“Looks Like An Animated Pipewrench,” but it flew 70 years, 2 months and 6 days ago; Or, How a Blériot Type XI made in Alberta performed an illegal 1 hour and 40 minute return flight from Calais to Dover in July 1955, part 2

As predicted in the 1550s by the world-famous French apothecary / astrologer / author / physician Michel de Nostredame, you came back, my reading friend, and… No, yours truly does not believe in astrology. Astrology is utter nonsense and pure hogwash. My horoscope told me so.

I used that introduction to this second part of our article on the Blériot Type XI aircraft constructed in Calgary, Alberta, in 1952-53, by students of the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (PITA), because I could not think of an introduction I had not used moult times before. Given your reaction, I shall refrain from using it again. Ever.

So, shall we begin?

In late May 1955, Jean Henri Brion Chopin de La Bruyère, one of the co-owners of said Type XI, lifted off from Calgary Municipal Airport, in… Calgary. The flight went swimmingly.

After alighting back on earth, however, de La Bruyère began to worry that his machine, which had no brakes, might roll off the paved runway onto grass, gravel, or something. He hopped out of the aircraft as is it rolled along, at a speed of 40 or so kilometres/hour (25 or so miles/hour), and managed to stop it before it rolled off the runway. In doing so, however, he broke a foot.

De La Bruyère spent the night at the Colonel Belcher Hospital in Calgary before boarding an airliner going to Edmonton, Alberta, his place of residence, where the staff of the University Hospital put a cast on his foot.

Oddly enough, back in July 1909, when he had crossed the Channel, the French aviation pioneer Louis Charles Joseph Blériot also had to deal with an injured foot. In early July, the asbestos insulating sleeve covering an exhaust pipe on a Type XI had broken loose during a flight at the very first air meet held on planet Earth, the Concours d’aviation held near Douai, France, in late June and early July. The burns suffered by Blériot were very severe, and painful. He was still using crutches on the day he crossed the Channel, but back to our story.

As you might well imagine, the newspaper reports on the upcoming cross-Channel flight of the Type XI caught the eye of many philatelists around the globe who asked de La Bruyère if he would be willing to carry several letters with him during said flight, letters that he would endorse and mail after alighting in England. The young pilot readily agreed to do so.

Slightly before the middle of June, the Type XI took part in the air show held on Air Force Day at Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Station Namao, near Edmonton. The winds that day were so strong, however, that Alastair Auld « Sandy » Mactaggart, de La Bruyère’s business partner and second co-owner of said Type XI, chose not to fly. The Type XI did, however, taxi before the crowds which attended the air show. And yes, a number of RCAF people held the aircraft to make sure the winds would not flip it over.

A niece of Blériot who happened to live in Morinville, Alberta, was on hand to chat with Mactaggart and look at the Type XI. Marie-Paule Blériot was thrilled to be the special guest of the RCAF.

In any event, the Type XI was to be crated very soon after that air show. The aircraft would then be put on a train on its way to the port of Montréal, Québec. It would then be put on a ship going to France.

The gentleman who had supervised the construction of the aircraft, Stanley N. “Stan” Green, would follow suit not too long after that. He was to cross the Atlantic Ocean by sea and was scheduled to arrive in France before the middle of July, to re-assemble the Type XI and get it ready for its cross-Channel flight.

De La Bruyère and Mactaggart planned to fly to France in mid-July. Mactaggart would tag along as a relief or spare pilot in case de La Bruyère found himself unable to fly.

At least, that was the plan.

Given the change of ownership of the Type XI, however, yes, the one completed in 1953 that you read about in the first part of this article, given also the fact that this aircraft did not meet modern airworthiness requirements, the Controller of Civil Aviation of the Department of Transport, Robert E. “Bob” Dodds, informed de La Bruyère and Mactaggart in mid-June that the Type XI would not be re-registered. Worse still, it could no longer be allowed to fly in Canada.

This being said (typed?), Dodds added that, given the considerable historical value of the Type XI as a type of aircraft, the two men might want to contact an arm of the Division of Mechanical Engineering of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC), in Ottawa, Ontario. You see, at the time, the National Aeronautical Establishment (NAE) was sponsoring the idea of launching an aviation museum in Canada, presumably in Ottawa. Dodds thought that the NAE would be pleased to acquire the Type XI.

A brief digression if I may. The NAE was mentioned in a December 2022 issue of our breathtaking blog / bulletin / thingee. The NRC, on the other hand, was mentioned many times therein, and this since May 2018. End of digression.

Within days of receiving Dodds’ note, de La Bruyère sent him a note to point out that the Secrétariat général à l’aviation civile et commerciale of the French Ministère des Travaux publics et des Transports would not allow him to cross the Channel if the Type XI did not have a registration or certification, even a temporary or experimental one.

Given the tremendous publicity his flight would give to PITA and Alberta, de La Bruyère asked that the Department of Transport reconsider its decision. Otherwise, the Type XI, which was on its way to France, or so claimed de La Bruyère, would have to be given away to someone in that country, and this after serious expenditures on the part of Maclab Construction Company Limited of Edmonton, the firm founded by de La Bruyère and Mactaggart.

Dodds answered that the department could not reconsider its decision.

Unwilling to give up, de La Bruyère and Mactaggart intended to contact the British Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation to see if it might be willing to grant them a registration or certification.

It might be worth noting at this point that Dodds came to believe that de La Bruyère and / or Mactaggart had piloted the Type XI after the cancellation of its registration.

Interestingly enough, Lieutenant Commander Robert Frank Lavack, the commanding officer of VC 924, the Calgary-based reserve squadron of the Royal Canadian Naval Air Branch of the Royal Canadian Navy, was filmed at the controls of the Type XI during a flight over Calgary Municipal Aircraft. That flight presumably took place before the cancellation of said registration.

In any event, de La Bruyère and Mactaggart put the crated Type XI on a train in late June. Once in Montréal, the aircraft was loaded abord a cargo ship, SS Beaverlodge, also in late June. That ship was bound for the port of Le Havre, France.

And yes, SS Beaverlodge was operated by Canadian Pacific Steamships Ocean Services Limited, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific Railway Company of Montréal, a Canadian transportation giant mentioned several / many times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since April 2018. Canadian Pacific Steamships Ocean Services, on the other hand, was mentioned several times in our unavoidable publication, and this since September 2022, but I digress.

It so happened that 18 000 or so dock workers in various British port cities went back to work in early July after a 6 weeks long strike. As you might well imagine, that work stoppage had seriously affected the loading and unloading of a great many ships, up to 300 per day it was thought, and this both in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. As a result, SS Beaverlodge would arrive in Le Havre only 2 days before de La Bruyère was scheduled to make his cross-Channel flight.

Given the limited time available to him and the fact that the aforementioned Green had been unable to book a berth on a ship because of the strike, de La Bruyère would have to pick up the Type XI and re-assemble it himself in order to get it ready for its cross-Channel flight. How does the expression go again? When it rains, it pours?

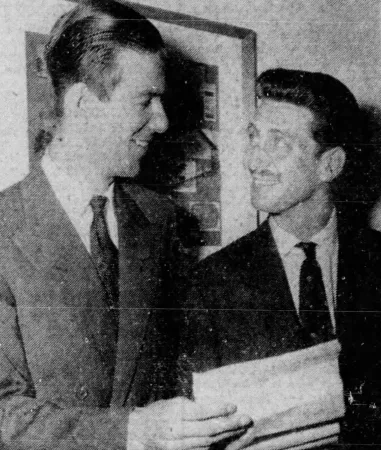

A smiling if struggling Jean Henri Brion Chopin de La Bruyère climbing abord the Société Air France airliner which would carry him to Paris, France. Anon., “–.” The Calgary Herald, 14 July 1955, 31.

De la Bruyère left Canada slightly before mid-July. Would you believe that, even though his cast had been removed, he still had to (chose to?) climb in crutches the moving staircase leading to his Société Air France airliner?

The cross-Channel flight was not the only aerial adventure de La Bruyère had in mind, however. Nay. Would you believe that he (seriously?) pointed out to journalists that he hoped to cross the Atlantic Ocean, between Europe and North America, aboard the Bréguet Br XIX Point d’Interrogation in which Dieudonné Costes and his navigator, Maurice Alexis Jacques Bellonte, had crossed that same ocean, in September 1930. After that 26 year old aircraft got spruced up, of course.

De La Bruyère thought that this aircraft was still owned by Bréguet Aviation Société anonyme, the firm headed by his grandfather, the French aviation pioneer Louis Charles Bréguet, who had died in May 1955 at the age of 75. He was mistaken.

The Br XIX belonged to the Musée de l’Air, France’s national aviation museum, then located at Chalais-Meudon, France. And there was no way on the Flying Spaghetti Monster’s green Earth that the curator of that museal institution, the famous French aeronaut / aviation historian Charles Dollfus, would have allowed such a flight to take place, but back to our story.

Within days of his arrival in Europe, de La Bruyère went to Dover, England, to see for himself the field where Blériot had landed back in July 1909. He thought the field as it existed in 1955 was too small.

Well aware that weather conditions might prevent him from taking off on 25 July, de La Bruyère intended to stay in Calais for several days, until things cleared up.

By the way, de La Bruyère stayed at the Hôtel du Sauvage, in Calais, the very place where, according to some, Blériot had stayed in July 1909.

In mid-July, the Civil Aviation and Communications Attaché at the Office of the High Commissioner for Canada in London, England, sent a note to the Department of External Affairs, in Ottawa, which forwarded said note to the Department of Transport.

John Henry “Tuddy” Tudhope indicated that the British air attaché in Paris, France, presumably the civilian aviation attaché, Raymond Burkett, had informed his superiors that de La Bruyère would attempt to cross the Channel on 25 July.

Tudhope asked if the aforementioned Dodds could confirm that piece of news, and provide the Office of the High Commissioner for Canada in London with some information.

Why was the Office of the High Commissioner for Canada in London interested in de La Bruyère’s activities, you ask, my reading friend? A good question. You see, said office had received several queries from the (British? Canadian??) press, as well as at least one from the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation.

Slightly after mid-July, Tudhope informed the Department of Transport that de La Bruyère had stated to journalists that he had a certificate of airworthiness for the Type XI. Given the decision of that department not to re-register that aircraft after its sale to Maclab Construction, the Office of the High Commissioner for Canada in London and Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation wondered where de La Bruyère had obtained his certificate of airworthiness, provided he actually had one.

The Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation thought that he might have obtained that vital document from the Secrétariat général à l’aviation civile et commerciale. It had, however, been unable to confirm that hypothesis.

Given the late arrival of the Type XI in France, de La Bruyère indicated to journalists 3 or so days before he had planned to lift off that the cross-Channel flight would take place only at the very end of July.

Aware as he was that the French pilot / antique aircraft restorer and constructor Jean-Baptiste Salis was planning a flight across the Channel aboard a Type XI registered in France, de La Bruyère quipped to journalists that the two of them could make the journey together.

A couple of day before the day he had hoped to make his cross-Channel flight, de La Bruyère contacted the Department of Transport by telegram to indicate that he was ready to give ownership of the Type XI back to PITA. He seemingly expected (hoped?) that this return to the original owner of the aircraft would mean that its certification would itself be valid once more.

De La Bruyère added that a Type XI registered in France was now competing with the Canadian Type XI. Indeed, that aircraft had been authorised to fly by the Secrétariat général à l’aviation civile et commerciale. Why could the Department of Transport not do the same thing, asked de La Bruyère?

The department’s answer was that the Type XI was no longer registered in Canada. A re-registration could not be granted because it did not meet modern airworthiness requirements.

This being said (typed?), the department pointed out that it did not object to the planned cross-Channel flight provided that the Ministère des Travaux publics et des Transports and the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation did not themselves object.

On the very day he had hoped to cross the Channel, 25 July, de la Bruyère was aloft near Calais, aboard the light / private plane of a French pilot who had agreed to fly over the area the flight was to take place. Mind you, both men were also going to Calais to see Salis take off toward Dover.

As luck would have it, the two men encountered a fog bank. Eager to land as quickly as possible, the French pilot alighted on what turned out to be a crowded beach. No one was injured but the people present got quite a scare.

When the French pilot tried to take off, the wheels of his machine sank in the sand. Said aircraft nosed over in said sand. Neither the French pilot not his North American passenger were injured.

De La Bruyère, it seemed, just could not catch a break.

Incidentally, the fog as well as some strong winds kept Salis and his Type XI firmly on the ground that day. Those same conditions prevented him from flying the following day.

Those delays kept aloft de La Bruyère’s hope that he might be able to get his Type XI off SS Beaverlodge, reassemble it and get it ready before his French rival crossed the Channel. I know, I know, he was pretty much grasping at straws.

Interviewed by journalists, de La Bruyère wished Salis the best of luck, adding that if the latter flew first, he would follow suit a few days later.

Even so, there were many people in Calais who thought (hoped?) that de La Bruyère and Salis might decide to turn into a race their plans to cross the Channel separately.

Such a race did not happen. You see, Salis left the Aéroport de Calais, near Marck, France, on 28 July 1955, with 5 modern aircraft in tow as escorts. He was cheered.

Salis had hoped to lift off from Sangatte-Blériot-Plage, the site from which Blériot had lifted off in July 1909 but the Secrétariat général à l’aviation civile et commerciale had vetoed the idea.

Salis flew over Dover but did not land there. Nay. The Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation had apparently made it clear that he was to land at an airport, not in a field.

Indeed, Salis landed at Lydd Ferryfield, an English airport southwest of Dover, on the English coast. He was cheered again. One of the individuals present was the Minister of Fuel and Power, Geoffrey William Lloyd. Yours truly presumes that no other member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom could be bothered to show up, sorry, sorry, was available that day.

Would you like to see some English language footage of Salis’ flight and its preparations? Well, here it is…

SS Beaverlodge seemingly arrived at the port city of Antwerpen / Anvers, Belgium, on the day Salis flew, in other words 15 or so days after its expected time of arrival.

In any event, the Type XI was quickly unloaded. It might have arrived at the Aéroport de Calais two days after Salis’ flight.

Where did Salis’ Type XI come from, you ask, my puzzled reading friend? A very good question. Please allow me to stimulate your mental pathways with some sensory input patterns. And yes, I was paraphrasing counsellor Deanna Troi quoting Lieutenant Commander Data Soong.

That chapter of our story had begun in 1953, when Salis and his small team set out to build a Type XI at the request of the elderly widow of Blériot who was hoping that a biographical motion picture on that French aviation pioneer would be made.

Actually, Salis and his team built a pair of Type XIs. You see, the aforementioned Musée de l’Air had ordered one for its collection and Salis decided to make a second one, which would be used in the film.

Indeed, Alice Jeanne “Alicia” Blériot, born Védère, had been contacted, if not harassed, for years by French movie producers and directors eager to put the life of Blériot on the big screen. She had relented in early 1952, but only after stating that she would supervise the creation of a script. Said script, written by the French scriptwriter / author Marie Joseph Albert Mathieu, was ready by June 1952.

Mrs. Blériot hoped that the famous French stage and film actor Pierre Fresnay, born Pierre Jules Louis Laudenbach, an individual who had sided with the collaborationist government of France after the defeat of that country in 1940, would play her spouse.

Sadly, the motion picture in question was never made. This being said (typed?), Salis conducted at least one test flight in the presence of Mrs. Blériot, who was deeply moved.

Unlike de La Bruyère’s machine, one of the Type XIs, the one which ended up in the Musée de l’Air I think, was powered by an engine all but identical to that of the aeroplane piloted by Blériot in July 1909. The machine Salis wanted to pilot across the Channel had a modern engine, but I digress.

The first newspaper articles on de La Bruyère’s plan to cross the Channel, published in May 1955, had caused a bit of a stir in France. Some Paris-based newspapers all but lamented the fact that a foreigner was about to duplicate the historic flight made by Blériot in July 1909.

Salis seemed to agree, here in translation: “I have more right than anyone to repeat Bleriot’s historic flight, he stated to the press, words translated here, for I knew him personally.”

Personally, I do not think that Salis’ argument held water, but I digress. Again.

Certain people within the Ministère des Travaux publics et des Transports might, I repeat might, have encouraged, if not facilitated Salis’ efforts to cross the Channel before de La Bruyère. One or more French magazines might also have provided some financial assistance.

In any event, Salis arrived at the Aéroport de Calais on 23 July. He was surrounded by press photographers, journalists and newsreel camera crews.

His Type XI was quickly assembled.

What happened next will be found in the final part of the saga of the Albertan Type XI, which will reach you next week.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)