“Two petroleum steak tartare for table 13, and move yourselves, god dang it!:” The great adventure of a manna which briefly had the wind in its sails, single-cell proteins grown on petroleum derivatives, Part 2

Hello, my reading friend! How are you doing? […] Good, good.

I dare to hope that you are able to continue our examination of the history of single-cell proteins grown on petroleum derivatives. […] Good, good.

Having obtained the green light from the management of the British petroleum giant British Petroleum Company Limited, the spiritual father of that adventure, the research director of its French subsidiary, the Société française des pétroles BP, the French mechanical engineer / chemist Alfred Champagnat, got to work.

He and his team first isolated yeasts which fed on hydrocarbons. Said yeasts were subsequently cultivated. The final product of the team’s work was a powder which contained up to 40%, if not 60% protein and…

Fear not, my reader friend with a delicate stomach, those proteins were intended for animal feed. Mind you, those animals would later be transformed into biftecks, breasts, cutlets, escalopes, gigots, hams, haunches, jambons, poitrines, roasts, rôtis, scallopinis, schnitzels, steaks, etc. Bon appétit tout le monde!

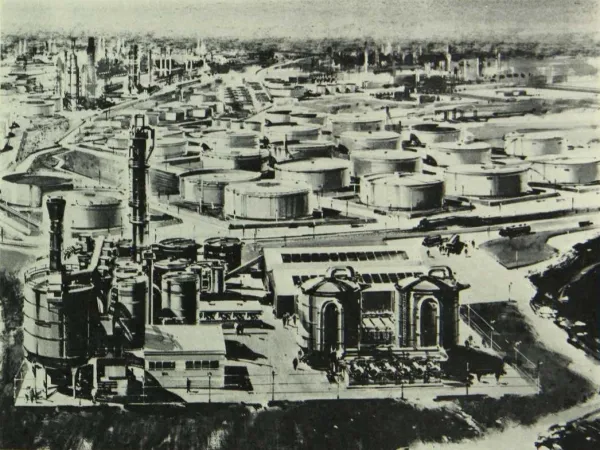

Incidentally, the first newspaper articles concerning Champagnat’s work appeared no later than December 1962. Other texts, published from 1963 onwards, mentioned the Lavéra pilot plant, located very close to the petroleum refinery of the same name, in Martigues, France, not far from Marseille.

Would you believe that there was, in the reception office of that refinery, a series of sample bottles containing products from the Société française des pétroles BP? Right next to a bottle with a label with the words “Gaz Oil Lourd” was another with the word “Bifteck.” And yes, said bottle contained protein powder. Someone in the firm, it seemed, had a sense of humour.

Incidentally, Champagnat’s work was mentioned, without mentioning his name or that of the Société française des pétroles BP however, at least not in the press, at the VIII International Congress for Microbiology, held in Montréal, Québec, in August 1962. That information might, I repeat might, have emanated from John C. Sylvester, the rather enthusiastic director of microbiological research at an American medical devices and healthcare firm, Abbott Laboratories Incorporated.

And no, yours truly cannot say if Champagnat was present at the 1962 congress. He did not present a communication, that much was sure, but he might indeed have been there. Maybe.

In 1965, British Petroleum commissioned a pilot plant at Grangemouth, Scotland, located very close to an existing petroleum refinery, which could produce 4 050 or so metric tonnes (4 000 or so imperial tons / 4 500 or so American tons) of single-cell proteins (SCP) made from petroleum per year. It used paraffins as a base product.

It should be noted that the staff at the BP Research Center in Sunbury-on-Thames, England, a suburb of London, were also involved in protein research.

Would you like to hear Champagnat talk, in French of course, about his work, in 1967? Wunderbar!

Incidentally, Champagnat and 2 colleagues shared, in 1968, the Prix du Cinquantenaire of the Société de chimie industrielle, a French learned society founded around May 1917. Champagnat seemingly retired that very year.

Would you believe that, no later than November 1968, a patisserie in Martigues offered biscuits made partly with synthetic proteins? I kid you not. A team from the French state radio and television broadcaster, the Office de radiodiffusion-télévision française, having visited it then, Chez Titin and its owner became known throughout France.

“It seems that the Japanese are preparing petroleum steaks,” stated a lady journalist, jokingly, words translated here. “Well, us, we will provide dessert!” replied Titin without missing a beat.

Would you like to see a video, in French of course, my reading friend? Wunderbar!

In 1970, I think, the Société française des pétroles BP or, more precisely, the Société de développement des protéines, inaugurated at Cap Lavéra the world’s first commercial factory producing SCPs made from petroleum. That facility could produce 16 000 or so metric tonnes (15 750 or so imperial tons / 17 650 or so American tons) of SCPs per year. Those SCPs produced from paraffins were known as Toprina.

British Petroleum founded a new subsidiary, the British firm BP Proteins Limited, in 1970, to market its SCPs.

Yours truly will use the acronym SCP from now on, without the words made from petroleum, if you do not mind.

Thank you.

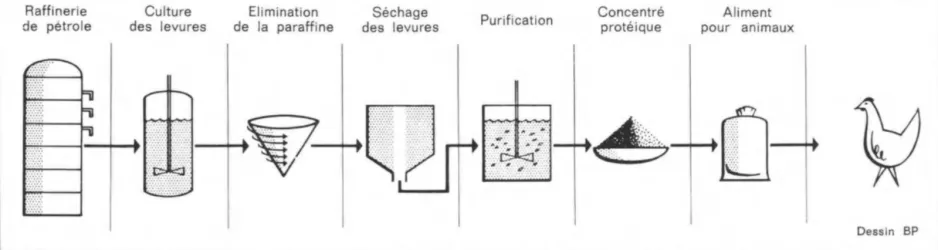

And here is a diagram which showed how SCPs were produced at the Cap Lavéra factory…

A diagram which shows how proteins were produced from petroleum at the Cap Lavéra factory. Alexandre Nesmeyanov and Vassili Belikov, “Cuisine synthétique trois étoiles.” Le Courier, March 1969, 22.

As you might imagine, SCPs quite quickly received another, much more impactful name which deeply irritated the French-speaking researchers and their bosses. Un bon petit steak de pétrole, monsieur?

It was apparently in 1971 and 1972 that the French and Scottish pilot plants began to produce SCPs in a semi-commercial manner.

The progress made by BP Proteins engineers was such that it received the prestigious Kirkpatrick Chemical Engineering Achievement Award in 1973, an award presented every two years by the American monthly magazine Chemical Engineering. BP Proteins was the first foreign company to win that prize.

A plant capable of producing 100 000 or so metric tonnes (100 000 or so imperial tons / 110 000 or so American tons) of SCPs per year was completed in early 1976, at Sarroch / Sarrocu, Italy, not far from Cagliari / Casteddu, on the island of Sardinia. This was a project approved in 1972 which united British Petroleum and an Italian national company, Azienda Nazionale Idrogenazione Combustibili Società per azioni, which happened to be a subsidiary of an Italian industrial giant, the public economic body Ente Nazionale Hydrocarbon Società per azioni.

The Italian firm Italproteine Società per azioni was then created in order to manage that factory which, as envisioned in 1972, would be the largest in the world. Said factory used the production process developed at Grangemouth, by the way.

Was British Petroleum the only petroleum company investing in petroleum-derived proteins, you ask, my reading friend? Of course not. Most of the major American petroleum companies (Gulf Oil Corporation, Socony Mobil Oil Company, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey and Sun Oil Company) embarked on the adventure even before the end of the 1960s.

The same went for many large Japanese chemical firms. Three or four pilot plants thus came into existence in that country. Another pilot plant, owned by a government entity, opened in Taiwan. A commercial factory which had nothing to do with British Petroleum also opened its doors in Italy, in 1974.

Indeed, would you believe that interest from at least one major American petroleum company, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, dated back no later than 1962? Yes, yes, 1962. Articles published in January 1963 in American daily newspapers mentioned the pilot plant of the American firm Esso Research and Engineering Company, a subsidiary of Humble Oil and Refining Company, itself a subsidiary of… Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

And yes, yours truly also wonders if the publication of the first newspaper articles on Champagnat’s work, in December 1962, inspired the publication of the articles on the work done by Esso Research and Engineering.

Interestingly, the Swiss multinational food and beverage processing conglomerate Nestlé Alimentana Société Anonyme participated in the work of Esso Research and Engineering for a time in the mid-1960s.

In the early 1970s, the American multinational food giant General Mills Incorporated joined forces with the American petroleum firm Phillips Petroleum Company to form Provesta Corporation, a firm which soon began research.

Even Soviet bloc countries got into the act. Romania, Czechoslovakia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) had projects in progress.

Indeed, the Soviet government oversaw the commissioning of two pilot plants, in 1964 and 1968. Better yet, no fewer than 9 commercial factories with a total production capacity of 1 425 000 or so metric tonnes (1 400 000 or so imperial tons / 1 575 000 or so American tons) of SCPs per year entered service between the late 1960s and the 1980s. Wah!

Given the enormous losses of agricultural products due to waste that the USSR had to deal with at that time, the production of those factories constituted an important complement to national protein production.

And yes, the Soviet synthetic protein production program was by far the largest in the world.

As you might imagine, analysts from the Central Intelligence Agency, an American intelligence agency mentioned many times in our magnificent blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since February 2018, followed the evolution of that program as best they could.

All of those synthetic protein production projects owed much to the fact that many prominent members of the global scientific community strongly supported the development of that technology.

In November 1974, the director and general manager of BP Proteins and president of the European Association of Single Cell Protein Producers, Hector Watts, claimed that the countries of the European Economic Community could produce 500 to 600 000 or so metric tonnes (500 to 600 000 or so imperial tons / 560 to 575 000 or so American tons) of synthetic proteins in 1980.

You have a question, do you not, my patriotic reader friend? Was there a plan for a factory in Canada, you ask? A good question. The answer was yes. Discussions between the government of Alberta and an unidentified firm were in fact underway as 1973 ended. The commercial plant in question would be the first in North America and… you have another question.

Were the proteins produced according to the process put forward by BP Proteins dangerous, you ask, my reading friend concerned about her / his diet? Another good question.

Two research institutes of the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek, in other words the Netherland organisation for applied research in natural sciences, concluded in the first half of the 1970s that those proteins, very nutritious proteins by the way, were completely devoid of harmful or toxic effects.

British Petroleum might, I repeat might, have also obtained the blessing of the United States Food and Drug Administration and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Studies were carried out on (Dutch? British?) sites that yours truly has not been able to identify, with pigs, lambs, chickens and calves, as well as with rainbow trouts. Those demonstrated, it was said, that Toprina could be included without negative impact in the diet of those animals.

In addition, an unprecedented program studied more than 50 000 rats and Japanese quails over 20 or so and 30 or so generations. Once again, it was said, the researchers did not detect a negative impact.

Several European countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Netherlands, United Kingdom and West Germany) apparently approved the introduction of Toprina into animal feed no later than 1973.

Indeed, the sale of Toprina as a milk substitute in calf feed and as a fishmeal and soymeal substitute in pig and poultry feed began in 1971 in the United Kingdom and in 1972 in France.

SCPs had, it seemed, the wind in their sails. Some people already imagined the end of world hunger.

Let us not forget, a steer weighing 450 or so kilogrammes (1 000 or so pounds) produced 450 or so grammes (1 pound) of protein per day, according to Champagnat. The same mass of yeast could produce 1 125 or so kilogrammes (2 500 or so pounds) of protein in that same period of time. Wah!

In addition, it took more than 27 000 litres (6 000 or so imperial gallons / 7 200 or so American gallons) of water to produce the same 450 or so grammes (1 pound) of beef protein. Re-wah!

Given an annual global animal protein deficit of 3 or so million metric tonnes (3 or so million Imperial tons / 3.3 or so million American tons), stated Champagnat, 1 or so percent of the world’s annual production of paraffinic crude oil would suffice to fill it.

This being said (typed?), the World Health Organization’s Protein Advisory Group expressed concern in 1973 that batches of petroleum-based proteins might not be the same. Their differences thus cast doubt on the validity of manufacturers’ assurances based on a particular set of tests.

The oil crisis which exploded on the world scene in October 1973 changed the situation, everywhere and for everyone.

In reaction to the support given to Israel by the United States during the Yom Kippur War / Ramadan War / October War / 1973 Arab–Israeli War / Fourth Arab–Israeli War, in October 1973, the Munazamat al’Aqtar Alearabiat Almusadirat Lilbitrul, in other words, the organisation of Arab petroleum exporting countries, reduced its production by 5 %. Worse still, it intended to reduce its production by 5 % per month as long as the Tsva ha-Haganah le-Israel, in other words the Israeli armed forces, did not evacuate all of the Arab territories occupied during the Six Day War of June 1967.

The organisation of Arab petroleum exporting countries also imposed an embargo against the United States and other countries which supported Israel, but not really against Canada. In the United States, millions of motorists flocked to gas stations. Many of those soon found themselves dry. All over the country, there was panic.

The administration headed by Richard Milhous “Tricky Dick” Nixon was so shocked by what was happening that it briefly considered seizing by force the oil fields of countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, etc. I kid you not.

Let us not forget that, in October 1973, Nixon was mired up to his neck in the Watergate scandal. One wonders how the United States Congress and the people of the United States would have reacted to the news of attacks launched against Arab countries hitherto friendly to the United States by a president who deserved to be impeached. One also wonders how the United Nations Organization and the international community would have reacted.

In any event, the embargo of the Arab petroleum exporting countries was not lifted until March 1974. It was lifted despite the fact that the Palestinian populations of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem were still under the yoke of the Israeli occupation troops.

Fifty years later, in 2024, those same populations were still living in territories under Israeli occupation, and we all know what has been happening in the Gaza Strip since October 2023 (more than 32 500 fatalities, including more than 12 500 children).

If I may be permitted to quote once again, out of context, a sentence taken from the great novel Allah is not obliged, published in French in 2000 by the great Ivorian writer and athlete Ahmadou Kourouma, there is no justice on this Earth for the poor.

In any event, the Société française des pétroles BP and / or its parent company, the British petroleum giant British Petroleum, closed the Cap Lavéra SCP factory in Martigues in 1975. That closure was due to various factors: various technical problems, the high price of oil, and the relatively low prices of soybeans and fish meal.

The factory was quickly razed, perhaps as early as 1976.

Also in 1975, before or after the aforementioned closure, the Italian Istituto Superiore di Sanità noted the presence of certain unusual chemical compounds in the meat and fat of animals fed with the Toprina produced by the aforementioned Sarroch factory. In the interest of prudence, while waiting for other studies to be completed, the Ministero della Salute obtained the suspension of the decree which had allowed the construction of the factory. The Sarroch factory thus shut down in February 1976 an experimental production run which had begun the previous year.

Citizen groups were formed to prevent the introduction of proteins produced from petroleum into animal feed. Major Italian soybean producers might have encouraged those actions to thwart the arrival on the scene of a potentially dangerous competitor.

The requested studies having demonstrated the presence of certain unusual chemical compounds in the meat and fat of animals fed with Toprina, Italproteine and British Petroleum emphasised that those compounds were present in nature.

In October 1976, the Italian authorities authorised the production of Toprina for experimental purposes but without that product being put on sale. The factory produced several hundred metric (imperial / American) tonnes of Toprina between December 1976 and April 1977. Alarmed by the atmospheric emissions from the factory, those same authorities then revoked their authorisation.

Mind you, the Italian authorities then had to take into account a petition signed by thousands of residents of the Sarroch region according to which the factory was a danger to them, as well as to the factory staff.

Realising the extent of the fears caused by atmospheric emissions from the plant, the management of British Petroleum stated it was ready to install a device which would reduce them. The mayor of Sarroch, however, refused to grant a construction permit as long as said discharges were deemed harmful. Municipal elections having to take place in February 1978, that magistrate could not ignore the fears of the population.

The Istituto Superiore di Sanità, for its part, required that the discharge reduction device be able to incinerate them in order to eliminate any emission of live yeast.

For British Petroleum, the scale of those demands compromised the future of the factory. Indeed, they could deal it a fatal blow.

In September 1977, British Petroleum and its partner, Azienda Nazionale Idrogenazione Combustibili Società per azioni, agreed to liquidate Italproteine if all the permissions the plant needed to operate were not in place by January 1978.

A strategic review of BP Proteins completed in November 1977 went even further. If the permissions the plant needed were not in place before the Sarroch plant (commercially?) came online in mid-1978, British Petroleum would have to stop all work related to synthetic proteins. Given the economic situation and oil prices, large-scale adoption of petroleum-derived synthetic protein technology was unlikely.

A meeting of the Consiglio superiore di sanità, in November 1977, only resulted in the creation of a committee which would try to see clearly in the two projects for the production of SCPs in Italy, in Sarroch and in Montebello Jonico, not far from Reggio Calabria, in the south of the country.

That second factory, owned by Liquichimica Biosintesi Società per azioni, had in fact only operated for a short time, 2 months perhaps, around 1974, before the Italian government ordered the cessation of production, deemed very / too polluting. Worse still, the proteins it was to produce, using a process of Japanese origin, proteins marketed under the name Liquipron, contained a product deemed carcinogenic.

The aforementioned committee did not meet as planned in January 1978. It would do so only in February.

At the beginning of February, even before that committee met, the management of British Petroleum decided to liquidate Italproteine. The latter’s board of directors ratified that decision at the end of the month.

The Sarroch factory closed its doors in April 1978, without having sold a single protein.

That closure was all the more embarrassing since the Italian government had to ignore a ruling from the European Economic Community to allow the factory to open its doors in 1976. Said decree in fact mentioned that the factory constituted a danger of pollution and that the proteins produced were not sufficiently proven to be produced commercially.

British Petroleum shut down its Grangemouth pilot plant in July 1978. A great dream was coming to an end.

A factory project in Venezuela involving the state company Petróleos de Venezuela Sociedad anónima and British Petroleum, a mere minority partner (20%), had been shelved in 1977. Another project involving the Saudi state company Sharikat Bitrumin did not go beyond the project stage either. Another project, this time involving the Soviet government, also failed.

And yes, yours truly is also a little perplexed. Why on Earth did the British government allow British Petroleum to help the ideological enemy that the USSR was feed its population?

Rumours that American soybean producers pressured the administration led by President Gerald Rudolph Ford, Junior, to get British Petroleum to abandon its plans to produce synthetic proteins obviously cannot be confirmed.

What was a little sad about all this was that, in November 1976, Champagnat had won the prestigious UNESCO Science Prize, UNESCO being the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “for his findings on the low-cost mass production of new proteins from petroleum.” He received the prize in question, awarded every two years, in December from the General Director of said organisation, the Senegalese politician Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow.

Given that the prize in question included a sum of US $ $3 000, a sum which corresponds to about $ 21 800 in 2024 Canadian currency, it begged the question whether Champagnat had to give that moolah to his former employer.

By the way, the UNESCO Science Prize recognises individuals or groups who contribute in an exceptional way to the development of the teaching of scientific and technical research, or to industrial technological progress.

In 1970, Champagnat had received the Prix Nessim-Habif awarded annually by the Société des ingénieurs Arts et Métiers, the association of former students of one of the oldest engineering schools in France, the École nationale supérieure d’arts et métiers of Paris.

Mind you, Champagnat was also awarded the Redwood Medal of the England-based Institute of Petroleum in 1971. That medal rewarded petroleum technologists of outstanding eminence of any nationality.

In 1973, the England-based Society of Engineers had awarded him the very first Gairn EEC Gold Medal, a biannual award created to reward exceptional scientific and technological achievements in the European Economic Community.

As impressive as those awards were, one could argue that they amounted to little given the failure of the SCP adventure.

I do not have to tell you that the Alberta plant project went nowhere.

The saga of the Cap Lavéra protein factory inspired the French actor / author / playwright Bernard Avron. In 1984, that father of the Théâtre et Sciences concept and of the PEPAC Théâtre, Sciences et Entreprises, wrote Les bio-protéines de M. et Mme Dutraillon, a play in which, in translation, “A domestic computer ponders the future of biotechnologies, under the complicit eye of three-dimensional television.”

And thus ends this edition of our you know what. See ya.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)