to protect themselves from the extreme force, or G force, created when their spacecraft would be fired. The interlinked chambers began to spin like test tubes in a centrifuge as it shot out of the barrel of the cannon. Unknown to Sharpe, Nicholl and Barbicane, the latter’s daughter had snuck on board and concealed herself by putting on one of the spacesuits the men would wear on the Moon.

I don’t know about you, my reading friend, but I think that a digression would be a good idea right about now. When performing violent manoeuvres, a fighter or aerobatic pilot was / is / will be subjected to the aforementioned G force, which can cause a temporary loss of vision or even consciousness. Documented cases went as far back as the First World War but the introduction of new, high performance fighter aircraft during the 1930s exacerbated the risk to pilots. Such aircraft can be found in the amazing collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa. One only needs to mention the Hawker Hurricane, the Messerschmitt Bf / Me 109 and the Supermarine Spitfire, but back to our digression.

In Canada, before the start of the Second World War, Dr. Wilbur Rounding Franks, a cancer researcher at the Banting Institute of the University of Toronto, in Toronto, Ontario, began to work on a water-filled suit designed to help pilots remain fully conscious under strenuous combat conditions. Would you believe that he tested his basic idea with a laboratory centrifuge using mice immersed in water up to their neck inside preservatives? The mice survived.

Franks flight tested his anti-G suit in January 1940, in an airplane of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) – a brave move indeed and possibly his first flight in an airplane. A production model of the Franks suit was used in combat over North Africa in November 1942 by fighter squadrons of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm – a world first for this type of technology. Certain issues, among them security concerns and the lack of comfort during long missions, prevented further use of the Franks anti-G suit. No squadron of the RCAF ever used this device in action. Indeed, it proved to be a technological dead end, as air filled anti-G suits came to the fore. And no, my patriotic reading friend, the Franks suit was not the world’s first anti-G suit. If truth be told, German researchers had begun to look into the development of such devices no later than 1935. Their experiments indicated that a water-filled suit was not the way to go well before Franks completed his prototype.

Incidentally, a university lecturer and physiologist by the name of Frank Stanley Cotton developed an air-filled anti-G suit in Australia during the Second World War. Tested in November 1941, this device went into service with a Royal Australian Air Force fighter squadron in July 1943. The Cotton anti-G suit was not produced in large numbers. In Europe, from mid-1944 onward, many fighter pilots of the United States Army Air Forces wore G-2 air-filled anti-G suits in combat. As jet aircraft came to replace piston powered bomber and fighter aircraft after the end of the war, anti-G suits became indispensable, but back to our story. And yes, my grumpy patriotic reading friend, the story of the anti-G suit is an example of the nationalism that permeated / permeates the history of aviation. But back to our story.

As their spacecraft sailed though space, Barbicane, Nicholl and Sharpe met with a series of mechanical problems. And yes, my reading friend with a good memory, our Victorian astronaut friends were confronted by a meteor storm / shower – a common feature in space movies of the 1950s and 60s, and one mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, but back to the topic at hand.

Nicholl eventually admitted / revealed that he had purposefully damaged the spacecraft before liftoff. He feared that a successful journey to the Moon would lead to the adoption of Power X by many countries around the globe. Mankind’s innate nastiness would lead to a world war that could end all (human?) life on Earth. This strongly religious man even claimed he had acted with divine support. By organising a journey to the Moon, claimed Nicholl, Barbicane had flouted God’s commandments. Barbicane rejected this accusation. By making Power X available to many governments, he would ensure world peace.

Amid the chaos, Sharpe, Nicholl and Barbicane realised that the latter’s daughter was on board. They were profoundly shocked. Repair work on the spacecraft nonetheless proceeded as it sped through space. Uninvolved in these repairs, Virginia Barbicane assumed a domestic role. She cooked all meals, for example.

As the men began to contemplate the likelihood they would not survive the trip, the young woman reminded them all that humans were mortal. Indeed, she added, it would be a wonderful privilege to die in an awe inspiring explosion in space. Stunned by the calmness of his daughter, Barbicane stated that, if he was lucky enough to lead other journeys into space, he would insist that a woman be present in all cases – for courage.

Working side by side with Barbicane, Nicholl came to respect his rival / enemy, without abandoning his opinion about Power X. Better yet, he saved him from electrocution and possible death.

Unable to accept the likelihood that his beloved daughter would perish in space, Barbicane proposed a desperate solution. He would beak apart the spacecraft. Sharpe and his daughter would remain in the more comfortable main compartment, which was most likely to return to Earth. Nicholl and Barbicane, on the other hand, would complete the journey to the Moon in other compartments. Sharpe and Barbicane’s daughter protests’ were ignored. After helping Virginia and an unconscious Sharpe into their compartment, Barbicane broke up the spacecraft.

As Sharpe and Barbicane’s daughter approached Earth, they saw lights on the Moon. Nicholl and Barbicane, it seemed, had successfully landed. This realisation was tinted by sorrow as both knew that the 2 men only had limited supplies with them.

The next scene of the movie, the last one in fact, showed a man on Earth. This individual who had observed all that had gone on since the beginning picked up his bags and left for home where he would write a great novel about a journey to the Moon. This gentleman was, you guessed it, none other than Verne. The End.

And now for a few words, a great many words actually, from your local pontificator. Although filmed in Technicolor, From the Earth to the Moon was not a major production. And no, my concerned reading friend, this movie was not the main reason why RKO Pictures Incorporated, a subsidiary of General Tire and Rubber Company, ceased producing movies, in 1957, as a result of financial problems. Even so, this film studio was forced to sign an American distribution deal for From the Earth to the Moon with one of its rivals, Warner Brothers Pictures Incorporated. Neither studio spent a lot on money publicising the movie when it came out. RKO Pictures may not have been too proud of the final product and Warner Brothers Pictures may not have cared much about it.

By the way, did you know that the famous Warner brothers, perhaps born Wonsal or Wonskolaser, lived in Canada for a brief period of time, around 1890-92, and that one of them was actually born in London, Ontario? And yes, my witty reading friend, that was an example of the nationalism that permeated / permeates some of the film history works written and broadcasted around the globe. Sadly enough, Jack Warner, perhaps born Jacob Wonsal / Wonskolaser, may very well have been a sexual predator.

If yours truly may be permitted to digress for a moment, I would like to point out a potential inaccuracy on the Wikipedia page on From the Earth to the Moon. One could argue that this production was not the only film adaptation of the Verne novel of that same name. A Trip to the Moon came out in 1902. Directed by one of the great pioneers of cinema, France’s Marie Georges Jean Méliès, this movie was / is well worth seeing. Indeed, one can see parts of it at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, albeit on a fairly small screen, in its early aviation section.

Incidentally, Méliès also directed at least a couple of comedic films dealing with aviation, namely The Inventor Crazybrains and his Wonderful Airship and The Conquest of the Pole, premiered in 1906 and 1912. From the looks of it, both of these movies could still be watched as of 2018.

Let us now return to From the Earth to the Moon for some homebrewed pontificating. The movie’s director, although not well known today, could turn out well made movies. One only needs to consider the aforementioned War of the Worlds, as well as Treasure Island, The Naked Jungle and Conquest of Space, premiered in 1950, 1954 and 1955. Mind you, this gentleman also directed Robinson Crusoe on Mars, which had its premiere in 1964. Incidentally, the equally aforementioned Pal produced War of the Worlds, The Naked Jungle and Conquest of Space. In turn, the independent producer of From the Earth to the Moon is not well remembered today. An American journalist with a naughty sense of humour used his name, Benedict Bogeaus, to pen a somewhat cutting description of From the Earth to the Moon. The film, he said, was bogus Verne.

And the sad truth is / was that the film did not work all that well. Critics of the time slammed it, as did later ones. From the Earth to the Moon, they claimed, was stilted, serious, ponderous, pompous, glum, dull, cumbersome, clunky and chatty. The film did not attract a lot of viewers and was soon relegated to, dare we say it, the shame being so great, television.

The actors who played the main characters of From the Earth to the Moon certainly knew their trade but only the one who portrayed Barbicane seemed believable. All right, all right. The actor who played Nicholl was not too bad either. Many movie viewers of the late 1950s believed that Barbicane, a strong, smart and forceful individual, was the hero of the story. For them, Nicholl was a crazed villain. From his position as a 21st century individual, yours truly cannot quite agree with such an interpretation. While both men were certainly extremists, if not plain nuts, Barbicane’s stated opinion that the great powers of this world would refrain from war if they had access to Power X did not / does not feel all that convincing, or reassuring. If I may be so bold, mutually assured destruction may not be the best way to ensure the continuing existence of life on Earth. Given this, dare one say that Nicholl was an ambiguous hero who may have been saner than Barbicane? Indeed, it is possible that the film’s director and screenwriters felt the same way, but failed to put to point across.

Barbicane’s 1860s version of balance of power was an anachronism, one of the many that plagued From the Earth to the Moon. Most of the people who saw it in the late 1950s would have recognised Power X for what it was, a type of (thermo)nuclear weapon. One has to wonder why the director, producer and / or screenwriters introduced a 20th century technology in a 19th century storyline that included nothing of the sort. They seemingly did not feel that this century was cool enough. Dare one say that this decision illustrated the self-centred / self-absorbed nature of the United States in the 1950s? Many movie directors, producers and / or screenwriters of the time who worked on science fiction projects fell into this trap, and failed to make the leap in imagination that would have allowed them to leave Cold War fears behind and truly conquer the universe, and… You don’t believe me, now do you? The average American was not self-centred / self-absorbed in the 1950s, you say?

To make From the Earth to the Moon more relevant to a 1958 American audience, the movie’s director, producer and / or screenwriters added a female character to Verne’s all male cast, Nicholl’s lovely, defenceless and very brave daughter Virginia. What’s this, my reading friend? You find this addition amusing but think that Verne might not have been amused by said addition? You may very well be right but, as we both know, the team behind the aforementioned Journey to the Center of the Earth did the very same thing. The lady it added to the cast was as brave as can be – and rather pretty.

Mind you, some decades later, Sir Peter Robert Jackson and his team also chose to add a female character when they adapted John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s 1937 classic novel, The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, for the screen. As lovely as she was, Tauriel was anything but defenceless, however – a move made to make her more relevant to 21st century audiences. She took part in many of the most intense combat scenes of the second and third films of Jackson’s trilogy, namely The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, which hit the screen in 2013 and 2014. This being said (typed?), embroiling this lady elf in a love triangle did not feel quite right somehow, but then what do I know of elves and dwarves?

By the way, did you know that, back in 1995, Jackson and a friend, fellow director and producer Costa Botes, completed a documentary film? Forgotten Silver told the story of a forgotten filmmaking genius from New Zealand. If truth be told, Colin McKenzie was the greatest innovator in the history of cinema. Not only did this filmmaker invent the tracking shot and the close-up, albeit by accident, but he also produced sound and color movies many years before anyone else. The aviation enthusiast in you, yes, you, my reading friend, will be taken to seventh heaven, and back again, by a scene of one of McKenzie’s films. Using a computer to enhance the 90+ year old footage, Jackson and Botes were able to see a date on a newspaper. Said date proved that a forgotten aviation pioneer from New Zealand, Richard William Pearse, had performed the first controlled and sustained flight in a powered airplane in March 1903, 9 months before Orville and Wilbur Wright.

Did yours truly forget to mention that Forgotten Silver was a mockumentary film? I’m so sorry. Not. The sad truth was / is that McKenzie was a fictional character invented by Jackson and Botes. The 2 men seemingly allowed a journalist to publish a story which hinted that McKenzie’s was a real person before Forgotten Silver was broadcasted for the first time, on television, in October 1995. Many people were fooled, which led Jackson and Botes to point out that their film was a joke. Many people were amused by this revelation, but others were not. If truth be told, Forgotten Silver was / is a brilliant parody of a typical filmmaker biography. It also poked fun at the aforementioned nationalism that permeated / permeates some of the film history works written and broadcasted around the globe. Indeed, one could argue that nationalism permeated and continues to permeate many of the history works written and broadcasted around the globe, on topics as diverse as hockey and nuclear power.

A clarification if I may. Pearse was / is not a fictitious character. He was a farmer and inventor with some definite mechanical abilities. Pearse may have completed a powered airplane as early as 1901-02. He may have made several brief hops but proved unable to complete a single controlled and sustained flight. This being said (typed?), as you read these lines, there are people, mainly in New Zealand, who remain convinced that Pearse made at least 1 controlled and sustained flight before the Wright brothers. Others, mainly in the United States and / or Germany it seems, believe that a German American, Gustav Albin Whitehead, born Gustav Weißkopf, did the same thing in the United States in 1901 and / or 1902.

In Canada, a few people have put / are putting forward a similar claim on behalf of Louis “Lou” Gagnon, an individual mentioned in an October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Dare yours truly suggest that the aforementioned film history nationalism also permeated / permeates the history of aviation? You will remember, my reading friend, that the equally aforementioned October 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee poked fun, gently I hope, at the Canadian nationalism surrounding the first controlled and sustained flight of a powered airplane in what was then the British Empire.

Incidentally, Pearse should not be confused with Percy Winslow Pierce, one of the first members of the Junior Aero Club of America. This American teenager designed the Percy Pierce Flyer around 1909. Teenagers and adults interested in flying this very successful model airplane could acquire a kit or a set of plans. The kit remained in production for many years. You may be pleased to hear (read?) that the aforementioned aeroclub was co-founded by Emma Lillian Todd, one of the first women known to have designed an airplane. She shared this distinction with, no, not Canada’s Elizabeth Muriel Gregory “Elsie” MacGill. The young woman we are talking (writing?) about was British. This being said (typed?), Lilian Emily Bland married a distant cousin who lived in Canada, in British Columbia to be more precise, in 1911. She spent almost a quarter century here, or is it there, before returning to the United Kingdom in 1935. And yes, MacGill’s story is another example of the nationalism that permeated / permeates the history of aviation.

MacGill, who was from British Columbia incidentally, designed an airplane 25 or so years after Todd and Bland. She was the first woman in North America, if not the world to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, in 1929, in the United States. Designed to fulfill the needs of the Mexican air force, or Fuerza Aérea Mexicana, MacGill’s Canadian Car and Foundry Maple Leaf II elementary training airplane flew for the first time in October 1939, just after the start of the Second World War.

By then, MacGill’s employer, an important manufacturer of railway rolling stock named Canadian Car and Foundry Company Limited (CCF) had pretty much abandoned the idea of setting up a factory in Mexico. This being said (typed?), CCF again gave the idea some thought in 1940 before dropping it definitively. By then, the RCAF had indicated it saw no reason to order the Maple Leaf II. In October 1940, a small American aircraft maker acquired the production rights of the aircraft, as well as the prototype and 2 incomplete aircraft. Having failed to obtain a military contract, Columbia Aircraft Corporation sold everything it had bought to the Mexican government. The Fuerza Aérea Mexicana completed 12 or so Barreda Ares, a derivative of MacGill’s biplane, between 1940-41 and 1944. The Maple Leaf II thus became the very first Canadian designed aircraft to be produced by a foreign organisation. And here I go again, digressing as if there was no tomorrow. Sorry.

By the way, did you know that the acronym CCF also stood for Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the name of a Canadian socialist / social democratic party that gave birth to the no longer new New Democratic Party? Names of political parties can be funny that way. Some / many liberal, democratic or conservative parties may be anything but liberal, democratic or conservative, for example, but I digress. I also see the face of Big Brother turning this way.

Moving right along, at a fast pace, to evade the surveillance cameras, would you believe that Jackson was / is an aviation enthusiast just like you? Yes he is, and yes you are. Why else would you still be here, reading all this… stuff? Jackson’s movie production company was / is called WingNut Films Limited. Better yet, Jackson founded an aircraft restoration and manufacturing company, one of the best known and respected in the world, The Vintage Aviator Limited (TVAL). If truth be told, TVAL shipped 2 First World War era single seat fighter airplanes, a British one and a German one, to the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in late 2018. One of these is a Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a made in part from original components. The other is the museum’s very own Fokker D.VII, put together in New Zealand using a blend of original and modern components. The Assistant Curator, Aviation and Space, supervised that file in a masterful fashion. Way to go, EG!

You may be pleased to hear (read?) that the D. VII of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum is the only surviving aircraft of this type made by Junkers-Fokker Aktiengesellschaft, a company born of the 1917 gunshot wedding of the aeronautical division of Junkers und Company and of Fokker Flugzeugwerke Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung.

Would you believe that the museum’s D.VII was one of the aircraft acquired by a wealthy producer, pilot and businessman, Howard Robard Hughes, Junior, yes, that Howard Hughes, for the filming of Hell’s Angels? Premiered in 1930 as a sound movie, or talkie, this production was / is one of the great aviation movies of the 20th century. Yours truly would have been quite happy had the museum’s D.VII had been returned to the colours and markings it carried at the time of the filming – a heretical thought, I know, but it would have been so cool.

Incidentally, the Sopwith 7F.1 Snipe single seat fighter airplane presently owned by the Canada Aviation and Space Museum was also acquired by Hughes for the filming of Hell’s Angels, but back to our story. And yes, yours truly will refrain from pontificating about the S.E.5a, the D.VII or the Snipe. We are the Borg, sorry, we are the curator. Insistence is futile.

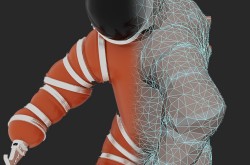

Where were we? Oh yes. Anachronisms. The flimsy looking spacesuits of From the Earth to the Moon did not look like the modified diving suits a 19th century engineer might have developed. They looked like the sort of thing a 1950s movie team with a limited budget would come up with. The elegant initials on each spacesuit were a nice touch, though.

As well, the interior of the spacecraft in which the main characters of our movie took place did not look like something designed in the 1860s. If truth be told, it bore more than a passing resemblance to the spacecraft one found in pulp magazines of the 1930s. What’s this, my reading friend? You do not know what a pulp magazine is – or was? Poor, poor little you. Sorry.

Pulps, as they were also called, were monthly publications, primarily American, printed on poor quality paper. They began their climb to greatness in the 1890s and remained popular until the 1950s. The breadth of topics covered by these unbelievably numerous publications was nothing short of breathtaking, from the profoundly pure and romantic to the very violent and warped. And yes, there were quite a few aviation pulps, and… We are moving away from the topic at hand, aren’t we?

Anachronisms, yes. Yes. With its glowing spirals, lighted sphere and spinning cylindrical chambers, the inside of the spacecraft in which the main characters of our movie took place looked like the inside of a pinball machine. The large rooms and step ladders were also quite unrealistic. As well, there was no way on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth that a gyroscope, even a big one, could counteract the microgravity of outer space.

What’s this, my reading friend? Too much negativity, you say? Negative, moi? Well, perhaps. On a positive note, one could argue that the plush interior of the spacecraft was quite beautiful and similar to other interiors seen in other Vernian movies of the late 1950s and early 1960s. One might even argue that the mechanical devices contained therein had a certain steampunk look. And yes, the term steampunk was mentioned in a February 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. And no, yours truly will not provide you with a painfully detailed definition of this fascinating word.

Yours truly would also like to point out that From the Earth to the Moon may not have been the movie the director, producer and / or screenwriters had in mind when they launched the project. The planned budget may, I repeat may, have been greater, for example. The original script may also have included more action. The final script may have become chattier when the required money failed to appear, as RKO Pictures’ fortunes took a turn for the worse. As well, the scriptwriters may have tried, without much success, to make their characters sound like 19th century people. They failed to capture the sense of wonder of that age. To be fair, the script held together pretty well until the launch of the spacecraft. From that point on, what promised to be the coolest part of the film went nowhere. No pun intended.

It has been suggested that the actors who played Barbicane and Nicholl were involved in the tweaking of the script. While the 2 men may actually have improved it, they may have done so at the expense of the younger actors who played Ben Sharpe and Virginia Barbicane.

Given the lack of money, any and all attempts made by the film crew to turn From the Earth to the Moon into a space epic fell flat. Given the anachronistic and flashy appearance of its spacecraft, you may be disappointed, or not, to hear (read?) that the design of the Earth based sets was rather pedestrian. If anything, the movie felt like a Western, and not an expensive one at that. The look and feel of the movie’s Earth based scenes might have been due to the fact that it was filmed in Mexico, near Ciudad de México – another money saving measure imposed on the crew. In turn, the relatively poor quality of the photography of From the Earth to the Moon might have been due to the fact that the Mexican film crew did not always fully understand what the American director wanted to achieve. Oddly enough, the harsh Mexican environment was not used to create a scene showing Barbicane and Nicholl on the Moon – an unforgiveable omission if I may say so.

The lack of money also affected the quality of the special effects of From the Earth to the Moon, which could be described as ineffective or dismal. The rod which supported the model of the spacecraft as it shot of the cannon, for example, was easily seen through the smoke and flames. Seeing the smoke trail left behind by this speeding vehicle rise slowly on screen was also pretty bad. And let’s not talk about the deep blue background seen on at least one occasion when the spacecraft was supposed to be in space. The Moon, when it came into view, was a poor quality painting.

Indeed, the very premise of the film was ludicrous. There was no way on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth that people fired out of a gigantic cannon could survive the titanic acceleration of the launch. The interlinked spinning cylindrical chambers that Barbicane, Nicholl and Sharpe got into would not have saved them. In any event, Victoria Barbicane survived the launch without the benefit of this cool looking device – a serious inconsistency in the plot if there was one.

The musical score of From the Earth to the Moon could best be described as unimaginative, if not trite. It is worth noting that some electronic sound effects, heard during the spaceflight, were lifted off the soundtrack of Forbidden Planet, one of the great science fiction movies of the 20th century. By the way, the somewhat bland captain of the spaceship of this 1956 movie was one Leslie William Nielsen. As we both know, this Canadian actor played a secondary character in Airplane, one of the great aviation comedies of all times. Nielsen’s performance in that 1980 motion picture did not go unnoticed. His movie career soon took off. No pun intended.

Where were we? Oh yes. For one reason or another, the director, producer and / or screenwriters of From the Earth to the Moon chose to eliminate one of the most interesting characters in Verne’s novel. Michel Ardan was a French adventurer whose last name was an anagram based on the nickname of a good friend of the author, Nadar, born Félix Tournachon. Would you believe that this very well known Parisian photographer, cartoonist and artist took the very first aerial photograph, from a tethered balloon floating above a village near Paris, in 1858? Vive la France – et les pommes de terre frites!

Better yet, in 1863, Nadar and 2 individuals from very different backgrounds formed the Société d’encouragement pour la locomotion aérienne au moyen d’appareils plus lourds que l’air – the world’s first organisation dedicated to the encouragement of aerial locomotion through heavier than flying machines. These men were Guillaume Joseph Gabriel de La Landelle, a journalist, author and officer in the French navy, the Marine impériale, a service known today as the Marine nationale, and Viscount Gustave Ponton d’Amécourt, a coin collector and amateur archaeologist. Would you believe that Verne and an even more famous French author, Victor Marie Hugo, were members of the Société d’encouragement pour la locomotion aérienne au moyen d’appareils plus lourds que l’air? So, vive la France – et les pommes… Sorry.

In 1862-63, de La Landelle and Ponton d’Amécourt supervised the fabrication of a miniature steam powered helicopter, which proved unable to take off. The gifted clockmaker who built this jewel did not realize that he was in all likelihood the first person to use a very rare and expensive metal, aluminum, to put together a heavier than air flying machine. Incidentally, it looks as if the de La Landelle / Ponton d’Amécourt helicopter has been preserved by the Paris-based Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, one of the great aerospace museums on this Earth. So, again, vive la France – et… Sorry.

Interestingly, an 1863 drawing of a hypothetical piloted flying ship by de La Landelle inspired at least in part the design of the Albatross, an electrically-powered flying ship found in Clipper of the Clouds. Would you believe that the plot of this science fiction novel published in French by Verne in 1886 included a flight from Québec, Québec, to Ottawa, by way of Montréal, Québec, that lasted 3 and a half hours? Its average speed of about 115 kilometres / hour (about 70 miles / hour) was barely higher than that of the trucks, motorcycles, cars and buses traveling by road in 2018 – when there is no construction work that is, and that’s no joke, as we both know.

You may be pleased to hear (read?), or not, your choice, that Ponton d’Amécourt invented the word hélicoptère in 1861-62. De La Landelle, on the other hand, invented the word aviation in 1863. So, yet again, vive… Sorry. Sorry.

That is all. For now.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)