Dōmo arigatō, gunsō Electro, mata au hi made: The electronic adventures of Royal Canadian Air Force / Canadian Armed Forces Sergeant Bob Electro

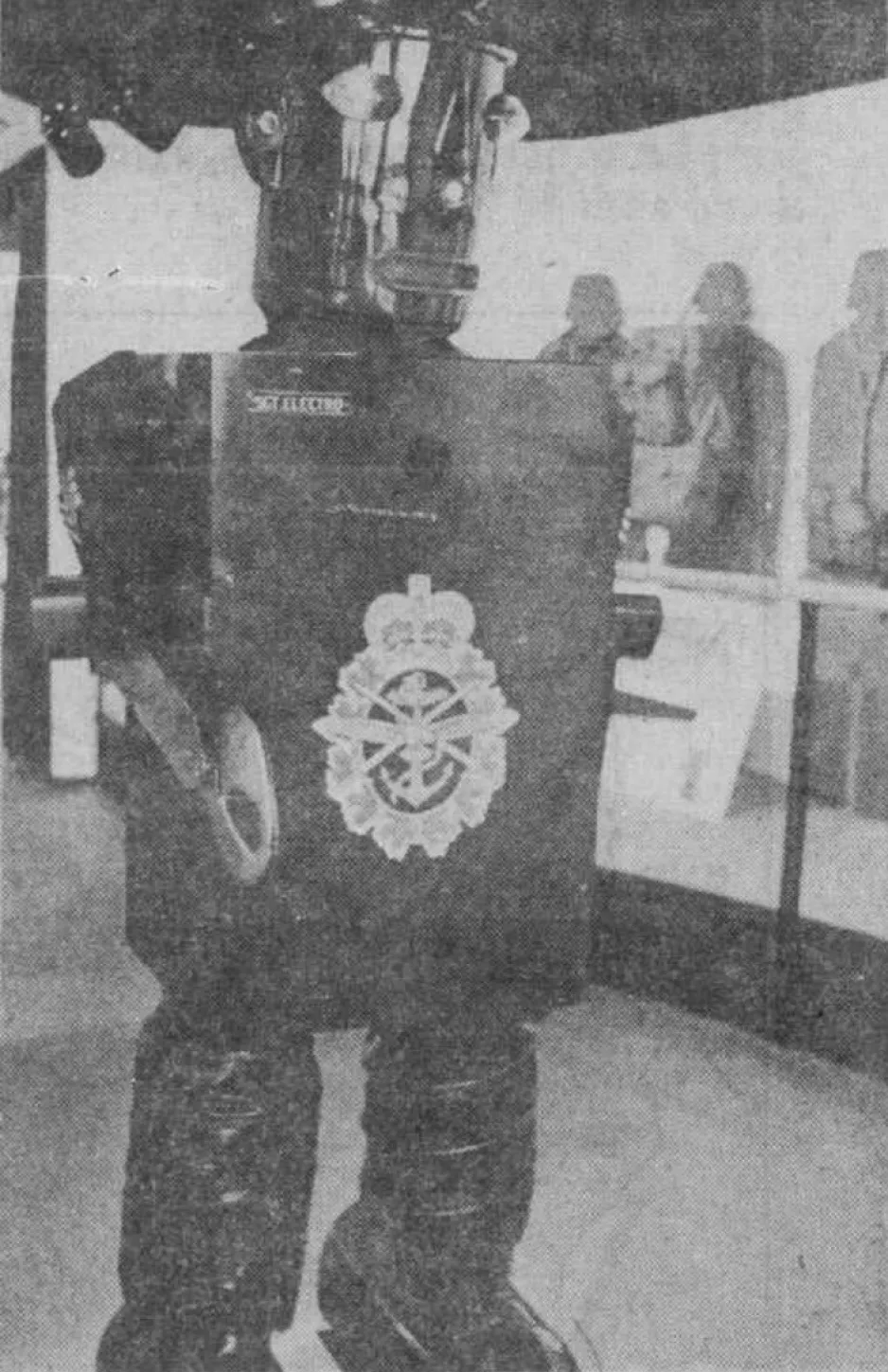

Greetings and salutations, my reading friend. I can only hope that your holiday period was not hectic / taxing. It is with the hope of creating an atmosphere of sweetness and light that I offer you an article on a robot. Let us begin its electronic adventures with the caption of the photograph you saw a few moments ago.

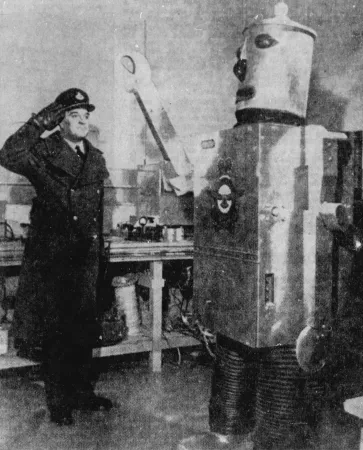

Sgt. Bob Electro of the RCAF base at Clinton, gets no pay, no meals and no weekend passes. The electronic robot was built six years ago for demonstrating radio control in a guided missiles school. It became outdated, however, and was placed in storage last year. Now, it’s been reinstated as a highly popular public relations gimmick at RCAF shows across Canada. Above it prepares to salute Group Capt. [John Gordon] Mathieson, Clinton’s commanding officer.

Did you know that what was then Royal Air Force Station Clinton was created in 1941 to house the very, very, hush hush No. 31 Range and Direction Finding School? So what, you say, my nonchalant reading friend? So what?! I will let you know that this school, which officially opened its doors in July 1941, was the first of two radar schools located in Canada during the Second World War. Some of the first radar sets used in Canada were located in that school.

As well, did you know that John Gordon Mathieson, a gentleman born around 1915, was a member of the crew of the first of several Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) maritime patrol aircraft flown to British Columbia in the summer of 1939? At the time, which happened to be in July, he was a radio operator.

The British-designed but Canadian-made Supermarine Stranraer flying boat flew from RCAF Station Ottawa, near… Ottawa, Ontario, to Ramsey Lake, near Sudbury, Ontario, then to Sioux Lookout, Ontario, then to The Pas, Manitoba. On the second day of its journey, the crew flew to Cooking Lake, near Edmonton, Alberta. On the third day, it flew to RCAF Station Jericho Beach, near Vancouver, British Columbia. The pilot and co-pilot had to battle strong winds for much of the way.

And yes, the Stranraer had initially taken off from the Ottawa River, within spitting distance of where one can today see the main building of the prodigious Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa.

Incidentally, Mathieson would soon leave RCAF Station Clinton, located near… Clinton, Ontario, the home of No. 1 Radar and Communications School. He became deputy chief of staff for communications and electronics at the Canadian headquarters of the North American Air Defense Command, in North Bay, Ontario, during the summer of 1963, but back to our story.

As was hinted in the title of the photograph you saw not too long ago, Sergeant Bob Electro came into existence in 1957. The idea of building that robot dated from June of the previous year, however. Some muckymucks at RCAF Station Clinton requested that a display and training device be put together by the personnel of No. 1 Radar and Communications School to demonstrate remote control electromechanical functions. And yes, the project was very much a local one, an informal / non official local one even.

Whether or not there actually was some sort of missile school at RCAF Station Clinton is not clear, at least to me. Do you know, my reading friend? Yes, the school mentioned in the caption of the photograph you read a few minutes ago. No idea? In any event, it looked as if courses on missile (and space?) technology were given at that location during the early 1960s and, perhaps, the late 1950s, but let us move on.

A machinist and an electronics technician spent a good 6 months designing and putting together a 90 centimetre (3 feet) tall proof of concept prototype of the robot. Satisfied with the results, someone or someones in authority requested in February 1957 that a full size robot be put together. The latter was completed in the early fall of that same year.

A look at the inner workings of Sergeant Bob Electro during the 1960 edition of the Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Ontario. The gentlemen near our friend were, from left to right, Sergeant W.J. Kervin, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Lieutenant Commander William Jeffrey “Bill” Sivell, Royal Canadian Navy, and Leading Aircraftman John Paul, RCAF. Anon., “Toronto.” The Windsor Star, 7 September 1960, 16.

Almost 2 metres (6 feet 6 inches) tall, the robot tilted the scale at around 180 kilogrammes (about 400 pounds). Its metal-covered rectangular body contained a variety of electronic units, several electric motors and two (?) standard automobile batteries. And no, our robotic friend was not rain proof. Incidentally, one or more motors may, I repeat may, have come from a Douglas Dakota military transport plane mothballed / junked by the RCAF.

And yes, the Dakota is represented in the absolutely fabulous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in the form of a Douglas DC-3. (Hello, EG!)

The drum-shaped head of the robot could be tilted up and down, to a point. It could also turn left or right, to a point. The robot’s non functional eyes could blink. And yes, its arms could move back and forth. There was also an articulation at each elbow, I think, and both of its claw-like hands could be opened or closed.

The legs of the robot allowed it to turn left or right, and / or to move forward and backward – albeit slowly and on a flat surface. Incidentally, an actuator designed to move the flaps of a Lockheed / Canadair T-33 Silver Star, the standard jet-powered training aircraft of the RCAF at the time, activated said legs.

Need yours truly remind you that the absolutely fabulous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Silver Star? I thought not.

Before I forget, do you know the song which starts with the following lyrics?

Lundi matin, le roi, la reine et le p’tit prince sont venus chez moi pour me serrer la pince.

Monday morning, the king, the queen and the little prince came to my house to shake my hand.

A translation of the word pince is of course claw,

It is a French song, which yours truly suspected somewhat. What I was totally unaware of was that the original version of that song from the second half of the 19th century referred to Emperor Napoléon III, born Charles Louis Napoléon “Monsieur Oui-Oui” Bonaparte, his wife, Empress Eugénie, born Countess María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina “Paca” de Palafox y Kirkpatrick, and their offspring, Imperial Prince Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph “Loulou” Bonaparte. Who would have thought?

And here are the original lyrics:

Lundi matin, l’empereur, sa femme et le p’tit prince sont venus chez moi pour me serrer la pince.

Monday morning, the emperor, his wife and the little prince came to my house to shake my hand.

And yes, the song is known by more than one title: Lundi matin, Le roi, la reine et le petit prince, Le petit prince and L’empereur, sa femme et le petit prince.

If yours truly may be permitted to paraphrase a good friend, I wonder how many small / tiny anglophone Canadians learned how to say the days of the week in French by singing Lundi matin. (Hello, EP!) And profuse apologies if that song gets stuck in your noggin for the rest of the day. Hi, hi, hi. Sorry.

Again, profuse apologies, I digress a tad too much. Let us therefore get back to Sergeant Electro’s origin story.

The robot was remotely operated by radio signals sent from a control box operated by a specially trained individual which could be up to 23 or so metres (75 feet) away from his charge. That operator lent his voice to the robot through loudspeakers located in the latter’s head, body and epaulettes. Said operators heard various questions addressed to the robot via an unknown number of strategically located microphones. I know, I know. Yours truly does not understand any more than you why it was thought that loudspeakers in the epaulettes were a good idea.

The radio set placed in the robot’s chest came from a mothballed RCAF bomber, possibly an Avro Lancaster – another type of aircraft present in the absolutely fabulous collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

As you may well imagine, the carefully chosen operators which succeeded each other over time were asked / told to speak in a monotone / robotic voice. Said operators tended to be relatively young men who had recently completed their training at No. 1 Radar and Communications School – and thus still remembered the technical information instilled therein.

Whether or not the robot could strike up a conversation in both English and French in 1957 was unclear. It certainly did so during part / much / most of its military career.

Incidentally, the official monthly magazine of the RCAF, The Roundel (1948-1965), did not seem to have a francophone counterpart, and neither did the Royal Canadian Navy’s official monthly magazine, The Crowsnest (1948-1965). The Canadian Army Journal / Le Journal de l’Armée Canadienne (1947-65), on the other hand, was available in both English and French. You do know of course that the Official Languages Act came into force in September 1969, more than a century after the creation of Canada, but I digress.

Before I forget, the Canadian Army was the service with the largest number of francophones. It was also the service in which it was (a tad?) easier for them to carve out a place.

Yours truly does not know precisely when our robot was (officially?) christened Sergeant Electro. This being said (typed?), said christening took place no later than September 1957. The first name frequently associated with that robotic non commissioned officer, namely Bob, may have been chosen at that time – or not.

In any event, Sergeant Electro made its first public appearance in Toronto, Ontario, at the Canadian National Exhibition, in late August and early September of 1957. And here is proof of that assertion.

A young Joseph Agostino shaking the hand of Sergeant Bob Electro at the Royal Canadian Air Force’s booth of the 1957 edition of the Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Ontario. Anon., “Il ne peut parader.” Le Droit, 7 September 1957, 3.

Can you by any chance identify the aircraft portrayed on the wall behind the good sergeant and his young friend, Joseph Agostino? The very first Canadair CP-107 Argus maritime patrol aircraft, you say (type?)? Very good, my wing nutty reading friend. And yes, you are again quite correct. The jaw dropping Canada Aviation and Space Museum indeed has an Argus in its collection.

Would you believe that Sergeant Electro apparently appeared on television in August of September 1957? I kid you not. It was seemingly interviewed live, presumably in Toronto, on a Sunday afternoon, quite possibly by none other than David Cunningham “Dave” Garroway, the very popular host of the very popular weekly American documentary series Wide Wide World, the very first international (United States, Mexico and Canada) television show in North America.

Mind you, the good sergeant might have been interviewed by Garroway during a broadcast of the very popular American daily news and talk television show Today, the very first daily news and talk television show on planet Earth. Yes, that Today show. Pretty good, eh?

Sergeant Electro took part in the 1960 edition of the Canadian National Exhibition. Indeed, it may have present in 1958 and / or 1959, and in 1961 and / or 1962. The latter contribution was uncertain, however, as the good sergeant was put in storage in 1962. You see, its electronics had become obsolescent, if not obsolete. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Fear not, however, my reading friend. Some RCAF muckymuck or other suggested that sergeant Electro could become a “public relations gimmick.” Would you believe that it became quite popular in that new guise?

Indeed, would you believe that at least 9 Canadian daily newspapers in at least 4 provinces published in early 1963 the photograph you saw at the beginning this article? Oddly enough, the good sergeant was identified as Ron, Rob and Bob Electro.

You will of course have noticed that the head the good sergeant’s had on its shoulders in 1963 differed from the one which had beautified its torso in 1957.

One of the venues Sergeant Electro visited more than once during its career was the Exposition provinciale de Québec, an annual agricultural and commercial fair held in Québec, Québec. In August and September 1968, for example, the good sergeant seemingly shared the limelight with a Vertol CH-113 Labrador search and rescue helicopter and a Northrop / Canadair CF-116 supersonic fighter bomber – two types of flying machines operated by the recently (1968) unified Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) found in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The term seemingly found in the previous paragraph may be appropriate indeed given that Le Soleil, the main francophone daily of Québec, the city and not the province, stated in August 1971 that Sergeant Electro would be present at Expo-Québec, as the Exposition provinciale de Québec was known by then, in September 1971, for the very first time. Indeed, it would greet visitors just outside the pavilion of the CAF. That journey to Québec may have been the only one made by the good sergeant in 1971.

Interestingly, the good sergeant was now sporting a new paint scheme and, perhaps, some new electronics. Yours truly has a feeling that he was now painted dark green, like many of the aircraft and vehicles of the CAF – a dark green also used for most of the uniforms worn by members of said armed forces. And here is proof…

Canadian Armed Forces Sergeant Bob Electro, Québec, Québec. Vianney Duchesne, “Tout sera prêt pour l’ouverture d’Expo-Québec demain après-midi.” Le Soleil, 1 September 1971, 17.

Incidentally, the colour of the uniforms in question was seemingly informally / sarcastically referred to by quite a few members of the CAF as garbage bag green.

And yes, the sizeable presence of the CAF and Information Canada, a central federal information agency, a central propaganda agency according to some, founded in April 1970, on April 1st actually, in the provincial capital, was largely political. You may wish to note that what follows is very disturbing.

In October 1970, members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the Montréal-based senior British trade commissioner, James Richard Cross, and the Ministre de l’Immigration and Ministre du Travail et de la Main-d’œuvre of Québec, Pierre Laporte. The latter was killed under circumstances no one really knows and by a member of the FLQ no one ever identified.

The October Crisis, as these events became known, saw the Canadian Prime Minister of the time invoke the 1914 War Measures Act. That action, unprecedented in peacetime, led to the arrests of almost 500 Quebecers who had not taken part in the kidnappings, virtually all francophones and sovereigntists, in other words individuals who favoured the creation of an independent country of Québec. All but 35 or so were released without ever being charged and without so much as an apology, and this despite the fact that some of them had spent up to 3 months in jail. The 35 or so individuals charged were eventually acquitted.

According to some, elements within the federal government had acted in that manner to discredit the Québec sovereignist movement and, more specifically, the Parti québécois, founded in October 1968. Let us not forget that the very young sovereigntist party had obtained 23 % of the votes, a result which had surprised / frightened many people in Québec and Ottawa, but only 7 of the 108 seats in the Assemblée nationale, during the April 1970 election. What do you think?

In any event, given the atmosphere in Québec, both the city and the province, in 1971, the federal government seemingly thought that a sizeable presence at Expo-Québec was appropriate.

Sergeant Electro’s presence at the 1974 edition of Expo-Québec did not go unnoticed. According to a journalist of the sovereigntist daily Le Jour of Ville Saint-Laurent, Québec, a stone’s throw from Montréal, “We were able, better than ever, to fully appreciate the totally stupid show of Sergeant Electro, presented by the Canadian (idiotic) Armed Forces.” Ow…

Mind you, Expo-Quétaine itself, to use the words of the daily, in English Expo-Kitsch, did not escape criticism from Le Jour: “It has been going on 63 years and the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

And yes, the preceding quotes were all translations. You are welcome.

Incidentally, the Parti Québécois won 30 % of the votes but only 6 of the 110 seats in the Assemblée nationale in the October 1973 election. It won 41 % of the votes and 71 of the 110 seats in the November 1976 election. Given such results, one has to wonder if the electoral system in Québec, and in the rest of Canada for that matter, is not rather unfair, if not, dare one say, undemocratic, but I digress.

Sergeant Electro’s regular operator with one of the six female reservists from the Québec region who provided its voice during the 1974 edition of Expo-Québec, Québec, Québec. Anon., “Le sergent Electro, être du XXIe siècle.” Le Soleil, 7 September 1974, 9.

During its stay at the 1974 edition of Expo-Québec, the voice of Sergeant Electro was provided by a team of six female reservists from the Québec region. The robot’s regular operator controlled its movements as usual.

The female voice of the robot seemingly led one or more people to ask questions about its, err, sex life. The answer or answers given by the good sergeant may, I repeat may, have mentioned a lack of programming in such matter.

Some (young?) Québec residents seemed to think that the female person they were talking to was actually inside the robot.

By then, the good sergeant sported a spruced up head, its third, but who was counting, as well as a dashing beret. Said new head was no longer painted dark green. Nay. It may well have been white. The robot also had a more powerful voice. And here is proof of the changes in question…

A somewhat nervous Andrea Potter is touching the face of Sergeant Electro under the benevolent gaze of the robot’s operator, Canadian Armed Forces Sergeant Thomas “Tom” Payette, Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Ontario. Anon., “Sergeant Electro.” The Ottawa Journal, 22 August 1972, 27.

Presumably in answer to a request made by a photographer, Canadian Armed Forces Private Janice Pankiw peered at the inner workings of Sergeant Electro, Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Ontario. Anon., “Carry on, sergeant!” Edmonton Journal, 29 August 1972, 36.

A brief digression if I may. Carry On Sergeant was the 1958 British comedy motion picture which gave birth to a series of 31 slightly bawdy / naughty British movies premiered between 1958 and 1992.

And yes, 11 additional movie projects were abandoned along the way. One of these was Carry On Flying, a 1962 project detailing the trials and tribulations of a group of recruits of the British air force, the Royal Air Force. Proposed in 1961 and again in 1962, Carry On Spaceman would have poked fun at the Soviet-American space race by putting on the big screen a trio of bungling British astronauts.

This being said (typed?), many motion pictures projects which poked fun at the conquest of space more or less gently materialised during the decade which followed the launch of the world’s first artificial satellite, the Soviet Sputnik 1, in October 1957:

À pied, à cheval et en spoutnik! (1958, France),

Totò nella Luna (1958, Italy),

Rehla ilal Kamar (1959, Egypt),

Have Rocket, Will Travel (1959, United States),

Man in the Moon (1960, United Kingdom),

Conquistador de la Luna (1960, Mexico),

Moon Pilot (1962, United States),

Muž z prvního století (1962, Czechoslovakia),

The Road to Hong Kong (1962, United Kingdom),

The Three Stooges in Orbit (1962, United States),

The Mouse on the Moon (1963, United Kingdom),

Sergeant Deadhead (1965, United States),

002 Operazione Luna (1965, Italy),

Way... Way Out (1966, United States), and

The Reluctant Astronaut (1967, United States).

End of digression.

Oh, and yes, À pied, à cheval et en spoutnik! was at the heart of a September 2018 issue of our formidable blog / bulletin / thingee.

Oddly enough, Sergeant Electro may, I repeat may, have journeyed to Western Canada for the first time in 1970, when he conversed with some of the people who visited the Pacific National Exhibition, in Vancouver. It attended the 1972 edition of the Abbotsford International Airshow, held in… Abbotsford, British Columbia.

Over the years, Sergeant Electro visited a number of young children in hospitals. Its operators remembered such moments for the rest of their lives.

An officially-sponsored robot officially took over from Sergeant Electro at a ceremony held at Canadian Forces Base Trenton, near… Trenton, Ontario, in June 1983. Sergeant Servo was somewhat similar in appearance to the world famous and very huggable R2-D2. It officially took over the public relation functions of its predecessor in August. And here they are, together, the old and new…

Sergeant Electro and Sergeant Servo exchanging a few private thoughts as the former goes into retirement, after 26 years of service, Canadian Forces Base Trenton, Trenton, Ontario. Anon., “No gold watch for Mr. Roboto?” The Whig-Standard, 28 June 1983, 1.

You will again have noted that Sergeant Electro sported a new head, its fourth. That robot truly kept changing its mind, and… Sorry.

Yours truly cannot say when that noggin replaced the good sergeant’s third head. I also cannot say if the uniform jacket was donned on a regular basis during the final years / months / weeks / days of its career.

And yes, the forage cap on Sergeant Servo’s head is sort of cute. Incidentally, said head could be replaced by a projection unit used to show, among other things, recruitment videos, and…

Yes, yes, my cinephile reading friend, yours truly remembers the scene in the 1977 blockbuster movie Star Wars / Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope in which Luke Skywalker discovered a holographic recording of princess Leia Organa requesting help from Obi-Wan “Old Ben” Kenobi while cleaning R2-D2.

And if you think that Sergeant Servo’s projection unit was not inspired by that scene, there is a bridge I would very much like to sell you.

To answer the question which popped into your noggin, my brainy reading friend, the reference in the photograph caption above, about the 1983 (!) song Mr. Roboto by the American rock band Styx, played no part in my decision to adapt two of its lines for use in the title of the present article of our gob smashing blog / bulletin / thingee. Yours truly had come up with that idea well before I came across the photograph.

Sergeant Electro was donated to the Military Communications and Electronics Museum, a military museal institution on the site of Canadian Forces Base Kingston, in… Kingston, Ontario, in 1989.

This being said (typed?), its transfer to the museum had been mentioned in the press as early as June 1983. Yours truly cannot say why the donation seemingly took so long to finalise. Anyway, let us proceed toward the conclusion of this article.

From the looks of it, Sergeant Electro was on display at the Military Communications and Electronics Museum for some time in the mid 1990s.

Several attempts were launched in the early 2000s by museum staff and volunteers to repair / rebuild the robot but these efforts came to naught. As well as the asbestos safety hazard issue, the biggest obstacle was the unavailability of the parts necessary to repair / rebuild it.

Sergeant Bob Electro is currently stored at the Military Communications and Electronics Museum.

The author of these lines wishes to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

A potentially dumb idea if I may. Might it be safe to display Sergeant Electro, in a sealed display case of course, in the Cold War exhibition area of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum? Just askin’.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)