“A stone fallen from the Moon… or elsewhere” – The Bendegó meteorite, part 1

Bom dia, amiga leitora ou amigo leitor. Como vai? […] Bem, bem. É com prazer que vos dou as boas-vindas a uma história fascinante, a história do meteorito de Bendego.

In other words, it is with pleasure that I welcome you to examine a fascinating story, the story of the Bendegó meteorite.

Yours truly will not teach you anything by telling you that stones, nay, mountains can fall from the sky at any moment. Just think of the object which fragmented at high altitude in February 2013, in the sky over the administrative region of Chelyabinsk, Russia, not too, too far from the border which separates that country from Kazakhstan.

The energy released by the fragmentation of the object in question corresponded to 450 000 or so metric tons (440 000 or so imperial tons / 500 000 or so American tons) of trinitrotoluene, TNT for short. An abbreviation which happens to be the title of a song released in 1975 (!) by the Australian hard rock group AC/DC.

As I have stated in the past, I personally prefer the 1990 song Thunderstruck by the same band. (Hello, EP and EG!) But I digress.

By the way, the energy released by that object corresponded to that which would have been released by approximately 30 nuclear bombs similar to the one that the American government dropped on the city of Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1945, killing 140 000 or so people, for the most part women, children and the elderly, between that month and December 1945.

Would you believe that said object was an asteroid between 17 and 20 metres (about 55 to 65 feet) in diameter? A space speck in short.

An even smaller object made its way through the Earth’s atmosphere at an undetermined date, many years ago, and crashed in a vast semi-arid region on the eastern tip of South America, 35 or so kilometres (20 or so miles), I think, from the site where the village of Pico-Arassu, renamed Monte Santo in 1786, captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos, state of Brazil, would be built towards the end of the 18th century.

In fact, it was in 1784, perhaps in June, in other words 240 years ago, on a height, near the Bendegó stream, that a certain member of the da Mota Botelho family, in all likelihood young Bernardino da Mota Botelho, discovered a rock which differed from the granite and gneiss bedrock of the area, a rock which always seemed to remain cold to the touch, and this while he was perhaps searching for a lost cow.

A clarification if I may. At the time which concerns us, in other words towards the end of the 18th century, the state of Brazil, present-day Brazil, was a Portuguese colony, but back to our story.

Da Mota Botelho, or a member of his family, his father, Joaquim da Mota Botelho, perhaps, immediately contacted, well, as soon as he could, the governor of the captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos, Rodrigo José de Meneses e Castro.

In 1785, said governor contacted the captain-major of the village of Itapicuru de Cima, captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos, and asked him to see what was going on. Bernardo Carvalho da Cunha left immediately. Well, as soon as this request reached him and as soon as it was possible for him to reach Pico-Arassu, a village located 150 or so kilometres (more than 90 miles) northwest of Itapicuru de Cima, and this as the crow flew.

Need yours truly mention that there were no roads between Itapicuru de Cima and Pico-Arassu? I thought not.

Once there, Carvalho da Cunha observed that some parts of the rock seemed to be made of iron, and others of stone. He also believed that said rock contained gold and silver.

Informed of this fact, de Meneses e Castro asked Carvalho da Cunha to do everything possible to transport the rock to the nearest port, Aracaju, captaincy of Sergipe, state of Brazil. This done, it would be placed on a ship to bring it to São Salvador da Bahia de Todos os Santos, the capital of the captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos.

Carvalho da Cunha immediately got to work. Well, as soon as that request reached him and as soon as it was possible for him to return to Pico-Arassu.

Once there, Carvalho da Cunha requisitioned 30 or so men to tip the rock. He also supervised the construction of a primitive wooden cart, as well as the construction of a stone path on both sides of the Bendegó stream, near the spot where the extraordinary stone could be seen. He planned to head towards the Itapiranga / Vaza-Barris River, a watercourse that he would follow more or less to Aracaju.

Given that the available men did not have the necessary strength to move the enormous rock, and that the water of the stream was not fit for human consumption, Carvalho da Cunha left the site in order to bring back oxen which were harnessed to the cart in large numbers (80?).

Placing the enormous rock on the cart had certainly been no picnic. Going down the hill on which it was located down to the Bendegó stream was even less so. Indeed, according to one version of the story, the cart accelerated to the point where its axles caught fire (!) from the friction. It ended its course in the bed of the stream, on its left bank. History did not say how many oxen died that day.

According to another version of the story, undoubtedly a less spectacular and deadly one, the fixed axles of the cart did not allow it to go around a group of rocks which stood in its way, near the Bendegó stream. Stuck on site, the cart and its precious cargo were abandoned.

In either case, the cart and its precious cargo had not travelled more than 200 or so metres (650 or so feet).

In any event, informed after a while of what had happened, de Meneses e Castro informed his superior, in Lisboa / Lisbon, Portugal, the secretary of state of the navy and overseas lands, Martinho de Melo e Castro. He took the opportunity to send some fragments of the rock so that they could be examined.

Things remained as is until 1810. That year, an English mineralogist hired by the government of the captaincy of Bahia de Todos os Santos, Aristides Franklin Mornay, discovered, near São Salvador da Bahia, a spring whose waters contained quite a bit of iron. Some people remembered that a few other thermal springs had been discovered, further north, a little before or after 1780.

Given that the person who then controlled the destiny of the state of Brazil, Prince Regent João Maria José Francisco Xavier de Paula Luís António Domingos Rafael of house Bragança, wished to know if thermal springs were found on Brazilian soil, the authorities asked Mornay to go to the site where those discovered around 1780 were located, and…

Yes, yes, the prince regent and not the viceroy of the state of Brazil. You see, the royal family of Portugal had arrived on Brazilian soil in January 1808, following the invasion of the country by Emperor Napoléon Ier, born Napoleone di Buonaparte, a megalomaniac tyrant mentioned in several / many issues of our dazzling blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since December 2017.

Mornay appearing somewhat unsure that he wanted to make the trip, friends mentioned the extraordinary stone discovered in 1784. He decided to go. The Brazilian government was happy to provide him with an escort and significant support.

Mornay examined said stone, still placed on its cart, in January 1811. He measured it and detached a few fragments, with much difficulty. Well, him or members of his escort.

At least some of those fragments were subsequently shipped to England, to well-known figures in the British scientific community, the English chemist / physicist William Hyde Wollaston and the Bavarian-English mineralogist John Henry Heuland, born Johann Heinrich Heuland, for example, but back to our extraordinary stone.

The top and sides of that enormous rock were covered in a thin layer of rust. This removed, the rock revealed itself to be both shiny and covered with small indentations. Its underside was, however, covered with a thick layer of rust. Since the rock was clearly magnetic, it appeared to contain a lot of iron.

Mornay thought that it was a meteorite, an assertion which demonstrated that this mineralogist followed the scientific news of his time.

As matter of fact, did you know that right until the late 1700s, if not the early 1800s, virtually all members of Europe’s scientific elite consistently mocked the illiterate peasants who claimed they had seen rocks falling from the sky?

I mean, peasants of 1800, what did they know? What could one possibly learn from observation? Had they consulted the 2 100 or so year old treatises of the great Greek philosopher / polymath Aristotélēs / Aristotle, a smart guy who had not wasted his time observing, they would have learned that rocks cannot fall from the sky. Period. Observation? Humbug. One might as well state that women deserve to have the same rights as men, or that vaccines are not part of a plot to enslave humanity.

The Ferris wheel of science began to turn in April 1803, on 26 April to me more precise, an auspicious day if I may state so, when a few thousand stones fell from the sky in the region of L’Aigle, France. Informed of that news, the government of the French Consulate sent a young engineer / professor of mathematics to the scene. Jean-Baptiste Biot submitted a report in July in which he confirmed the presence of stones falling from the sky, a fall confirmed by testimonies collected in more than 20 surrounding villages.

The prestigious Académie des sciences, in Paris, France, an organisation mentioned several times in our equally prestigious blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since July 2018, took note of said report and had to face the facts. Aristotélēs was out to lunch, but back to our topic.

It should be noted that the dimensions calculated by Mornay differed a tad from those obtained more recently, namely 2.2 or so metres (7 feet 3 or so inches) long, 1.45 or so metres (4 feet 9 or so inches) wide and 60 or so centimetres (2 or so feet) tall.

The Bendegó meteorite weighed / weighs 5 360 or so kilogrammes (a little over 11 800 pounds). The weight Mornay calculated off the top of his head was around 6 350 kilogrammes (14 000 or so pounds), by the way, which was a pretty good approximation.

By the way, again, as you already suspected, my smart reading friend that you are, our interplanetary traveler was an iron meteorite / siderite.

Also in 1811, a team attempted to move the rock. It was under the orders of a Brazilian diplomat / politician / soldier, the Marquess of Barbacena, born Felisberto Caldeira Brant Pontes de Oliveira Horta. That attempt failed.

In 1819 or 1820, or as early as March 1818 perhaps, two Bavarian scientists who traveled through Brazil from 1817 to 1820, the biologist / explorer Johann Baptist Spix and the botanist / explorer Carl Friedrich Philipp Martius, examined the meteorite, after having it dug up by people of the place. The easiest fragments to detach having been torn off by those people over the years, it was with much difficulty that Spix and Martius obtained a few fragments, thanks to the efforts of the local people of course and after having maintained a fire on or under the meteorite for almost 24 hours. I kid you not.

Things remained as is until 1883. Towards the end of that year, the head of the mineralogy and paleontology collections of the Museu Nacional of Rio de Janeiro, province of Rio de Janeiro, empire of Brazil, asked one of the engineers involved in the development work on a large Brazilian watercourse, the São Francisco River, to gather information.

Yes, yes, you read right, my reading friend, the empire of Brazil.

You see, when the recently consecrated (February 1818) King of Portugal, João VI, born João Maria José Francisco Xavier de Paula Luís António Domingos Rafael of house Bragança, returned to Portugal in 1821, he left his son and heir, Pedro de Alcântara Francisco António João Carlos Xavier de Paula Miguel Rafael Joaquim José Gonzaga Pascoal Cipriano Serafim of house Bragança e Bourbon, to govern as regent what was then the kingdom of Brazil.

In September 1822, that not quite 24-year-old regent proclaimed the independence of that kingdom and was acclaimed as Pedro I, emperor of Brazil, in October. His father was not too, too surprised by that move and accepted it, but back to the engineer involved in the development works of the São Francisco River.

Theodoro Sampaio willingly complied and sent what he had collected to the head of the mineralogy and paleontology collections of the Museu Nacional, the Brazilian American geologist / geographer Orville Adalbert Derby.

The latter persuaded the director of the Museu Nacional to obtain further information. Having obtained a green light from the secretary of state of business for agriculture, commerce and public works, the Brazilian botanist Ladislau de Souza Mello Netto contacted Luis da Rocha Dias, the engineer who was directing the work to extend the Estrada de Ferro da Bahia ao São Francisco, a railway between two Brazilian cities in the province of Bahia, empire of Brazil, São Salvador da Bahia and Alagoinhas.

In fact, it was undoubtedly the existence of the Jacurici train station, in the village of Vila Bela de Santo Antonio das Queimadas, province of Bahia, and the low probability that a less distant train station would be completed before several years, which aroused the renewed interest of the Museu Nacional, but I digress.

Da Rocha Dias had no objection to sending an engineer to Monte Santo, Province of Bahia, to gather information and see how the meteorite could be transported to the Museu Nacional.

Vicente José de Carvalho therefore went there and got information. He also collected several fragments. His 1886 report indicated that transporting the meteorite over a long distance in a rough mountainous terrain without roads would be no picnic.

De Souza Mello Netto knew only too well that this undertaking was far beyond the resources of his museum. He also knew that the probabilities of success of a request for financial assistance made to the government were very slight indeed. De Souza Mello Netto thus had no choice but to drop the matter.

Things remained as is until June 1887. Following two presentations made in Rio de Janeiro before members of the Sociedade de Geografia do Rio de Janeiro, said society and its influential president, a Brazilian magistrate and politician, the Marquess of Paranaguá, born João Lustosa da Cunha Paranaguá, undertook to have the Bendegó meteorite transported to that city, yes, Rio de Janeiro, which was then the capital of the Empire of Brazil.

The minister of agriculture, trade and public works, the very influential Rodrigo Augusto da Silva, in turn pledged to support the project.

A rich banker who happened to be a deputy for the province of Bahia in the Câmara dos Deputados and first vice-president of that legislative assembly stated he was ready to cover the costs of the project. The Baron of Guahy, born Joaquim Elísio Pereira Marinho, did this largely in order to boost his social standing.

By the way, said costs might, I repeat might, have reached approximately US $10 000, an amount which corresponds to approximately $ 430 000 in 2024 Canadian currency.

It went without saying that the Emperor of Brazil, Pedro II, born Pedro de Alcântara João Carlos Leopoldo Salvador Bibiano Francisco Xavier de Paula Leocádio Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga of house Bragança e Bourbon, gave his blessing to what was being prepared.

Indeed, that monarch’s interest in our meteorite might actually have dated back to 1886. Members of the aforementioned Académie des Sciences had indeed seemingly suggested that he have this unique object transported to a museum, but back to our story.

A surveying engineer and officer of the Brazilian navy, the Armada Imperial, was entrusted with the management of the project. Lieutenant Commander José Carlos de Carvalho might, I repeat might, have owed that honour to his experience of transporting heavy loads during the Paraguayan War / War of the Triple Alliance which had pitted Paraguay against its 3 neighbors (Eastern state of Uruguay, empire of Brazil and Argentine republic) between 1864 and 1870. Paraguay lost. Big time.

Mind you, the fact that de Carvalho was directly involved in at least one of the presentations made before the members of the Sociedade de Geografia do Rio de Janeiro probably did not hurt.

Accompanied by his two closest collaborators, including the aforementioned Vicente José de Carvalho, his cousin, in fact, de Carvalho left Rio de Janeiro on 20 August 1887, by sea.

The team arrived in Monte Santo on 5 September, by land of course, and…

Err, yes, you are quite correct, my perspicacious reading friend, it was through his cousin who had seen the meteorite that de Carvalho discovered that interplanetary visitor and became fascinated by it.

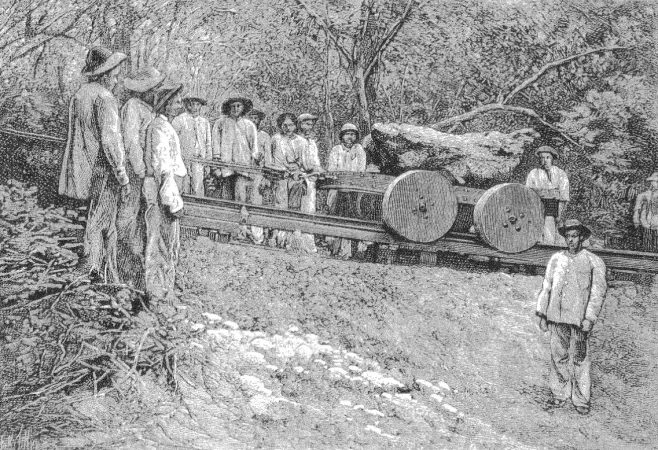

The Bendegó meteorite on its cart in the bed of the Bendegó stream, near Monte Santo, province of Bahia, empire of Brazil, September 1887. José Carlos de Carvalho, Meteorito de Bendegó: Relatório apresentado ao Ministerio da Agricultura, Commercio e Obras publicas e a Sociedade de Geographia do Rio de Janeiro sobre a remoção do meteorito de Bendengó do sertão da provincia da Bahia para o Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1888), not paginated.

Work to move the meteorite officially began on 7 September, the date commemorating the independence of the Empire of Brazil in 1822. That choice was obviously not accidental.

Aware of the challenges ahead, de Carvalho and his team explored the region to cross, and this in order to choose the least difficult route.

Meanwhile, the staff of the workshop at Aramarys, province of Bahia, of the railway which de Carvalho wished to reach, the Estrada de Ferro da Bahia ao São Francisco, built a cart less primitive than that of 1785.

That hammer-beaten iron cart designed according to de Carvalho’s wishes could roll on 4 wooden wheels or 4 cast iron wheels of smaller diameter, attached to the wooden wheels, depending on whether it rolled on the ground or on rails. Yes, yes, rails. The cart would in fact carry out (a small?) part of the upcoming journey on rails placed on the ground, and removed after its passage, I think.

By the way, the Estrada de Ferro da Bahia ao São Francisco belonged to an English firm created for this purpose in 1855, Bahia and San Francisco Railway Company.

And you have a question, do you not, my reading friend? Why did the chicken cross the road? Sorry, sorry. How did the cart get to Monte Santo? A good question. It arrived at Monte Santo at the end of September 1887, thanks to the efforts of many oxen, as shown in the following photograph.

The arrival of Lieutenant Commander José Carlos de Carvalho’s cart and team in the vicinity of Monte Santo, province of Bahia, empire of Brazil, September 1887. José Carlos de Carvalho, Meteorito de Bendegó: Relatório apresentado ao Ministerio da Agricultura, Commercio e Obras publicas e a Sociedade de Geographia do Rio de Janeiro sobre a remoção do meteorito de Bendengó do sertão da provincia da Bahia para o Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1888), not paginated.

As you may have guessed, the rest of this exciting story will reach you shortly.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)