The art of the deal in rural Ontario; or, The unhappy tale of the Dresden chondrite

And yes, my reading friend, the topic we will explore in this week’s issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee is astronomical in nature. To paraphrase the lead singer of the American new wave band Talking Heads, in its 1981 hit Once in a lifetime, you may ask yourself why this is so. Well, one could argue that astronomy falls within the mandate of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario. I am not part of this hypothetical “one” – of course.

At least not officially.

So, let’s talk about space and the countless meteoroids, meteors and meteorites found therein, and… Let me guess, some illumination would be required to differentiate these 3 types of celestial bodies, would it not? The blank look on your face was a bit of a giveaway, you know. All right, let’s begin.

To be clear, I was as ignorant as you were / are when I began to write (type?) this issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. And no, there was / is no contest regarding the number of times yours truly can drop this, by now and for a long time, unbearably annoying expression in each and every article of said blog / bulletin / thingee. That’s 3 times so far by the way, but who’s counting? Besides you. Sorry.

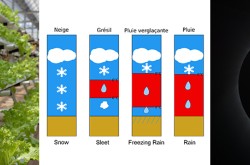

So, let it be known throughout the land that a meteoroid is a rocky or metallic object that travels through space. A meteoroid can be a few millimetres (a fraction of an inch) or a full kilometres (0.62 mile) across. If a meteoroid of a certain size enters the atmosphere of the Earth, friction with molecules of gas present up there heat it up, thus creating a beautiful / frightening streak of light in the sky, in other words a meteor. If a meteoroid is large enough, it will punch its way through said atmosphere and hit the Earth, either in one piece or not. The part(s) of the meteoroid that hit the Earth are / is called a meteorite.

If a meteor is more than twice as bright as the Moon, it becomes known as a bolide. In turn, a superbolide can be brighter than the Sun.

Shortly before 9 PM, as dusk fell, on 11 July 1939, an awe inspiring fireball streaked across the sky of southwestern Ontario. Said fireball, the largest seen in the region in living memory, lit up the sky as if it was midday. Countless thousands of people in that province, from Windsor in the west to Toronto in the east, as well as in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, saw it. Incredibly, a few people in Lethbridge, Alberta, claimed they had seen it too.

What was this thing, wondered the housewife resting after a hard day’s work or the traveling salesman who had parked his automobile by the side of the road? A rocket carrying invaders from China? A bizarre form of lightning? A belated 4 July firework rocket? A forest fire? A burning airplane about to crash? A building in fire? Or something else altogether, like the end of the world? Local police stations and newspapers were soon swamped with calls from concerned citizens. There was fear, if not panic, in certain quarters, it was said. These were troubled times, you see.

The army, or Heer, of National Socialist Germany entered Austria in March 1938 without having to fire a shot. The country’s monstrous leader, Adolf Hitler, then announced the union of his native country with his adoptive country. In July and August 1938, Japanese and Soviet troops fought along the border of Manchukuo, a puppet state created by Japan in northern China in the footsteps of its invasion of that country in July 1937. While the fighting along the border of Manchukuo ceased soon enough, the Sino-Japanese War raged until the unconditional surrender of Japan, at the end of the Second World War, made official in early September 1945.

In September 1938, as Europe held its breath, waiting to see if war would erupt, Hitler, Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini, the buffoonish dictator of Fascist Italy, and the frightened French and British prime ministers, Édouard Daladier and Arthur Neville Chamberlain, negotiated the (in)famous Munich accords, in Munich, Germany. The Czech government, the party most affected by this stab in the back, was not even invited to take part in these “negotiations.” Within days, Germany occupied the border region of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, the last democratic country in that region of Europe. Poland and Hungary took advantage of the situation to grab some pieces of the country as well, in October and November 1938. Slovakia proclaimed its independence in March 1939. This territory, along with Bohemia and Moravia, was soon occupied by Germany. The annexation of Ruthenia by Hungary, in March 1939, completed the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia.

In March as well, the monstrous civil war launched in July 1936 by senior Spanish military officers ended with the victory of Francisco Franco y Bahamonde’s Nationalist forces, a triumph made possible by the massive support of Germany and Italy. Only the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), another evil dictatorship, had agreed to openly support the democratically elected government of Spain. In April, Italy annexed Albania, and Germany terminated the 1935 Anglo-German naval agreement that limited the size of its navy, the Kriegsmarine. The following month, Germany and Italy signed a military alliance. As we both know, the Second World War began in September 1939.

In July 1939, many people around the globe thus feared that another major conflict was about to tear apart Europe.

Indeed, the fear bordering in panic felt by many explained why many people, but not as much as was once thought, freaked out in late October 1938 when a brilliant young American by the name of George Orson Welles broadcasted one of the most amazing and scariest Halloween shows ever, with the help of his Mercury Theater team, namely the radio broadcast of a modernised version of British author Herbert George Wells’ 1898 masterful scientific romance, arguably his most famous work, The War of the Worlds. The aforementioned freaked out people actually believed that a Martian invasion was underway.

And yes, Wells, with one E, was mentioned in November 2018, December 2018 and June 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. In turn, the 1953 film version of his novel was mentioned in a November 2018 issue of that same blog / bulletin / thingee. But back to our story.

Our meteor was seen to undergo 3 explosions before the main fragment, a 40 or so kilogramme (88 or so pounds) meteorite, buried itself in a sugar beet field owned by African Canadian farmer Daniel Alvy “Dan” Solomon, in Chatham county, 10 or so kilometres (6 or so miles) southwest of Dresden, a small town in south-western Ontario, not too far from the Canada-United States border.

It should be noted that, back in 1939, a preliminary report written by 2 University of Western Ontario (UWO) members of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada stated that up to 7 explosions had taken place over Ontario. The first one sent a fragment into Georgian Bay, in Lake Huron, near a yacht and its owner. The second one sent a fragment into Lake Huron, near Listowel, 15 or so metres (50 or so feet) from the shore. The third one sent a fragment between Saint Marys and Stratford, not too far from a witness. The fourth one sent a large fragment near Park Hill. As it turned out, this particular fragment seemingly proved to be a piece of slag, but back to our story. Yes, my reading friend, the preliminary report was inaccurate. And yes, UWO was / is in London, Ontario.

According to at least one July 1939 newspaper, 5 farmers besides Solomon came across small meteorite fragments in their fields. Bruce Cumming and his family found one that may have weighed 500 or so grammes (1 or so pound) on his sugar beet farm, 100 or so metres (330 or so feet) from their house, on 11 July, thanks to their dog Shep. Henry L. Lozon, on the other hand, found a fragment weighing more than 2 kilogramme (about 5 pounds) on his land, on 12 July. A.V. Scott found a fragment of unknown size at an unknown time. An unknown individual found a fragment of unknown size at an equally unknown time. George Highgate was said to have found one such fragment of unknown size at an equally unknown time. According to a contemporary newspaper article, the 5 farmers wanted to sell their fragments and were awaiting offers.

An 8 or so year old boy by the name of Murray McKim found a 150 or so grammes (about 5 ounces) fragment not too far from his parents’ home, near the Solomon farm. This fragment found on 11 July remained unknown to science until 2003.

As well, Clarence Browning of Dresden found a fragment in the garden behind his home on the evening of 11 July.

Other fragments may have been picked up in 1939 or later, by various individuals who chose to keep their mouth shut. If truth be told, there may well be fragments of the Dresden meteorite left in the ground, or in one or more farmer’s basement / attic, but let’s move on.

A startling / puzzling / disturbing conclusion one has to make after perusing the testimonies of the people who saw the fireball is that no 2 of them seemingly experienced the same thing. At the risk of sounding condescending, one could argue that memory is a very malleable and fallible faculty. Speaking about other events altogether, one could even argue that it is possible to remember things that never really happened, but I digress. Err, where were we? I forget.

The Dresden meteor was described as making a sizzling sound or a loud, thunderous rumbly one. Depending on the location of the observers, it moved toward the north, or south, or from some other direction on the compass. A way out of this dilemma would be to suggest, like an unnamed expert from UWO, in all likelihood Harold Reynolds Kingston, the head of the Department of Pure and Applied Mathematics and an astronomy enthusiast, did in July 1939, that the Dresden meteor fell practically straight down. A 2006 article suggested that the Dresden meteor probably followed a northeast to southwest trajectory.

Let us now dig into, no pun intended, all right, all right, pun very much intended, the story of the main fragment of the Dresden meteor – the 4th largest known meteorite from Canada and the 2nd largest one from Ontario. What was / is the largest known meteorite from Canada and Ontario, you ask, my curious reading friend? Well, that would be the Madoc meteorite, an iron meteorite, or siderite, found in 1854, near Madoc, Canada, the pre-1867 united province and not the post-1867 Dominion of course. And yes, my observant reading friend, Madoc is now in Ontario. This meteorite tipped / tips the scale at 169 or so kilogrammes (373 or so pounds). No one knows when it hit our world – or vice versa.

Yours truly would very much to talk (type?) about meteorites and their craters. Did you know, for example, that Swedish American, later Swedish Canadian geophysicist Hans Torkel Fredrik Lundberg went to Arizona to see if he could detect the remains of a meteorite underneath Crater Mound, a spectacular feature known today as Meteor Crater? I shall refrain from talking (typing?) about meteorites and their craters, however. You, my reading friend, have places to see and things to do, after all. Changing diapers on the side of the road for example. Hello, EG! And yes, Lundberg was mentioned in July 2017 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Before I forget, did you know that a sizeable meteorite, an iron meteorite to be more precise, was on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum between May and September 2018? This space visitor, the Knowles meteorite, found near Knowles, Oklahoma, in 1903, was one of the many fascinating items included in the American Museum of Natural History traveling exhibition Beyond Planet Earth: The Future of Space Exploration. And yes, you should visit that museum more often, and… No, not the American one, although it’s probably fascinating as well. You have never been to the august institution that is the Canada Aviation and Space Museum? Seriously? Wow. Let us move on, and... Never? Seriously? Go! Not now of course, you have some reading to do. So, back to our story.

Hazel Bell Richardson Solomon was weeding her garden when the meteor came into view. It quickly grew larger and made a loud, terrifying noise as it crashed in a field, 200 or so metres (650 or so feet) from her house. She rushed inside with her 4 frightened children. Her spouse, the aforementioned “Dan” Solomon, returned from Dresden a few minutes later, in his old automobile. His spouse asked him to wait until the following morning before having a look at the crash site.

Yours truly is of the opinion that the green and yellow smoke emanating from said crash site existed only in the imagination of a journalist.

Solomon was born in Chatham, Ontario, not too far from Dresden, in October 1896. Of military age during the second half of the First World War, he was drafted in June 1918 but did not see combat before the signature of the Armistice, in November.

Even though said Armistice was signed more than a century ago, the impact of the First World War has yet to run its course around the globe. In Québec, the second most populated province of Canada and stronghold of the Dominion’s French speaking minority, the conflict left an especially bitter taste.

You see, my reading friend, in August 1917, in Ottawa, the House of Commons voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Military Service Act. This imposition of conscription for service overseas by the federal government, then led by Sir Robert Laird Borden, angered numerous recent immigrants in western Canada, many people in rural Ontario and the great majority of French speaking Quebecers. Unlike many of their English speaking compatriots, who were born in the United Kingdom and / or still had close relatives there, the latter’s attachment was first and foremost to their home and native land in North America. Indeed, to the average French speaking Quebecer, France was an unknown if not foreign country her or his ancestors had left at least a century and a half before. The United Kingdom and the British Empire counted for even less in her / his heart.

Seeing Canada involved into a war on the other side of the Atlantic was bad enough, but being ordered out of one’s home to face death overseas was just beyond the pale. The passage of the Wartime Elections Act, in September 1917, that enfranchised many potential supporters of conscription and disenfranchised many potential opponents of the measure, in preparation for a federal election, only added insult to injury. In October, Borden formed a union government with the help of a few pro-conscription members of the official opposition who chose the lure of power over loyalty to their leader, former Prime Minister Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier and, quite possibly, their own constituents. All of this manoeuvring, combined with widespread government-sponsored fraud, some intimidation and the post electoral redistribution of the military vote in several ridings won by the official opposition, pretty much guaranteed Borden’s crushing and, dare one say, borderline illegal victory in the federal election held in December.

Oddly enough, this tainted and, dare one say once again, borderline illegal victory came 14 years to the day after the first controlled and sustained flights of a powered airplane, made by Orville and Wilbur Wright, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. And yes, these aviation pioneers known around the globe were mentioned a few times in our blog / bulletin / thingee since August 2018

In fairness, young English speaking Canadians proved almost as eager as their French speaking counterparts to request exemptions from overseas service, at least until the federal government all but eliminated these, in April 1918, soon after the launch of a major offensive by the German armed forces. It was in Québec, Québec, however, that tensions reached their peak, with the confirmed deaths of 4 unarmed and seemingly uninvolved French speaking individuals, at the hand of English speaking soldiers from outside the province, on 1 April, on Easter weekend. As many as 70 people may have been injured. Not exactly peace on Earth and goodwill towards mankind, I guess. Sorry.

Overtly pacified, most French speaking Quebecers remained profoundly hostile to Borden, his political party and / or the Canadian armed forces for many years after the signing of the Armistice. Indeed, draft dodgers were often able to count on widespread sympathy in 1917-18, especially in the countryside, while the people who came looking for them found mainly sullen silence. Ancestors of mine may well have been among those sullen silent people. Dare I tip my hat to them? But back to our story.

What is it I hear? The impact of the First World War was / is not that great? As was said (typed?) above, the beginning of the Second World War, in September 1939, was preceded by a series of increasingly more serious crises. Although away from areas of tension, the federal / Canadian government realised that the risk of war was increasing. In 1936, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie “Rex” King created a Cabinet Defence Committee which would coordinate and define the policies of his government. All the big guns of the Cabinet were part of it: King; Charles Avery Dunning, Minister of Finance; Ernest Lapointe, Minister of Justice and right hand man of the Prime Minister in Québec; and Ian Alistair Mackenzie, Minister of National Defence. The creation of this committee prefigured the coordinating and directing role of the federal government in matters of economic planning and war production.

At the first meeting, ministers took notice of reports prepared by the Canadian armed forces. The news was bad and the deficiencies, numerous. King and his ministers therefore decided to launch a rearmament program. The financial resources of the country being too limited, the federal government could not afford to buy all the equipment recommended by the Department of National Defence. King thus began to take an increasing interest in the potential importance of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) for the defence of the country.

Without being decisive, a meeting with British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin in October 1936 played a significant role in what followed. The latter suggested that King thought especially in terms of military aviation. Even though Canada was one of the least vulnerable countries, an air force would be most useful in case of attack. Baldwin did not seem to believe that a navy or army were worth spending a lot of money on.

With these military arguments went the fact that unlike the Canadian Army and the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), the RCAF did not awake bad memories, such as the riots against conscription of the spring of 1918 and the difficulties surrounding the creation of the RCN in 1910. Let’s not forget that the official opposition then seemed to favour the donation of a large sum of money to the United Kingdom so that it could strengthen the Royal Navy.

In any event, even before the end of 1936, King decided that the RCAF would be Canada’s first line of defence. In the event of danger, its units could indeed concentrate very quickly and ensure the territory’s protection in collaboration with the RCN and the Canadian Army. As far as King was concerned, this policy also put an end to the idea of a Canadian Army expeditionary force, closely linked to the idea of conscription and the potential danger that this question posed to the unity of the country, but back to our story.

When Solomon walked to his field to figure out what had taken place the day before, he found a hole measuring 30 x 45 centimetres (12 x 18 inches) surrounded by piled up earth. The shock of the impact had been such that chunks of earth were thrown more than 12 metres (40 feet) away. Solomon began to dig into the clay as his children looked on. At a depth of about 2 metres (6.5 feet), he saw the top of the object which had frightened his family the previous day. Solomon’s children were fascinated by this apparition, as was the crowd of neighbours who had come to the scene. Among them was Charles “Charlie / Chuck” Ross, the young editor of a recently founded local weekly newspaper, The Dresden News.

Solomon hooked a chain around the meteorite with the help of Ross. In turn, they needed the help of several men to get the meteorite out of the hole. Using crowbars, 2 or more men chopped off at least 2 relatively large pieces off the interplanetary visitor. Morley McKay, a prominent Dresden resident and owner of Kay’s Café, a popular restaurant, seemingly took one that weighed approximately 700 grammes (1.5 pound), for example.

Grateful for the help provided by Ross, Solomon allowed him to take the meteorite to the office of The Dresden News where it was weighed, cleaned and put on display in the front window. Ross’ sister, Beth Ross, did at least part of the cleaning. The meteorite was scheduled to stay there for 2 weeks. One has to wonder if Solomon heard that Ross soon claimed that he himself had more or less dug the meteorite out of its clay prison.

The discovery of this sizeable meteorite fragment came as a bit of surprise to some / many / most observers who thought that nothing would be found because the meteor had disintegrated before hitting the ground or had gone down in Lake Erie or Lake Huron.

Solomon was soon contacted by a former dentist then living in Chatham who was involved in oil and gas prospecting. Born in Bothwell, Ontario, in 1874, Luke Egerton Smith obtained a degree in dentistry from the University of Toronto in 1899. He practiced in several Ontario towns and cities (Chatham, Hamilton, London and Oakville) before retiring, around 1925. Smith was also an inventor who developed several types of machines. One of these, a jam filling machine, was still in use in the late 1940s or early 1950s, but back to our story.

Smith saw the meteorite as it was being cleaned. He was suitable impressed and “thought that an oil man should not miss a chance to get that close to heaven.” Smith quickly paid Solomon a visit. He may have offered $ 4 for the meteorite because someone had already put in a $ 3 bid. Smith and a farmer friend also interested in prospecting, Marshall McFadden, pestered Solomon, a slight, very gentle and soft-spoken man, to such an extent that he finally gave in, on 12 or 13 July. Quite possibly at the request of Ross, Smith agreed to leave the meteorite in the front window of the office of The Dresden News for 1 week, if not 2.

Anxious as he was to be rid of the meteorite, possibly to prevent his crops from being trampled by gawkers eager to see the hole in his property, Solomon initially thought he had made a good deal. Incidentally, restaurant owners in Dresden also made good sales. The small town was abuzz with activity. Quite a few journalists and hundreds of gawkers had invaded its streets.

Within hours, Solomon realised he had been taken advantage of, a conclusion reached by many other people in Dresden, Chatham and beyond. Indeed, Clarence Augustus Chant, director emeritus of the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, near Toronto, a gentleman mentioned in an April 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, stated on 13 July that the Dresden meteorite, given its condition and size, could fetch $ 200 any day on the open market.

A journalist who pointed this out to Solomon’s spouse that very day noted how distraught she was. He must have been worrying about some problem that his family was having, she thought. Even so, what was he thinking? Solomon and his spouse concluded that they should try to get the meteorite back. On the evening of 13 July, Solomon drove to Smith’s palatial home. His attempt to return the $ 4 in exchange for the meteorite ended in failure. As Smith pointed out to those who questioned his ethics, a deal was a deal.

When talking to journalists around 13 July, Smith (truthfully?) claimed that he did not know why he had bought the meteorite, nor what he would do with it. As several (7?) universities and museums in the United States and Canada, among them UWO and the University of Toronto, not to mention a few private individuals, contacted him with offers of money, he realised that his $ 4 investment could reap him a huge profit. In mid-July, Smith visited the office of The Dresden News, demanded to have his property returned to him, and drove home. Questioned by journalists, he stated he would sleep right beside the meteorite, with a pistol / revolver under his pillow. For a reason or other, Smith loaned the meteorite to a major newspaper, Toronto Daily Star, the day after his visit to the office of The Dresden News. The publicity conscious Toronto daily put the meteorite in a front window of its offices.

Did you know that a photo of the meteorite being cleaned by Ms. Ross made the front page of the 13 July issue of Toronto Daily Star? You did? Oh yes, that very photo was at the top of this article. I knew that. Yes, yes, I did. I think, but back to our story.

As this was taken place, hordes of motorists, many of them American, some from as far away as Ohio, were still showing up at Solomon’s doorstep, asking if they could see the meteorite. Although understandably disappointed to hear it was in Chatham, with Smith, these visitors from afar peered at the ground near the crash site, in the hope of finding a tiny chip or 2. A small number of them struck gold, so to speak. Mind you, Wilfred Solomon, the second oldest child of the family, sold a number of tiny chips, for a few pennies, to passing motorists.

Two UWO emissaries of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Edward Gustav Pleva and Reverend W.G. Cosgrove, made the trip to Dresden on 13 July. Before leaving London, the one in Ontario of course, they stopped at the telegraph office of the Canadian National Railway Company to examine a rock said to be a meteorite fragment, at least according to a journalist and co-founder of London-based Carty News and Publicity Service, quite possibly Arthur Chester Carty, born Arthur Chester Pudney, who often provided stories to Toronto Daily Star. Said fragment contained a fair amount of metal, presumably iron. Pleva and Cosgrove concluded it could well be genuine. The 2 men left for Dresden soon after.

A brief examination of the meteorite, at the office of The Dresden News, convinced them that they were dealing with the real thing, and not some piece of slag. All too often, individuals who thought they had discovered a meteorite fragment they could sell to the highest bidder found out to their dismay that their rock had no value whatsoever. Indeed, a journalist from Toronto Daily Star who contacted the UWO emissaries to get information mentioned that a meteorite fragment analysed in that fair city had proven to be less than genuine.

Soon after, Pleva and Cosgrove drove to the crash site to talk to Solomon and other farmers along the way. They wondered how a meteorite weighing only 40 or so kilogrammes (88 or so pounds) managed to end up more than 2 metres (about 7 feet) underground. As well, the clay at the bottom of the hole did not seem all that compacted.

Pleva and Cosgrove drove back to Dresden a week after their initial journey. A geology professor at UWO, G. Howard Reavely, accompanied them. The terrific trio’s goal was to locate as many meteorite fragments as humanly possible. In the end, this visit resulted in the donation to UWO of the meteorite fragment owned by McKay. His only condition was that said fragment be cut in half. The university was to keep one intact while the other was to be polished on one face and returned to McKay. Reavely, Pleva and Cosgrove were ecstatic, as were their colleagues at UWO and the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

Smith, on the other hand, went ballistic when he heard the news. The meteorite pieces were stolen property, he said, and should be returned to him. From the looks of it, his bluster did not unduly disturb McKay or UWO. This being said (typed?), Smith turned down a $ 200 offer for the meteorite from that very university in early August. The University of Toronto was no luckier. Hoping to reap a much larger sum of money, Smith threatened to cut in 8 pieces the Luke Smith Meteorite, as he was seemingly fond to call this heavenly rock. He would pay to have this name engraved on a polished face of each fragment, with the date of the meteorite’s fall – and the names of the 2 villains who had chopped off the pieces now owned by McKay and UWO.

Smith’s behaviour did not go unnoticed, far from it. If truth be told, he was seriously criticised. An early August editorial published in St. Thomas Times Journal of St. Thomas, Ontario, was especially harsh. Where would the world be had world famous American inventor Thomas Alva Edison and / or equally world famous French scientist Louis Pasteur, an individual if not a gentleman mentioned in an April 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, kept their work secret until handsome piles of money had been given to them? The editorialist went on to day that the little Chatham dentist, a sly dig at Smith perhaps, because the latter was far from little, “while scarcely able to win a place in history with a piece of rock, could at least aid the efforts of astronomers if he would develop a little of the character of these famous men.”

In fairness to Smith, one had / has to point out that Edison was a fiercely competitive businessman while Pasteur was by no means humble, likeable or selfless. Indeed, it looked / looks as if the latter regularly purged his raw experimental data to fit the results he wanted to achieve. Worse still, in at least 2 significant cases, linked to his work on anthrax and rabies, Pasteur lied about his methods, conducted human trials that would be unethical today and appropriated one or more ideas from a rival without influence. And yes, my reading friend, yours truly was / is a bit of an iconoclast.

In any event, Smith, who was seemingly familiar with a well-known 1830 saying by a not well known British travel writer and historian, Alexander William Kinglake (Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never harm me), went on with his life. In early August 1939, for example, he pointed out that “the law of supply and demand [held] good even for meteorites” – a statement that did not make him any more popular. Smith indicated that he had been and was being contacted by several / many Canadian and American museums and universities, the famous Smithsonian Institution among them. None of them had seemingly offered him the sum he wanted for the meteorite, which was between $ 800 and $ 1 000 – a sizeable sum in 1939 given that an average worker in the Canadian manufacturing industry earned approximately $ 975 a year at that time.

Perhaps concerned that the meteorite might leave Canada, and / or annoyed by Smith’s behaviour, E.E. Reid, the managing director of London Life Insurance Company, who happened to be a member of the board of governors of UWO, convinced the board of directors of his employer to provide the university with a sum of $ 700 it would use to buy said meteorite. Smith took the money in October 1939.

Following Reid’s request, the meteorite was displayed at the Hume Cronyn Memorial Observatory, constructed on UWO’s campus thanks to a donation from the estate of London businessman and politician Hume Blake Cronyn and officially dedicated in October 1940. Would you believe, my reading friend, that Cronyn, an individual deeply interested in science, played a role in the birth of the Honorary Advisory Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, today’s National Research Council (NRC)? And yes, NRC was mentioned in several issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee since May 2018. And yes again, Cronyn was the father of respected actor Hume Blake Cronyn, Junior.

One has to wonder if the social context surrounding daily life in Dresden did not play a role in the way Solomon was treated. And yes, yours truly is about to go on a tangent. Again. Please note that this tangent is by no means a cheerful one.

Do you know what the Underground Railroad was / is, my reading friend? No? Let me enlighten you in that regard. Said railroad had no tracks or locomotives. It was a network of safe houses and secret routes set up on American soil, primarily in the early to mid-19th century, to help escaped slaves reach American states or British colonies like Nova Scotia and Canada, where slavery, an abominable institution, did not exist.

One could argue that the Underground Railroad was comparable in concept to the networks set up in European countries occupied by National Socialist Germany during the Second World War to help Allied aviators whose airplanes had been shot down, as well as Jewish refugees, reach neutral countries like Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.

Up to 1861 and the start of the American Civil War, Dresden, Canada, the pre-1867 united province and not the post-1867 Dominion of course, was pretty much the end of the line, a beacon of freedom and hope for the thousands of slaves, up to 30 000 perhaps, who were fleeing the slave holding southern states of the United States. Many of these African Americans settled in the area. Indeed, Josiah Henson, the American abolitionist, author and minister whose life may have inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe’s epoch making novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly, published in 1852, lived his final years near Dresden and was buried there.

As time sped by, life for the African Canadians who lived in and near Dresden did not improve all that much. Indeed, it may well have taken a turn for the worse. Let us be blunt here. Dresden seemingly became one of the most racially segregated municipalities in Canada. A cynic might say, however, that the white citizens of Dresden were simply less hypocritical than a lot of white Canadians, but I digress.

Actually, let me include an example of the attitude of a true Canadian institution toward people of African descent. In early August 1945, while the Second World War, a war fought to preserve freedom and justice in the world, was still raging, Dr. George Dows Cannon and his spouse, Lilian Moseley Cannon, arrived at the Château Frontenac, a magnificent Québec, Québec, hotel which belonged to a Canadian transportation giant, Canadian Pacific Railway Company. They booked a room. As the couple tried to enter the dining room to have a meal, they found their way blocked by an employee who stated that people of colour (Negroes being the term used at the time?) were not allowed in. The following day, Cannon and his spouse were informed that any and all public rooms of the hotel were off limit. The management of the Château Frontenac had insulted the wrong person, not once but twice.

You see, Cannon was a well-known and respected radiologist who happened to be an important member of the African American community of New York City, New York. He sought and seemingly obtained 2 temporary injunctions, in superior court, one per insult, forcing the Château Frontenac to treat him and his spouse like its white visitors – in all likelihood a Québec, if not Canadian first, but let us go back to Dresden.

In the mid-1940s, or probably earlier, the owners of several / many / most stores, restaurants and barber shops in town consistently refused to serve the 300 + African Canadians residents of this small town – and this despite the fact they made up almost 20 % of the population. In the middle of the Second World War, an African Canadian serving in the military found it difficult to buy so much as a cup of coffee in Dresden. Answering a letter to that effect, sent to Justice Minister, and future Prime Minister, Louis Stephen Saint-Laurent, his deputy minister indicated that the federal government could do nothing. Frederick Percy Varcoe all but stated that racial discrimination was not illegal in Canada.

The Dresden Story, a 1954 episode of the television series On the Spot, produced by the National Film Board, a world famous federal institution mentioned in July and November 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, was well worth watching. Sadly enough, it seemingly no longer exists.

An African Canadian veteran of the Second World War who earned a living in Dresden as a carpenter, Hugh Burnett / Burnette, played a crucial role in forcing local businesses to serve customers who were not lily white. This particular struggle, a celebrated civil rights case which began in 1948, came to a close in 1956 when the aforementioned McKay, a potentially violent individual and one of Dresden’s main segregationists, reluctantly agreed to comply with a court decision to that effect. By that time, the Dresden story, and a pretty shameful one it was, was known across Canada, thanks in part to The Dresden Story, to a hard hitting article published in the 1 November 1949 issue of Maclean’s and to the well reported defeat, and a crushing one it was, of a December 1949 referendum on whether or not the town council should have the power to cancel the license of businesses that practised racial and / or religious discrimination.

A sad tangent on Dresden, the German city of Dresden, if I may. The bombing of this beautiful city, in February 1945, when the war in Europe seemed almost over, was / is / will be one of the most controversial episode of the strategic bombing campaign against National Socialist Germany during the Second World War, but back to our story.

Interestingly, the editor of Maclean’s, a well-known and respected Toronto weekly magazine, was an author, popular historian and journalist by the name of Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton. Would you believe that this gentleman was chosen, around 1987-88, to narrate the English version of all the videos on the floor of the brand new building of the National Aviation Museum, today’s Canada Aviation and Space Museum? If I may be permitted to quote a 1962 song by brothers Robert Bernard Sherman and Richard Morton Sherman, it’s small world after all. It’s small, small world.

Incidentally, did you know that this incredibly popular ditty was written in the wake of one of the most dramatic episode of the Cold War? No, not the September 1972 Canada-USSR hockey series, also known as the Summit Series or Super Series. Geez. It’s a small world, say I, was written in the wake of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, and… That does not ring a bell, now does it, my reading friend? Fear not, I shall not pontificate on this highly dramatic episode of the Cold War. You will have to conduct your own research on that question.

Incidentally, while one can understand why the American government did not appreciate the fact that the government of the USSR wanted to install (thermo)nuclear missiles in Cuba, within range of many of its cities, one can also understand that the government of said USSR also did not appreciate the fact that the American government had installed (thermo)nuclear missiles in Turkey, within range of many of its cities. Just sayin’ but I digress. And no, I am not a Soviet / Russian deep cover spy. Really.

By the way, did you know that Pope Ioannes XXIII / John XXIII played a significant if often overlooked role in the resolution of this quasi apocalypse? But back to our topic and to the need for a statement, a serious one if I may.

The struggle to bring down discrimination for reasons of age, disability, ethnicity, gender, language, mobility, sexual orientation, race, religion, etc., continued / continues / will continue. If I may be permitted an important if, sadly enough in 2019, potentially controversial comment in regard to this week’s topic, Black lives matter.

Solomon, the central character of our story, died in 1968. He was 71 years old. Smith, on the other hand, died in November 1950. He was 76 years old.

In 2003, as he began to look for yet unknown fragments of the meteorite, Howard Plotkin met one of Solomon’s granddaughter, Betty Solomon, and her father, Wilfred Solomon. This UWO Department of Philosophy history of science professor soon realised how painful the story of the meteorite was for Solomon’s descendants. He also realised that UWO had never recognised Solomon’s role in the discovery and recovery of the meteorite, by then known as the Dresden chondrite. Plotkin concluded that something should be done about both of his realisations.

Acting in conjunction with the chair of UWO’s Department of Earth Sciences, Wayne Nesbitt, he convinced the university’s administration to invite as many members of Solomon’s family as possible to a dinner, on campus, where their ancestor’s role in the discovery and recovery of the Dresden chondrite would finally be recognised. Said dinner was held in November 2003. Thirty-three members of Solomon’s family, great grandchildren, grandchildren, as well as 3 of his 7 (or 8?) children, among them the aforementioned Wilfred Solomon, were present at the dinner, known as The Dresden (Ontario) Meteorite: A Tribute to Dan Solomon. They saw the main fragment of the meteorite, on display outside the office of the Department of Earth Sciences, and visited said department’s research facilities. The members of Solomon’s family then joined 12 individuals linked to UWO, among them the deans of the faculties of arts and humanities, and of science, for the tribute and dinner.

Plotkin said a few words about Solomon, adding that the meteorite had been an invaluable resource for generations of UWO students and faculty members. Indeed, several UWO professors active in 2003 were heavily involved in the study of meteorites. The Dresden chondrite itself was an essential component of UWO’s recently created Planetary Science Program. Said program still existed in 2019, as a 4 year bachelor’s degree jointly offered by the Departments of Physics and Astronomy, and Earth Sciences.

Plotkin then presented a 57-gramme (2 ounces) fragment of the Dresden chondrite to the Solomon family, which was both surprised and very pleased. You will remember, because yours truly said (typed?) so earlier, that an unknown individual had found a meteorite fragment of unknown size at an equally unknown time. It so happened that a St. Thomas physician and meteorite enthusiast / collector had come across said fragment, or a fragment thereof, at a flea market in / near Grand Bend, Ontario. David Gregory immediately bought it. He contacted Plotkin soon after, and offered to donate the fragment to UWO. Although deeply touched by this offer, the latter suggested that the fragment be donated to the Solomon family. Gregory readily agreed that such a donation would be far more meaningful.

Plotkin surprised the members of the Solomon family a second time by announcing the creation of the Solomon Family Award in Planetary Science, which would grant $ 500 to a high achieving yet financially stretched 2nd year student in the honours specialisation program in planetary science at UWO. This annual award, initially suggested by Nesbitt, was allocated for the first time during the 2005-06 academic year. The Solomon Family Award in Planetary Science still existed as of 2019. It was then worth almost $ 1 300.

Would you believe that the Bell Aerospace Company Division of the American industrial giant Textron Incorporated set up the Bell Aerospace Canada Division of Textron Canada Limited at Grand Bend? Small world, isn’t it? Its hovercraft manufacturing factory opened around January 1971. All of these companies were mentioned in March 2018 and April 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee. On top of that, Textron was mentioned in an August 2018 issue of that same blog / bulletin / thingee.

Now that you know what happened to the meteorite fragment, or a fragment thereof, found by an unknown individual at an equally unknown place and time, would you like to know where the other fragments of the Dresden chondrite can be found? Yes, you do, my reading friend. Even if you don’t, yours truly will tell you anyway. The Cumming fragment was (is?) owned by Plotkin. The McKim fragment was (is?) owned by the grandson of its discoverer, Devon Elliott. The Lozon fragment, on the other hand, can be found in Ottawa, in the National Meteorite Collection of Canada of the Geological Survey of Canada, a component of Natural Resources Canada. Sadly enough, the Scott fragment has seemingly gone missing. The Highgate fragment, on the other hand, may have never existed at all. The Browning fragment and the one the aforementioned Pleva and Cosgrave examined in London, finally, seemingly proved to be pieces of slag.

The whereabouts of either half of the fragment acquired by the equally aforementioned McKay after it was chopped off the main fragment of the Dresden chondrite are unknown.

In March 1943, the aforementioned Reavely donated a fragment chopped off that same main fragment to the Royal Ontario Museum of Toronto. Yet another fragment off that same main fragment may have gone to the David Dunlap Observatory around that time. Its whereabouts are seemingly unknown

Incidentally, the Dresden chondrite left the Hume Cronyn Memorial Observatory in 1970. A plaster cast of this heavenly visitor went on display there around the time the real thing was placed in a glass showcase outside the office of the Department of Geology, today’s Department of Earth Sciences, at UWO. The meteorite and the plaster cast were seemingly still on display in 2019.

I see a hand peering through the ether, waving furiously. Do you have a question, my reading friend? Why didn’t you say (type?) so? Do ask. Why in darnation did / does yours truly refer to our piece of heaven as the Dresden chondrite, you ask? A good question. A rocky / stony type of meteorite, chondrites were / are the most commonly found type of meteorite. This, of course, means that our chondrite did / does not contain a fair amount of metal, presumably iron, which means, as was said (typed?) above, that the meteorite fragment examined in London by Pleva and Cosgrove did not really come from a meteorite. It was, in all likelihood, a piece of slag.

Let us conclude this week’s exercise in pontification with a heartfelt “See ya later” on my part.

I wish to thank all the people who provided information. Any mistake contained in this article is my fault, not theirs.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)