In 1902, was the secret of steering dirigible balloons held by Quebecer Louis N. Filion? That is for me to know and you to find out

Oyez, oyez, oyez, my reading friend, yours truly has the infinite pleasure of presenting to you another edition of our fabulicious blog / bulletin / thingee.

I will confer with you today about a question which had haunted your mind night and day for like, forever: how can one steer an airship / dirigible in the vertical plane, in other words in pitch?

In 1902, shortly after the 20th century had begun, in 1901 of course, a modeler, sculptor, stonemason or worker living in Montréal, Québec, believed he had found the solution to that thorny problem. Louis N. Filion had been digging into / toiling on that issue for a few / several years in fact, it was said (typed?). He had actually invested the bulk of his savings there. One wonders what his spouse since 1896, Anna Filion, born Jean, thought of it.

Filion may, I repeat may, have begun construction of his airship around the beginning of 1902, or even in 1901. If we are to believe the articles which appeared from June 1902 onward in several Québec newspapers and magazines, a good third of the construction work on that flying machine was complete. However, the inventor did not have the financial means to complete his work.

Filion confided to journalists, as early as June 1902, that he would gladly agree to bind himself to a partner with deep pockets. That person’s money would allow him to get his hands on the many sheets of aluminum he needed to cover the hull of his flying machine. If such a patron showed up quickly, Filion seemed to hope he could take to the air before the end of the autumn of 1902.

Filion ultimately had to give up flying that year. This being said (typed?), he confounded some doubting Thomases by organising a demonstration in a partially flooded Montréal quarry, at the end of October 1902. Some people having indeed expressed the opinion that the airship’s rudder, placed just behind the propeller, would not be very effective, Filion mounted a manually operated aerial propeller and an equally aerial rudder on a very ordinary boat. Despite a headwind and rain, the inventor managed to control his craft. Indeed, he moved forward and backward, and turned as if nothing was the matter, a performance reported by a journalist from the important Montréal daily La Presse.

The Filion airship was indeed innovative to say the least. Its hull consisted of a series of wooden rings and (wooden?) beams forming a cylindrical structure capped by two cone shaped (wooden?) structures, fore and aft, structures similar in appearance to bicycle wheels if seen from the front. All that assembly, covered with thin aluminum sheets, gave great rigidity to the airship. At least, that was what Filion said.

A good coat of white lead, a highly toxic product, theoretically sealed the hull of the Filion airship and reduced gas leaks to a minimum. Theoretically.

A valve placed on the left side of the hull allowed the gas which would maintain the airship in the air, hydrogen in that case, to escape if the internal pressure became too high.

The pilot of the aerostat would occupy a small gondola suspended under the hull by thin steel cables.

The propeller of Filion’s flying machine was activated by a chainless pedal and gear mechanism somewhat similar to that of some bicycles.

Yours truly must confess being intrigued by a slight resemblance between the Filion airship and the Schwarz airship, designed by a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a timber merchant in fact, David Schwarz / Schwarz Dávid, and… What is it, my easily troubled reading friend? Do you not know that, in the Hungarian part of said empire, a person’s first name followed / follows their surname? Sigh… Let us move on.

The front part of the Schwarz rigid airship, the first such flying machine on the planet we share, did indeed have a conical shape. The rear part, on the other hand, was almost flat. It actually was very slightly rounded. These two parts were joined by a third, cylindrical in shape. Both the internal structure and outer covering of the airship were made of aluminium. Power was provided by a gasoline engine.

A first example, built around 1893 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, seemingly did not fly.

A second example, about 48 metres (about 157 feet) long, made a brief flight near Berlin, German Empire, in November 1897. Problems with the transmission belts of the pair of propellers which ensured the propulsion of the machine forced the young military pilot, who obviously had no piloting experience, to land urgently, with success. The airship, however, overturned in the moments that followed. The damage it suffered was irreparable.

Schwarz was spared that terrible vision, however. He had died in January 1897, at the age of 46.

While the flight of November 1897 was certainly mentioned in the European aeronautical press of the time, very few Québec dailies published more than a word about it. As a result, it is difficult to assess the chances that Filion had heard of it.

This being said (typed?), Filion claimed to be familiar with the experiences of a retired German officer mentioned several times since December 2017 in our excellent blog / bulletin / thingee, Count Ferdinand Adolf August Heinrich von Zeppelin, and of a rich and fearless Brazilian mentioned several times in that same publication since November 2018, Alberto Santos Dumont.

And yes, the lifting gas of the Filion airship, hydrogen you will remember, seemed to occupy all the interior space of its hull, just as was the case, it seems, for the 2 examples of the Schwarz airship.

Why not use helium, you say (type?), my slightly troubled reading friend? That gas was / is not flammable, after all. A good point. Please note, however, that helium was not available in industrial quantities in 1902. Indeed, it was not until 1903 that a source other than a chemical laboratory made its appearance. That year, American researchers discovered helium in a sample taken from an oil drilling site in Kansas, in the United States. And still, the quantities produced were apparently not huge. Indeed, it was not until December 1921 that an airship, the United States Navy’s C-7 non-rigid airship to be more precise, took to the air using helium for the first time.

But back to the airship of Filion. Its great innovation, according to the latter, lied elsewhere. And yes, my reading friend, it did indeed relate to the control system. Aware of the need to maintain the balance of his flying machine in the vertical plane, in other words in pitch, throughout flight, Filion used a mobile mass, sliding along a cable placed under the nacelle of the airship. That approach was, according to the inventor, more effective and much less heavy than the use of engines equipped with horizontal propellers. It also eliminated the need to transport sand or water as ballast, which increased the payload of the machine accordingly.

The pilot could obviously move the mobile mass as he or she pleased. He or she also activated the fabric-covered rudder placed aft of the propeller, an arrangement which increased its efficiency.

And yes, my reading friend whose erudition often leaves me speechless, you are quite right. A German engineer, Theodor Kober, used a moving mass to maintain the balance of his first flying machine in the vertical plane, in other words in pitch. And yes, he did so before Filion.

Said machine was the LZ 1, or Luftschiff Zeppelin 1, a flying machine was far more complex than that of the Filion airship. The hydrogen which kept the LZ 1 aloft was also inside 17 rubberised cotton cells. And no, the skin of the hull of that behemoth (about 128 metres (about 420 feet)!) was not aluminum. It was in fact made of cotton.

The first flight of the LZ 1, in July 1900, unfortunately ended with an emergency landing caused by a blockage of the mobile mass, the failure of one of the 4 engines and a breeze which was a tad too strong. It flew again in October 1900, but that is another story. Yes, yes, a story other.

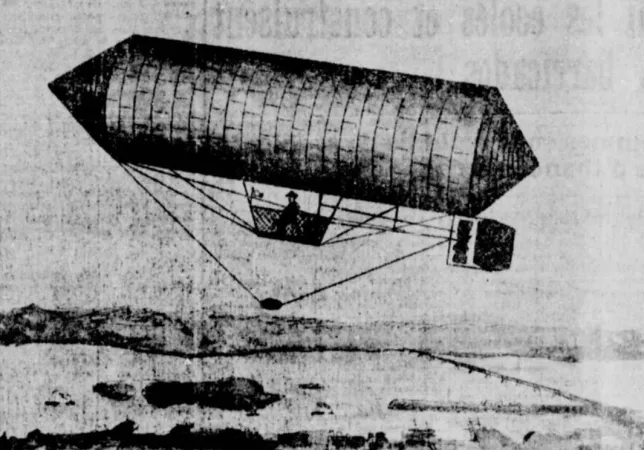

Louis N. Filion. Anon., “Un grand projet.” Album universel, 28 June 1902, 194.

Who was the modeler, sculptor, stonemason or worker, well forgotten in 2022, who designed the Montréal airship at the heart of this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee?

Filion was born in August 1871, in La Malbaie, Québec – a village located on the north shore of the majestic St. Lawrence River.

Yours truly must confess to having found very little about Filion’s life. Before embarking fully on the design and manufacture of his aerostat, he worked for a well-known monumental mason from Lévis, Québec, Olivier Jacques, and that is it.

Given these circumstances, may I suggest that this peroration limits itself to Filion’s aerostatic activities?

Many thanks.

A few citizens of Montréal were so intrigued by Filion’s project that they agreed to create a small limited company, apparently in 1903. The funds invested by these patrons, no more than $ 2 000 or $3 000 it was said, or about $ 54 000 or $ 81 000 in 2022 currency, made the purchase of the aforementioned aluminum sheets possible. Filion and a small team worked hard for many months to complete the airship.

An article published a little before mid-August 1903 in the important Montréal daily La Patrie pointed out that Filion planned to make a first test flight even before the end of that month.

Better still, Le Canada informed its readership that the airship of Filion, the Canadian Santos-Dumont according to that Montréal daily of secondary importance, was to be one of the attractions of the agricultural and industrial exhibition to be held in Saint-Jean, Québec, today’s Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, from 5 to 12 September.

Better squared, an American daily newspaper, Boston Evening Transcript of… Boston, Massachusetts, reported before the end of August 1903 that Filion was to be among the people scheduled to participate in the imposing triennial exhibition organised by the Merchants and Manufacturers’ Association of Boston, an exhibition which took place from 5 to 31 October.

And no, my slightly overenthusiastic reading friend, Filion and his machine were not, in the end, among the attractions of the Saint-Jean exhibition. The inventor did not seem to go to Boston either. It makes one wonder if Filion was not showing a tad too much enthusiasm in his declarations.

More than 20 000 (!) tiny screws or rivets later, on 25 July 1904, in the early evening, Filion demonstrated his airship.

The aerostat completed by Filion and his team could finally be examined quite closely, but not too closely however. It was about 17 metres (about 55 or 56 feet) long and weighed about 90 kilogrammes (about 200 pounds), it was said – a figure which may not really have reflected reality if I may comment. Indeed, a contemporary source suggested that the aluminum sheets which covered the structure of the airship alone weighed more than 90 kilogrammes (over 200 pounds).

Anyway, the hull of said airship being able to contain about 240 cubic metres (about 8 500 cubic feet) of a gas lighter than air, hydrogen, it could lift a payload of about 170-180 kilogrammes (about 375-400 pounds), assuming of course that its structure would tip the scales at about 90 kilogrammes (about 200 pounds), a number which, as I just said (typed?), seemed to me a tad suspicious. Anyway, let us move on.

The Filion airship was the first and, quite possibly, the only / last rigid airship designed and / or manufactured on Québec or Canadian soil. Filion himself may have been the third person / team on planet Earth to design and build a rigid airship.

Would you believe that Filion oversaw the fabrication of the equipment which produced the hydrogen for his airship? Said equipment used iron filings and hydrochloric or sulfuric acid, two products which were / are extremely dangerous to health, to produce the gas in question. It goes without saying that Filion oversaw the production of the hydrogen he needed.

Did you know that the hydrogen, or flammable air to use a terminology of the time, produced in August 1783, in Paris, France, under the supervision of French physicist / inventor / chemist Jacques Alexandre César Charles, was produced in the same way?

Why did Charles need that gas, you ask? To fly the first gas balloon made on planet Earth, by Jove. Said balloon, a 4 or so metre (13 or so feet) diameter beach ball, was fabricated by 2 well-known makers of measuring devices, the brothers Anne-Jean Robert and Nicolas-Louis Robert, alias Marie-Noël Robert. The multicoloured sphere traveled a distance of about 16 kilometres (10 miles) before landing near Gonesse, France. The population of the place, which had never seen anything like it, did not take long to attack with pitchforks and stones that unknown object whose sulphurous smell portended the worst.

Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert took to the air aboard a larger gas balloon in December 1783. That first piloted flight aboard a gas balloon, the second piloted flight in a balloon on this Earth, unfolded without a hitch. Charles and Robert landed about 35 kilometres (about 22 miles) from Paris, near Nesles-la-Vallée, France. Charles quickly took off alone and reached an altitude of about 3 300 metres (about 10 800 feet). Yes, yes, about 3 300 metres (about 10 800 feet). That Charles was much braver than yours truly. Frozen to the bone, he alighted nearby and without incident.

I sincerely apologise for this aerostatic digression, my reading friend. I really like balloons, but back to the Filion airship.

For the purposes of the July 1904 demonstration, the hull of said airship was only partially filled (67 %?). That inflation was most likely made where the demonstration was taking place, a vast field behind the field of the well-known Shamrock Lacrosse Club of Montréal.

While it was true that Filion and his associates wanted to fly without witnesses, the fact was that at least one person could not shut up. Indeed, about 200 people showed up to attend the event. Oh joy.

An unfortunately unidentified young man having boarded the airship, reported La Presse, the people who kept it on the ground with cables dropped everything. The imposing flying machine rose majestically. The young aeronaut, who obviously had no piloting experience, did very well. The airship responded all in all well, a response most likely caused by an absence of wind.

That was the first airship flight on Québec, or even Canadian soil.

This being said (typed?), the absence of an engine abord Filion’s machine meant that it was not really a practical flying machine. Given that, one could argue that the first controlled and sustained flight of a practical lighter than air flying machine on Québec, or even Canadian soil, took place in Montréal on 13 July 1906. The previous day, Charles Keeney Hamilton, an American aeronaut and former fairground balloonist and parachutist, had to land moments after taking off when some of the cables which linked the envelope of his small non rigid airship to its nacelle began to snap. He and the maker of the airship, Augustus Roy Knabenshue, who had rushed from New York City, New York, by train, worked for hours to repair it.

And yes, you are quite correct, my reading friend. Several / many Knabenshue airships flew in North America between 1905, when the first one was tested, and the onset of the First World War, in 1914, but back to the first flight of the Filion airship.

The young man at the helm having landed safely, Filion took his place and left the ground. Both the inventor and the witnesses present soon realised, however, that the higher weight of Filion severely limited the performance of the airship. The inventor nonetheless also landed without incident, to the applause of the small crowd.

And yes, my reading friend, yours truly presumes that the landing made by the unidentified young man was also made to the applause of the small crowd. It would only have been fair.

It should be noted that the description of what happened on 25 July 1904 published in La Patrie differed from that which appeared in La Presse. The journalist Omer Chaput indeed affirmed, on the front page, note it well, that he carried out 3 short flights at very low altitude, less than 20 metres (approximately 60 feet) in fact, aboard the Filion airship. The aerostat was held by ropes to prevent it from going too high or too far. According to Chaput, the presence of these impediments was due to the fact that the Filion airship then had no device to control its ascent and descent. One of two things, either the aforementioned mobile mass was not in place, or the journalist did not understand how it worked.

Would you believe that Chaput demanded that an ambulance and medics be requested before boarding the airship – a flying machine which, let us recall, seemingly had not flown yet? That requirement of the journalist was ignored, which did not please him.

Did you know that Chaput later became the first chief editor of a major daily newspaper in Sherbrooke, Québec, yours truly’s homecity? That gentleman was sacked in July 1910, however, only 5 or so months after the birth of La Tribune. He was a free mason, you see, and the Roman catholic church, then supremely powerful in Québec, was fiercely opposed to freemasonry, because of its espousal of liberalism and free thought. The fact that Chaput was a francophone catholic only increased the ire of Québec’s reactionary clergy, but back to our story.

Even more than La Presse, La Patrie underlined the extent to which Filion’s slightly too heavy weight limited the performance of his machine. In fact, the inventor seemed unable to leave the ground.

The Filion airship was a fairly primitive machine with limited performance, pointed out La Patrie. This being said (typed?), it could be maneuvered without too much difficulty. Undoubtedly, the addition of a gasoline engine would significantly improve the performance of that airship.

An English-language Montréal weekly, Montreal Weekly Witness, was no more enthusiastic than its French-language counterparts. According to its journalist, none of the 3 unidentified young men who took place in the nacelle, successively of course, managed to rise higher than the tops of trees, which was not particularly surprising given the presence of the cables mentioned by La Patrie. Worse still, each time the airship did not stay in the air for long. However, the results obtained by these young people were superior to those obtained by Filion. If we are to believe Montreal Weekly Witness, the inventor could not even leave the ground.

Unless I am mistaken, no English-language Québec or even Canadian newspaper other than Montreal Weekly Witness mentioned Filion or his airship, whether in 1904, before 1904 or after 1904, which was somewhat curious. I would certainly not dare to insinuate that this was a demonstration of anti-francophone prejudice, but that lack of coverage troubles me. Anyway, let us move on.

At least 2 photographs of the Filion airship, presumably taken in July 1904, still existed as of 2022. They may, I repeat may, have been published as photographic postcards around 1904-05. Here is a third one which did not seem to give birth to a postcard.

The Filion rigid airship in full flight. Anon., “Le Sport – Aérostation – Au Parc Mascotte enfonce Santos Dumont. La Patrie, 6 August 1904, 2.

And no, I do not understand the meaning of the caption for that photograph either, but I digress.

Encouraged by the media coverage surrounding the July 1904 demonstration, Filion planned to replace the pedal and gear mechanism of his airship with a small gasoline engine.

A public flight scheduled for the first Sunday of August, in Montréal, at Mascotte Park, now long gone, did not seem to take place, which was a shame.

Would you believe that Filion had hoped to use the funds collected that day to further improve his airship? In fact, he had hoped to go to St. Louis, Missouri, where, between April and December 1904, an international exposition, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the most stupendous entertainment the world had ever seen, if I may paraphrase a newspaper headline of the time, was held.

Why the he** did Filion want to go to St. Louis, you ask? A good question. You see, one of the many attractions of the world fair, besides the Games of the III Olympiad, was an aeronautical competition with a grand prize of no less than $ 100 000. To earn this truly titanic sum of money, which corresponds to about 4 100 000 $ in 2022 Canadian currency, a pilot only needed to go around a 16-kilometre (10 miles) circuit 3 times. Nothing to it.

The individual favoured to win the grand prize was, you guessed it, smart person that you are, the aforementioned Santos Dumont. In late June 1904, however, just after he arrived in St. Louis, the envelope of his airship, the No 7, seemingly known as Coursier, was slashed beyond repair while stored in a hangar for the night. There would be no flight on 4 July, the American national holiday.

The elite and media in St. Louis were beside themselves. Profoundly disappointed, Santos Dumont returned to Paris within days. The person or persons responsible for the destruction of his airship, most likely American nogoodniks, were never identified.

A cynical person, not yours truly of course but perhaps you, who knows, might wonder if the airship was sabotaged by one or several people under the orders of at least one of the people who, having offered the famous $ 100 000, feared that Santos-Dumont could carry out the requested flight. Just sayin’.

And yes, my sport loving reading friend, the Games of the III Olympiad were among the most ridiculous ever held – and this time, may I submit that you are the one who is digressing?

An article published in January 1907 in a regional weekly, Le Peuple of Montmagny, Québec, suggested that Filion wanted to undertake new flight tests in the spring with his airship, which would this time be equipped with a small gasoline engine. Then short of money to carry out that work and relaunch his project, the inventor called for help. Unfortunately, that appeal was seemingly not heard.

Yours truly must admit to knowing nothing about Filion’s life after 1907. His precious airship was in all likelihood scrapped.

I wish I could say (type?) that the use of a moving mass to control an airship in the vertical plane, in other words in pitch, became commonplace. That was unfortunately not the case. That type of flying machine has, is, and in many cases will continue to rely on elevators and water ballast.

Allow me to wish you a good week.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)