An American whiz kid at the dawn of the Space Age who became a professor at the Propulsion Research Center of the University of Alabama in Huntsville: James Bertram Blackmon, this is your life, Part 1

Welcome yet again to the wonderful world of space, my reading friend. As we both know, the Space Age came of age during the Cold War, that dreadful period of the 20th century that our species seems quite intent on returning to. Indeed, yours truly would like to offer a life story lifted from the pages of history dating from the second half of the 1950s – and beyond. Let us begin without any further ado.

James Bertram “Jim / Jimmy” Blackmon was born in December 1938, in Charlotte, North Carolina. Would you believe that this gentleman was born precisely 10 years after my father? I kid you not, but I do digress. Sorry.

Blackmon became hooked on science and technology before he was 10 years old, thanks in part to the science kits given to him as presents. Mind you, he also made and flew simple model airplanes. Having read that oxygen and hydrogen would burn when brought together, the boy made at least one experiment, using balloons. Whoosh! Actually, one can wonder if there was a second one.

Around the age of 14, in 1953, Blackmon, a bright Homo sapiens if there was one, began to work on what, at least initially, seemed like a crazy project. You see, the teenager began to design a rocket. As time went by, Blackmon read every article, book, report, etc. he could get his hands on. And no, there was not a whole lot to read. The actual construction work was done when school was out for summer, if I may paraphrase the words sung by American rock singer Vincent Damon Furnier, in other words, Alice Cooper, in the 1972 (!) song School’s Out. Blackmon earned the cabbage he needed to buy the various components of his rocket by mowing countless lawns, among other things. Would you believe that several of said components were bought at a local hardware store?

An avid naturalist and enthusiastic educator, the well known and respected director of science teaching for the schools in Charlotte, Herbert “Dr. Heck” Hechenbleikner, helped Blackmon as best he could.

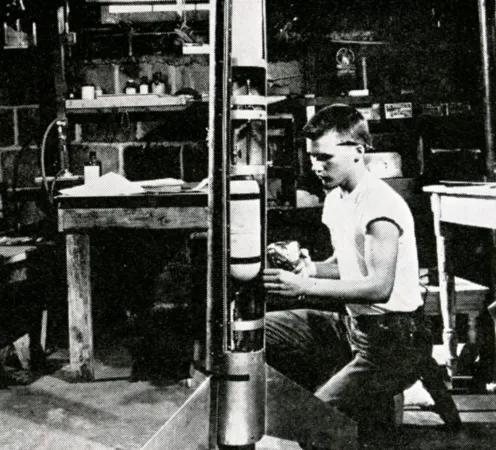

The crazy thing was that, by July 1956, the rocket was all but complete. And if you dare to doubt that statement, please have a look at the photograph with which we began today’s issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Would you believe that an American industrial giant mentioned in a December 2019 issue of that same blog / bulletin / thingee, Aluminum Company of America, had graciously provided at least part of the aluminium the teenager needed to build his 1.8 metre (6 feet) (2 metre (6 feet 6 inches)?) tall liquid fuel rocket?

Blackmon planned to test his rocket his August 1956. He very much intended to take all the required precautions so that no one would get hurt, and nothing would get damaged.

Blackmon’s rocket was a pretty impressive piece of engineering. Its combustion chamber had a dry ice cooling system, for example, for protection against the astronomical temperatures it would have to withstand. Said temperatures would be achieved by the combustion of the rocket’s fuel (gasoline) and oxidiser (liquid oxygen), and…

What is it, my reading friend? You seem puzzled. Ahh, I see. Whereas an automobile, or aircraft, only needs to carry fuel because the oxidiser needed to burn said fuel is the oxygen present in the Earth’s atmosphere, rockets, especially those designed to operate outside of said atmosphere, need to carry their oxidiser. Liquid oxygen being not all that hard to obtain, Blackmon chose it for use on his rocket.

Oh yes, the sleek nose cone of the rocket consisted of a modernist aluminium lampshade, in French abat-jour (Hello EP!), worth $ 5, which corresponds to approximately $ 75 in 2023 Canadian currency. Said lampshade belonged to Blackmon’s roommate at Phillips Academy, in Andover, Maine, one of the oldest (1778) high schools in the United States. Would you believe that, having found said lampshade, Blackmon pretty much built the rest of his rocket around it?

As diligent as he had been, Blackmon knew that rocket science was no easy thing. He did not know what would happen at ignition time, for example. The rocket might reach an altitude of 2 200 metres (7 200 feet) – or blow up when the switch got flipped.

Informed of what Blackmon was up to, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), an organisation with powers to regulate all aspects of civilian aviation in the United States mentioned several times since June 2018 in our awe inspiring blog / bulletin / thingee, regretfully had to inform him that its lawyers were of the opinion that launching his rocket would be a violation of air regulations. It might after all hit a passing aircraft.

The CAA also informed Blackmon that he would have to test his rocket at a proper test range, presumably one operated by the military.

How the CAA heard about the rocket was unclear, at least to me. Blackmon might have contacted that organisation himself. This being said (typed?), the culprit might well have been a journalist working for the largest evening daily in North Carolina, The Charlotte News of… Charlotte. While that gentleman did not want to throw a monkey wrench in Blackmon’s preparations, he was aware that some people, one of them the manager of Douglas Municipal Airport, near the city, had expressed concern.

Although disappointed, Blackmon took it all pretty much in stride. He had no intention to cause an accident. He had, however, become a bit of a celebrity as a result of the articles published in a great many American states by 150+ daily newspapers. Oh yes, before I forget, Blackmon and his rocket were also mentioned by radio and television stations across the United States. Would you believe that at least one daily newspaper in Australia published an article about both of them? And here is proof…

The cartoon which accompanied an article on James Bertram Blackmon published by the general Australian newspaper of record of the 1950s, The Argus. Anon., “Rocketing to fame.” The Argus, 9 August 1956, 5.

But back to our story and Blackmon’s initial disappointment.

Jack Walton Williams (on the left) and Major Gladden F. Loring, two representatives of the United States Army’s Charlotte Army Missile Plant of Charlotte, North Carolina, examining James Bertram Blackmon’s rocket in the basement of the family’s residence, Charlotte. Anon., “–.” The Press Democrat, 9 August 1956, 2.

Things very quickly brightened up, however, as a result of a visit by two representatives of the United States Army’s Charlotte Army Missile Plant in… Charlotte, an engineer by the name of Jack Walton Williams and no less than the officer in charge of the plant, Major Gladden F. Loring. These gentlemen were most impressed by Blackmon’s rocket. Their conclusion was that it should be tested at a United States Army test range. This being said (typed?), they were of course unable to promise that such a test would indeed take place.

Williams and Loring might, I repeat might, have been the first United States Army people to be puzzled by the exquisite nose cone of Blackmon’s rocket. Their reaction when informed that it was an aluminium lampshade was not recorded.

By the way, would you believe that the Charlotte Army Missile Plant might, I repeat might, have produced components of the Douglas M31 and M50 / MGR-1 Honest John short range unguided ground to ground nuclear-tipped rockets, weapons of mass destruction mentioned in July 2022 issues of our tremendous blog / bulletin / thingee?

The production of such components might not have been all that surprising given that the missile plant in question was operated by a well known and respected American aircraft manufacturing firm mentioned many times in our you know what since July 2018, namely Douglas Aircraft Company Incorporated, but I digress.

Within a couple of days, a representative of Redstone Arsenal, a rocket research and development facility located near Huntsville, Alabama, and controlled by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), an agency of the United States Army, contacted Blackmon and…

And yes, my slightly over enthusiastic reading friend, Redstone Arsenal was indeed mentioned in a July 2022 issue of our prodigious blog / bulletin / thingee. ABMA, on the other hand, was so honoured a few times since February 2019. May I return to my derailed train of thought? Thank you.

A representative of Redstone arsenal, state I, contacted Blackmon and graciously offered to have the rocket tested there. There would be a static test first, on a special outdoors stand. If the rocket was deemed safe, it might be launched some time later. Inquiries were being made to see if Blackmon could be present at either time, or on both occasions. The teenager was understandably over the moon. No pun intended. Well, maybe a little. In any event, the rocket was carefully flown (free of charge?) to Huntsville, in mid August, in an airliner.

These photographs show how James Bertram Blackmon’s rocket went from the family’s residence to Douglas Municipal Airport, Charlotte, North Carolina. Emery Wister, “May Be Fired Tuesday – Army ‘Inducts’ Jimmy’s Rocket.” The Charlotte News, 14 August 1956, 1.

James Bertram Blackmon and some Eastern Airlines Incorporated people are seen here as they put the young man’s rocket in a crate prior to takeoff. Anon., “–.” The Troy Messenger, 29 November 1956, 1.

This staged photograph showed the rocket put together by James Bertram Blackmon soon after it was taken out of the Eastern Airlines Incorporated aircraft which had carried it, Huntsville-Madison County Airport, near Huntsville, Alabama. The gentlemen were, from left to right, Stillman A. Bell, pilot of the aircraft, John W. Womble, deputy chief of the Rocket Development Laboratory at Redstone Arsenal, Charles Northrop, flight test chief at the Test and Evaluation Laboratory at Redstone Arsenal, and David H. Newby, chief of the Test and Evaluation Laboratory. Anon., “Rocket Experts Peer, Poke At Jimmy’s Product Today.” The Charlotte News, 15 August 1956, 21-A.

The United States Army was so pleased by the coverage the story was getting that it sent to Redstone Arsenal a Specialist Third Class in the United States Army Reserve on active duty for 2 weeks in South Carolina, with an infantry division, the journalist of The Charlotte News who had broken the story to tell you the truth, to cover the ground testing and, hopefully, the launch of Blackmon’s rocket.

Specialist third class Charles Bishop Kuralt, on the left, receiving his marching order from his commanding officer, the commanding officer of the 108th Infantry Division, Major General Thomas M. Mayfield, Fort Jackson, South Carolina. Anon., “Rocket Experts Peer, Poke At Jimmy’s Product Today.” The Charlotte News, 15 August 1956, 21-A.

The journalist in question was Charles Bishop Kuralt. He was not yet 22 years old. Kuralt would go on to become an award winning journalist (newspaper, radio, television) and author most widely known for his long career (1957-94) with Columbia Broadcasting System Incorporated. Yours truly remembers seeing and hearing him during the time (1979-94) he hosted CBS News Sunday Morning, but I digress.

The engineers at Redstone Arsenal, the deputy chief of the Rocket Development Laboratory, John W. Womble, among them, were impressed by the homemade rocket. The rocket engine designed by Blackmon was surprisingly similar to engines recently developed at the arsenal. To quote the commanding officer of Redstone Arsenal, Brigadier General Holger Nelson Toftoy, Blackmon had “a really remarkable grasp of the basic principles of rocketry for a boy of only 17 years with no formal training or experience in the field. I only wish more American youngsters had Jimmy’s enthusiasm for science.”

At this point, the nitpicker in yours truly feels compelled to point out that putting together a rocket feels like a technical / technological achievement more than a scientific one. Just sayin’.

Several engineers at Redstone Arsenal were seemingly puzzled by the exquisite nose cone of Blackmon’s rocket. Informed that it was a simple lampshade, they were suitably impressed by the teenager’s ingenuity. One of them noted, with a smile perhaps, that the arsenal would have spent “thousands of dollars and [used] all kinds of complicated formulae to determine the exact curve” of the rocket’s nose.

And yes, you are quite right, my reading friend, Toftoy was indeed mentioned in a July 2022 issue of our stellar blog / bulletin / thingee.

As it turned out, the engineers at Redstone Arsenal concluded that, even though the rocket’s engine was well designed, the small war surplus aircraft oxygen bottles used to contain the gasoline and liquid oxygen might not be strong enough to resist the pressure they would be subjected to when pressurised prior to launch. Testing the rocket, even on the ground, was therefore out of the question. Blackmon was understandably disappointed.

Things brightened up immediately, however. You see, a Redstone Arsenal person speaking on behalf of Toftoy invited Blackmon and his father to come over for a visit, so that the teenager could chat with some engineers and see some of their lethal creations. Blackmon was understandably over the moon.

Would you believe that Blackmon was offered a position at Redstone Arsenal as soon as he got out of college / university?

James Bertram Blackmon and his father, James Bertram Blackmon, on the right, being welcomed at Redstone Arsenal by two aeronautical engineers and missile scientists, William Ames “Bill” Davis, Junior, and Billy Spencer “Spence” Isbell, Redstone Arsenal, Alabama. Anon., “Rocket Maker, 17, Tours Arsenal.” Democrat and Chronicle, 21 August 1956, 15.

Blackmon and his father duly went to Huntsville, in August, aboard a small military aircraft. They were welcomed at the airport by a small group of people which included representatives of the American Rocket Society (ARS) and Rocket City Astronomical Association, a Huntsville group headed by the director of the Guided Missile Development Division at Redstone Arsenal, Wernher Magnus Maximilian von Braun.

Blackmon ended up getting an honorary ARS membership.

James Bertram Blackmon and his father, James Bertram Blackmon, aboard the small military aircraft which carried them from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Huntsville, Alabama. Charles Kuralt, “Alabama Meeting of Minds – Jimmy Lives Rocket-type Dream.” The Charlotte News, 20 August 1956, 13.

A brief digression if I may. Is yours truly imagining things or does the door of the small military aircraft which carried Blackmon and his father from Charlotte to Huntsville look suspiciously like that of a United States Army de Havilland Canada L-20 Beaver utility aircraft? Just sayin’.

And yes, that digression allowed me to point out that the prodigious collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes a Beaver. Do you have a problem with that? If so, too bad, so sad. Better yet, the Beaver was at the heart of 2 August 2022 issues of our wonderful blog / bulletin / thingee.

It is worth noting that von Braun, a key figure in the German rocket program during the Second World War and of the American space program during the Cold War, had been a member of both the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (1937) and the Allgemeine SS (1940), a branch of the monstrous Schutzstaffel. Like many Germans, he seemingly joined both organisations to improve his career prospects.

Speaking (typing?) of career prospects, von Braun skedaddled westward across Germany in late April, early May 1945 in order to surrender to a United States Army unit, out of conviction that his abilities might be better appreciated in the United States than in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), a country where Germans were hated with a vengeance, for very good, war-related reasons. The American government was also a tad less brutal than that of the USSR. Mind you, the climate in Alabama proved to be a tad less brutal than that of Siberia.

Von Braun’s National Socialist past was carefully buried for many years. Incidentally, he became a naturalised American citizen in April 1955. And yes, von Braun was mentioned several times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since January 2019, but I digress.

After leaving the airport, Blackmon and his father, James Bertram Blackmon, an advertising man at the aforementioned The Charlotte News incidentally, visited the observatory of the Rocket City Astronomical Association, then under construction. Later that day, they watched documentary films on German and American missiles, as well as space travel. Blackmon and his father spent the night in the posh digs used by United States Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson when the latter visited Huntsville. Wow…

James Bertram Blackmon having a chat with the director of the Guided Missile Development Division at Redstone Arsenal, Wernher Magnus Maximilian von Braun, Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, August 1956. Jim Show, “Youngsters finding a new fad: Rockets.” The Birmingham News (Magazine), 9 March 1958, 5.

The following day, Blackmon and his father visited several Redstone Arsenal laboratories and shops, where they seemingly saw Bell / Douglas SAM-A-7 / M1 Nike Ajax anti-aircraft missiles and Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Firestone SSM-A-17 / M2 Corporal short range nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, with many (12? 20?) journalists and photographers in tow. They saw no less than 4 missile launches. Blackmon even had a chance to chat with von Braun. He was understandably thrilled, and…

Why the shocked look, my reading friend? Did you not know that American giant Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, a firm mentioned in September 2019 and February 2022 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, and Bell Telephone Laboratories Incorporated, a firm co-owned by American Telephone & Telegraph Company and Western Electric Company, made weapons of mass destruction in the 1950s and / or 1960s – a case of turning ploughshares into swords, if yours truly may say (type?) so? Well, now you do know, but back to our story.

Would you believe that Blackmon was asked to talk about his rocket in front of an audience consisting of Redstone Arsenal engineers and other people, including a pair of United States Army generals?

Incidentally, some of the questions Blackmon asked during his tour of the Redstone Arsenal laboratories and shops were so incisive / insightful that the engineers had to decline answering them. “That’s classified material,” they added, quite possibly with a smile.

It went without saying that Blackmon’s visit to Redstone Arsenal, a very sensitive and secretive facility, was mentioned in dozens and dozens of American daily newspapers, not to mention at least 10 or so Canadian daily newspapers published in 4 provinces. Oddly enough, French language newspapers in Canada had nothing to say about Blackmon or his rocket.

Given the amount of information that yours truly can regale you with, my reading friend, I find myself in the awkward situation of having to postpone until next week the presentation of the rest of that information. Sorry.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)